Neurogastronomy – the New Science of Taste

The human sense of smell is no worse than that of other vertebrates. It has simply specialized in a different way: in the creation of taste. The new discipline of neurogastronomy explores the complex human taste system.

Scientific support: Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Meyerhof, Dr. Maik Behrens

Published: 02.09.2025

Difficulty: intermediate

- The human sense of smell is not bad. It is simply specialized – in its role in the creation of taste experiences.

- The sense of smell, the sense of taste, and the brain's interpretation of these senses interact in a unique way.

- Neurogastronomy explores how the human taste system works – and at the same time aims to shed light on how industrially produced food is manipulated.

Aristotle wrote that our sense of smell is worse than that of all other living creatures and the weakest of the human senses. Gordon M. Shepherd (deceased 2022), former professor of neuroscience at Yale University, disagreed. He argued that the human sense of smell is simply highly specialized, with its strength lying in the key role it plays in the creation of taste experiences. Shepherd was convinced that it is our sense of smell that gives us a taste experience unlike any other in the animal world.

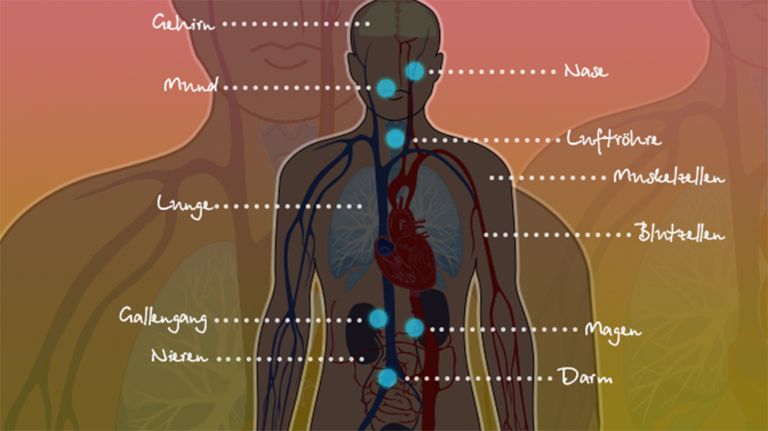

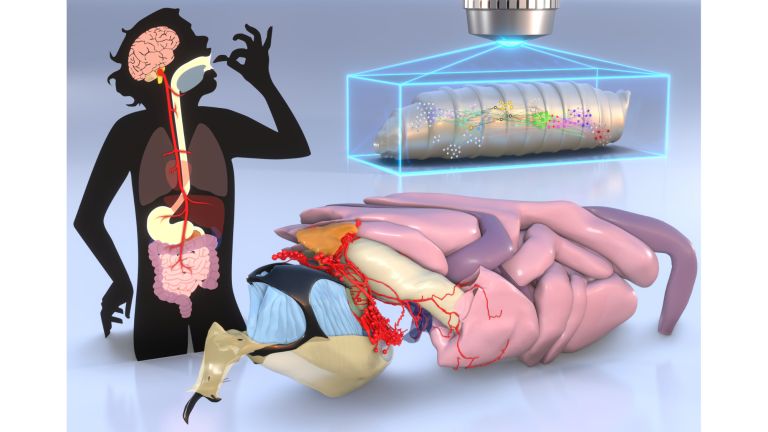

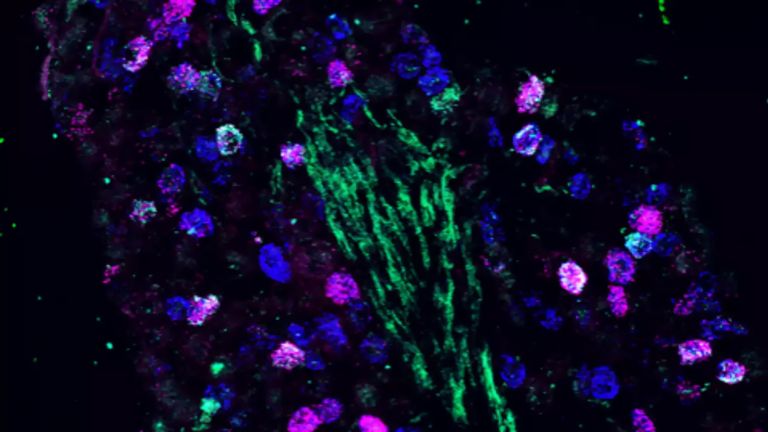

Anyone who has ever had a stuffy nose due to a cold knows the effect: when you can't smell, food doesn't taste good either. This does not mean that the nose alone can produce a taste experience. It needs two other players: the tongue, with which we perceive the texture of food and basic tastes, and the brain. Researchers worldwide distinguish between taste and flavor, analogous in the English language, using “flavor” for this interaction between the tongue and nose, between taste and smell.

