Motor Fine Tuning: the Modulation of Movements

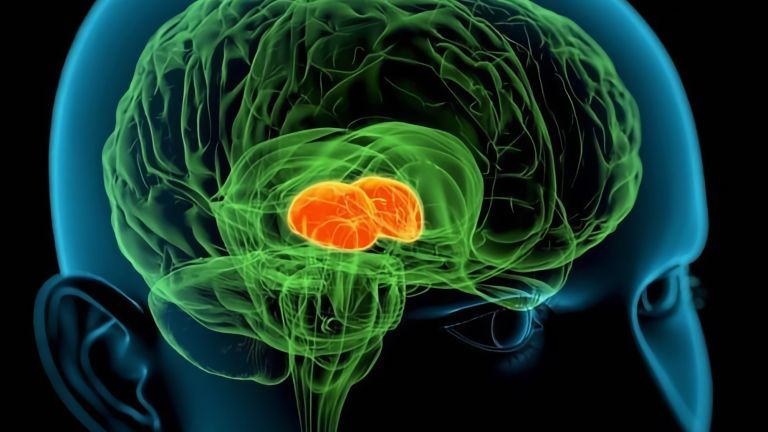

Movements are designed, planned, and sent to the muscles for execution by the motor areas of the cerebral cortex. Two other brain structures are essential for their precise, smooth implementation: the cerebellum and the basal ganglia.

Scientific support: Prof. Dr. Hansjörg Scherberger

Published: 01.12.2025

Difficulty: intermediate

- Although the cerebellum and basal ganglia cannot trigger movements themselves, they are essential for controlling them and for our ability to perform complex movement sequences.

- The cerebellum compares a planned movement with the one currently taking place and makes corrections.

- If the cerebellum is damaged, movements become erratic, jerky, and miss their target.

- The basal ganglia select between undesirable and desirable behavior patterns and movement sequences.

Extend your right arm, pause briefly, and then touch your nose with your right index finger. Can you do it? Even with your eyes closed? Then thank your cerebellum! Because it is only with its support that we can perform this targeted movement precisely and smoothly.

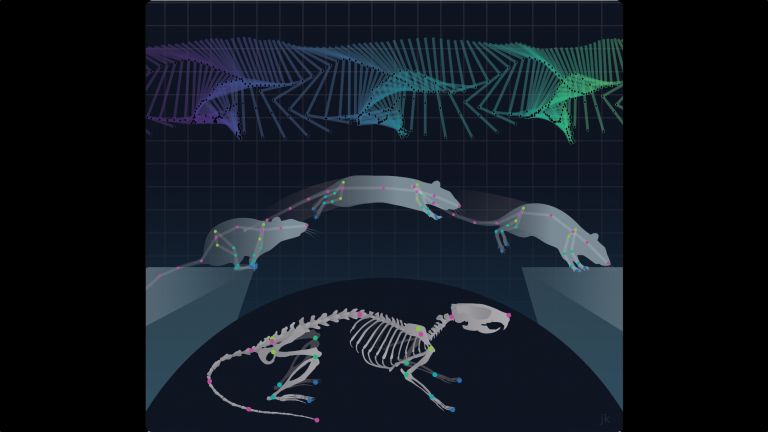

As simple as the finger-nose exercise may seem, it requires a detailed sequence of precisely timed muscle contractions in the shoulder, arm, and hand. Disorders of the cerebellum impair this coordination to such an extent that precise movements become impossible. The associated clinical picture is derived from the Greek word for disorder and is called ataxia.

