The Secret of Taste Perception

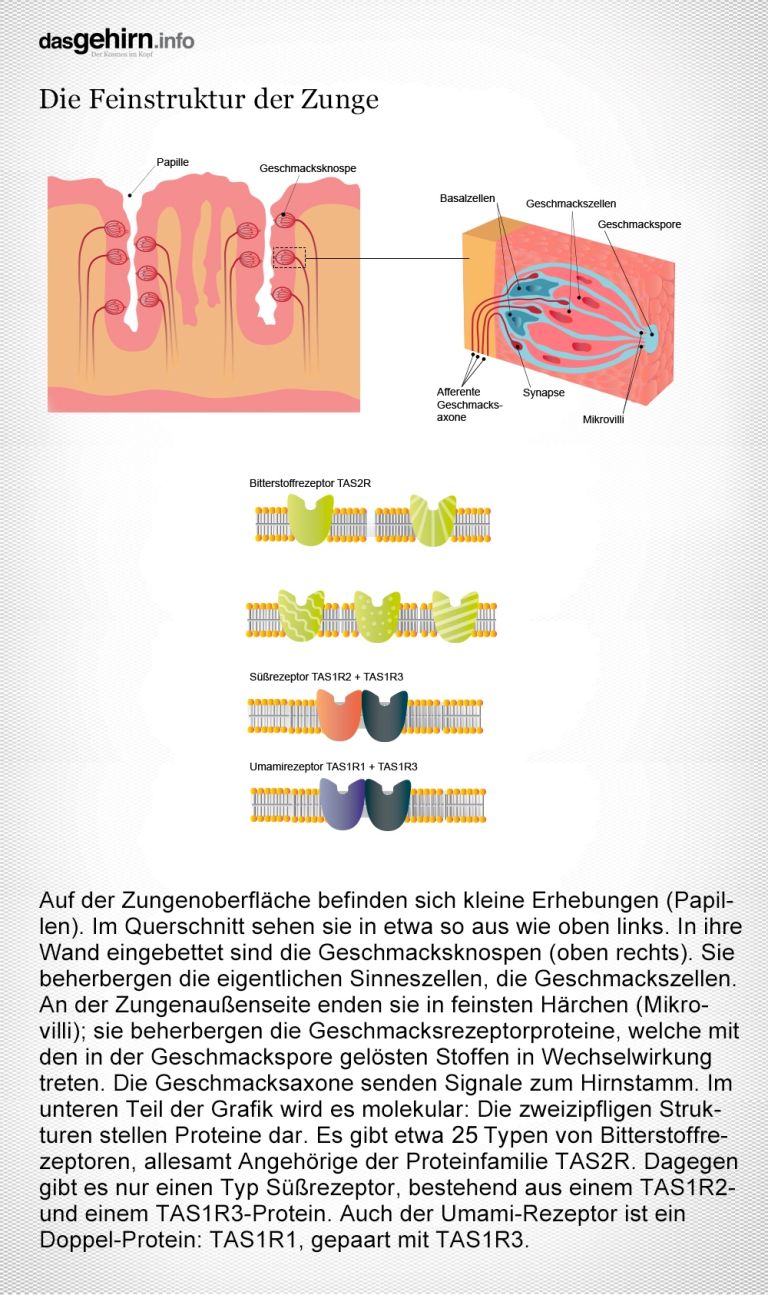

The tongue recognizes at least five taste qualities: sweet, sour, bitter, salty, and umami. The different activities of specific receptors create a taste experience that is also influenced by consistency and smell.

Scientific support: Dr. Maik Behrens

Published: 02.09.2025

Difficulty: intermediate

- Our tongue has receptors for five basic tastes: sweet, sour, salty, bitter, and umami. However, recent studies suggest that there is also at least one receptor for fatty flavors.

- While there is only one receptor for the sensation of “sweet”, approximately 25 different receptors recognize bitter substances in food.

- When it comes to processing taste qualities, two principles are discussed, both of which are likely to be partially true. In labeled line wiring, a specific sensory cell processes exactly one taste quality and transmits it to a specific nerve fiber. The across-fiber theory states that gustatory neurons receive input from a wide variety of taste qualities.

- In addition to taste quality, other sensory information also influences the taste experience. The smell of food in particular contributes to taste perception, but consistency, temperature, and spiciness also play a decisive role.