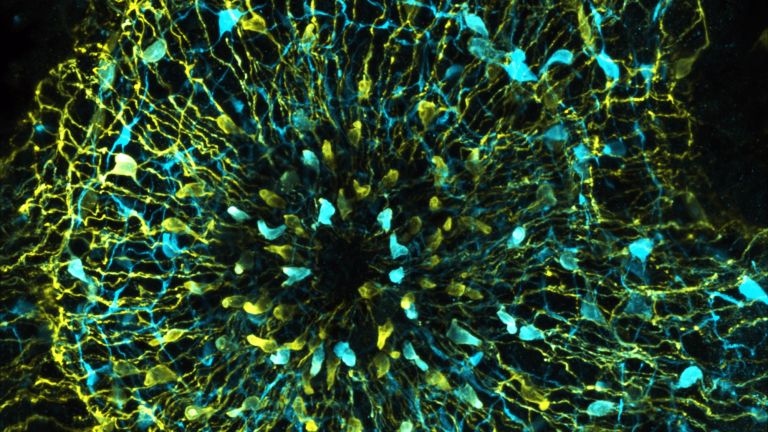

In 2004, Shepherd wrote an article entitled “The human sense of smell – are we better than we think?”. It should have been called “better because we think,” commented a colleague, because flavor is created in the brain. The human olfactory organ is smaller than that of a dog and has fewer receptors. But we can taste so well because we have such a complex brain that interprets the signals from the tongue and nose.

The unique brain-taste system

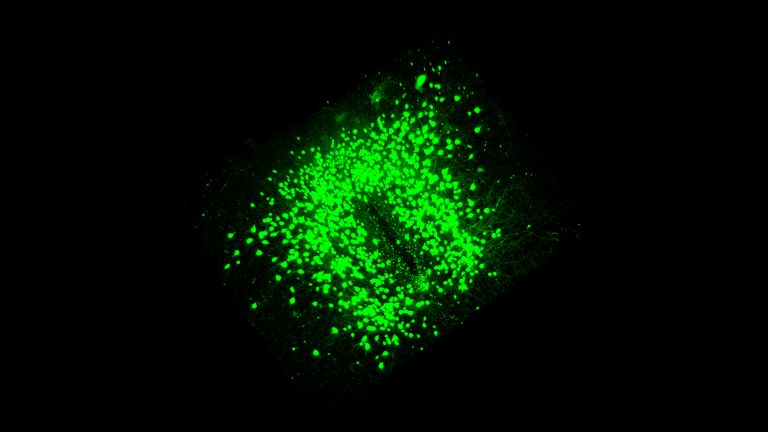

Together, these three – the sense of smell, the sense of taste, and the brain – form what Shepherd called the “unique human brain flavor system.” And he has launched a discipline that attempts to clarify how this system works: neurogastronomy. A neurogastronomist therefore does not run a new kind of trendy restaurant. “We want to understand why we choose the foods we choose. And to do that, we need to understand how the brain produces the taste experience,” said Shepherd.

Per Møller from the Department of Food Science at the University of Copenhagen calls his very similar venture gastrophysics. The name is not important, says Møller, but rather putting questions concerning human food intake, which have so far only been addressed phenomenologically, i.e., based on experience, on a theoretical foundation.

This is not just about basic research. Shepherd had taken up the fight against obesity. “The food industry knows how to make its products irresistible to us,” he lamented in an interview with das Ge hirn .info. “My goal is to inform people about how the taste experience is created so that they can see through these tricks.”

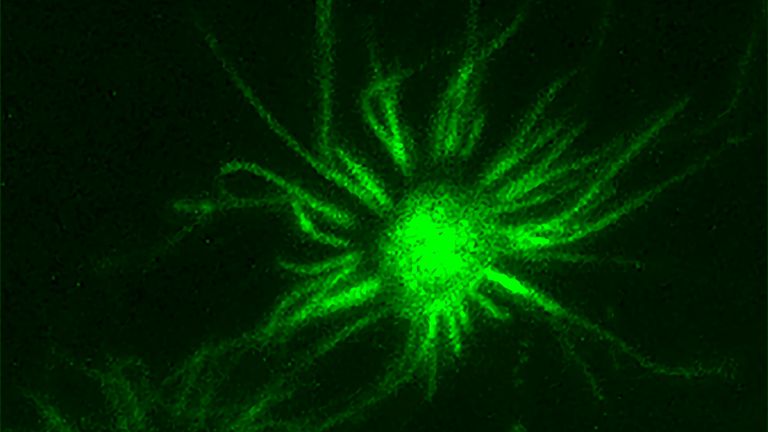

The two pathways of smell

The olfactory system has two pathways: In the anterior, orthonasal pathway, air inhaled through the nose is directed past receptor cells at the top of the nasal cavity. This is how odor molecules from the outside world enter the nose. Orthonasal smelling warns us of gas or fire and provides us with the bouquet of wine, the smell of cooked meals, and the social smells that unconsciously inform us about the gender, mood, and even the immune system of our fellow human beings. The comparatively long dog's nose is specialized for this route of smelling. In humans, it is more of a footpath.

