Smell and Taste – often underestimated

The smell of coffee invigorates us. We sometimes crave sweet or salty foods, are repelled by bitter tastes, and certain smells trigger nostalgic memories: our senses of smell and taste have more power over us than we often realize.

Scientific support: Prof. Dr. Hanns Hatt

Published: 06.09.2025

Difficulty: easy

- Our senses of smell and Taste have a long evolutionary history: reacting to chemical substances in the environment is important even for single-celled organisms.

- Our chemical senses are unusually direct and strongly connected to centers in the brain that are responsible for basic needs such as hunger and thirst, emotions, and memories. Their influence on our well-being is correspondingly great.

- Thanks to a multitude of different receptors in the nose, we can distinguish between thousands of smells; in contrast, according to current knowledge, there are only five basic tastes. However, the sense of smell is also crucial for the taste experience: food aromas travel directly from the oral cavity to the olfactory mucosa in the nose.

- Thanks to the direct connection between the olfactory system and the hippocampus, smells can evoke vivid memories. Even if we are not consciously aware of them, they can influence our emotional state.

- The main function of the sense of taste is to inform us about the nutritional value and possible dangers of food, which is why we have an innate preference for sweet things and an aversion to bitter things. However, taste preferences can change throughout our lives as a result of experience and habit, which is why they vary so much from person to person.

Taste

The sensory impression we refer to as "taste" results from the interaction between our senses of smell and taste. In terms of sensory physiology, however, "taste" is limited to the impression conveyed to us by the taste receptors on the tongue and in the surrounding mucous membranes. It is currently assumed that there are five different types of taste receptors that specialize in the taste qualities sweet, sour, salty, bitter, and umami. In 2005, scientists also identified possible taste receptors for fat, whose role as a distinct taste quality is still being investigated.

Nose

nasus

The olfactory organ of vertebrates. In the nasal cavity, the air is cleaned by cilia, and in the upper area is the olfactory epithelium, which detects odors.

6:30 a.m.: The alarm clock rings. Unsteady, clumsy steps lead to the kitchen, where hands almost automatically find the filter bag, coffee can, and switch. Shortly thereafter, a promising scent reaches the Nose – the aroma of freshly brewed coffee. The circulation gradually gets going, the head clears, and the mood lifts.

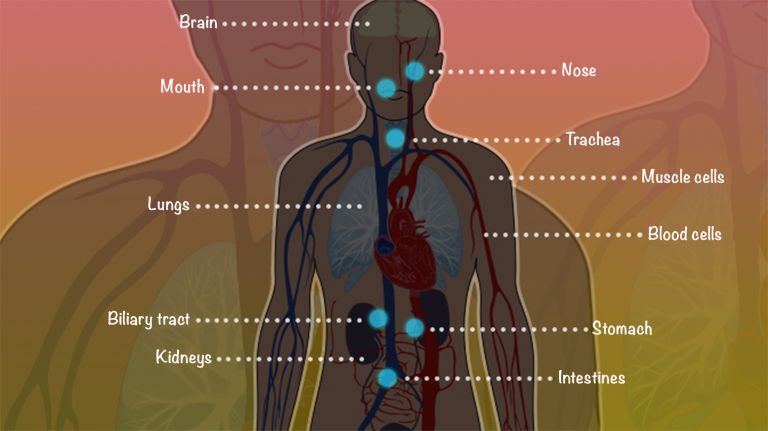

It is not only light, sound, and direct touch that humans – and animals – can perceive through their sensory organs. Much older in evolutionary terms is an ability that is already useful for single-celled organisms: the ability to register certain chemical substances in the environment. This is possible because molecules or ions dock onto special Receptor cells, triggering a signal cascade.

In humans, the senses of smell and Taste work according to this principle: on the one hand, there are volatile substances that enter the nasal cavity via the air we breathe and cause receptor cells in the olfactory mucosa to send signals to the brain; on the other hand, there are components of food that trigger nerve impulses via taste receptors in the mouth and throat.

Nose

nasus

The olfactory organ of vertebrates. In the nasal cavity, the air is cleaned by cilia, and in the upper area is the olfactory epithelium, which detects odors.

Receptor

A receptor is a protein, usually located in the cell membrane or inside the cell, that recognizes a specific external signal (e.g., a neurotransmitter, hormone, or other ligand) and causes the cell to trigger a defined response. Depending on the type of receptor, this response can be excitatory, inhibitory, or modulatory.

Taste

The sensory impression we refer to as "taste" results from the interaction between our senses of smell and taste. In terms of sensory physiology, however, "taste" is limited to the impression conveyed to us by the taste receptors on the tongue and in the surrounding mucous membranes. It is currently assumed that there are five different types of taste receptors that specialize in the taste qualities sweet, sour, salty, bitter, and umami. In 2005, scientists also identified possible taste receptors for fat, whose role as a distinct taste quality is still being investigated.