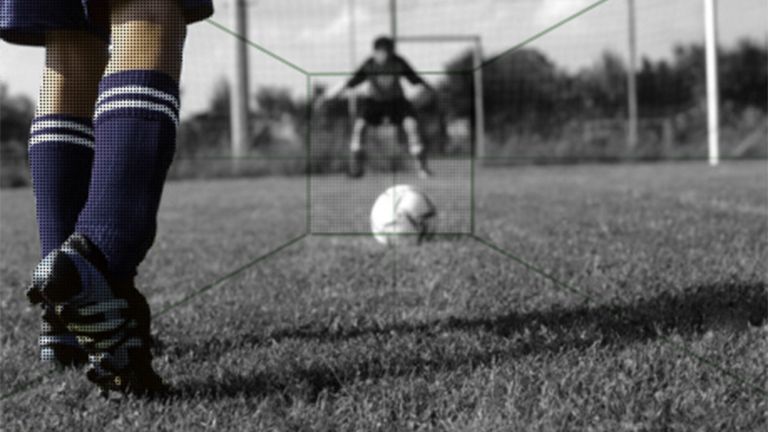

If the cerebellum is damaged, the shoulder, elbow, and wrist are not moved simultaneously to bring the finger to the nose in one movement, but one after the other. The finger trembles back and forth in a zigzag pattern and ends up in the eye or on the cheek because the movements can no longer be measured correctly and overshoot the target. Whether screwing in a light bulb, painting a picture, or playing badminton – without the cerebellum, our complex motor skills would be unthinkable. This is because the cerebellum, constantly monitors all movements to ensure that everything happens as planned by the motor centers in the cerebral cortex, and makes fine corrections – unconsciously, of course. It also ensures that we can maintain our balance. If we suddenly lift one leg, the cerebellum re-coordinates muscle activity so that we do not fall over.

Another structure that is not part of the cerebral cortex and also plays a crucial role in controlling and modulating movements is the basal ganglia, which constantly select between unwanted and desired patterns of action. They help us to perform fine motor movements in a controlled manner, to the appropriate extent and in the correct direction. This allows us, for example, to touch the proverbial raw egg without crushing it.

The cerebellum keeps track of everything

Basal ganglia disorders cause movement disorders related to the strategic planning and initiation of motor actions. The cerebellum intervenes one level lower in the hierarchy of movement control – at the execution stage. With its help, initiated movements are translated into fluid, precise sequences of actions. It is thanks to the cerebellum that we do not stagger around like zombies.

