The Anatomy of Fragrance

It couldn't be more direct: When a scent reaches the nose, it travels directly to the olfactory bulb in the brain. Here, various scent information is blended into an overall impression.

Scientific support: Prof. Dr. Frank Zufall, Prof. Dr. Marc Spehr

Published: 06.08.2018

Difficulty: intermediate

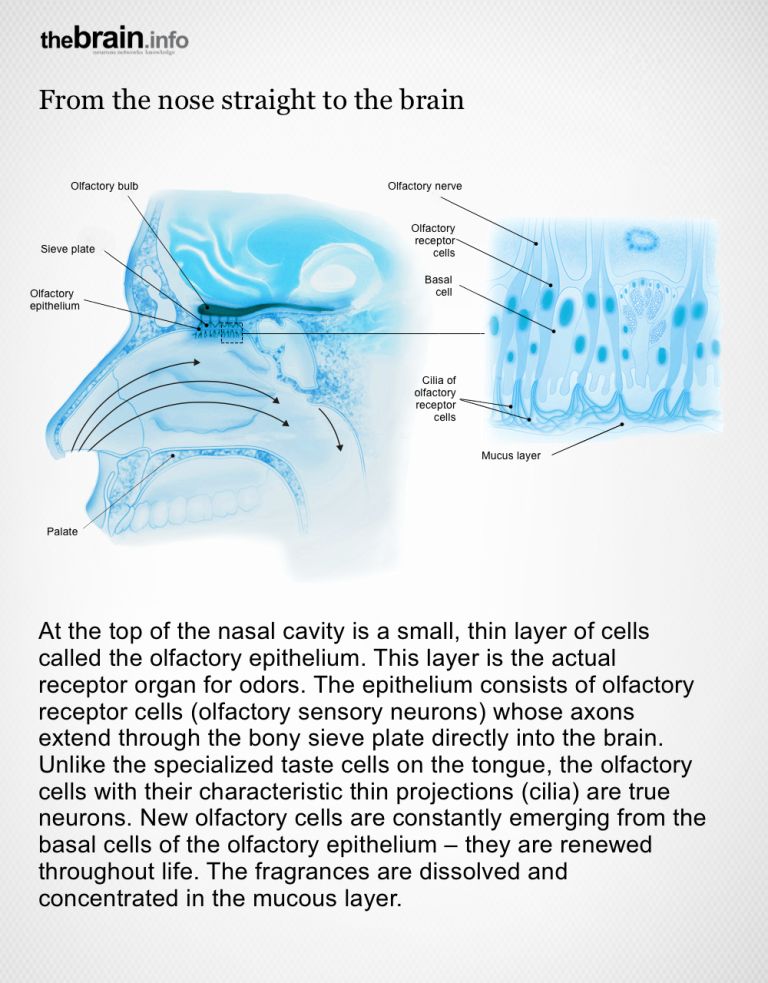

- Scent is composed of chemical molecules that attach themselves to the odor receptors of the olfactory cells in the Olfactory epithelium of the nasal cavity.

- The olfactory cells extend into the Olfactory bulb of the brain. The scent information therefore travels directly there.

- In the olfactory bulb, the scent information from many individual scent molecules is combined into an overall impression. This creates characteristic spatial activation patterns, known as sensory maps.

Olfactory epithelium

An area of olfactory cells measuring approximately 5 cm² located at the rear of the nasal septum. The axons (long, fiber-like extensions of nerve cells) of the olfactory cells form the olfactory nerve and travel through the ethmoid bone to the olfactory bulb.

Olfactory bulb

bulbus olfactorius

The anterior part of the brain that transmits information from the olfactory nerves to the olfactory brain (rhinencephalon) after initial processing via the olfactory tract.

