The battle over the neuron doctrine

In the early days of brain research, it was virtually impossible to identify the cells of the brain. When Italian scientist Camillo Golgi discovered the crucial technique for making neurons visible in 1873, researchers disagreed about what they were seeing.

Scientific support: Prof. Dr. Herbert Schwegler, Prof. Dr. Anne Albrecht

Published: 26.08.2025

Difficulty: easy

- In 1873, physician Camillo Golgi discovered a method for staining individual nerve cells, thereby enabling the development of the neuron doctrine – even though he adhered to the opposing theory that nerve cells form a coherent cell structure.

- Santiago Ramón y Cajal's neuron doctrine states that our brain consists of many individual, independent nerve cells that communicate via contact points.

- The neuron doctrine forms the basis of today's neuroscience, even though some exceptions are now known.

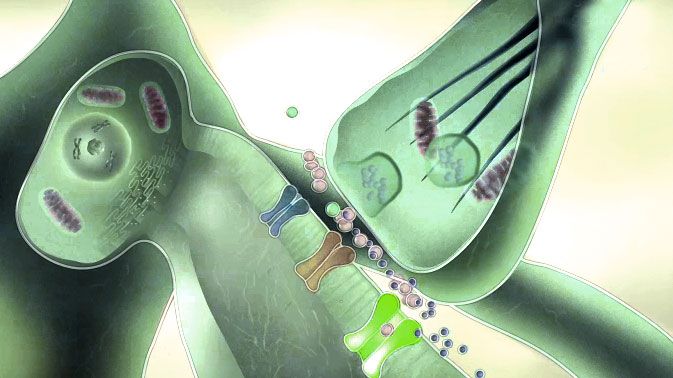

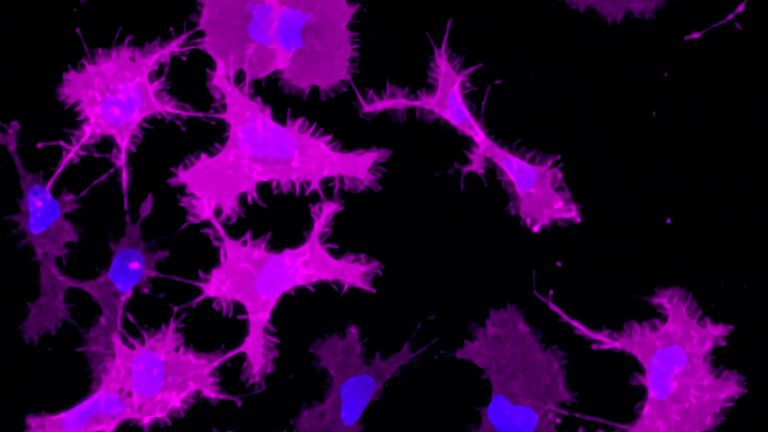

The term “neuron” for nerve cells as the smallest unit of the nervous system was coined in 1891 by Heinrich Wilhelm Waldeyer. Neurons, with their dendrites and axons, form the basic building blocks of the brain. Their axons have contact points at their ends with the dendrites of other neurons, creating a network – but not a random one. This view was contrary to the prevailing opinion at the time that the brain was a coherent cell structure and that the nerve network functioned as a single unit.

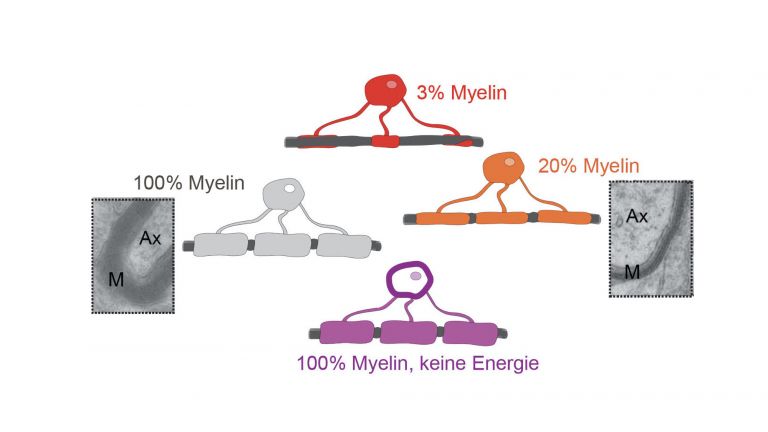

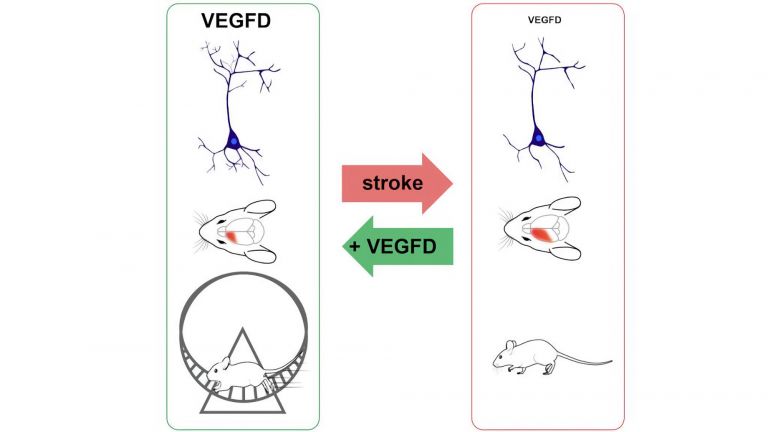

Although these statements have been confirmed to this day, the neuron doctrine needs to be expanded in some areas. For example, electrical synapses are a mechanism that allows many cells to act as a single unit. And according to current knowledge, the role of dendrites is also far from being merely that of passive recipients of commands.

