Fragrant Brands

Room fragrance for a hotel, scent for a jeans brand, soothing smells on the train: marketing experts want to seduce customers through their sense of smell. They know that this awakens emotions – and increases sales.

Scientific support: Prof. Dr. Frank Zufall, Prof. Dr. Marc Spehr

Published: 03.07.2025

Difficulty: intermediate

- Business economists rely on scents in marketing. In hotels, supermarkets, and boutiques, specially created fragrances are used to attract customers.

- Economists rely on findings from neuroscience: scents directly influence the Limbic system – and thus Emotions and memory.

- Marketing experts have proven that the use of scents can increase sales.

- The University of Munich conducted an experiment in collaboration with Deutsche Bahn: customer satisfaction was higher on a regional train when a calming scent was diffused.

Limbic system

The limbic system is a functional unit in the brain. It consists of interconnected structures, primarily in the cerebrum and diencephalon. The structures assigned to the system vary depending on the source, but the most important components are the hippocampus, amygdala, cingulate gyrus, septum, and mammillary bodies. The limbic system is involved in autonomic and visceral processes as well as in mechanisms of emotion, memory, and learning. Some authors mistakenly reduce the limbic system to the emotional world by referring to it as the "emotional brain."

Emotions

Neuroscientists understand "emotions" to be complex response patterns that include experiential, physiological, and behavioral components. They arise in response to personally relevant or significant events and generate a willingness to act, through which the individual attempts to deal with the situation. Emotions typically occur with subjective experience (feeling), but differ from pure feeling in that they involve conscious or implicit engagement with the environment. Emotions arise in the limbic system, among other places, which is a phylogenetically ancient part of the brain. Psychologist Paul Ekman has defined six cross-cultural basic emotions that are reflected in characteristic facial expressions: joy, anger, fear, surprise, sadness, and disgust.

Memory

Memory is a generic term for all types of information storage in the organism. In addition to pure retention, this also includes the absorption of information, its organization, and retrieval.

An exquisite scent not only helps to market a product, but also adorns the individual – at least that is what people believe, and they spend a lot of money on fragrances. According to Statista, global sales of perfumes and eaux de toilette amounted to around 53.9 billion euros in 2023. In Germany alone, the figure was 1.3 billion. Women's fragrances are clearly in the lead.

But it's not just perfumes that generate sales for cosmetics manufacturers thanks to their pleasant scent. Fragrance is also an important selling point for deodorants, soaps, aftershaves, and shower gels. In addition, the Nose is likely to play a role in deciding what skin creams, shampoos, or shaving foams are purchased. Then there are scouring creams, detergents, and room fragrances – all products where the sense of smell plays a major role. In 2023, drugstore and perfumery retailers in Germany generated a total turnover of around 25.7 billion euros.

Nose

nasus

The olfactory organ of vertebrates. In the nasal cavity, the air is cleaned by cilia, and in the upper area is the olfactory epithelium, which detects odors.

There's that smell. As if a perfumed woman had just walked by. It's everywhere in the spacious hotel lobby: in front of the elevators, in the reading corner, by the armchairs in the covered atrium. Floral, fresh, sweet, yet unobtrusive. It is particularly noticeable directly in front of the reception desk. A glance upwards reveals why: there are the grilles of the ventilation system. Fresh air flows into the room here – and with it the scent molecules.

It is a fragrance that the Swissôtel chain developed especially for its Berlin hotel. “A touch of alpine flowers and real gentian” as well as “slender light woods in the background” are intended to embody “Swiss precision” and create a “feel-good atmosphere,” writes the hotel. Every Swissôtel worldwide has its own room fragrance. The basic scent is always the same, with variations adapted to each city. For Berlin, for example, the scent of lime blossom is added.

The hotel illustrates a trend: companies now like to use scents to bind customers to their brand. Business economists call this “scent marketing.” This is because managers have now also become aware of findings in neuroscience (the umbrella term for this is actually “neuromarketing”).

