Not just in the Mouth and Nose

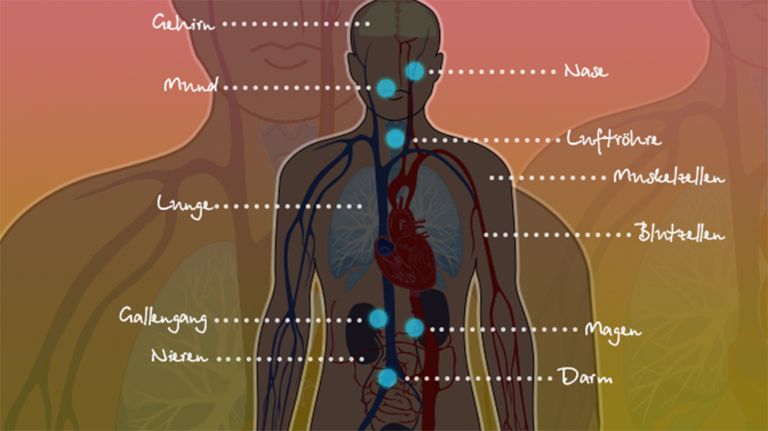

Taste and smell receptors are not only found in the mouth and nose. Researchers have discovered and continue to discover them in more and more places in the body – even in the brain. They are beginning to decipher their functions and hope to gain insights into the development of diseases.

Scientific support: Prof. Dr. Thomas Hummel, Prof. Dr. Hanns Hatt

Published: 02.09.2025

Difficulty: intermediate

- Taste and smell receptors are not only found in the mouth and nose.

- Researchers are finding them in more and more places in the body: in the skin and bronchi, blood and muscle cells, on sperm, and even in the brain.

- They are beginning to decipher their functions and hope to gain insights into the development of diabetes and other diseases.

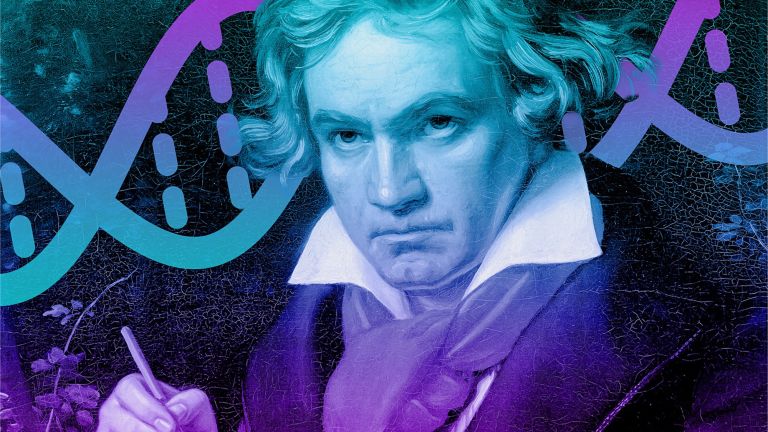

When Charles S. Zuker and Nicholas Ryba and their teams at Columbia and Washington Universities discovered the receptors for our five basic tastes ▸ The secret of taste perception, they had looked for them where it was most obvious: on the tongue. But now it is becoming increasingly clear that the tongue does not have a monopoly on taste receptors – just as olfactory receptors are not found only in the nose.

