Highway through the Spinal Cord

Movements are largely controlled by the brain. In order for these motor commands to be executed, they must reach the muscles. This task is performed by specialized nerve pathways in the spinal cord – our motor highways.

Scientific support: Prof. Dr. Hansjörg Scherberger

Published: 01.12.2025

Difficulty: intermediate

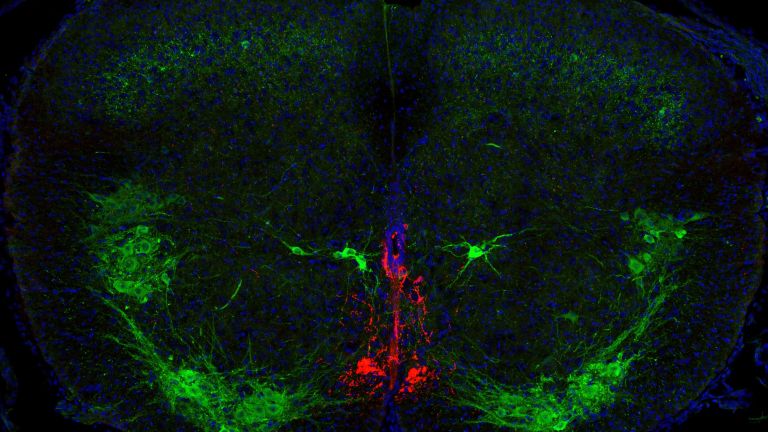

- Several motor pathways run from the brain to the spinal cord and then down to the muscles. The movement centers of the cerebral cortex communicate with the muscles via these descending spinal cord pathways.

- In primates, the pyramidal tract is responsible for voluntary movements and, in particular, for the fine motor skills of the hands and fingers. This makes it probably the most important motor pathway in humans.

- In the spinal cord, the pyramidal tract is connected either directly or via interneurons to the motor neurons, which transmit motor signals to the muscles and cause them to contract.

- The ventromedial pathways control balance and posture. The associated muscle movements are usually unconscious.

