Man on the Move

Our bodies are constantly in motion, which we take for granted. But behind all our activities lies the perfect interplay between the motor systems in the brain, spinal cord, and about 650 muscles that control them.

Scientific support: Prof. Dr. Hansjörg Scherberger

Published: 01.12.2025

Difficulty: easy

- The perfect interplay between the brain, spinal cord, and the more than 650 muscles in the human body gives us complex motor skills.

- Movement sequences are planned and initiated by the motor centers in the brain.

- Motor signals are transmitted to the muscles via the spinal cord Sensory feedback helps to coordinate the successful execution of the movements.

- Once learned, many movements are performed unconsciously and automatically.

The sound of powerful footsteps reaches the spectator stands. The players rush across the red clay of the tennis court – left, right, forward toward the net, back to the baseline. Their eyes are focused on the small ball, which changes sides at impressive speed. Suddenly, a precise backhand right to the sideline, an energetic smash – and the match is over.

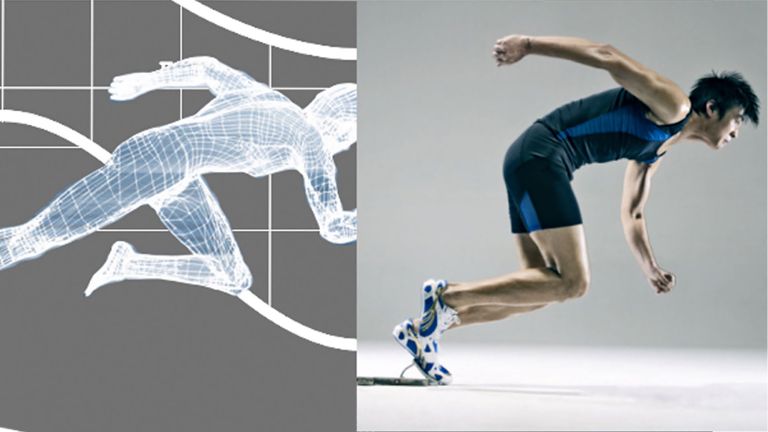

When laypeople watch professional athletes compete, they are often amazed by the precision and power of their movements. In doing so, they sometimes forget that they themselves perform remarkable feats countless times every day. Even simple tasks such as walking, lifting a shopping bag, or writing a letter require the complex interaction of various muscles and muscle groups, which tense and relax in precisely coordinated timing. And that's not all: in order for your hand and fingers to actually write your name at the end of a sequence of movements, your intention and execution must be precisely coordinated. ▸ Movement Planning: Reaching your Goal with Tactics

650 muscles ensure movement

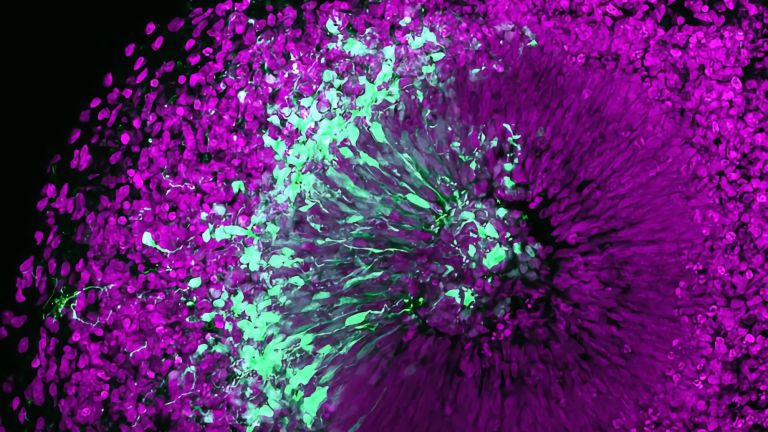

Compared to language or learning ability, motor skills are often an underestimated human achievement. Because many movements are unconscious or have become automatic over the course of our lives, we give little thought to the processes behind them. However, anyone who has ever watched a toddler learning to walk, or remembers their own first lessons on a bicycle or piano, will have an idea of the actual complexity of many of the movements we perform so effortlessly. The number of muscles in our body alone speaks for itself: a total of 650 are responsible for moving a human being, with around 30 of these involved in facial expressions alone. And in the brain, too, a large part of the cortex is associated with the control of motor functions. ▸ Command center for movement