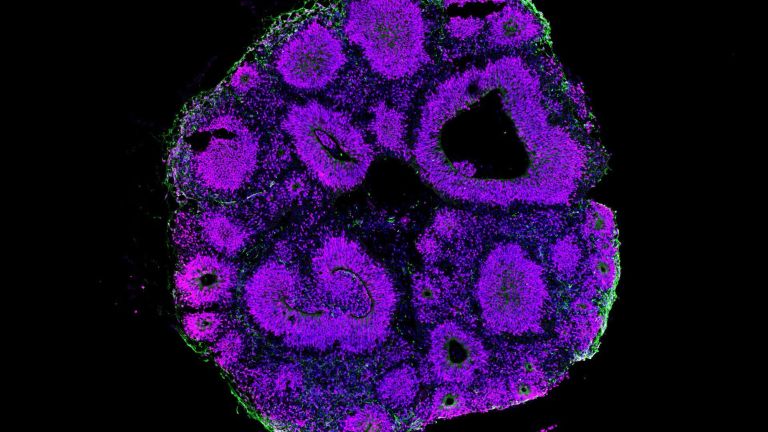

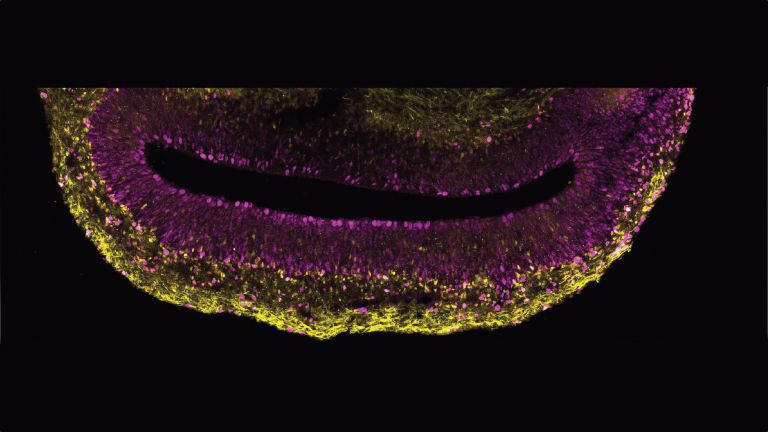

In 2003, Thomas E. Finger of the Rocky Mountain Taste and Smell Center at the University of Colorado discovered taste receptors in the noses of rats and mice, and later also in the noses of humans. Since then, discoveries have come thick and fast: Taste and smell receptors have been found in the respiratory tract, skin, heart, stomach, kidneys, intestines, muscle cells, brain, blood, and even sperm.

Tasting with the heart?

So does the heart taste the Sunday roast? Does the brain smell when we have eaten garlic, or do blood cells smell the apple pie we just ate? Do our muscles recoil when we bite into a rancid hazelnut?

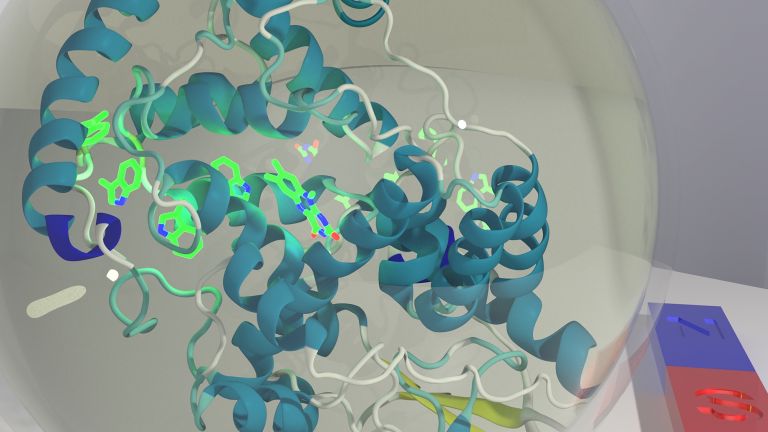

No. If the taste and smell receptors are not connected to the taste and smell centers of the brain, their activation does not lead to a taste or smell experience for humans. However, in parts of the body other than the tongue and nose, these receptors function as chemosensors in the same way as they do in the mouth and nose. They detect whether certain substances are present and then trigger specific reactions. Exactly which reactions depends on the system in which they are located. “Every cell needs to communicate with its environment, and this is done, among other things, by means of chemosensory perception,” explains Jörg Strotmann, professor at the Institute of Physiology at the University of Hohenheim. “Chemosensory perception is very old in evolutionary history; it can already be found in the nematode C. elegans. Apparently, nature has used its invention again and again.”

Researchers already have a good understanding of the function of some of these taste and smell receptors found in unusual locations, while for others they are testing hypotheses. However, there are also some where they are still completely in the dark. This much is known so far: Chemosensors can activate intracellular reaction cascades in organs that lead to the release of hormones or neurotransmitters, which in turn transmit signals to other parts of the body. Alternatively, chemosensors directly influence the physiological reactions of the cells on which they are located.

Thomas Finger was able to show that the bitter receptors in the mouse's nose react to foreign substances that have entered the airways, but also to metabolic products of bacteria that have settled in the nasal cavity. Once activated, the bitter receptors ensure that a substance is released into the surrounding tissue, triggering local inflammation – and thus also activating the immune system to fight off intruders and prevent harmful substances from penetrating deeper into the respiratory tract.