Contrary to popular belief, the various taste receptors are distributed throughout the tongue – and are not limited to strictly separate areas, as was mistakenly assumed. This is due to a misinterpretation of experimental data: areas with low intensity for a particular taste were interpreted by researchers as areas without any perception of that taste. This led to the creation of the so-called tongue map in the 1940s, which almost everyone has seen at some point, but which is a myth. It shows the tip of the tongue as the sweet region and only at the very back, at the entrance to the throat, is the bitter area located. However, anyone who tests sugar far away from the tip of their tongue will quickly discover that “sweet” can actually be tasted anywhere on the tongue. Nevertheless, the myth persists.

It is amazing what humans can taste. From the creamy, spicy flavor of a Thai curry to the delicate hint of cinnamon in grandma's apple strudel: the human palate can easily identify every known delicacy. This is remarkable because at the lowest sensory level – in the taste buds on the tongue – only a handful of basic tastes can initially be recognized: sweet, sour, salty, bitter, and umami – and, according to recent evidence, possibly also fatty. It is only through clever interconnection in the brain that these are combined to create the overall taste of “apple strudel” or “Thai curry”.

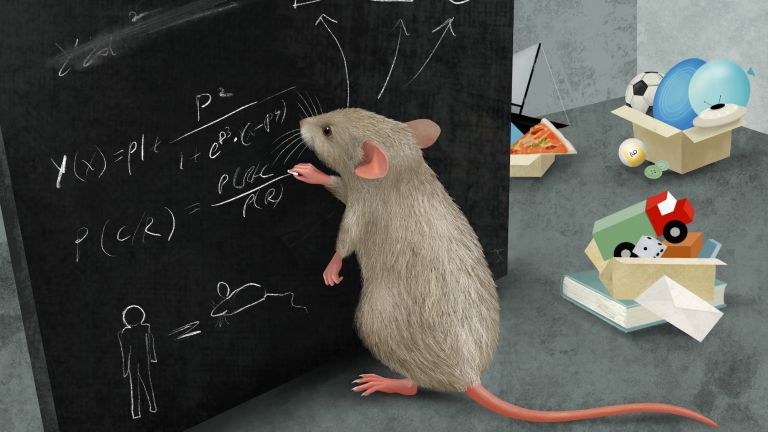

It took a long time to get to the bottom of this complex sensory experience. The first breakthrough came in the 1990s: In the genetic material of rodents, two US researchers, Charles Zuker and Nicholas Ryba, discovered the blueprint for a protein that they rightly suspected was a taste receptor. However, it took several more years before the work of numerous research groups proved that this was one of two subunits of the sweet receptor. Its function was deciphered through special experiments on mice, as Wolfgang Meyerhof, a geneticist at the German Institute of Human Nutrition (Dife) near Potsdam, explains: “Mice in which the genes for both subunits have been switched off can no longer taste anything sweet – including glucose and sucrose. This is because all substances that taste sweet activate this receptor.” Its subunits belong to the same protein family, called TAS1R (formerly T1R).

Receptors for every taste

Other flavors, on the other hand, are perceived by other types of receptors. Their decoding followed shortly after the discovery of TAS1R. However, it turned out that not every flavor is assigned to a single receptor type. For example, there are a number of variants of TAS2R that respond to different bitter substances with varying degrees of intensity. Humans have around 25 such bitter receptors. These can be sorted into three different classes according to their activity: "Generalists recognize more than a quarter of the bitter substances presented. Specialists, on the other hand, are activated by less than three percent of bitter molecules. And then there are moderate bitter receptors, which can recognize between three and ten percent of bitter substances," says Meyerhof. This high degree of specialization is vital, because many toxins taste bitter. The reliable and immediate perception of bitter substances has thus prevented many cases of poisoning since time immemorial.

A completely different function is attributed to another type of receptor: GPR120. Meyerhof and his colleagues are also conducting intensive research on this. The interesting thing about it is that it is activated by long-chain fatty acids. Previously, it was assumed that the fatty taste was mainly conveyed by the consistency of the food. Now, however, there is much to suggest that there is a gustatory component to fat perception. However, this assumption has not yet been definitively confirmed.