Always emotionally charged

The sense of smell, probably the oldest of our senses in terms of evolutionary development, also plays a special role anatomically: unlike sight, hearing, touch, and taste, it bypasses the thalamus, and its information arrives directly in the Amygdala and Frontal lobe ▸ The anatomy of scent. This is why smells are always emotionally charged for us: we perceive them as pleasant or repulsive, calming, disgusting, or invigorating...

6:41 a.m.: The dog, who was already waiting excitedly with his tail wagging when the kitchen door opened, now has to get his due. On his walk around the block, he sniffs the corners of houses, lampposts, and car tires as if there were nothing more important in the world.

The capabilities of the human sense of smell are astonishing: with around 20 million olfactory cells on ten square centimeters of mucous membrane, each carrying a single one of a total of around 400 different types of odor receptors, it can distinguish between many thousands, probably even tens of thousands, of scents. And in order to perceive a smell at all, it is sometimes sufficient for there to be a single scent molecule per trillion air molecules.

However, many other mammals rely much more on their sense of smell; they behave largely “following their nose,” while for humans, in many situations, the eyes and ears provide the decisive information. Accordingly, animals far surpass humans in terms of olfactory performance: some dogs, for example, have an olfactory mucosa that is more than ten times larger with correspondingly more cells, and the number of Receptor types is also significantly greater at just under 1,000. Where humans can no longer smell anything, extremely low concentrations of scent molecules still speak volumes to a dog: at a lamppost, it can not only smell that another dog was there, but also when, and draw conclusions about its physical condition. Trained sniffer dogs can do much more than that ...

7:24 a.m.: Warm water pours out of the shower, runs over the body, washing away the soap suds and with them the nighttime odors, the smell of bed and sweat. What remains is the fresh scent of shower gel, soon to be complemented by the slightly more intense scent of deodorant.

We perceive body odors as something intimate, animalistic, sometimes even unsavory. We fight against them with all possible means, trying to eliminate them as far as possible and cover them up with socially acceptable scents. Of course, this has more to do with cultural influences than with the fundamental predispositions of Homo sapiens: In earlier times, biological individual scents were sometimes much more highly valued, and some ethnic groups living close to nature do not even consider the smell of feces to be unpleasant.

Amygdala

corpus amygdaloideum

An important core area in the temporal lobe that is associated with emotions: it evaluates the emotional content of a situation and reacts particularly to threats. In this context, it is also activated by pain stimuli and plays an important role in the emotional evaluation of sensory stimuli. Inaddition, it is involved in linking emotions with memories, emotional learning ability, and social behavior. The amygdala is part of the limbic system.

frontal

An anatomical position designation – frontal means "towards the forehead," i.e., at the front.

Frontal lobe

Lobus frontalis

The frontal cortex is the largest of the four lobes of the cerebral cortex and its functions are correspondingly comprehensive. The front area, known as the prefrontal cortex, is responsible for complex action planning (known as executive functions), which also shapes our personality. Its development (myelination) takes up to 30 years and even then is not yet complete. Other important components of the frontal cortex are Broca's area, which controls our ability to express ourselves linguistically, and the primary motor cortex, which sends movement impulses throughout the body.

Receptor

A receptor is a protein, usually located in the cell membrane or inside the cell, that recognizes a specific external signal (e.g., a neurotransmitter, hormone, or other ligand) and causes the cell to trigger a defined response. Depending on the type of receptor, this response can be excitatory, inhibitory, or modulatory.

Recommended articles

Telltale body odor

The fact is that our smell reveals far more about us than we are normally aware of: Not only does it vary from person to person like a fingerprint, but it also reveals a lot about our state of mind and health. Dogs, for example, can smell whether their human counterpart is afraid, and with special training they can sniff out certain types of cancer or, in diabetics, dangerously high blood sugar levels. Humans are also capable of such perceptions, at least in a rudimentary form: Researchers at the Monell Chemical Senses Center in Philadelphia, USA, have proved that people evaluate images of women differently depending on whether the sweat they smelled at the same time was caused by stress or purely physical exertion.

12:45 p.m.: In the cafeteria today, after a brief gag reflex at the sight of the fish dish, the spelt patty wins the race. And a chocolate bar is purchased for later in the day.

Compared to the sense of smell, the sense of Taste seems rather spartan: according to current knowledge, our oral mucosa has receptors for just five basic tastes. Sweet, salty, sour, bitter, and the full-bodied, savory “umami” (Japanese for delicious) – and, of course, various combinations thereof: taste buds cannot distinguish between any more than that. The fact that food is by no means boring is because taste is much more than what our sense of taste conveys. The English language is very precise here, distinguishing between taste and flavor: while “taste” stands for the pure five-dimensional taste sensation, “flavor” describes the much more differentiated overall impression. This impression is primarily influenced by information from the sense of smell, because volatile substances from food enter the Nose from behind, so to speak, via the throat, and have a decisive influence on our taste Perception. But information such as temperature, consistency, and pain also play a role in “flavor”. ▸ The secret of the taste experience and ▸ Neurogastronomy – the new science of taste.