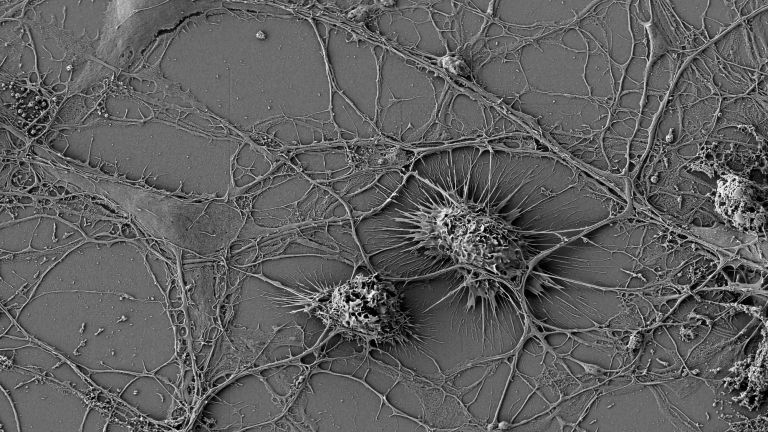

Neurons cannot be seen with the naked eye, as the cells in our brain have an average diameter of 0.01 to 0.05 millimeters. The human hair is about 0.1 millimeters thick, which is up to ten times larger. It was not until the development of compound microscopes in the late 17th century that researchers were able to descend to the cellular level of the brain.