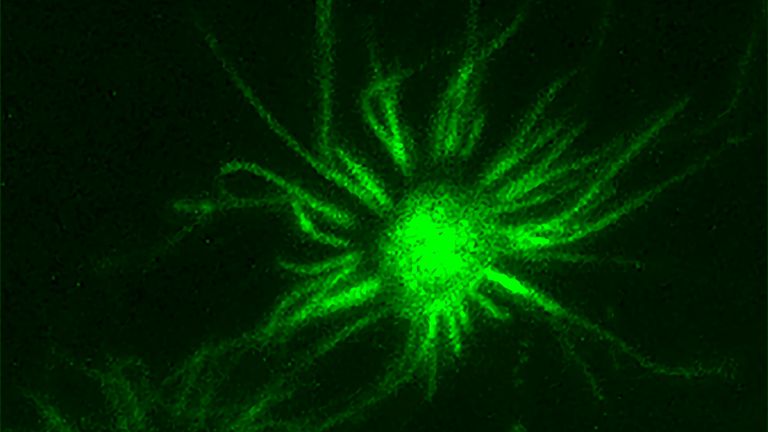

In cell cultures from the lower human airways, bitter receptors stimulate the cilia (tiny hairs) on the cell surface to move more vigorously when activated, which could serve to wash away substances from the cell surface that do not belong there. In another experiment, a scent reminiscent of apricots, when combined with smooth muscle cells from the human respiratory tract, caused them to relax. Whether this could be a promising approach to developing an asthma medication remains to be seen.

Scents everywhere

Other scent receptors are found in the heart, where they react to blood lipids and influence contraction strength and heart rate. There are ideas about how this could be used therapeutically in diabetics. In the intestine, scent receptors influence serotonin release: anise, clove, and caraway are therefore good for intestinal activity. And then there is an odor receptor in the skin that accelerates wound healing by up to 30 percent and extends the life of hair by up to 40 percent. The associated scent even smells good – it is reminiscent of sandalwood.

Certain receptors on sperm that react to a scent reminiscent of lily of the valley have made it into all media. However, it has not been proven whether sperm actually find their way to the egg in this way, as it is not clear where the scent actually comes from. In any case, sperm swim faster towards the scent. The function of at least seven other scent receptors, which are also found on sperm, is also unclear. However, it is known that the matching molecules are also found in female vaginal secretions.

Recommended articles

Umami receptors on sperm

We know more about an umami receptor on the sperm of mice and humans, which Ingrid Boekhoff and her team at the Walther Straub Institute for Pharmacology and Toxicology at Ludwig Maximilian University in Munich discovered. “We initially assumed that they help the sperm find their way to the egg,” reports the researcher. “But that has not been confirmed.” Instead, their findings point in a different direction: the head of the sperm contains a vesicle (bubble) filled with digestive enzymes. Contact with the egg causes these enzymes to be released and “digest” the egg's shell, allowing the sperm and egg to fuse. If the sperm loses this vesicle before it is near the egg cell, it can no longer fertilize the egg cell. “The umami receptor in the sperm appears to be involved in this,” reports Boekhoff. The researchers were able to show that mouse sperm without the receptor are more likely to lose this vesicle – even without contact with the egg cell.

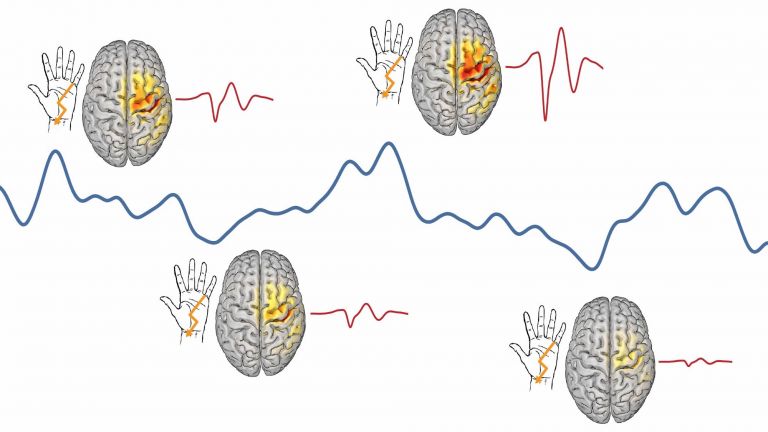

The role of sweet and umami receptors in the digestive tract is also well understood. When food rich in sugar or glutamate enters the stomach, these receptors cause a hormone to be released that stimulates the appetite. As they pass through the intestine, sweet substances are registered by receptors in cells of the intestinal mucosa, which then produce incretins – hormones that in turn stimulate the release of insulin. The faster this happens, the more insulin is produced. The sugar is then absorbed from the bloodstream by various tissues.