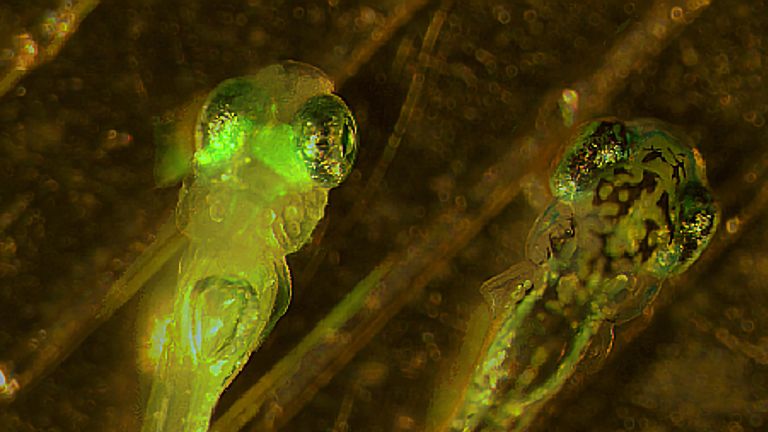

Without the targeted movement of muscles, we would not be able to survive. It is not only our arms, legs, and hands that are controlled by bundled muscle cells. The movements of our eyes, our lips when we speak, our upright posture, and our regular breathing are also made possible by the coordinated contraction and relaxation of muscles. The beating of our heart is muscle work; the movements of our intestines and even our blood pressure and circulation are significantly influenced by muscle activity.

It is motor skills that enable us to turn thoughts into actions, react to our environment, and interact with others. As early as the 1920s, the English neurophysiologist and pioneer of motor skills research Charles Sherrington (1857–1952) summed up the importance of motor skills for our lives in a single sentence. He said: “Movement is all that humanity can accomplish.”