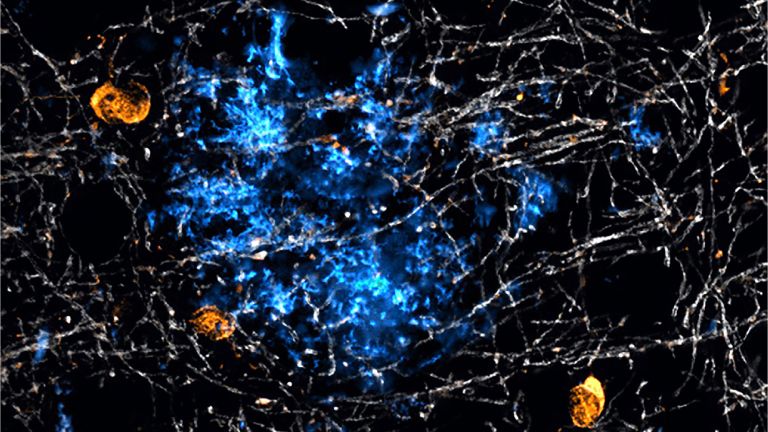

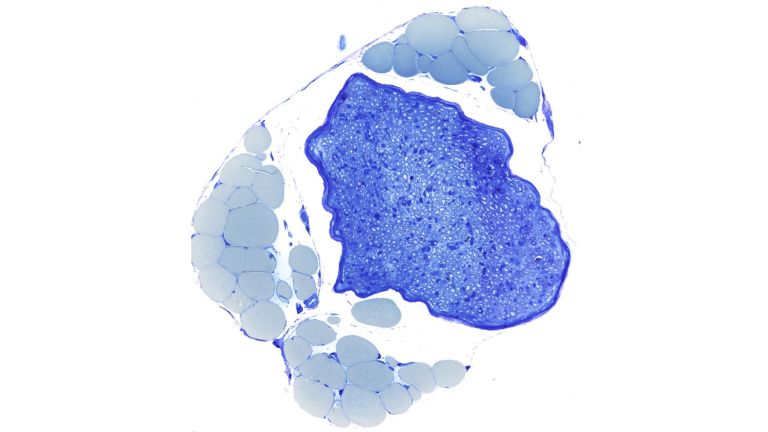

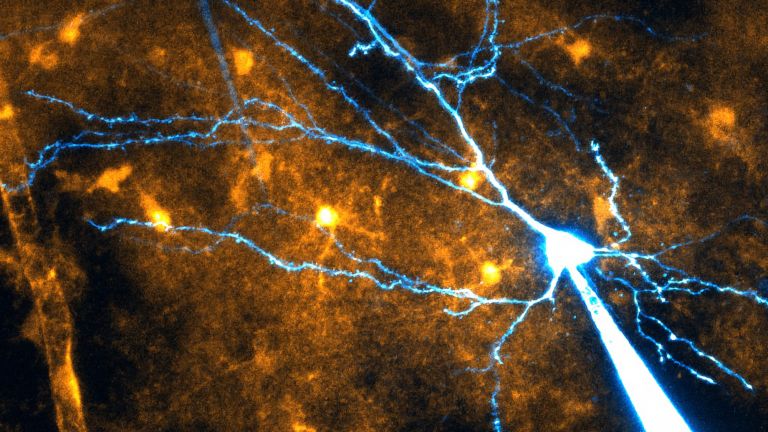

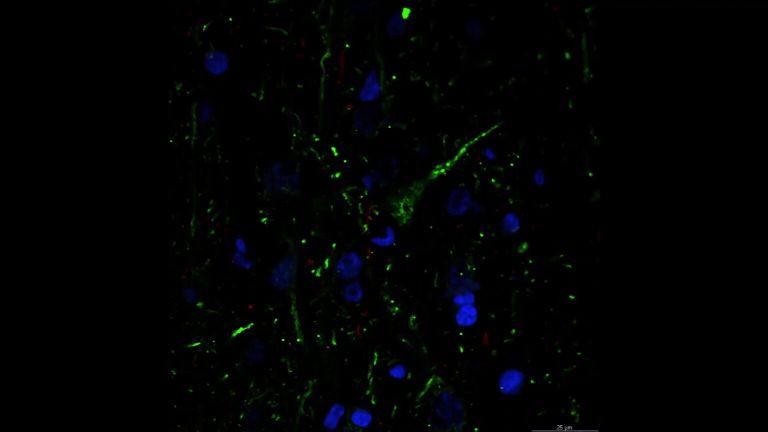

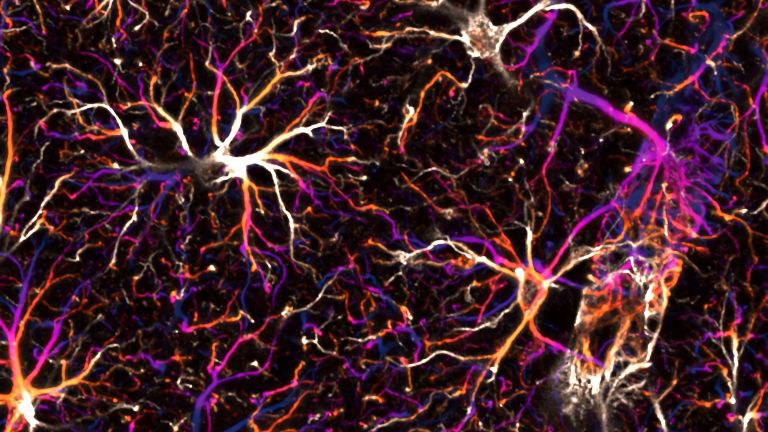

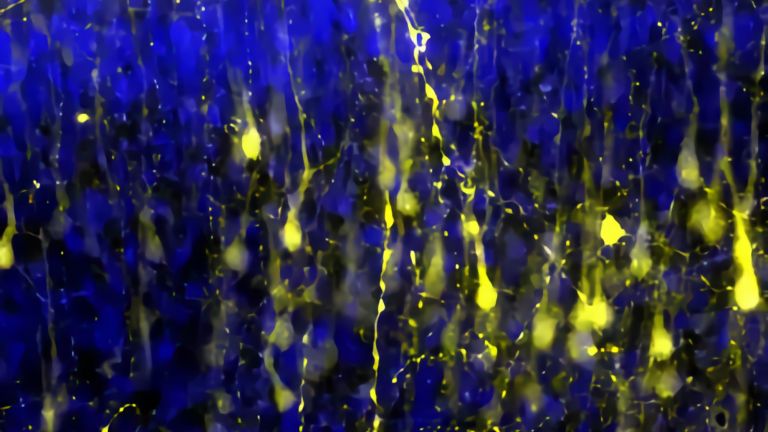

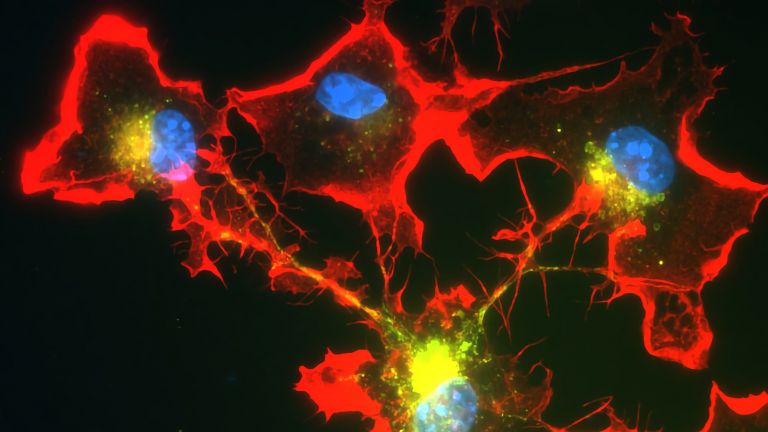

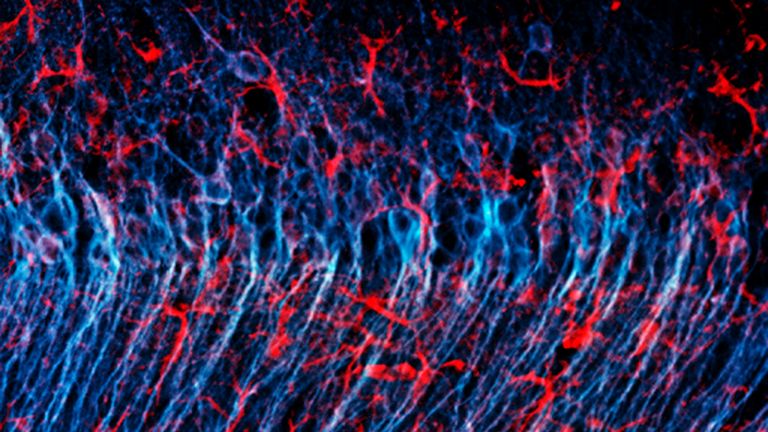

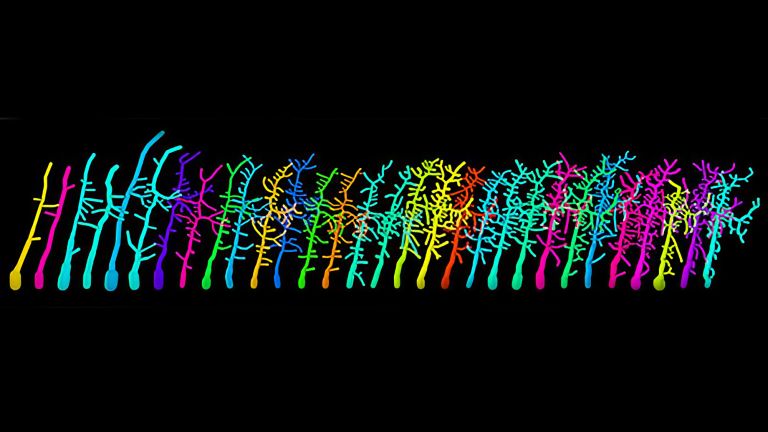