In the animal world, sex is also a matter of Nose. Many vertebrates have a separate organ for this purpose, located in the olfactory system: the vomeronasal organ, also known as the “Jacobson's organ.” This is a separate, chemically sensitive region in the nasal cavity whose sensory cells are equipped with special odor receptors. The sensory cells of the vomeronasal organ are stimulated by pheromones, specific odor signals that serve as a means of communication. For example, they signal the hierarchical position of an animal or whether it is ready to mate. The information is then transmitted to the Hypothalamus via the accessory olfactory bulb.

In humans, the vomeronasal organ develops during embryonic development, but then regresses to a rudimentary remnant. In some people, the remnants of this organ can be seen as tiny indentations to the right and left of the nasal septum, which lead into a blind tube. In others, these openings are not found. The function of such an organ in humans is highly controversial – which does not mean that we are completely insensitive to scent messages: very young infants, for example, recognize their mother and her breast by smell. In addition, experiments in which women's cycles synchronize with those of other women based solely on imperceptible scent samples show that pheromones also have a certain effect in humans. A vomeronasal organ is obviously not necessary for this; the olfactory mucosa is sufficient.

Nose

nasus

The olfactory organ of vertebrates. In the nasal cavity, the air is cleaned by cilia, and in the upper area is the olfactory epithelium, which detects odors.

Hypothalamus

The hypothalamus is considered the center of the autonomic nervous system, meaning it controls many motivational states and regulates vegetative aspects such as hunger, thirst, and sexual behavior. As an endocrine gland (which, unlike an exocrine gland, releases its hormones directly into the blood without a duct), it produces numerous hormones, some of which inhibit or stimulate the pituitary gland to release hormones into the blood.In this function, it also plays an important role in the response to pain and is involved in pain modulation.

Mmm, what a wonderful smell – a piece of fresh bread, accompanied by a mature French cheese and a glass of dark red wine. The smell of food we like alone awakens our desire for it. It helps us to identify it, but also to recognize whether it is digestible or perhaps harmful to our health. Anything that smells rotten or like spoiled meat evokes disgust and warns us not to eat it. An unpleasant smell can also be a warning if there is danger in a room, for example if there is smoke in the air or a foul smell of feces.

The smell itself – whether pleasant or disgusting – is a chemical stimulus. It consists of small molecules in the air that encounter our olfactory organ when we inhale. Incidentally, this is not, as is often mistakenly assumed, the Nose. Rather, the nose is a gateway to the world of smell: when we inhale, it draws in air from the environment and transports it to the olfactory epithelium, a fine layer of cells at the top of the main nasal cavity. The human Olfactory epithelium measures around 10 square centimeters. This is comparatively small: dogs, for example, have up to 170 square centimeters, depending on the breed, and also have over 100 times more Receptor cells per square centimeter than Homo sapiens.

Nose

nasus

The olfactory organ of vertebrates. In the nasal cavity, the air is cleaned by cilia, and in the upper area is the olfactory epithelium, which detects odors.

Olfactory epithelium

An area of olfactory cells measuring approximately 5 cm² located at the rear of the nasal septum. The axons (long, fiber-like extensions of nerve cells) of the olfactory cells form the olfactory nerve and travel through the ethmoid bone to the olfactory bulb.

Receptor

A receptor is a protein, usually located in the cell membrane or inside the cell, that recognizes a specific external signal (e.g., a neurotransmitter, hormone, or other ligand) and causes the cell to trigger a defined response. Depending on the type of receptor, this response can be excitatory, inhibitory, or modulatory.

Three cell types for scent

The Olfactory epithelium consists mainly of three different cell types: in addition to the actual olfactory cells, there are supporting cells and basal cells, from which a constant supply of new olfactory cells matures. These cells only have a lifespan of a few weeks, then die and are replaced by new olfactory cells.

Contrary to what the name suggests, the supporting cells also play an important role in smelling. Among other things, they determine the composition of the mucus in which the scent molecules from the inhaled air dissolve before they reach the olfactory receptors. In addition, the mucus protects the brain from bacteria and viruses that could enter via the olfactory epithelium thanks to the antibodies it contains.