For the human nose, the rear, retronasal pathway plays a greater role. In humans, this is significantly shorter, more direct, and presumably also more efficient than in dogs. In this pathway, air is carried directly from the oral cavity to the olfactory receptors from behind. When eating, this air is saturated with molecules released by chewing food. And since humans began cooking their food, their senses have been confronted with a much greater variety of taste experiences. “Taken together, this leads me to the conclusion that the retronasal pathway gives humans a richer taste experience than other mammals,” said Shepherd.

The taste experience is as little a part of tasty food as colors are a part of colorful objects. It arises when the brain analyzes and interprets the messages from the olfactory receptors and relates them to the messages from the sense of taste and other senses.

This is because many other factors influence how food tastes to us: the eye does not only check food for freshness. As researchers reported in the journal “Flavour,” even the color of the plate and the size and shape of the cutlery influence how food tastes to us. And a pasta salad colored blue with completely tasteless food coloring will not find any takers, even at a children's birthday party. Sunday rolls taste better when you can hear them crunching, and wine tastes better when it glugs gently from the bottle. A mushy peach, on the other hand, has already lost out at the first tactile contact.

In addition to the other senses, the brain's taste system is linked to the neural networks for emotions, memory, consciousness, language, and decision-making. It is one of the most interconnected systems in the brain, according to Shepherd. And he wanted to connect neurogastronomy in a similarly complex way: Disciplines such as anthropology, the evolution of taste preferences, the sociology of food preparation and consumption, developmental psychology, pharmacy, and research into addictive behavior should work together to explain how such a differentiated taste experience can arise, even though we humans are rather sparsely equipped in terms of the number of receptors in our mouths and noses.

Taste as a driving force in human history

Shepherd was convinced that, without us realizing it, the taste of our food is a key driving force in human history. It is no coincidence that trade routes existed as early as Roman times, bringing spices from China to the Mediterranean. Marco Polo sought the route to the East in order to reach the sources of the spice trade. Not least, it was also the spice trade that gave rise to the infrastructures of the world empires. And even today, multinational corporations depend on bringing food and beverages with the right taste to the people. ▸ Fragrant brands

Recommended articles

Why we eat too much

The reason we quickly eat too much of their industrially manufactured products is due to an imbalance between sensory stimulation, calorie content, and satiety value. Fast food contains excessive amounts of flavorings and calories, but little fiber. So we continue to eat and eat and never feel full. In addition, fast food contains many different flavorings. This flatters our brain's taste system, because it reacts most strongly to change. So we continue to eat even though we are actually full: fries, burgers, cola in between, then caffè latte and a chocolate cookie. Emotions and memory do the rest, making it very difficult for us to resist foods with our favorite flavors.

However, we largely have control over what our favorite flavors are. Although we have an innate preference for sweet and fatty foods, everything else is learned. This means that we adapt to the flavors we are frequently exposed to. Even before birth, mothers' eating habits shape their children's preferences. When formulating food recommendations, we must consider whether the brain's taste system makes it difficult or easy for us to follow these recommendations, Shepherd argues.

Paradoxical result

When science began to explore the lowly art of cooking, it had two goals: to better understand what happens when food is prepared, and to improve and enrich that preparation. The best-known result of these efforts is molecular cuisine, with its unusual combinations and preparation methods. “There are some great things out there,” Shepherd admitted. Nevertheless, he and his wife preferred to sit down to a traditional, home-cooked meal. “That's one of my most important messages,” Shepherd said: “Traditional cuisine dishes have a balanced ratio of proteins, fats, and carbohydrates. The food has flavor, is made from good ingredients, and is filling.” This can only be confirmed by a new science such as neurogastronomy.

Further reading

- Gordon M. Shepherd: Neurogastronomy. How the Brain Creates Flavor and Why It Matters, Columbia University Press 2012

- Flavour. Open Access Peer Reviewed Journal. URL: http://www.flavourjournal.com/ [Stand: 02.10.2013], zur Webseite.

First published on November 27, 2013

Last updated on September 2, 2025

![Die Grafik erläutert, wie sich der Neurowissenschaftler Gordon M. Shepherd das komplexe Geschmackserleben des Menschen vorstellt. Grafikerin: Meike Ufer [nach Gordon M. Shepherd, Nature 2006]](https://www.thebrain.info/sites/default/files/styles/scale_768_w/public/images/1_6_5_Neurogastronomie_download_0.jpg?itok=b7dWxHou)