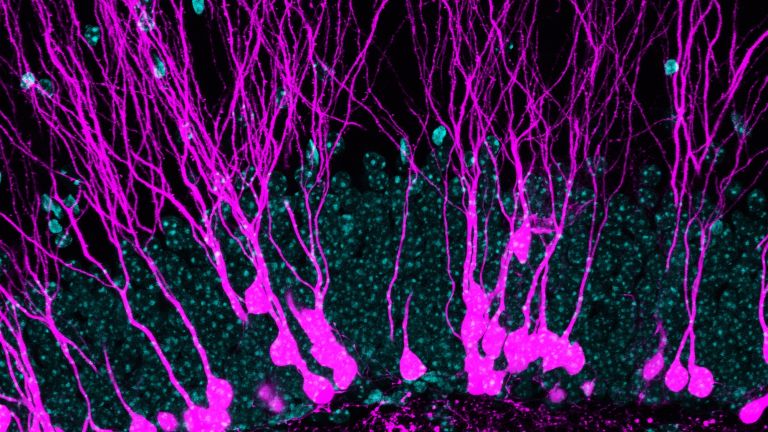

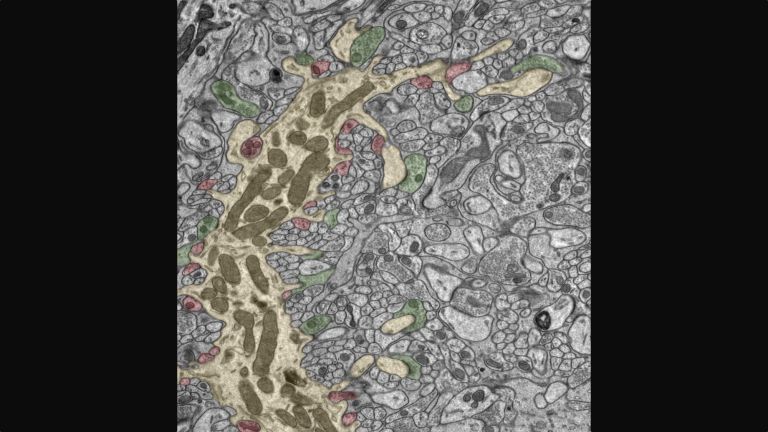

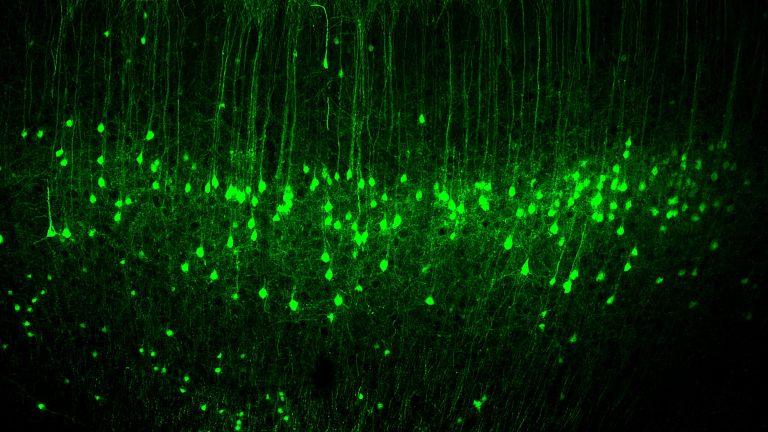

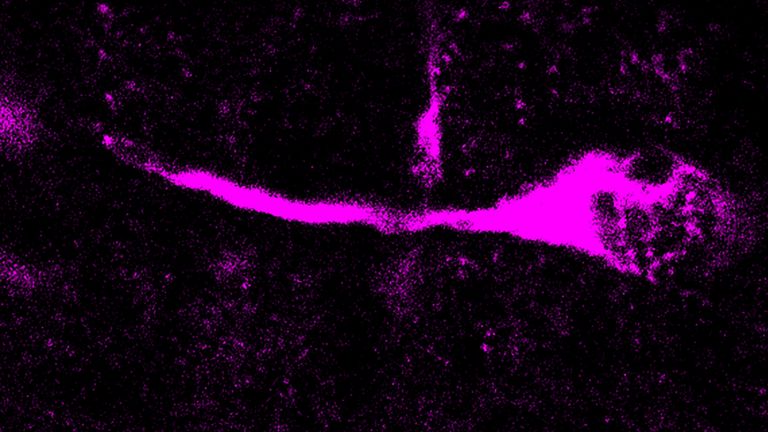

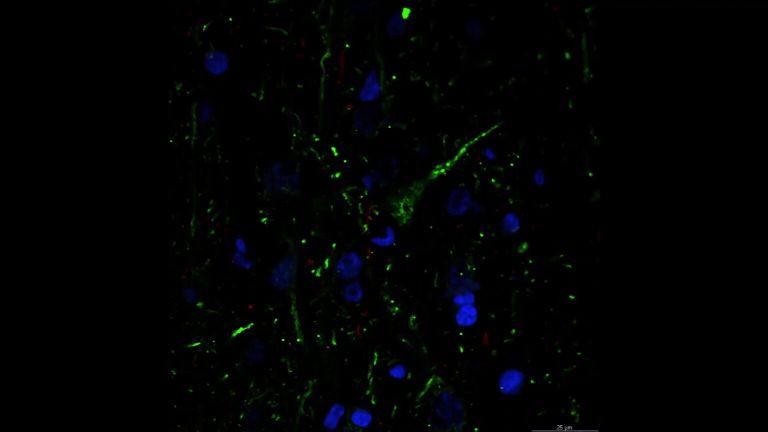

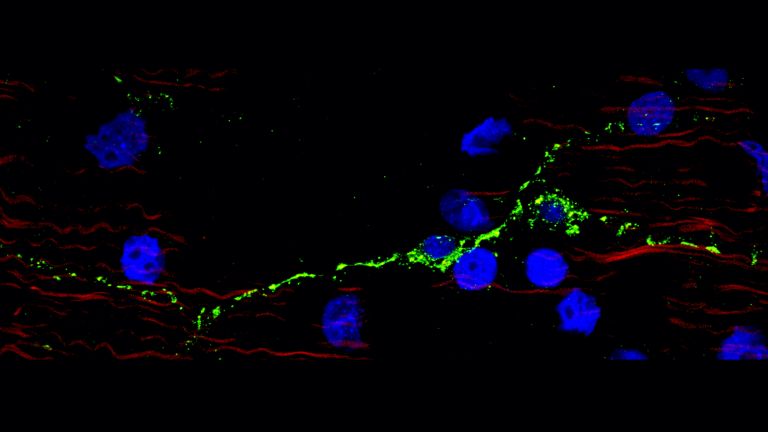

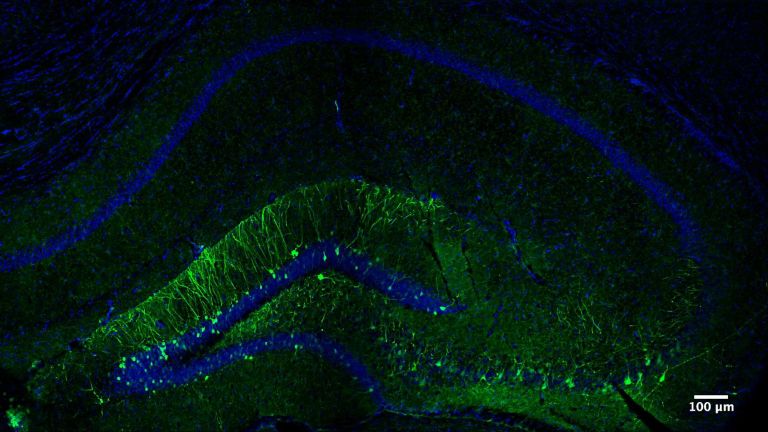

Motor neurons command the muscle cells

Movement is controlled by specific nerve cells called motor neurons, of which there are two types: The lower motor neurons stimulate the muscle fibers of the skeletal muscles via their cell extensions – the axons – and thus cause them to contract. Their cell bodies are located in the spinal cord, the medulla spinalis. This is why they are also called spinal motor neurons. Some reflexes are initiated directly by the lower motor neurons, such as the well-known patellar tendon reflex, in which a light tap on the tendon below the kneecap triggers the lower leg to swing upward. Because the nerve cell impulses responsible do not have to reach the brain, they are particularly fast and can perform protective functions.