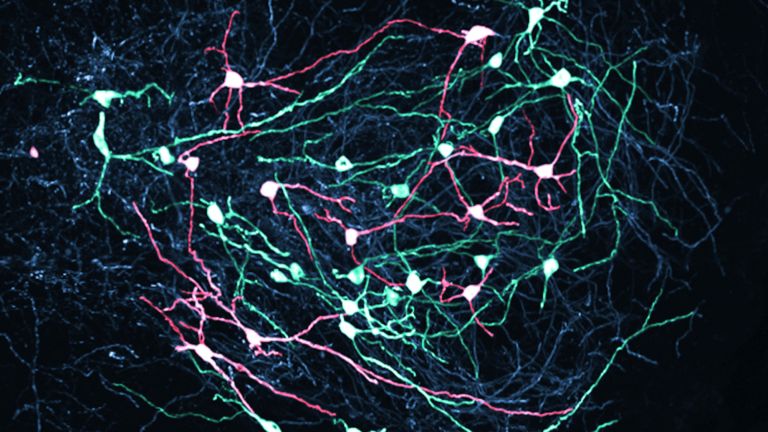

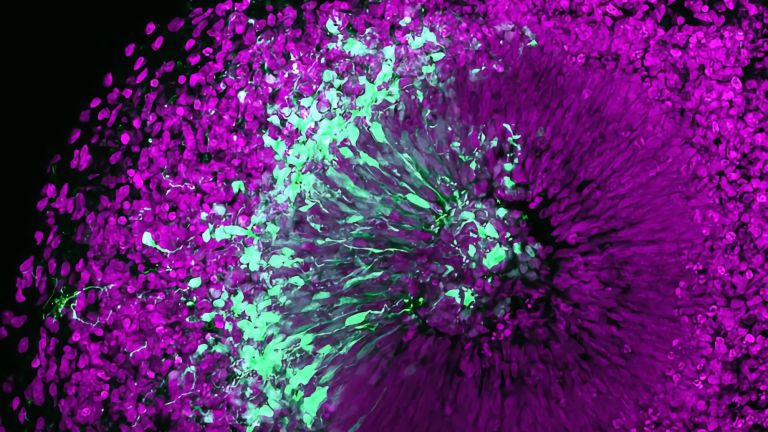

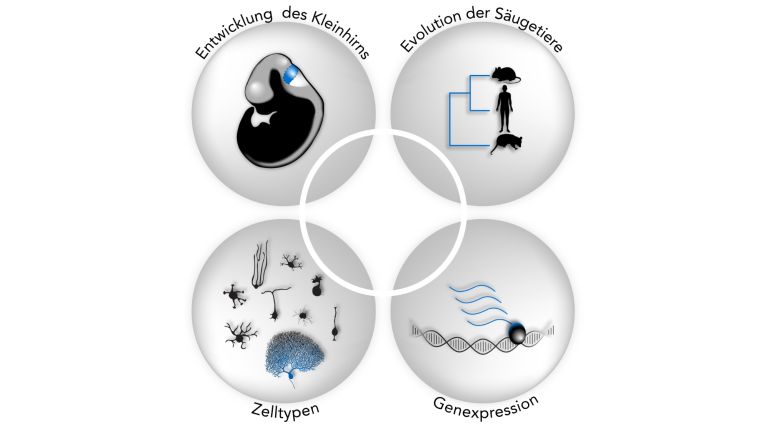

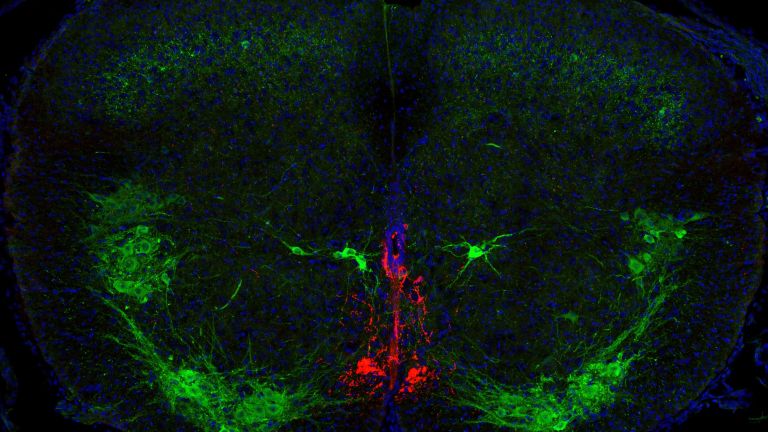

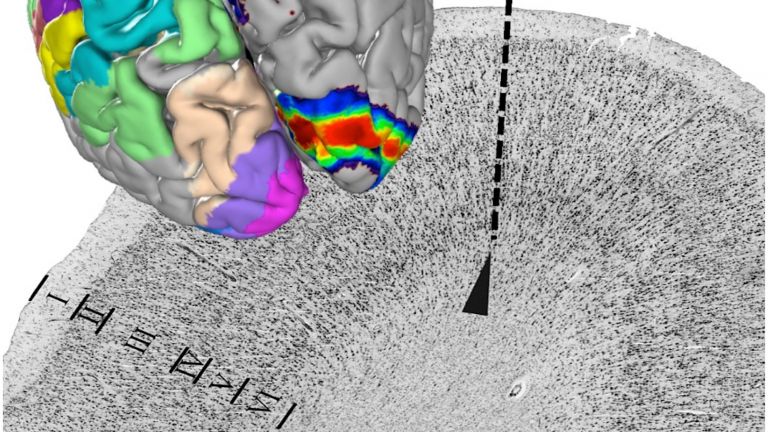

Although the cerebellum accounts for only one-tenth of the mass of the entire brain, it houses over half of its nerve cells. This alone shows how complex its neural connections are. It looks like a modified mini version of the cerebrum and is located in the posterior cranial fossa. When cut open, its structure resembles a tree with many branches: the cerebellum is extremely furrowed, which greatly increases its surface area.

