“Fear ensures our Survival”

One in five people suffer from an anxiety disorder at some point in their lives. Anxiety researcher Hans-Christian Pape on barking Rottweilers and frightened rats. The interview was conducted in 2011 and reviewed by Prof. Pape in 2025 to ensure its accuracy.

Published: 25.07.2011

Difficulty: intermediate

Hans-Christian Pape, born in 1956, is considered one of the leading experts in researching the neurophysiological basis of behavior. He was head of the Institute of Physiology I at the Medical Faculty of the University of Münster/Germany and a member of the German Council of Science and Humanities. He researched the neurophysiological basis of behavior, particularly fear and anxiety, as well as the regulation of sleep and wakefulness. Pape has received several scientific awards, including the Leibniz Prize from the German Research Foundation (1999) and the Max Planck Research Prize (2007). Pape does not describe himself as an anxious person but sees his own fear as a protective mechanism against dangerous situations.

Recommended articles

Mr. Pape, you are a fear researcher. When was the last time you were really afraid?

I remember it clearly. At the beginning of the year, my wife received a diagnosis from her doctor that was not without its problems. I found that frightening.

Does it help in such situations that you have been researching the phenomenon of fear for years?

At the very least, you can explain your own reactions better and thus control them a little better. Above all, I would certainly recognize if I were to develop a pathological form of fear.

Does that mean there is good fear and bad fear?

First, we need to distinguish between three terms: shock, fear, and anxiety. Shock is a reflexive reaction to a specific event, such as a loud noise or a barking dog. It involves fairly simple circuits in the brain. Fear, on the other hand, often involves stored information. By retrieving this information, we can better interpret a situation: if it is only a small Chihuahua, there is hardly any danger, but if it is a Rottweiler approaching us with signs of aggression, then we know that we must fear for our health.

So fear is definitely useful ...

Yes, a large, barking, aggressive animal could be threatening. Fear is therefore important. It prepares us to ward off or escape this potential danger. This is a very basic behavioral strategy that is present in almost all vertebrates and ensures their survival.

And anxiety?

Anxiety is an exaggerated fear response. It can occur without a direct trigger, and the reaction is often incomprehensible to an outsider.

So where does this anxiety come from?

It can be memories, for example. If a child was attacked by a dog at the age of three or four, this traumatic experience can lead to a trace of fear being created in the child's brain that other experiences can only partially cover up. This memory can then be recalled in situations where the trigger, such as the dog, is not actually present. A noise that resembles barking, an encounter with another animal, or even just the idea of one could trigger panic-like fear in this person.

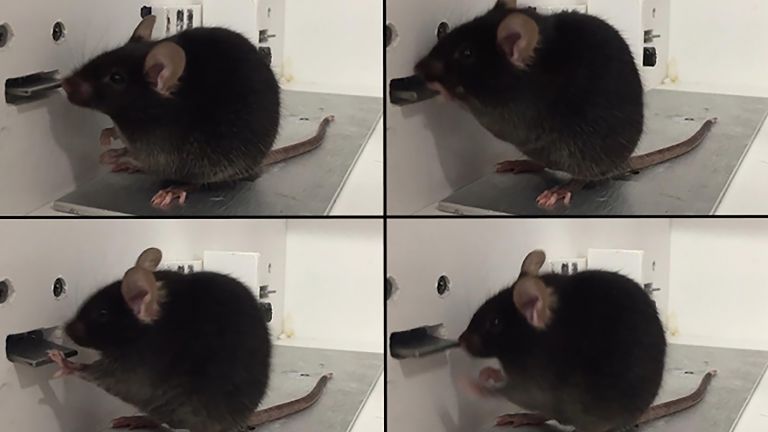

The most popular fear models for researchers are rats, which are played a sound and then given a weak electric shock. After a while, the animals show a fear response when they hear the sound alone. What happened?

It is only a weak electrical stimulus on the foot, similar to touching a pasture fence. A simple, associative memory trace has formed in the rodents' brains, linking the sound with this frightening stimulus – like the example of the barking, aggressive dog. The sound is associated with the experience of the electric shock.

Fear researcher Joseph LeDoux has studied such animals and shown that a region of the brain called the amygdala plays a crucial role in the development of fears. Is this our fear center?