Complex interconnection systems

All receptors – whether TAS1R or TAS2R – are located on different populations of taste cells. These populations are therefore specific to bitter or sweet substances, for example. A similar specificity exists in the attached nerve fibers. This is because taste cells are so-called secondary sensory cells – meaning they do not form their own nerve fibers. Instead, they are innervated by afferent sensory nerves, which convert the chemical activity of the sensory cells into electrical nerve signals.

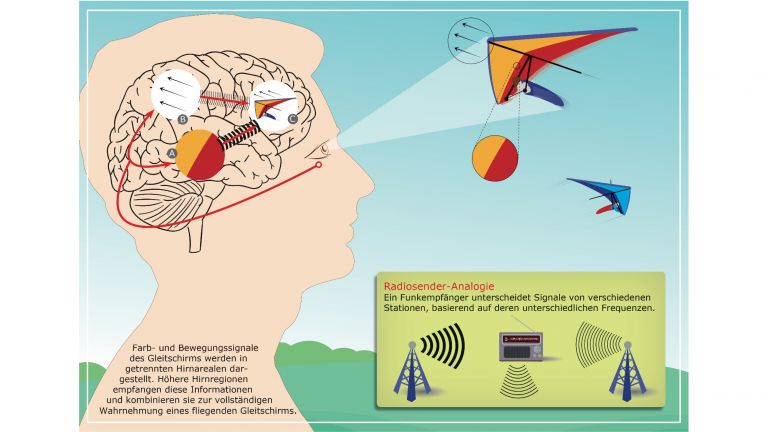

However, there is still much debate about when and how exactly the specific qualities are then interconnected. Two processing principles are under discussion: labeled line and across-fiber. A labeled-line connection means that a specific sensory cell processes exactly one taste quality and in turn transmits it to a specific nerve fiber. The central nerve cells that process or represent taste information also exhibit this specificity. The across-fiber theory, on the other hand, states that the gustatory neurons receive input from a wide variety of taste qualities. “Ultimately, none of the theories has yet been confirmed, as there is experimental evidence for both,” says Meyerhof. According to this, there do appear to be specialized sensory cells – but many gustatory nerve cells are stimulated by stimuli of several taste qualities.