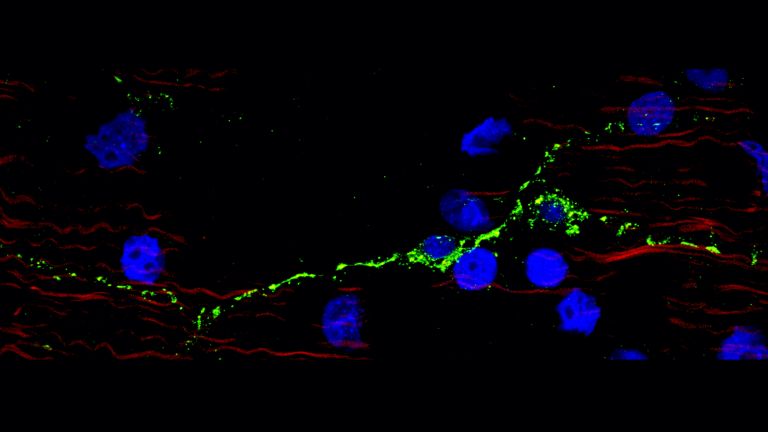

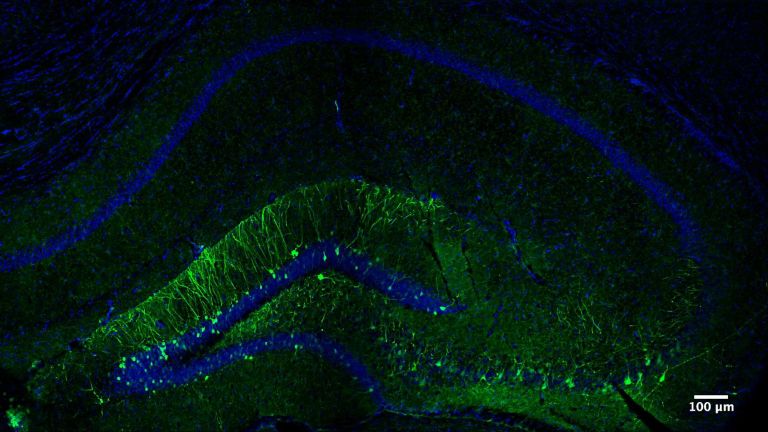

The method used by Cajal and Golgi also has its pitfalls. Although it shows the silhouette of individual neurons in great detail through the incorporation of silver compounds, it only shows a few neurons in the tissue. Other staining methods are needed to obtain an overview of all neurons in a brain region.