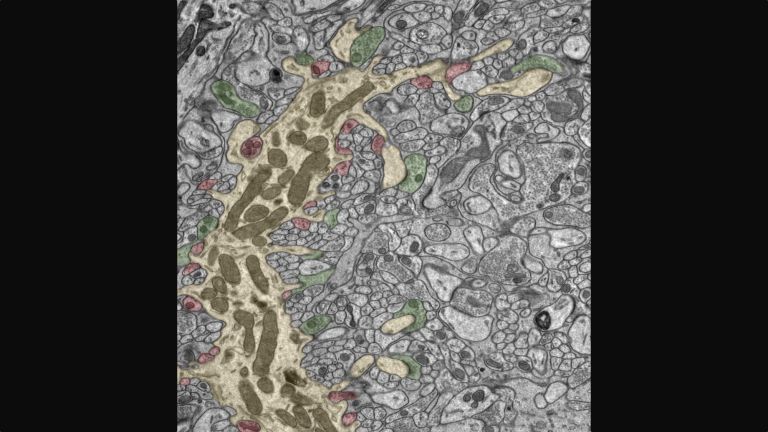

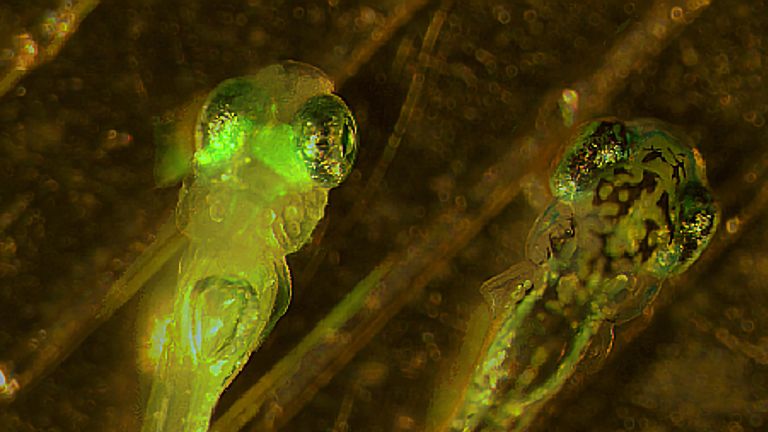

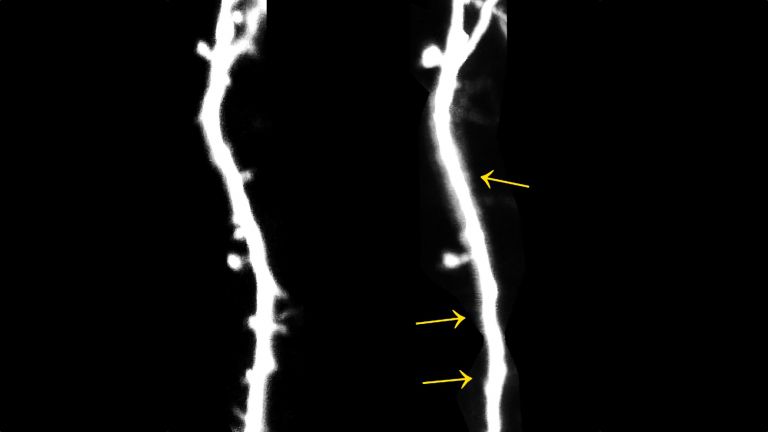

The motor neurons in the spinal cord are responsible for muscle contraction. The extensions of the motor neurons widen at their ends to form motor end plates, which attach them to the membranes of the striated muscle fibers. When a motor neuron in the spinal cord receives a signal to contract, for example via the pyramidal tract, the motor end plate releases vesicles: small bubbles containing the neurotransmitter acetylcholine. When the chemical messengers reach the muscle cell, they dock onto receptors there and trigger electrical excitation of the cell, which then contracts.

The arrow poison curare interrupts communication between the brain and the muscle at the motor end plate: the substance attaches itself to the acetylcholine receptors and blocks them. Acetylcholine can then no longer dock onto the receptors and thus no longer trigger muscle excitation; its effect virtually evaporates into thin air. The result: the muscle can no longer contract. Since the respiratory muscles are also paralyzed, respiratory arrest and ultimately death occur. South American indigenous peoples produce the arrow poison from the bark and leaves of South American liana species and use it to hunt animals. Since curare is not fatal when it enters the body through the gastrointestinal tract, the meat of the hunted animals is edible for humans.

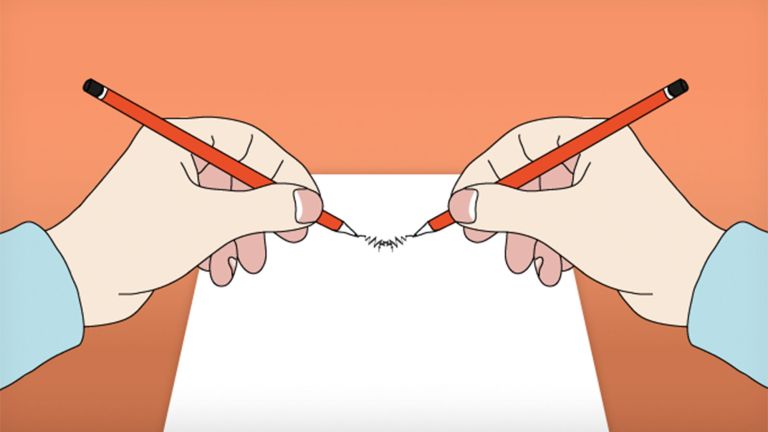

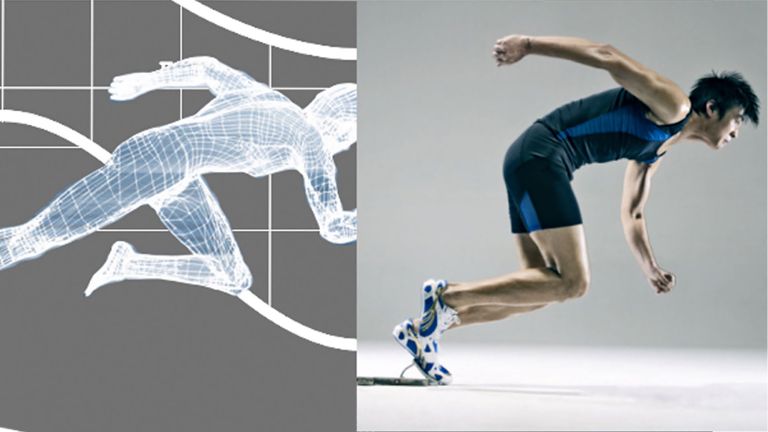

The “A” with the left little finger, the “I” with the right middle finger: anyone who wants to learn to type on a computer keyboard using the ten-finger system has to practice diligently. The fact that we can move our fingers and the rest of our body so quickly and precisely at will is thanks to a multi-lane motor highway from our brain to the spinal cord. This allows the brain to initiate and coordinate movements at lightning speed.