The amygdala is very important, but it is not solely responsible for our fear and anxiety. We know that fear can be developed towards certain objects, such as spiders, dogs, or even a particular sound. But you can also be afraid of certain contexts, such as heights or social encounters. Other brain structures, such as the hippocampus, are very important in this regard. Take the rat from the example above out of the cage where it had the frightening experience and place it in a different environment. If you put the rat back in the first cage a day later, it will show fearful behavior even if no sound is played. The rat has learned to associate not only the sound but also the environment with fear – it is afraid of the entire context, to which the hippocampus and its connections to the amygdala contribute significantly.

So, if I am mugged in the park at dusk and I encounter the mugger again ...

... then the fear you feel is primarily the work of the amygdala. But the fear you feel when you are walking alone in the park in the evening is attributable to the influence of the hippocampus.

And what if I walk through this park again and again in the evening and nothing happens to me?

It's like when you repeatedly place a spider on the arm of someone with a spider phobia and they realize: It's not doing anything to me. The patient learns that a spider does not necessarily pose a threat. In the same way, the victim of an attack can learn that a park at dusk does not necessarily pose a threat. Another brain region, which is much younger in evolutionary terms, is important for this new assessment: the prefrontal cortex.

So, fear is represented in the brain by a kind of triumvirate?

Exactly. The amygdala is responsible for simple forms of associative fear learning, while the hippocampus plays an important role in more complex forms and the context of fear, and the prefrontal cortex is the higher authority. This is the authority that controls fear and anxiety memory and can also override the initial experience of fear. To do this, the prefrontal cortex creates its own memory trace, known as extinction memory, which can overwrite the fear memory.

Is the initial experience of fear erased?

No. The queasy feeling remains when you walk through the park. This is because the memory is not usually erased. A kind of balance is established between the amygdala and hippocampus on the one hand and the cortex on the other. This balance determines the fear response. This is extremely important. If a patient is treated for an anxiety disorder, for example after a traumatic experience, and the therapy is successful, they often live for months without any symptoms. But then suddenly, in a so-called flashback, the fear can return. One explanation for this is that the balance between the extinction memory and the initially created fear memory has been shifted back.

Such patients are not exactly rare. Almost half of all people who go to a psychiatrist cite disturbed anxiety behavior as the reason: phobias, traumas, anxiety disorders.

That's right. In our culture, statistically speaking, one in five people will suffer from an anxiety disorder requiring treatment during their lifetime. However, those affected only recognize an anxiety disorder when the anxiety impairs their quality of life. This can go so far that patients avoid all social contact and all contact with their environment. In addition to neurobiological processes and environmental influences, genes also play a role. A whole series of genes have been identified that form the basic framework of an anxiety predisposition, so to speak, on which individual experiences are built.

Back in 2007, researchers succeeded in selectively erasing one of these fear memories in a mouse that had learned to react fearfully to two different sounds. How far are we from being able to selectively erase fears in patients?

It already works very well in animal models. We know that certain processes have to be repeated over and over again in memory in order to anchor a memory in the long term. To do this, complex signaling pathways in the nerve cells of the amygdala, hippocampus, and prefrontal cortex must be repeatedly traversed. If you intervene there, for example pharmacologically or simply by re-presenting the fear-inducing stimulus, you can actually erase the memory trace. Recent evidence shows that this is also possible in humans, provided it happens within hours of the fear experience. However, these are still scientific experimental studies. The road to therapeutic application is still very long. We should not suggest that we will be able to treat patients in this way in five years, for example.

Some people find the idea that we will be able to selectively erase memories in the future very threatening.

I can understand that. But I also think that we should keep the positive aspects of this goal in mind: there are a large number of patients whose quality of life is severely limited by excessive anxiety, panic attacks, or severe post-traumatic stress disorder. And the number of these patients is rising. This is a major health policy and economic problem.

Of course, the results of biomedical research offer potential for abuse – in our field, there is a tendency to speculate about brainwashing, especially in the military. But we really have the opportunity here to treat the most common psychiatric disorders with targeted new therapies. Just consider that 90 percent of soldiers returning home from Afghanistan develop anxiety disorders and require virtually permanent treatment.