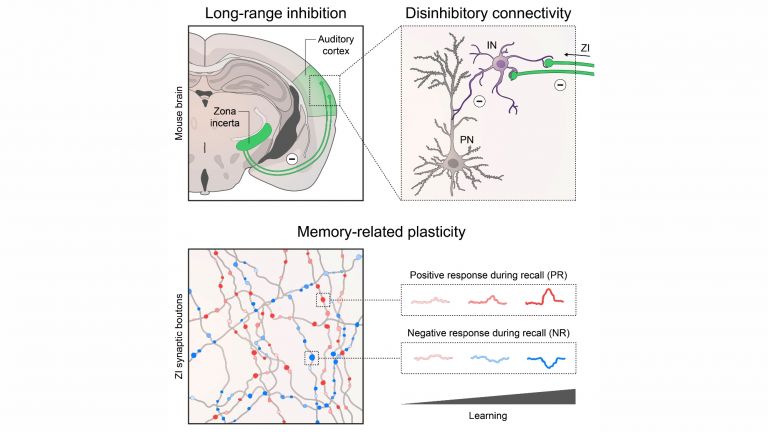

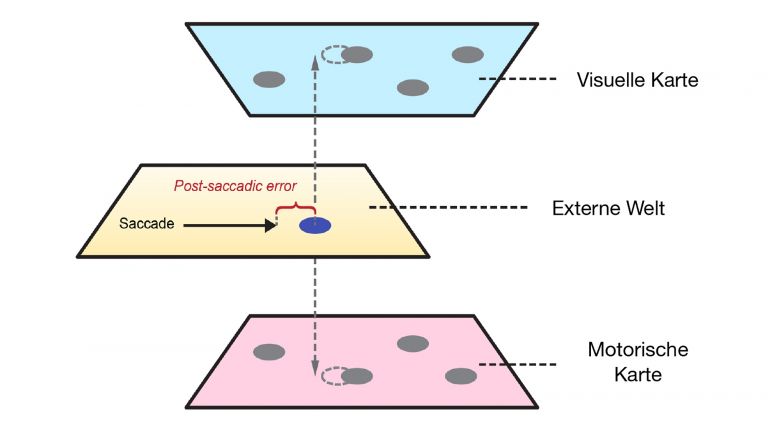

The flow of information into the cerebellum is much more pronounced than the output: for every nerve fiber that leaves it, 40 nerve fibers enter. Via – in some cases extremely large – pathways, the cerebellum constantly receives a flood of information from the visual organ, the spinal cord, the vestibular system, the brain stem, and various areas of the cerebral cortex, including the premotor cortex. This means that it is constantly aware of what movement is currently being planned, what position the body is in, and what motor actions the body is currently performing. The cerebellum coordinates all this information: it compares what is intended with what has already happened. If it is foreseeable that the movement in progress will not lead to the desired goal, the cerebellum sends correction signals to the motor system. This modifies the movement and steers it back onto the right track.