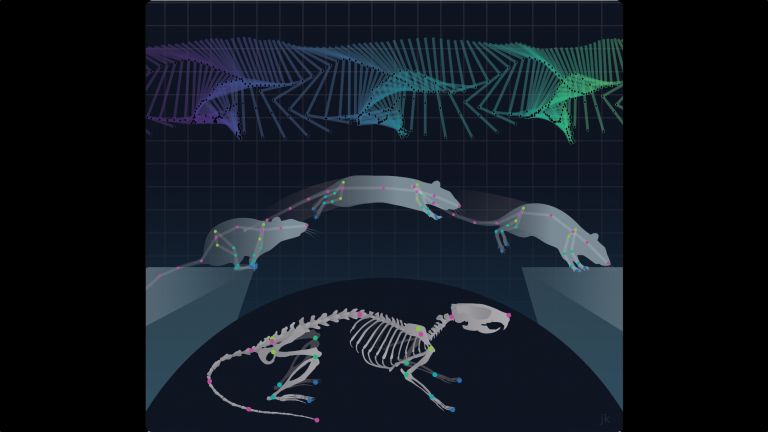

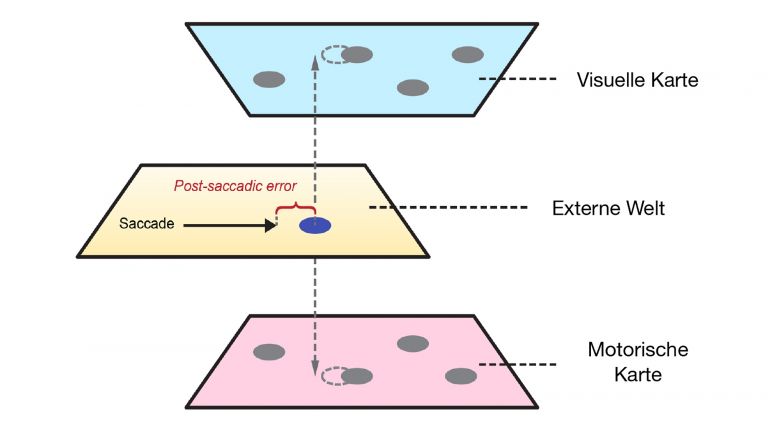

Every voluntary movement begins in the brain, more precisely in the premotor cortex. This is the part of the cerebral cortex that designs and initiates individual movements. The premotor cortex coordinates the movement program with other parts of the brain and forwards its conclusion to the primary motor cortex, which collects all signals and divides them into individual tasks. How skillfully we can use a part of our body depends on how many nerve cells are responsible for that part of the body. The areas for the hands and fingers are particularly large, which is why we are able to produce fine drawings or build tiny clockworks. However, other areas of the brain are also responsible for movement, coordination, and muscle tone – in particular, the cerebellum and basal ganglia.