However, the main players are the olfactory cells, also known as olfactory Receptor neurons, which transmit odor information directly to the central nervous system (CNS). They have long, thin cilia at one end, which originate from a terminal thickening. The cilia are covered with odor receptors and protrude into the mucus of the olfactory epithelium. There, they come into contact with the scent molecules dissolved in it. When these molecules attach themselves to the odor receptors, Depolarization of the membrane occurs: positively charged sodium and calcium ions flow into the cell, while negatively charged chloride ions flow out. This changes the electrical properties of the cell. The chemical stimulus becomes an electrical one, which races through the Axon toward the CNS in the form of an action potential.

US researchers Linda Buck and Richard Axel, who were awarded the 2004 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their research on the olfactory system, discovered in 1991 that rats have more than 1,000 different genes for odor receptors. Each Gene encodes the blueprint for a receptor that differs from all other scent receptors and recognizes only very specific scent molecules. The human olfactory organ is less well equipped, with around 380 different functional receptor genes and a corresponding number of receptor types. The rest were lost in the course of evolution and are now only found in the genome in the form of non-functional pseudogenes.

Only one of these genes is expressed in each olfactory cell, so that the olfactory epithelium has a whole range of different sensory cells, each responsible for a small group of scent molecules.

Olfactory epithelium

An area of olfactory cells measuring approximately 5 cm² located at the rear of the nasal septum. The axons (long, fiber-like extensions of nerve cells) of the olfactory cells form the olfactory nerve and travel through the ethmoid bone to the olfactory bulb.

Receptor

A receptor is a protein, usually located in the cell membrane or inside the cell, that recognizes a specific external signal (e.g., a neurotransmitter, hormone, or other ligand) and causes the cell to trigger a defined response. Depending on the type of receptor, this response can be excitatory, inhibitory, or modulatory.

Depolarization

The decrease in membrane potential (towards 0 mV) from the resting potential, which is measured between the inside of the cell and the outside space and has a difference of -70 mV.

Axon

axon

The axon is the extension of the nerve cell that is responsible for conducting nerve impulses to the next cell. An axon can branch out many times, reaching a large number of downstream nerve cells. It can be more than a meter long. The axon ends in one or more synapses.

Gene

Information unit on DNA. Specialized enzymes translate the core component of a gene into ribonucleic acid (RNA). While some ribonucleic acids perform important functions in the cell themselves, others specify the order in which the cell should assemble individual amino acids into a specific protein. The gene thus provides the code for this protein. In addition, a gene also includes regulatory elements on the DNA that ensure that the gene is read exactly when the cell or organism actually needs its product.

Recommended articles

Direct line to the brain

The olfactory axons of all olfactory cells together form the olfactory nerve. However, unlike other nerve cells, they do not bundle together, but instead penetrate the cribriform plate, a fine porous layer of bone bordering the olfactory epithelium, as small groups of axons. From here, they continue to the two olfactory bulbs (bulbi olfactori, singular bulbus olfactorius), protrusions of the brain. The entry points into the olfactory bulbs are the glomeruli, spherical structures. In rats, each Olfactory bulb contains around 2,000 glomeruli – in humans, there are even more, although the exact number is unknown. This is where the primary olfactory neurons converge and transmit their odor information to the secondary olfactory neurons, the so-called mitral cells – strictly separated according to Receptor type. Each glomerulus therefore selectively receives information about a very specific type of odor molecule.

The mitral cells then sort the odor information and project it directly to the Olfactory cortex and several neighboring structures in the temporal lobe, including the emotional center, the Amygdala. The olfactory information then reaches downstream brain regions, which link the scent to emotions, pleasure, or motivational functions and store it in memory.

But how is it possible that only 380 genes can lead us into such a rich and diverse sensory world of scents? After all, humans also recognize an almost infinite variety of different smells. Nobel Prize winners Buck and Axel, as well as many other research groups, have contributed to finally solving this mystery: they have discovered that the olfactory bulb acts as a kind of mixing console where scent combinations are put together. This is referred to as the ensemble code.