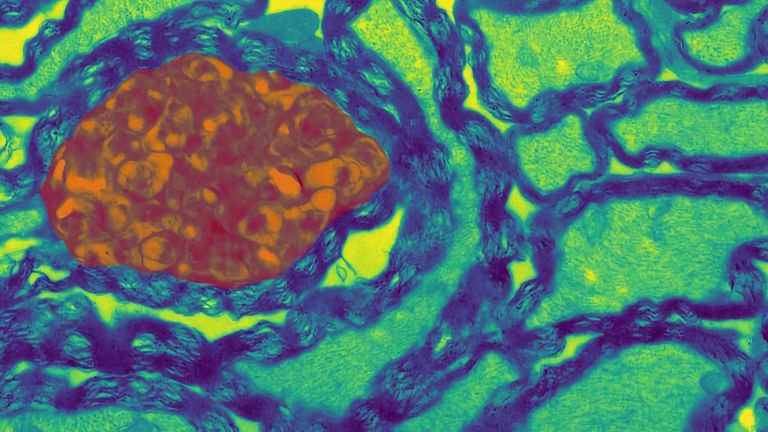

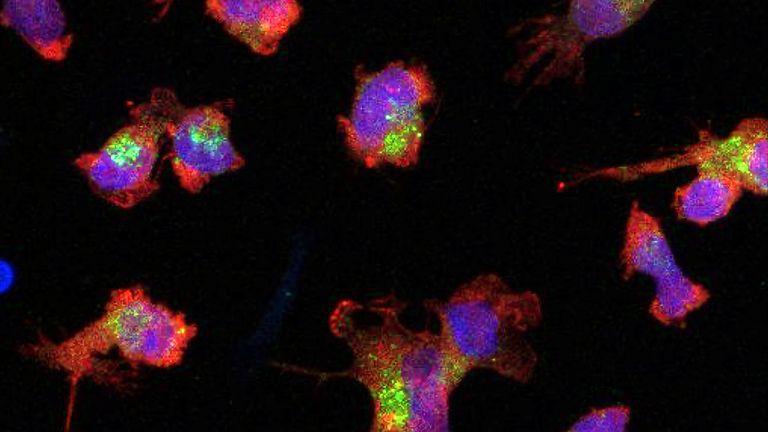

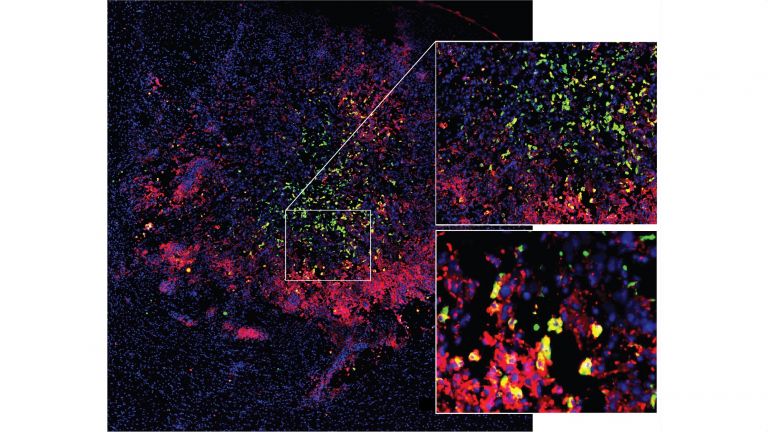

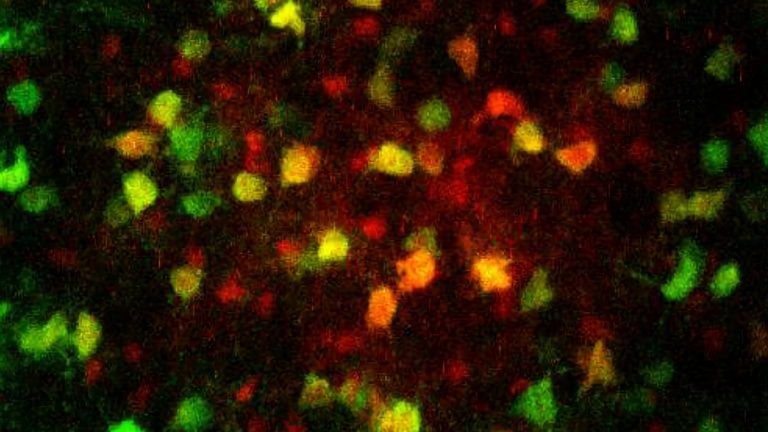

Nissl staining, invented in 1894 by brain researcher Franz Nissl, uses basic dyes that attach themselves to structures in the cell bodies of neurons. This allows the number, structure, and arrangement of neurons in different areas of the brain to be compared.

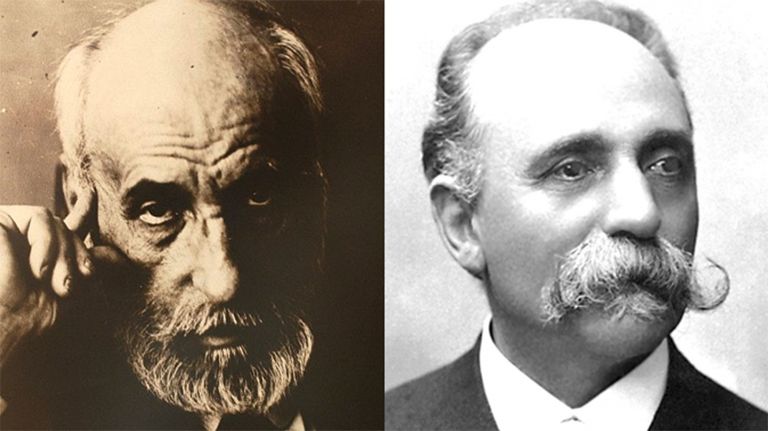

Winning a Nobel Prize can be annoying – if you have to share the trophy with your worst adversary. At least, that's what happened to Italian physician Camillo Golgi (1843-1926) and Spanish anatomist Santiago Ramón y Cajal (1852-1934). In 1906, they jointly received the Nobel Prize in Medicine “in recognition of their work on the structure of the nervous system”. However, while Cajal assumed that the brain consisted of individual autonomous nerve cells, or neurons, Golgi believed that the nerve fibers formed a continuous network of cells, similar to the blood circulation.

The feud between the two was so bitter that Golgi couldn't resist picking apart his colleague's neuron theory in his Nobel Prize speech. He emphasized that “none of the arguments ... would stand up to scrutiny”. Meanwhile, Cajal trembled with impatience in the audience because, as he later wrote, politeness prevented him from “correcting so many abominable errors and so many deliberate omissions”. Accordingly, he later judged Golgi harshly in his autobiography: “One of the most conceited and self-admiring talented men I have ever known.” Yet it was Golgi's discovery that had made Cajal's findings possible.

Nerve cells: tiny, colorless, and chaotic

More than thirty years before the award ceremony, in 1873, the young Camillo Golgi worked as chief physician in a hospital for the chronically ill in Abbiategrasso, a small town in Lombardy. He set up a primitive laboratory in the hospital kitchen, which he himself described as “not even the embryo of a laboratory”. But at the end of the 19th century, a light microscope and dissection tools were enough for him to start a scientific revolution.

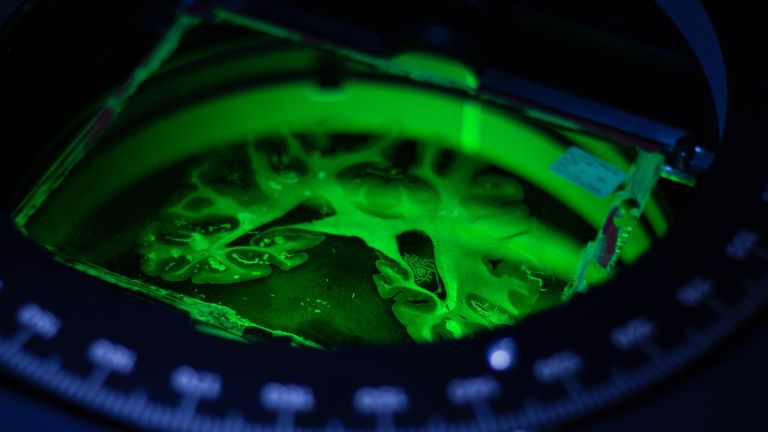

For several days, a piece of brain tissue had been lying in Müller's fluid (potassium dichromate) in Golgi's improvised laboratory to harden. When untreated, the brain has a consistency similar to jelly. At the beginning of the 19th century, however, scientists had succeeded in hardening cell tissue using chemical agents and cutting it into very thin slices with new cutting devices called microtomes. This made it possible to view brain tissue under a microscope for the first time.