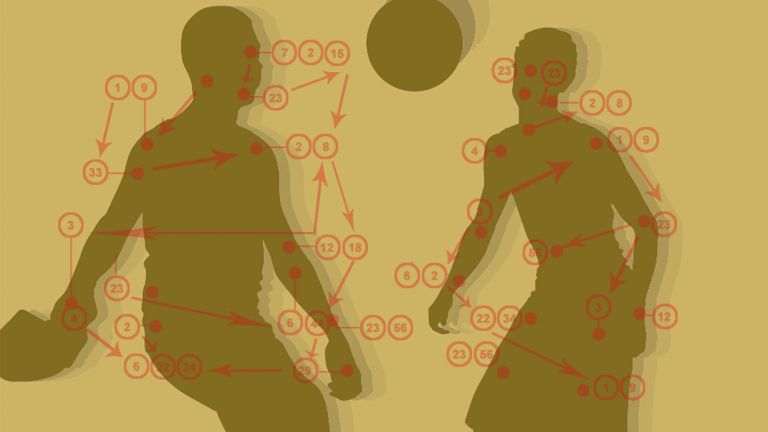

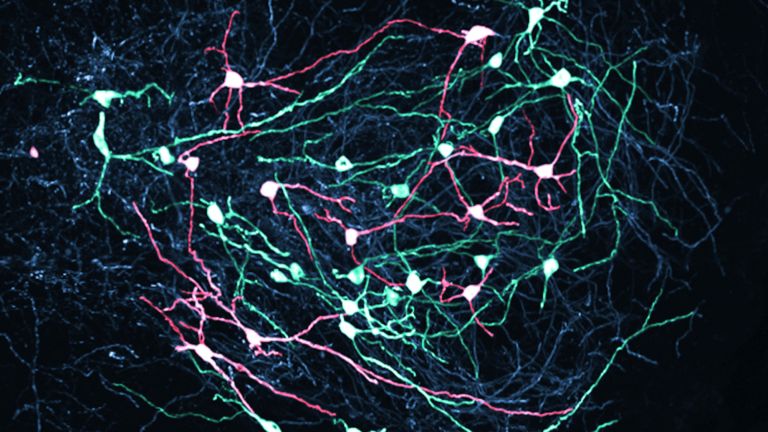

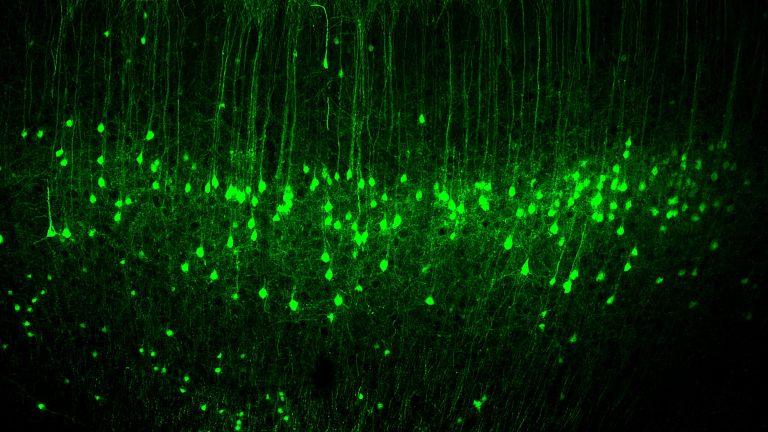

The axons of the nerve cells from the motor areas of the cerebral cortex bundle together to form various nerve pathways which, in some cases after an initial connection in the brain stem, travel to the spinal cord. These descending spinal cord pathways carry motor commands down to the neural network of the spinal cord, which causes the muscles to contract – in the case of typing, the hand and finger muscles. The muscles are ultimately activated by the spinal motor neurons, nerve cells that run from the spinal cord to the individual muscles. The descending spinal cord pathways are therefore the highways from the brain to the spinal cord.

Lateral and ventromedial pathways

The function of each nerve pathway can be roughly determined by its location in the spinal cord: The lateral pathways located on the sides of the spinal cord, with their most important component – the pyramidal tract or corticospinal tract – are responsible for voluntary movements of the extremities, especially the hands and arms, but also the feet and toes. The lateral pathways also include the rubrospinal tract. It originates in the red nucleus located in the midbrain and plays an important role in the movement control of many mammals. In humans, its functions are largely taken over by the pyramidal tract.

The ventromedial pathways, which are located further ventrally, include the vestibulospinal tract, the tectospinal tract, the medial reticulospinal tract, and the lateral reticulospinal tract. These descending pathways originate in different regions of the brainstem and control the trunk and trunk-related limb muscles. Their primary function is to control balance and posture using sensory information. For example, if we are walking down a staircase and suddenly encounter an extra step, proprioceptive reflexes activate the muscles of the hips and thighs via the ventromedial pathways so that we can compensate for the sudden change in position and avoid falling.

The pyramidal system with the pyramidal tract is therefore responsible for conscious movements, especially of the hands and fingers – and thus for things like writing or playing the violin. The extrapyramidal system with the ventromedial spinal tracts, on the other hand, is responsible for the mostly unconscious stabilization of body posture.