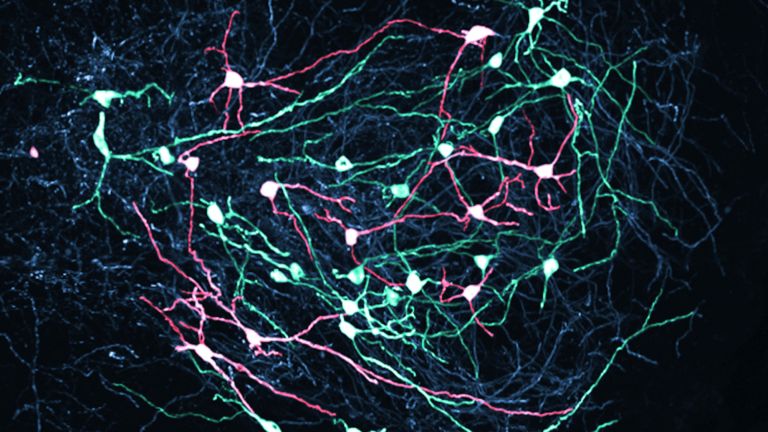

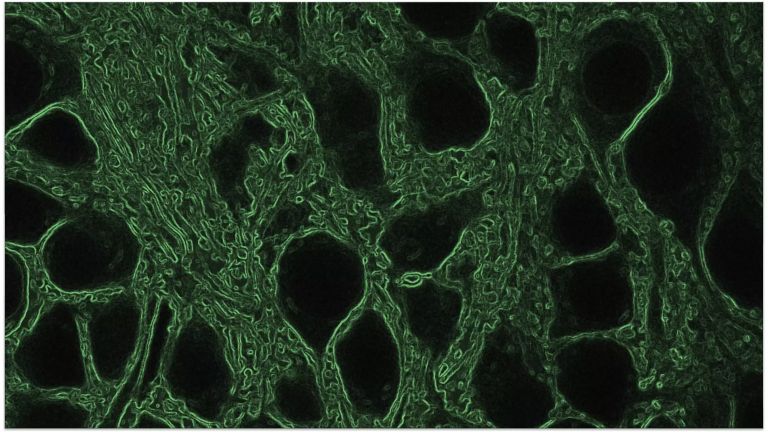

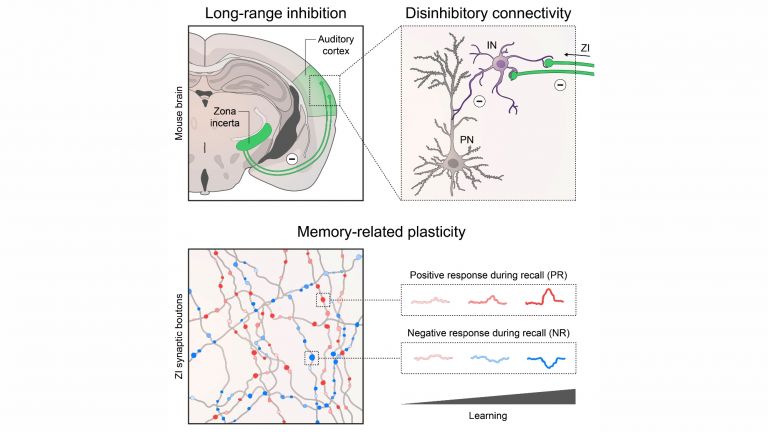

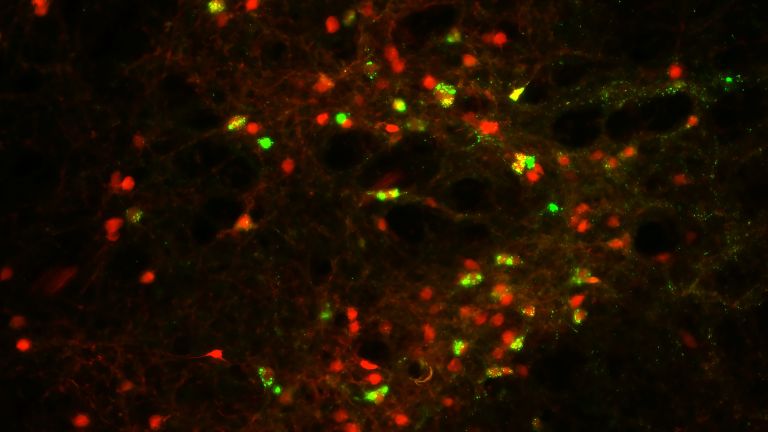

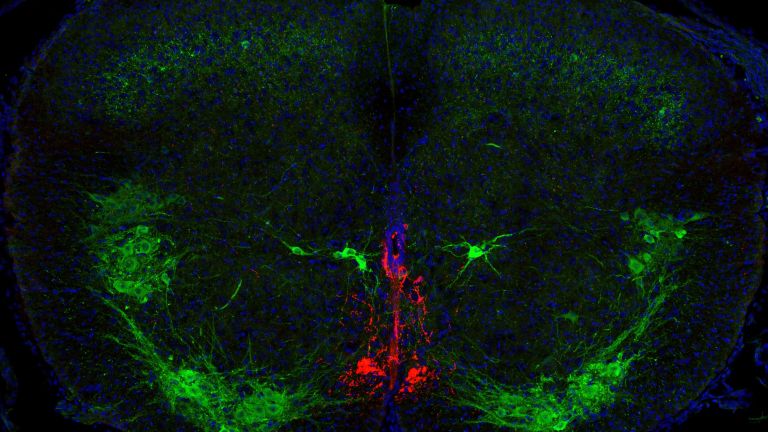

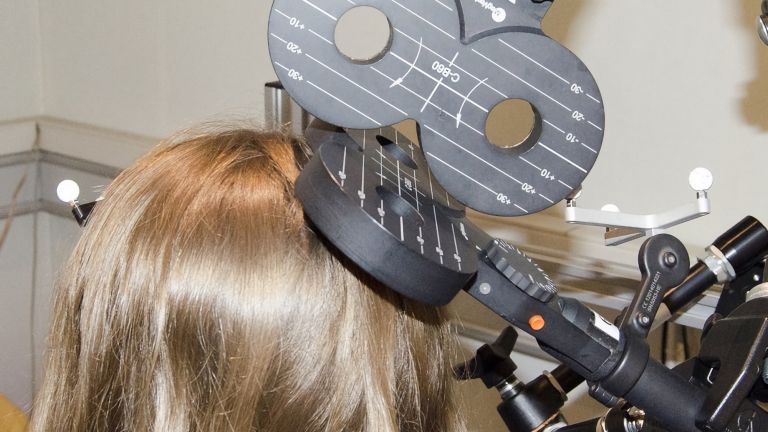

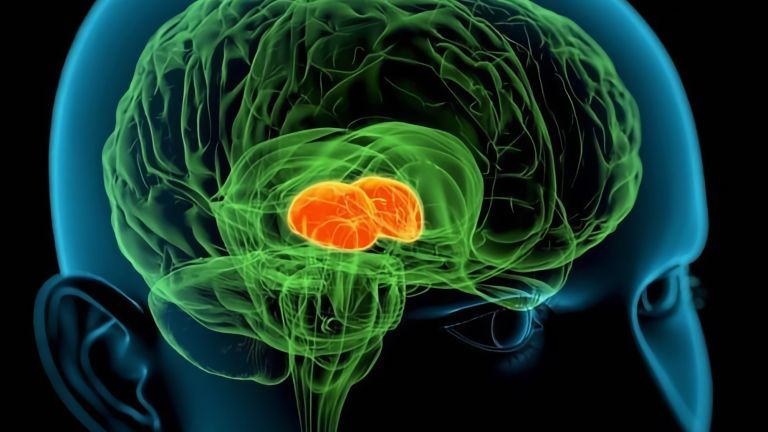

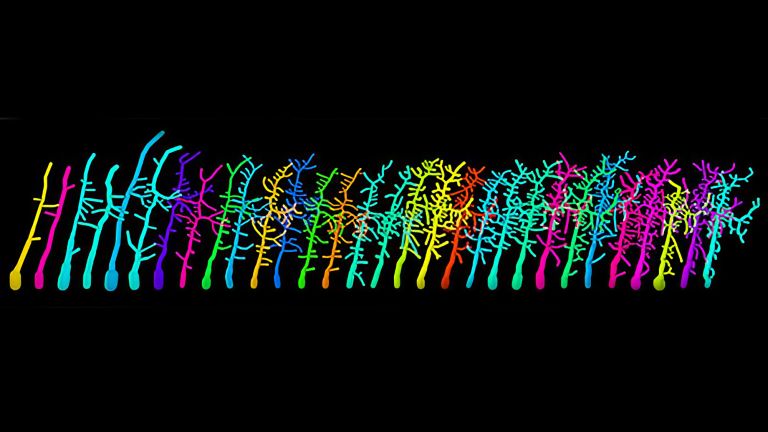

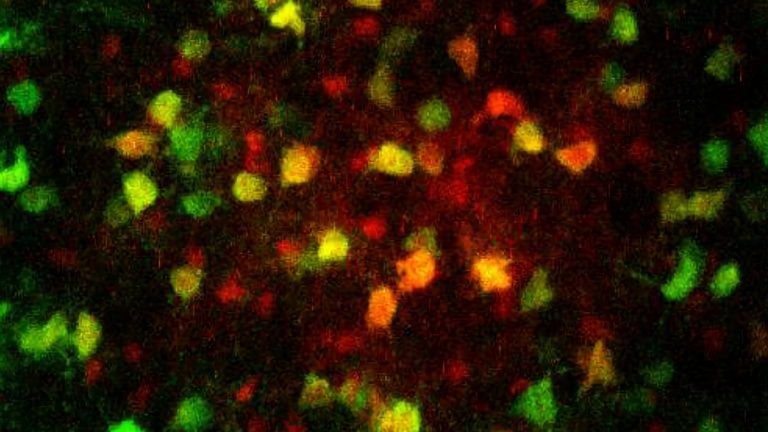

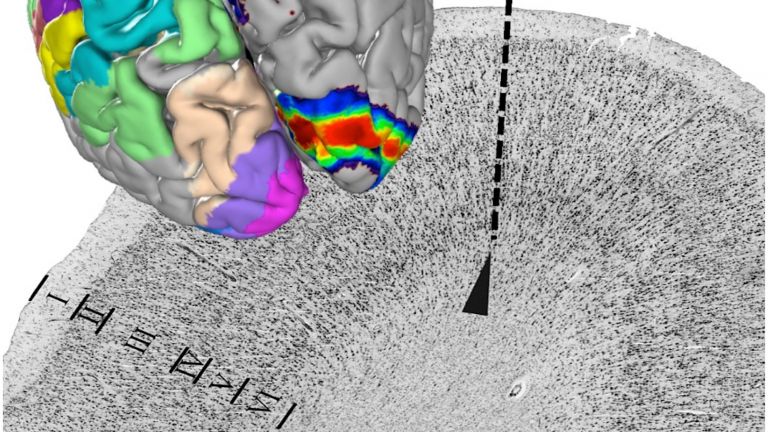

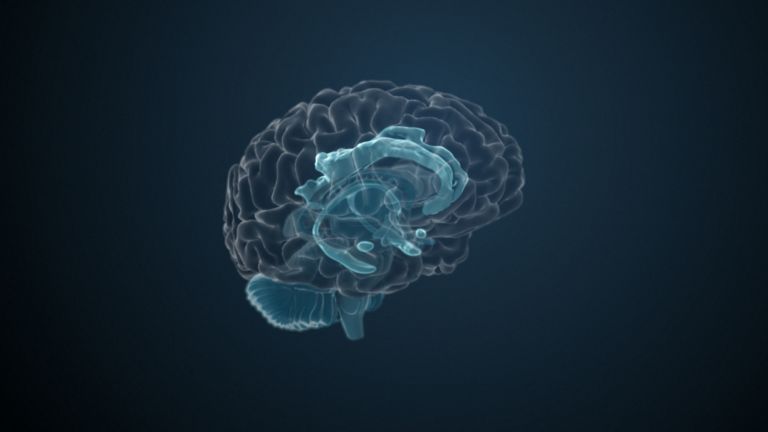

The central motor system is responsible for voluntary movements and also monitors our posture. This includes certain pathways in the brain stem and spinal cord, the cerebellum, and a significant part of the cerebral cortex – the seat of higher brain functions. The motor cortex contains the cell bodies of the second group of motor neurons, the upper motor neurons. Numbering around one million, they send long axons from there to the spinal cord. The upper motor neurons never stimulate a muscle themselves. Instead, they activate the lower motor neurons, which transmit the signal, thereby indirectly triggering muscle contraction. ▸ Highway through the Spinal Cord