Initially, however, the specimens were uniformly cream-colored, so that even with magnification, it was difficult to see anything. It was only when the anatomist Joseph von Gerlach (1820-1896) stained specimens with carmine dye, which is extracted from dried scale insects, that he was able to see more: the cell nuclei of the tissue section glowed deep red. Within a short time, researchers in the still young field of histology, i.e., the examination of tissue samples, tested various dyes from the textile industry. Some marked the cell nucleus, others the cell body or the nerve fibers. However, most of the stained specimens still looked very confusing.

Lucky break: the “black reaction”

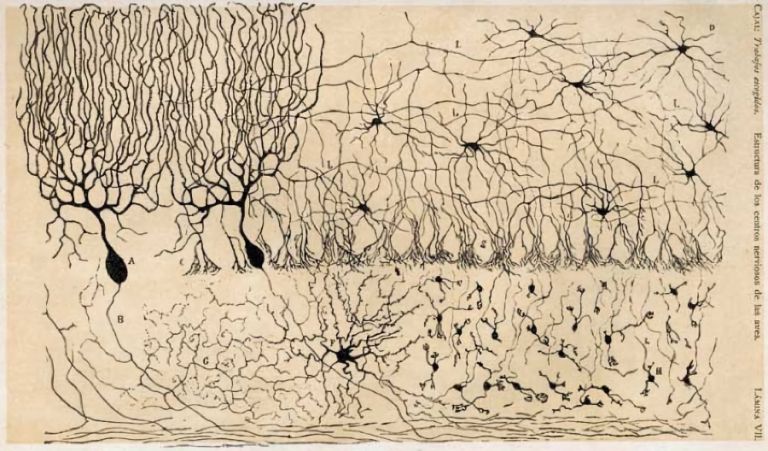

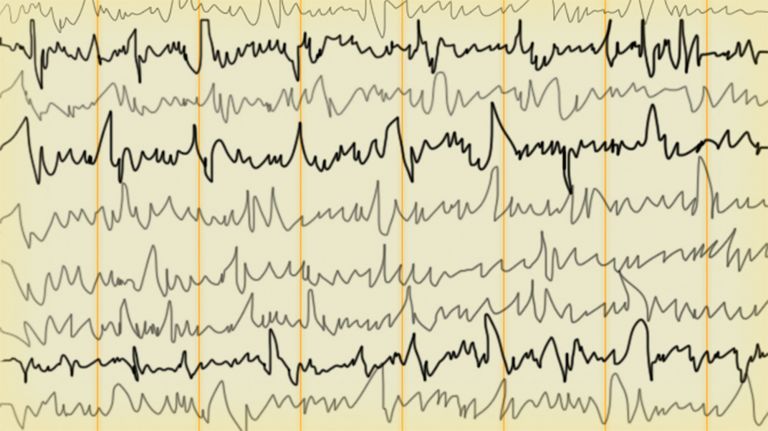

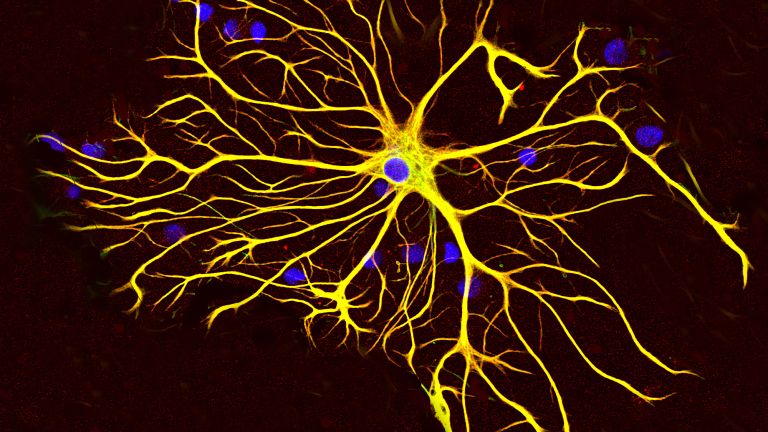

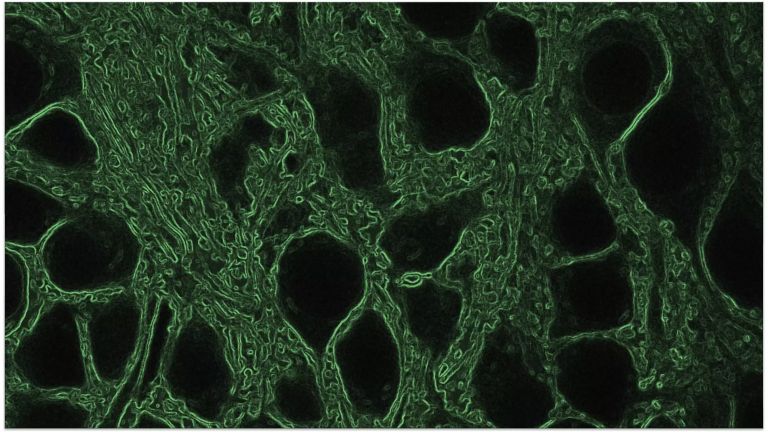

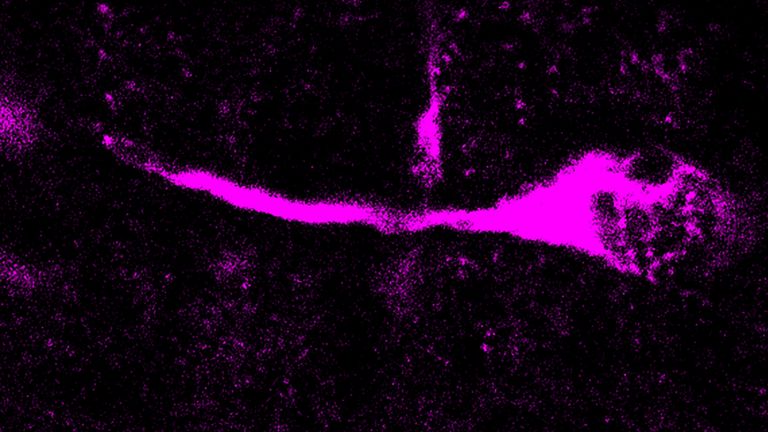

Golgi also wanted to stain the tissue, which had now hardened, in his improvised laboratory. However, he did not use carmine but immersed it in a bath of silver nitrate – whether out of absent-mindedness or curiosity is not known. The histologist cut the glittering specimen into fine strips, dehydrated them, clarified them, and examined them under the microscope. “What an amazing sight!” his colleague Cajal described in 1909 in “Histologie du systéme nerveux de l'homme et des vertébrés” (Histology of the Nervous System of Humans and Vertebrates). “On a yellow, completely transparent background, thinly scattered black fibers appear, smooth and small or spiky and thick, and black, triangular, star- or spindle-shaped bodies, like ink drawings on transparent Japanese paper!” Golgi had succeeded in coating individual nerve cells with silver through a chemical reaction, thereby making them visible as a whole.