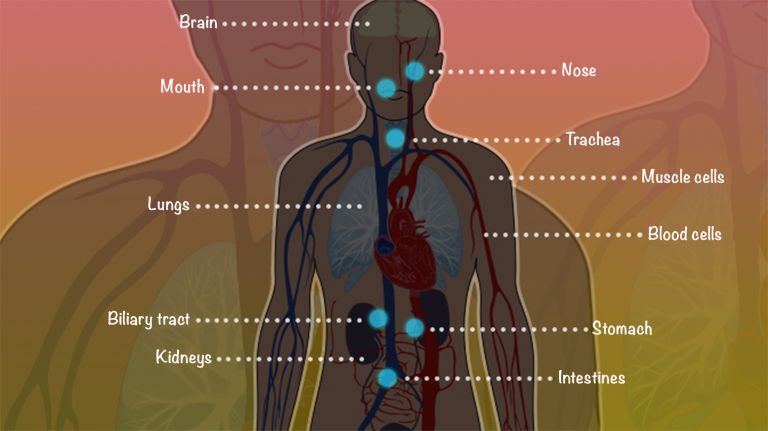

Brain researchers have long known that scents influence feelings and memories much more directly than the other senses. They have an immediate effect on the limbic system, which controls our Emotions. And events that are associated with strong feelings are much more likely to stick in our Memory. Everyone has experienced how smells can bring back memories; for example, when a certain soap suddenly transports you back to the comfort of your grandmother's house.

The US fashion company Abercrombie & Fitch makes particularly striking use of this effect. A sweet scent is sprayed in large quantities in the stores, so that you can smell it even outside the store. All garments are also perfumed with it. The result: the scent is now perceived as part of the brand. In tests, young people immediately associated jeans with Abercrombie & Fitch – regardless of the cut of the pants, simply because they exuded the scent of the brand.

Emotions

Neuroscientists understand "emotions" to be complex response patterns that include experiential, physiological, and behavioral components. They arise in response to personally relevant or significant events and generate a willingness to act, through which the individual attempts to deal with the situation. Emotions typically occur with subjective experience (feeling), but differ from pure feeling in that they involve conscious or implicit engagement with the environment. Emotions arise in the limbic system, among other places, which is a phylogenetically ancient part of the brain. Psychologist Paul Ekman has defined six cross-cultural basic emotions that are reflected in characteristic facial expressions: joy, anger, fear, surprise, sadness, and disgust.

Memory

Memory is a generic term for all types of information storage in the organism. In addition to pure retention, this also includes the absorption of information, its organization, and retrieval.

Supermarkets with scent dispensers

A scent test in a randomly selected supermarket in Berlin-Neukölln, Rewe on Treptower Straße. The sliding door opens and immediately there is the smell of fresh bread rolls, because to the left of the entrance is a baker's stand where the rolls are baked in the oven behind the counter. In the world of marketing, it is well known that the smell of freshly baked goods is associated with pleasant memories for almost every customer and therefore lifts their mood. Retailers make deliberate use of this effect when designing their stores. In the aisles of the supermarket, on the other hand, there is hardly any input for the Nose. A hint of lemon and grapefruit in the fruit and vegetable section – and the coffee shelf is impossible to miss, as there is a grinding machine. There is an unpleasant sour and fermented smell in the corner with the deposit machines.

If the supermarket were in the US, the nose would probably get a lot more pleasant impressions: the fruit smells of oranges, the aroma from the fish counter is masked by the scent of herbs, and the smell of chocolate wafts from the candy section. None of these scents come from the products themselves, but rather from dispensers or the ventilation system, with the aim of putting customers in a pleasant mood. Then they stay longer and are also willing to buy more. “The targeted use of scents is not common in German supermarkets,” says Robert Müller-Grünow. His company, Scentcommunication, specializes in scent marketing. “The German retail sector is relatively conservative.” A response from Rewe to an inquiry from dasgehirn.info showed that the company is apparently afraid of being accused of manipulation. The company wrote: “The use of scents plays no role in our stores or in the design of our stores. We simply do not use such things.”

The supermarket Edeka is more open about the issue. A new concept is being tested in a store in Bienenbüttel in the Lüneburg Heath. All the senses are to be addressed in order to entice customers to linger: feel-good music comes from the loudspeakers, small samples are available to Taste in many places, and wood laminate makes walking more comfortable than the usual tiles. In addition, dispensers on the ceiling emit a fragrance blend of rosewood, orange, and lavender. This is intended to put customers in a pleasant mood. With success: visitors find the store, which has been furnished in this way, to be very high-quality and pleasant – and also spend more money. The industry magazine Lebensmittelzeitung reported a 40 percent increase in sales.