Both systems work closely together. Only when the head, shoulder, and upper arm are held stable in a certain position can the hand move the bow across the strings in such a way that Rimsky-Korsakov's famous Flight of the Bumblebee can ultimately be heard.

Recommended articles

The pyramidal tract as a highway

The pyramidal tract is therefore the most important motor pathway from the brain to the spinal cord for the highly developed fine motor skills of the hands. It is only thanks to this tract that we are able to move individual fingers at high speed and with great precision. There is a close connection between its development and the dexterity of the hands and fingers that is characteristic of primates. In other words, in most animals, the pyramidal tract is just a country road, but in primates, it is a highway that carries large amounts of information from the brain to the muscles particularly quickly. The nerve cells that form the origin of the pyramidal tract are up to more than a meter long with their extensions and are therefore not at all microscopically small, as is often assumed of cells.

Incidentally, the name “pyramidal tract” does not come from the pyramidal cells in the primary motor cortex, their main point of origin. Rather, it is named after a bulge they form in the brain stem, the medulla oblongata. There, the corticospinal tract appears triangular in cross-section. At this pyramid, almost 90 percent of all nerve fibers of the pyramidal tract cross to the other side of the body. The remaining nerve fibers also cross, but later, at the level of their target area in the spinal cord. Accordingly, it is always the right hemisphere of the brain that gives the command to type the letter “A” with the left finger.

The pyramidal tract does not come into direct contact with the muscles. The highway ends in the spinal cord, where the spinal motor neuron originates, which controls the muscle to be moved. Motor neurons are nerve cells whose extensions extend to the striated skeletal muscles and cause them to contract (see info box).

However, only in the hand and finger muscles are the pyramidal tract and motor neurons directly connected to each other – which is one reason why we are so dexterous. In other parts of the body, on the other hand, the pyramidal tract first encounters one or more so-called interneurons. These intermediate nerve cells then pass the information on to the responsible motor neuron. On its journey from the brain to the legs and feet, the signal must therefore take a detour via two or three additional highways before it reaches its destination.

Feedback through sensitive pathways

In humans, part of the pyramidal tract also supplies the muscles of the lips, larynx, and tongue, which is one of the reasons why we are the only primates that can speak. Contraction occurs there in exactly the same way as in other parts of the body. However, the nerve bundles from the primary motor cortex do not first travel to the spinal cord because the responsible part of the pyramidal tract branches off earlier, in the brain stem.

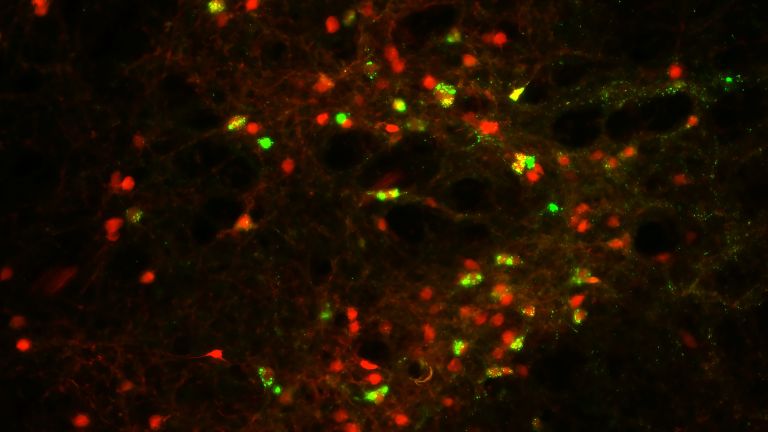

Of course, we never perform movements in isolation; there is always feedback. Parts of the brain constantly receive feedback on how far a movement has progressed and how much force is being exerted. At the same time, the position of the body in space is constantly checked and the movements are adapted to the current situation. This information is also transmitted via pathways in the spinal cord, but this time descending from sensory receptors in muscles, tendons, joints, and skin toward the brain via the so-called sensory pathways.

The journey of motor signals from the brain to the finger muscles is therefore like a highway trip – but one accompanied by many other cars traveling in the opposite direction.

First published on September 1, 2011

Last updated on December 1, 2025