Santiago Ramón y Cajal was enthusiastic about his colleague's new method, the “black reaction”. He went on to write: “The eye looks on in amazement, accustomed to the inextricable images of carmine and hematoxylin stains, which forced the mind ... to an ever-questionable interpretation. Here, everything is simple, clear, without confusion.” The clarity of the new staining is based on a simple trick: Only one to five percent of all cells are stained in Golgi staining—the rest of the tissue remains invisible. Instead of a jumble of overlapping nerve cells, individual neurons can now be identified.

Recommended articles

One sight – two opinions

Cajal further developed Golgi's method, staining nerve cells, mainly from chickens and small mammals, and published around 45 papers on the nervous system between 1888 and 1891. He produced many drawings based on the staining, which can still be found in textbooks today. However, the connections were not as simple and clear as Cajal had hoped. This was because he and Golgi drew different conclusions from the stained nerve tissue. Golgi claimed that the nerve fibers were connected to each other like the threads of a spider's web. Cajal, on the other hand, argued that the brain consisted of autonomous cells that only communicated with each other via contact points. This neuron doctrine formulated by Cajal “is both the starting point and the basis of neuroscience,” says neuroscientist Douglas Fields of the National Institute of Health in Bethesda, Maryland (see info box).

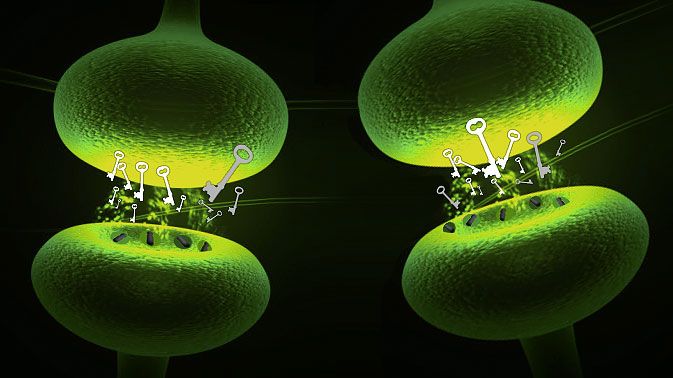

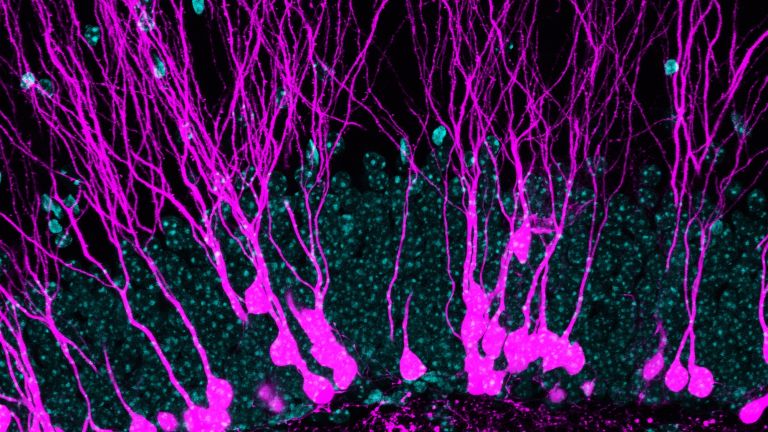

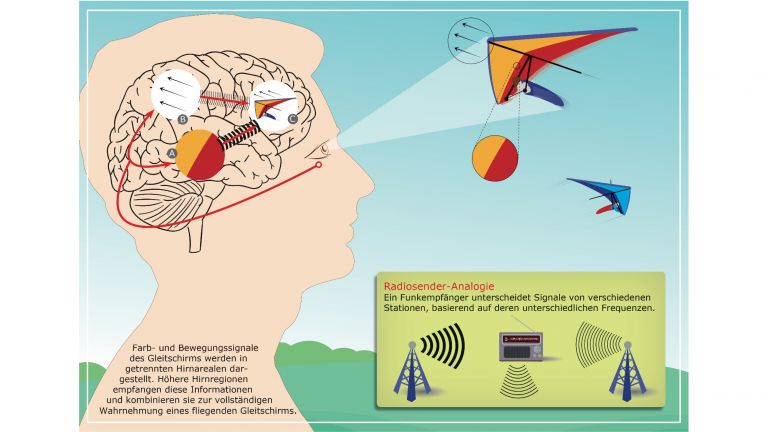

In numerous drawings, Cajal meticulously reproduced the components of neurons: the cell body with its nucleus and the fibers extending from it, the axon and the dendrites. The axon of a cell resembles a long, thick cable that can extend over several meters. The dendrites, which are only a few millimeters long at best and extend from the cell nucleus, look more like moss-like growths on the cell body. Based on the appearance of the cells, Cajal concluded that the axons transmit information like wires and the dendrites receive signals like antennas.