Recommended articles

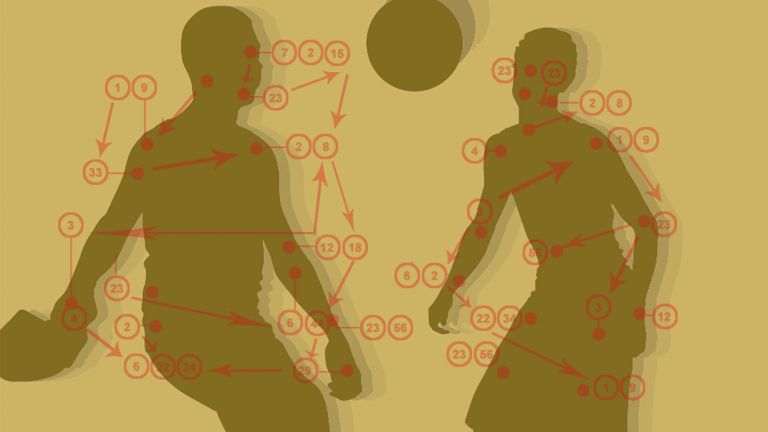

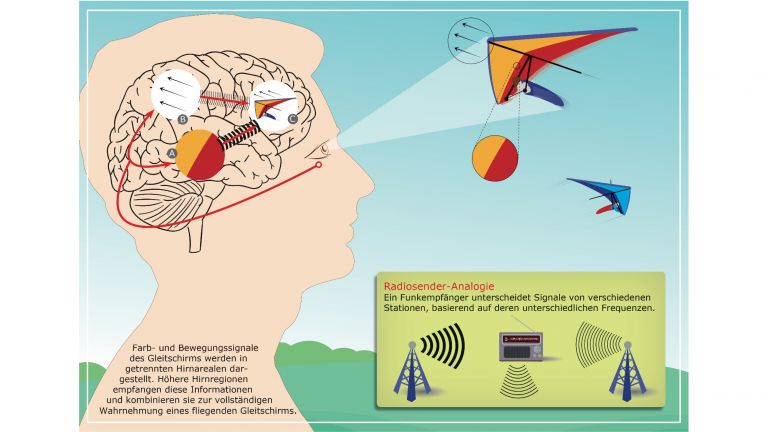

A bidirectional flow of information determines motor function

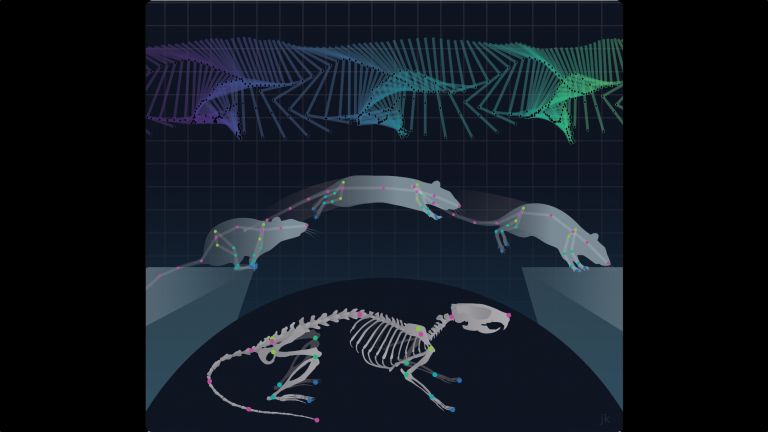

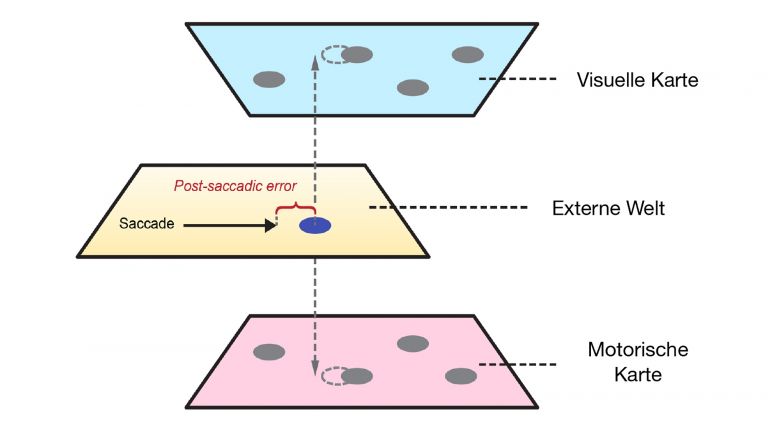

There is a certain division of labor in the motor system: The highest control, so to speak, the authority to move the arm forward or swing the dance leg, is exercised by the motor association fields, which are located primarily in the parietal and prefrontal cortex. This is where the movement goal is determined, for example, that one wants to grab the knife and use it to cut up vegetables, and the most appropriate movement strategy to achieve this movement goal. Once the “what” has been clarified, the motor cortex and cerebellum take over the “how” of the movement sequence. These two areas of the brain are the tacticians in movement control; they determine which muscles should be contracted and in what sequence. The brain stem and spinal cord are then entrusted with the concrete execution of the plan. This is where the (lower) motor neurons are located, from which the muscle cells are ultimately stimulated. ▸ Networks of Movement: Control Strategy, Tactics, Execution