The taste receptors in the digestive tract may also provide an explanation for a long-known effect: Sugar absorbed through food activates insulin production much more strongly than sugar absorbed through the bloodstream.

Sweet only describes the surface

Understanding these relationships could be of great importance for the treatment of diabetes, suspects Anthony Sclafani of the City University of New York. “The fact that we like a food because it is sweet only describes the surface,” explains Strotmann. This is because what happens to food in the body depends on the fine control of the digestive system. This is where decisions are made about how much gastric juice is produced or how strongly the intestines move. If there are problems with the receptors in this part of the digestive system, this could lead to malfunctions. This could result in the absorption of far too much glucose, which could play a role in diabetes. “Above all, however, the connection between such malfunctions and obesity is currently being discussed,” reports Strotmann. He is convinced: “Understanding the role of these newly discovered receptors is a highly important step toward understanding food intake.”

When activated, bitter receptors in the large intestine trigger a feeling of satiety, or they release anions that attract water and thus cause diarrhea—perhaps to protect against the intrusion of toxic substances, which often taste bitter. The olfactory receptors in the kidney influence blood pressure.

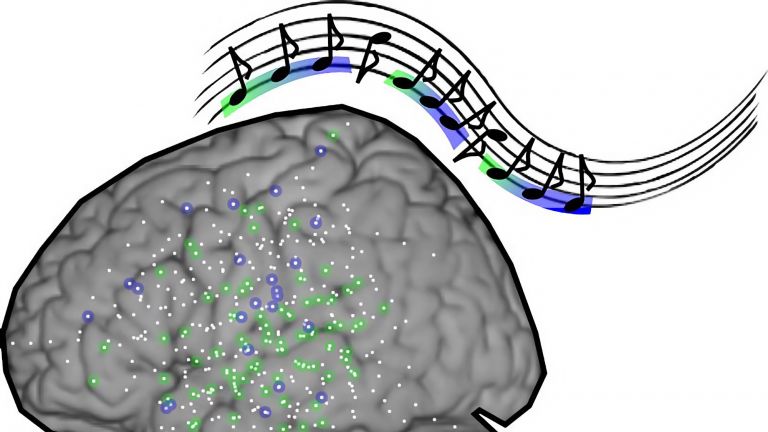

The function of odor receptors in certain regions of the brain, on the other hand, is still completely mysterious. “To this day, no one understands how the nervous system controls all the functions of the organism. And now these receptors come into play, which obviously no one had on their list, but which certainly play a role,” says Strotmann, excited about the emerging field of research.

Identification by gene sequence

And how do you find receptors in such unusual places? Sometimes researchers look for them, sometimes they find them by chance: for example, when they look at the products of transcription processes, the reading processes of DNA, in a cell and encounter patterns that they recognize from tissues of the tongue or nose. The genetic coding also tells them whether they are dealing with an odor or taste detector. Since the receptors do not produce either odor or taste, it is not possible to distinguish between them on that basis. Another criterion also fails: in the nose, the odor receptors react to molecules in the air we breathe, while the taste receptors react to molecules dissolved in chewed food. Inside the body, however, there are only dissolved molecules. This means that the receptors cannot be distinguished based on whether they react to volatile or dissolved molecules. The only option is to look at the gene sequence.

“Imagine if the olfactory receptors had first been found in the kidneys. Researchers today would be wondering why we have receptors from the kidneys in our noses,” says Strotmann, amused by the confusion over terminology. Meanwhile, the chemosensors that are found where they were not expected to be also have their own name—at least when it comes to scents: “Extra-nasal olfactory receptors” – as opposed to the well-known “olfactory receptors” (OR).

Further reading

- Finger TE, Kinnamon SC: „Taste isn’t just for the buds anymore“, F1000 Biology Reports 2011, 3:2 (zum Abstract).

- Arbeitsgruppe von Ingrid Boekhoff; URL: http://www.wsi.med.uni-muenchen.de/forschung/allg_pharma_toxi/boekhoff/index.html [Stand: 10.10.2013], zur Webseite.

- Thomas E. Finger Lab; URL: http://www.ucdenver.edu/academics/colleges/medicalschool/centers/tastesmell/Pages/TFingerLab.aspx [Stand: 10.10.2013], zur Webseite.

First published on November 27, 2013

Last updated on December 2, 2025