Recommended articles

From tongue to brain stem

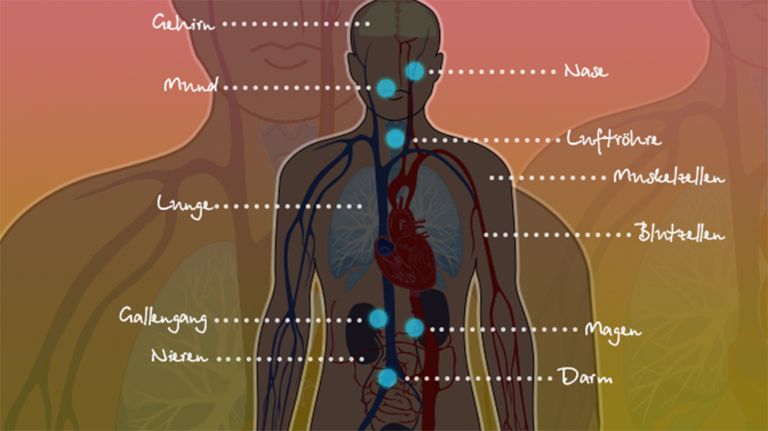

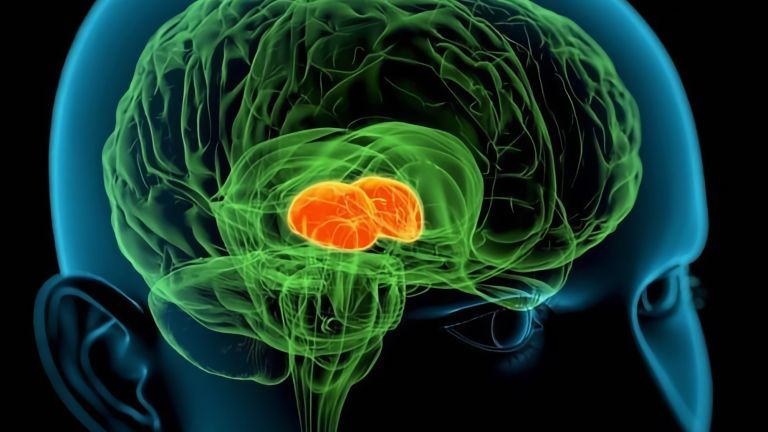

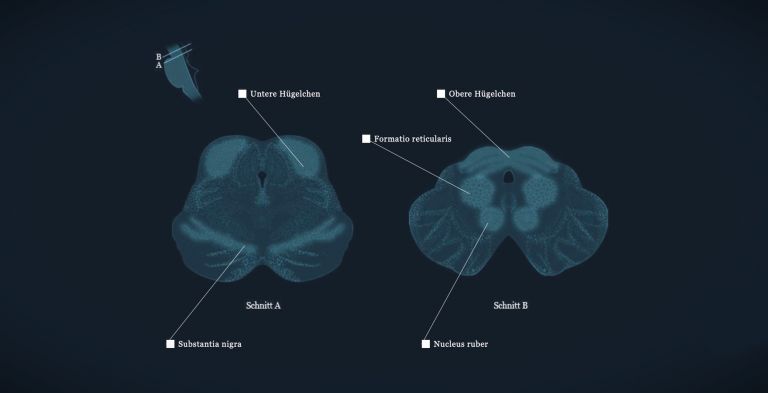

The fibers originate from three of the twelve cranial nerves: the seventh, ninth, and tenth. Their taste fibers travel up to the brain stem, where they end in the nucleus tractus solitarius. Once there, some of the signals are processed directly on site. The brain stem controls basic functions such as salivation, swallowing, and the gag reflex. If something tastes very bitter, for example – and is therefore potentially dangerous – the act of spitting it out can be initiated here.

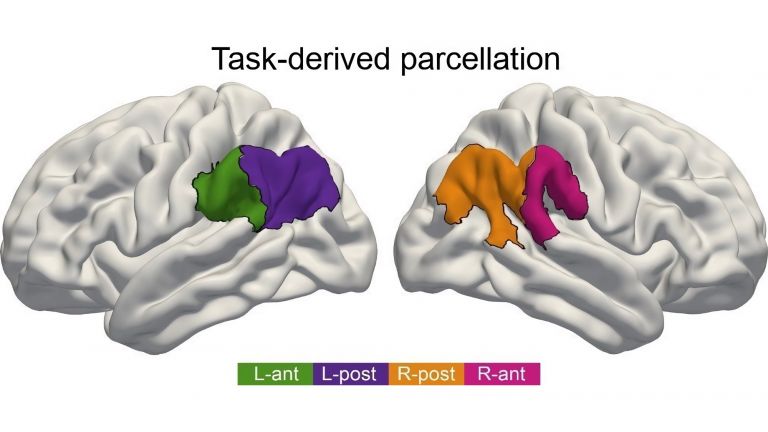

However, most of the taste information is transmitted via the thalamus to the gustatory cortex, the taste center of the brain. It is often said that this area of the brain is divided into areas of different qualities, similar to the visual cortex. However, the spatial representation of taste qualities appears to overlap here, although the exact extent is not known. Meyerhof explains: "While imaging and optogenetic techniques support the existence of spatial maps, most electrophysiological studies show that neurons in the gustatory cortex respond to more than just one taste quality. However, this is hardly compatible with spatially separate processing of the basic tastes."

Extensive overlaps

However, there are likely to be significant overlaps with other sensory qualities as well. This is because the complex taste of food in the broader sense is not conveyed solely by taste receptors, but also by olfactory, pain, and mechanoreceptors. Smell, spiciness, and consistency have a major influence on the taste experience. Researchers assume that up to 80 percent is actually conveyed through smell. So it's hardly surprising that when we have a bad cold, we can hardly “taste” anything – we simply miss the smell of our favorite foods. ▸ Neurogastronomy – a new science of taste

But temperature also plays a major role in taste. Cold and heat influence taste in three ways: they change the consistency, the strength of the aroma, and the sensitivity to certain taste qualities. At 10 degrees Celsius, for example, we taste bitter substances particularly well, while at 35 to 50 degrees Celsius, we taste sweet substances better.

Further reading

- Chemosensory Systems in Mammals, Fishes and Insects, hg. von Wolfgang Meyerhof und Sigrun Korsching, Berlin 2009.

First published on November 27, 2013

Last updated on September 2, 2025