Nose

nasus

The olfactory organ of vertebrates. In the nasal cavity, the air is cleaned by cilia, and in the upper area is the olfactory epithelium, which detects odors.

Taste

The sensory impression we refer to as "taste" results from the interaction between our senses of smell and taste. In terms of sensory physiology, however, "taste" is limited to the impression conveyed to us by the taste receptors on the tongue and in the surrounding mucous membranes. It is currently assumed that there are five different types of taste receptors that specialize in the taste qualities sweet, sour, salty, bitter, and umami. In 2005, scientists also identified possible taste receptors for fat, whose role as a distinct taste quality is still being investigated.

Recommended articles

A cloud of manipulation

Not everyone is equally susceptible to the seductive power of scents. In 2005, marketing scientist Maureen Morrin from Rutgers University in New Jersey conducted a study in a shopping center to investigate how different types of shoppers react to manipulation. People who tend to make impulsive purchasing decisions are not particularly responsive to scents. They respond primarily to music in the store. People who think carefully before spending money are different: they are largely immune to the ostensibly noticeable stimulus of music – but scents, which have a more subtle effect, were more likely to persuade them to make a purchase.

Robert Müller-Grünow went one step further in the US: he managed to evoke pleasant memories to boost sales. The Coca-Cola Company had asked him to find a scent for their supermarket sales areas. “They wanted a fragrance that would evoke a feeling of lightness in customers,” recalls Robert Müller-Grünow. He found what he was looking for: the scent of a sunscreen that was particularly popular in the USA in the 1960s was a perfect fit. Supermarket visitors passing by the cola shelves could smell it. It reminded many people of summer, the beach and their childhood – their mood lifted, and some added another bottle of soda to their shopping cart.

Jasmine scent on the regional train

Marketing experts from Ludwig Maximilian University in Munich wanted to know whether scents could also help Deutsche Bahn improve its image. To find out, they conducted an experiment on a regional train on the Augsburg-Lindau route, in collaboration with Robert Müller-Grünow's company. In one carriage, they used the air conditioning system to diffuse a scent of jasmine, rosewood, and melon. These are all aromas that are said to have a calming effect. “The scent was very subtle; you only noticed it if you smelled it closely,” recalls business economist Anna Girard, who was involved in the experiment on behalf of the university. The other carriage was not scented for comparison purposes. “The result totally surprised the railway company,” says Anna Girard. Passengers in the scented carriage rated both the quality and the experience of the train journey significantly better – and they rated the Deutsche Bahn brand more positively. In a follow-up study, trains were delayed due to the onset of winter – yet the test subjects did not rate the journey any worse.

On the one hand, this is good for the railway company – on the other hand, it could be seen as manipulation intended to conceal shortcomings. Practitioner Robert Müller-Grünow does not see it that way: “There is always some kind of smell in a train compartment – from fellow passengers or cleaning products. If you improve the smell to make customers feel more comfortable, it's like making the seats more comfortable: you improve the travel experience.” Scientist Anna Girard is more cautious. She also sees the positive effect of scents. However, she notes that companies should communicate openly about the use of scents – especially when they are used subtly at the threshold of perception.

Perception

The term describes the complex process of gathering and processing information from stimuli in the environment and from the internal states of a living being. The brain combines the information, which is perceived partly consciously and partly unconsciously, into a subjectively meaningful overall impression. If the data it receives from the sensory organs is insufficient for this, it supplements it with empirical values. This can lead to misinterpretations and explains why we succumb to optical illusions or fall for magic tricks.

Further reading

- Morrin, M: Person-Place Congruency: The Interactive Effects of Shopper Style and Atmospherics on Consumer Expenditures. In: Journal of Service Research 2005;8(2):181 – 191 (zum Abstract).

- Girard, M et al: Markenduft als Treiber der Service Experience. In: Marketing Review St. Gallen 2013 (Dezember) (zum Abstract).

First published on November 27, 2013

Last updated on July 3, 2025