Minus times minus equals plus

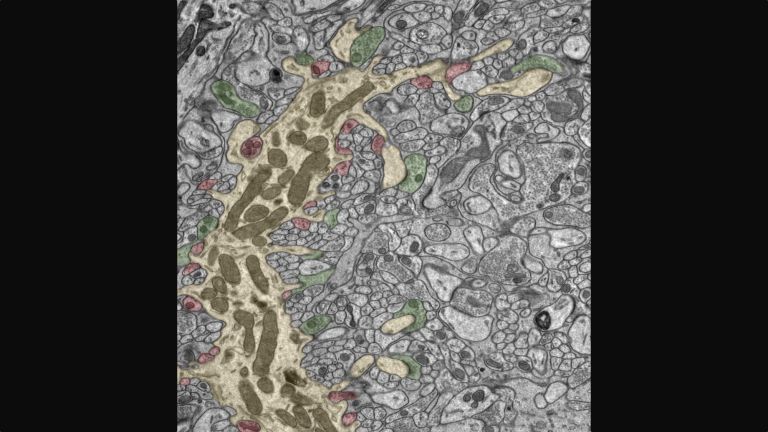

Like the cerebrum, the cerebellum is divided into an outer cortex and an inner medulla. The medulla contains the cerebellar nuclei, areas with densely packed nerve cell bodies. Different types of nerve fibers approach the cerebellar nuclei, bringing information from different parts of the body. This enables the cerebellum to compare everything with each other. The nuclei themselves send their signals back to the motor pathways in the spinal cord and via the thalamus to the cerebral cortex.