The sense of taste is also unusually strongly connected to regions of the brain that are responsible for basic needs, emotions, and certain reflexes. This is not surprising, given that eating and drinking sufficiently and appropriately has a decisive influence on the health and vitality of our bodies. Accordingly, the desire for sweet things is innate: This taste sensation is usually triggered by foods that are rich in carbohydrates and therefore high in energy. Umami is also unreservedly positive, as it stands for protein-rich food (as long as we don't deceive ourselves with flavor enhancers). A real craving for salty foods can arise when the body lacks essential minerals.

Taste

The sensory impression we refer to as "taste" results from the interaction between our senses of smell and taste. In terms of sensory physiology, however, "taste" is limited to the impression conveyed to us by the taste receptors on the tongue and in the surrounding mucous membranes. It is currently assumed that there are five different types of taste receptors that specialize in the taste qualities sweet, sour, salty, bitter, and umami. In 2005, scientists also identified possible taste receptors for fat, whose role as a distinct taste quality is still being investigated.

Nose

nasus

The olfactory organ of vertebrates. In the nasal cavity, the air is cleaned by cilia, and in the upper area is the olfactory epithelium, which detects odors.

Perception

The term describes the complex process of gathering and processing information from stimuli in the environment and from the internal states of a living being. The brain combines the information, which is perceived partly consciously and partly unconsciously, into a subjectively meaningful overall impression. If the data it receives from the sensory organs is insufficient for this, it supplements it with empirical values. This can lead to misinterpretations and explains why we succumb to optical illusions or fall for magic tricks.

Useful taste aversions

Sour and bitter tastes, on the other hand, are more ambivalent and are rejected by infants, for example. This also makes sense: sour foods may be unripe or spoiled, and many substances that are toxic to us Taste bitter. If we nevertheless develop a taste for sour apples or coffee in the course of our lives, this has to do with Habituation effects. In general, nutritional psychologists assume that what we like and dislike depends largely on habituation. This individual conditioning begins in the womb. Odors and flavors reach the developing senses of the fetus via the amniotic fluid. However, preferences can also suddenly reverse: if we feel sick after a certain meal, we may develop a real aversion to that food and its smell. This also works with animals, and we can use it to our advantage: if we feed wolves or coyotes sheep meat bait laced with a nauseating drug, they will lose their appetite for sheep.

5:13 p.m.: On the way home, the smell of fresh plum cake wafts from an open window – and suddenly, a vivid and real Memory comes to mind of how the little boy once stared into his grandmother's oven and watched impatiently as the plums on the yeast dough baked ...

The olfactory cells are also well connected to the hippocampus, a center of the brain that is important for memory. This ensures that certain aromas can literally send us on a journey back in time by evoking particularly detailed memories of situations we have experienced in the past. This mechanism has its own name, which it owes to the writer Marcel Proust: his novel “In Search of Lost Time” describes such a mental journey through time, triggered by a madeleine (a French sponge cake) dipped in tea – which is why it is referred to as the “madeleine effect.”

8:50 p.m.: The two-year-old son falls asleep contentedly with his teddy bear in his arms – now the parents can enjoy a little more intimate time together...

The Nose can convey a sense of security and closeness. Studies have shown that babies and mothers can identify each other by smell from birth. Many toddlers can hardly fall asleep without the familiarity conveyed by the scent of their favorite cuddly toy. Smell also plays a role in attracting partners and choosing a mate, even if not all the details have been clarified and the influence is probably much less significant than in the animal kingdom.

In summary, even though seeing, hearing, and feeling usually play a greater role in our conscious perception, smell and taste often have a decisive influence on our decisions ▸ Fragrant brands and on our well-being. This has been shown by many specific studies: for example, lavender and orange aromas can alleviate fear of the dentist. And we tend to have more pleasant dreams when we smell roses in our sleep than when we are tormented by the smell of rotten eggs. But our own experience will also confirm this if we consciously smell and taste more often in everyday life.

Taste

The sensory impression we refer to as "taste" results from the interaction between our senses of smell and taste. In terms of sensory physiology, however, "taste" is limited to the impression conveyed to us by the taste receptors on the tongue and in the surrounding mucous membranes. It is currently assumed that there are five different types of taste receptors that specialize in the taste qualities sweet, sour, salty, bitter, and umami. In 2005, scientists also identified possible taste receptors for fat, whose role as a distinct taste quality is still being investigated.

Habituation

If stimuli are repeatedly presented without having any effect, habituation to these stimuli occurs. This weakens the response and, over time, it disappears completely.

Memory

Memory is a generic term for all types of information storage in the organism. In addition to pure retention, this also includes the absorption of information, its organization, and retrieval.

Nose

nasus

The olfactory organ of vertebrates. In the nasal cavity, the air is cleaned by cilia, and in the upper area is the olfactory epithelium, which detects odors.

First published on November 27, 2013

Last updated on September 6, 2025