Olfactory bulb

bulbus olfactorius

The anterior part of the brain that transmits information from the olfactory nerves to the olfactory brain (rhinencephalon) after initial processing via the olfactory tract.

Receptor

A receptor is a protein, usually located in the cell membrane or inside the cell, that recognizes a specific external signal (e.g., a neurotransmitter, hormone, or other ligand) and causes the cell to trigger a defined response. Depending on the type of receptor, this response can be excitatory, inhibitory, or modulatory.

Olfactory cortex

The olfactory cortex comprises the structures of the cerebrum that are responsible for processing olfactory information. The primary olfactory cortex is the prepiriform cortex, an evolutionarily ancient part of the cortex (paleocortex) with a three-layer structure.

Amygdala

corpus amygdaloideum

An important core area in the temporal lobe that is associated with emotions: it evaluates the emotional content of a situation and reacts particularly to threats. In this context, it is also activated by pain stimuli and plays an important role in the emotional evaluation of sensory stimuli. Inaddition, it is involved in linking emotions with memories, emotional learning ability, and social behavior. The amygdala is part of the limbic system.

Memory

Memory is a generic term for all types of information storage in the organism. In addition to pure retention, this also includes the absorption of information, its organization, and retrieval.

At the scent mixing console

Most natural scents are composed of several components. When we smell an apple, various molecules float through the air, combining to create this scent. They dock onto the corresponding receptors in the Olfactory epithelium and send the information to the associated glomeruli in the Olfactory bulb This creates characteristic spatial activation patterns, known as sensory maps. The scent of an apple clearly differs from the patterns for the scent of roses, vanilla crescent cookies, or the stench of rotten fish.

“The olfactory bulb creates a fingerprint for each smell, which is then processed in the higher regions of the brain,” explains Amir Madany, who studies odor Perception at the Institute for Neuro- and Bioinformatics at the University of Lübeck. “The olfactory bulb serves as an amplifier of olfactory information and synchronizes its individual components.” This is because when the scent of apples reaches the nose, the individual scent molecules do not dock onto the corresponding receptors at the same time. “The stimulus is kept active in the olfactory bulb for a while so that the brain can process the overall impression.”

Madany himself is working on olfactory maps of a completely different kind. He creates so-called perception maps. To do this, he has test subjects sniff different scent samples and describe them using a predefined list of words. Is the smell pleasant or unpleasant? Does it smell fruity? And if so, does it smell more like apple or banana? In this way, he was able to prove that around 30 factors are necessary to describe all the smell categories in which humans consciously perceive smells.

“First and foremost is the category ‘pleasant or unpleasant’, which allows a quick decision to be made about ‘edible or inedible’ – but that was already clear to the philosophers of antiquity,” he says with a laugh. Madany is fairly certain that the second category is “nutty” or “not nutty,” which also helps to locate certain food sources. However, a lot of research still needs to be done to establish a definitive ranking that covers all categories.

Olfactory epithelium

An area of olfactory cells measuring approximately 5 cm² located at the rear of the nasal septum. The axons (long, fiber-like extensions of nerve cells) of the olfactory cells form the olfactory nerve and travel through the ethmoid bone to the olfactory bulb.

Olfactory bulb

bulbus olfactorius

The anterior part of the brain that transmits information from the olfactory nerves to the olfactory brain (rhinencephalon) after initial processing via the olfactory tract.

Perception

The term describes the complex process of gathering and processing information from stimuli in the environment and from the internal states of a living being. The brain combines the information, which is perceived partly consciously and partly unconsciously, into a subjectively meaningful overall impression. If the data it receives from the sensory organs is insufficient for this, it supplements it with empirical values. This can lead to misinterpretations and explains why we succumb to optical illusions or fall for magic tricks.

First published on November 27, 2013

Last updated on July 3, 2025