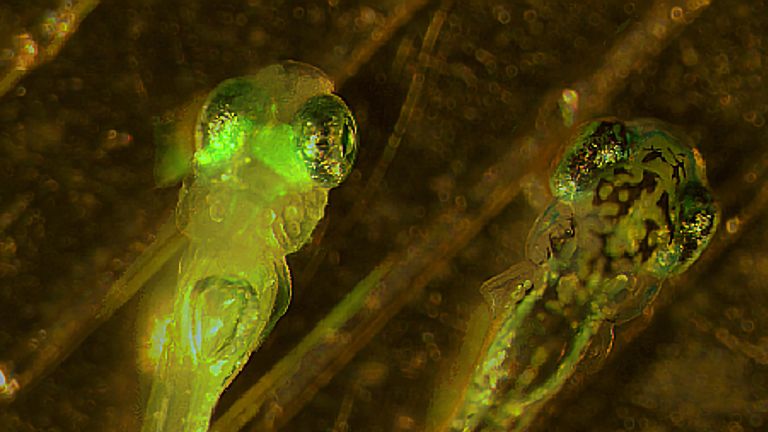

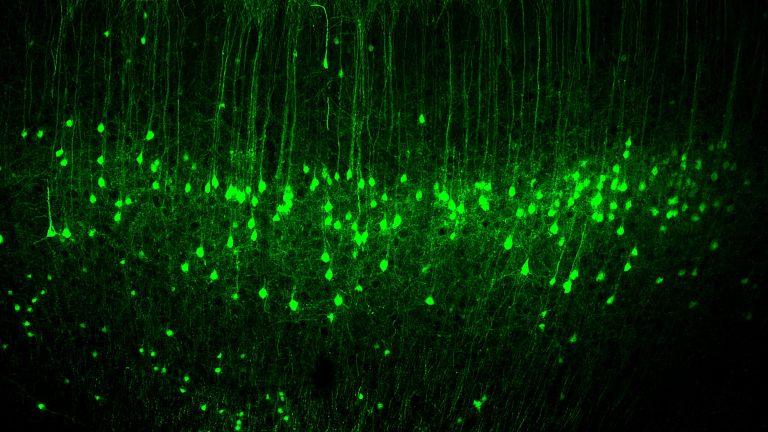

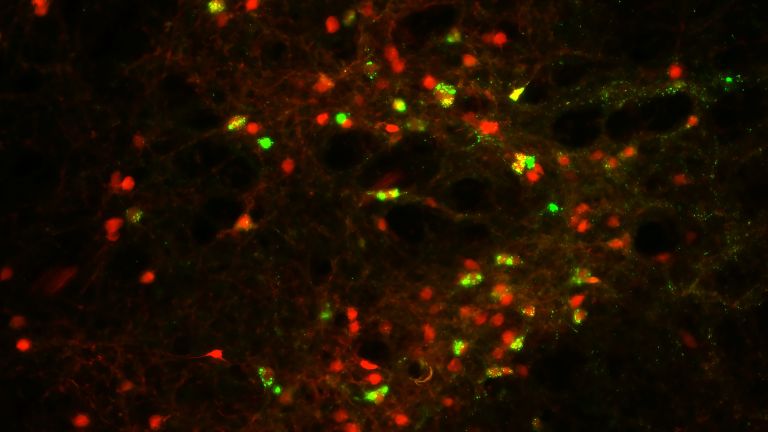

All information from the body that reaches the cerebellar nuclei also reaches special nerve cells in the cerebellar cortex, the conspicuously large Purkinje cells, with a minimal time delay. These cells, named after their discoverer, the Czech physiologist Jan Evangelista Purkyně (1787–1869), constantly inhibit the cerebellar nuclei and prevent them from transmitting their signals “outward.” Only when the Purkinje cells themselves are inhibited can the cerebellar nuclei transmit signals. In this way, the cerebellar cortex with its Purkinje cells modifies the flow of information that passes through the cerebellar nuclei, enabling movements to be performed in a targeted manner without overshooting.

Large amounts of alcohol interfere with the function of the cerebellum. Therefore, the symptoms of a person with cerebellar disease resemble those of a drunk person: they suffer from balance disorders, walk with a wide stance and stagger. In addition, they speak in a choppy manner, their movements are erratic and overshoot the mark. If you hold their arm and ask them to resist, then suddenly let go of their arm, they cannot slow down in time: their fist hits them in the face. Incidentally, chronic alcohol abuse causes the cerebellum to shrink permanently.

Recommended articles

Of dogs, bells, and blinking eyes

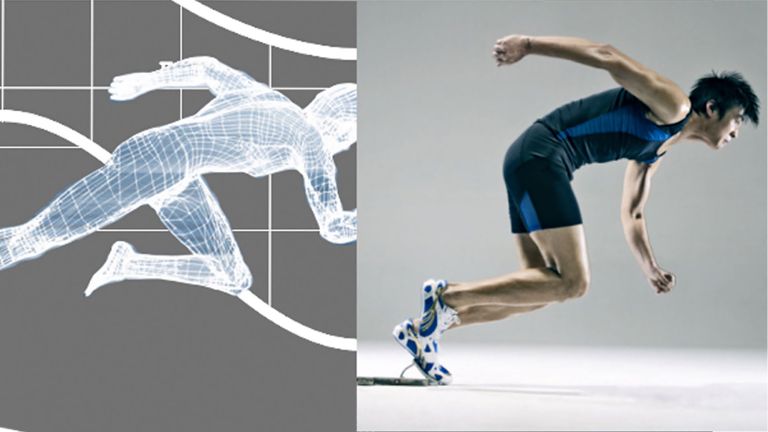

Today we know that the cerebellum ensures that we can perform learned movements correctly. And what's more, new movement sequences are also stored and automated in its circuits, such as when someone learns to ice skate.