The christening and the final proof

Evidence for the neuron theory was mounting, but the theory still lacked a name. The term “neuron” was coined in 1891 by Heinrich Wilhelm von Waldeyer-Hartz (1836-1921). The anatomist clearly had a knack for catchy words, as we also owe him the term “chromosome.” In a review of the anatomy of the central nervous system, he stated: “The nervous system consists of numerous anatomically and genetically unrelated nerve units (neurons).”

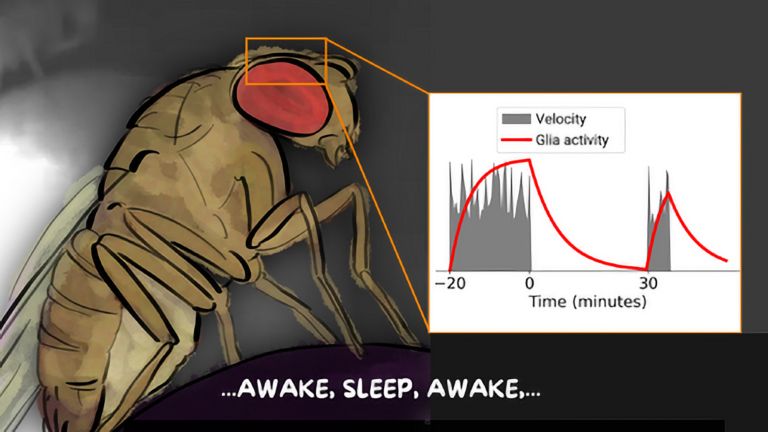

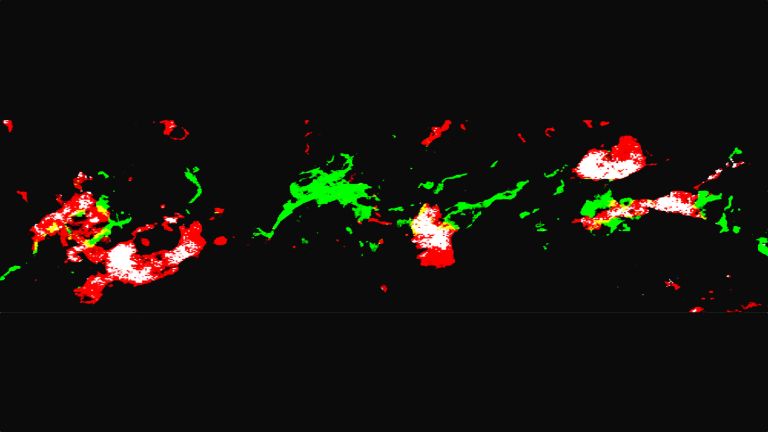

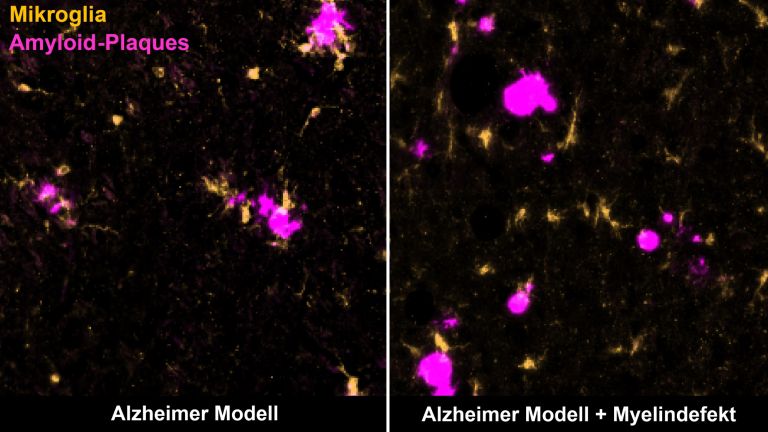

It was not until the 1950s that the newly invented electron microscopes finally proved Cajal right. Such devices finally made it possible to detect the synaptic cleft, only 0.5 nanometers wide, which separates the synapses of two nerve cells. In many cases, neurons also communicate in the direction postulated by Cajal: from the axons to the dendrites. However, neurobiologists have also discovered numerous exceptions in recent years. “We now realize,” explains Douglas Fields, “that the doctrine is not entirely correct: information sometimes travels backwards between neurons. And there are other cells in the brain that communicate without electricity, the glia. Nevertheless, the neuron doctrine is the basic idea of how the nervous system works.”

Further reading

- Bentivoglio, M. et al.: Camillo Golgi and modern Neuroscience. In: Brain Research Reviews 66 (1 – 2), S.1 – 4, 2011.

- Fields, D.: The Other Brain. The Scientific and Medical Breakthroughs That Will Heal Our Brains and Revolutionize Our Health. Simon & Schuster, 2011.

- Pannese, E: The black reaction. In: Brain Research Bulletin. 1996; 41 (6), S. 343 – 349 (Abstract).

- Nobelpreis.org; URL: http://http://nobelpreis.org/; Webseite.

First published on April 10, 2012

Last updated on August 26, 2025