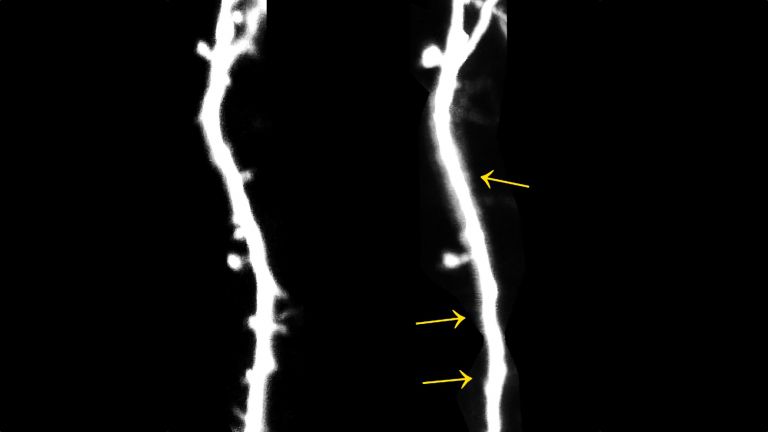

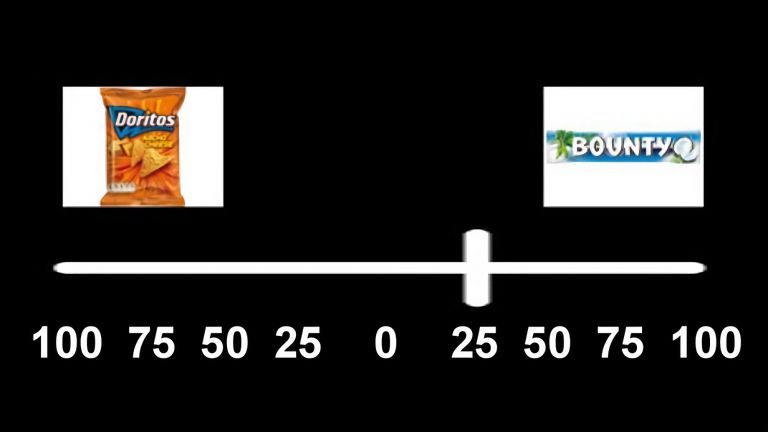

Just how difficult this can be in practice and how many parameters need to be taken into account is perhaps best illustrated by modern robotics. Engineers often work for months to program a humanoid robot with precisely the movements that we perform in a fraction of a second. Determining the necessary force and fine motor skills poses particular problems: How tightly can a robot grip without breaking the glass in its hand, and how precisely must its fingers grasp a pen so that the machine can draw? In the human body, the discharge rate of the motor neurons or the combination of stimulated muscle fibers determine these fine adjustments. They are significantly influenced and guided by sensory feedback that the central nervous system receives before and during the execution of the movement. Thus, a bidirectional flow of information determines every movement. ▸ Motor Fine Tuning: the Modulation of Movements

Once learned, never forgotten

The fact that, unlike robotics engineers, we don't have to think about this any further is partly due to our ability to learn motor skills. Once we have learned most of our daily movements, they become automatic and unconscious, such as walking or the crawl stroke in the swimming pool. Even a quick glance in the rearview mirror or turning on the turn signal is no longer worth a thought for experienced drivers, while novice drivers still have to concentrate on these things.

The advantage of motor learning is obvious: when movements are performed unconsciously, the brain has more capacity to deal with other things. From an evolutionary perspective, this makes sense because it helped our ancestors survive: if running and climbing are automated, you no longer have to concentrate on them when your attention is better focused on other things, such as an angry bear that is trying to kill you.

Fortunately, encounters with bears are rare today. Instead, we now benefit from motor learning in other ways: for example, when a skilled pianist no longer has to pay attention to the notes while playing Ludwig van Beethoven's Moonlight Sonata, but can focus all their attention on their musical interpretation.

First published on August 28, 2011

Last updated on December 1, 2025