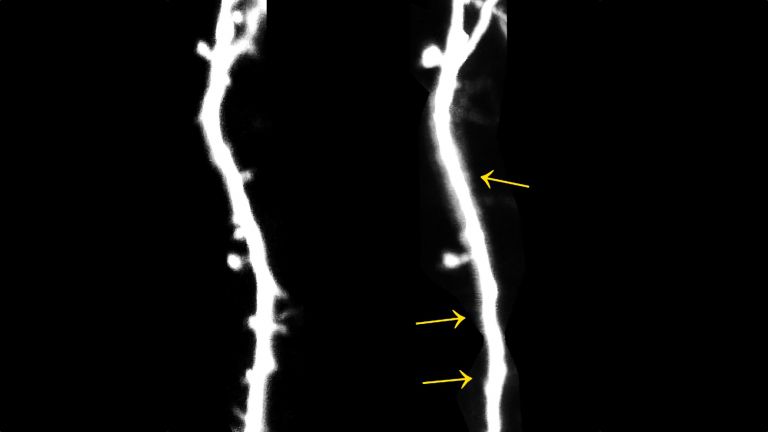

The hypothesis that the cerebellum also plays a decisive role in motor learning processes was first formulated in the 1970s. As we know from one of the most famous experiments in behavioral research, Pavlov's dog learned to salivate when a bell rang – even when there was no food in sight. Similarly, humans learn to blink when they hear a sound – provided they have been presented with a puff of air at the same time as the sound often enough. Research shows that new nerve cell connections are then formed in the cerebellum, or existing ones are strengthened. This process is known as synaptic plasticity, and it provides our current knowledge on the basis of memory formation. This is how the new reflex becomes anchored in the depths of the cerebellum after a while. If the cerebellum is damaged, this learning process no longer works.

Making the right choice

The basal ganglia, a collection of interconnected core areas in the brain that receive all information about a planned action, also play an important role in coordinating learned movements. They evaluate possible movement patterns and choose between appropriate and inappropriate ones. In this way, they control the strength, extent, speed, and direction of a movement. They send the result to the thalamus, a part of the cerebrum that is referred to as the “gateway to consciousness.” The thalamus forwards the relevant information to the cerebral cortex, which sends the impulses for movement.

The basal ganglia and thalamus together form a filter that ensures that exactly the right movement patterns reach the cerebral cortex and are passed on to the spinal cord and muscles for execution. If this filtering process no longer functions properly, both the initiation and execution of movements are disrupted. What this looks like depends on whether the disrupted system filters out too much or too little: In the first case, the result is a lack of movement; in the second case, unwanted excessive movements.

In Parkinson's patients, too much gets stuck in the filter, so fewer movement impulses reach the cerebral cortex. The patients' facial expressions are rigid, they swallow less frequently, and their arms swing less when walking. Since they hardly lift their feet, they often stumble and fall. Muscle stiffness and slow tremors are also typical. In the hereditary disease Huntington's chorea, on the other hand, the filter allows too many signals through, and patients have little control over their muscles, with sudden and unexpected movements occurring. Those affected make grimaces or flail their arms and legs.

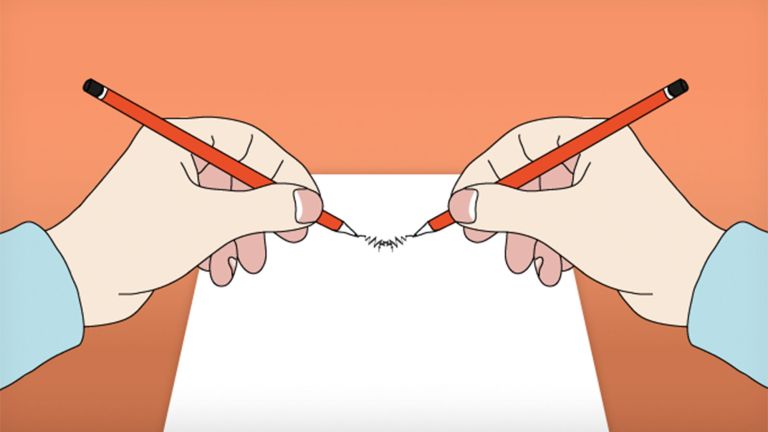

The filtering process in the basal ganglia is particularly important for performing complex, learned movements, such as writing. If part of the basal ganglia fails, a patient's handwriting resembles that of a child starting school.

Both the cerebellum and the basal ganglia are important parts of motor function, although they cannot initiate movements themselves. If these parts of the brain fail, those affected are not paralyzed, but they are unable to perform voluntary movements in a targeted and precise manner at the right time.

First published on August 23, 2011

Last updated on December 1, 2025