Movement Planning: Reaching your Goal with Tactics

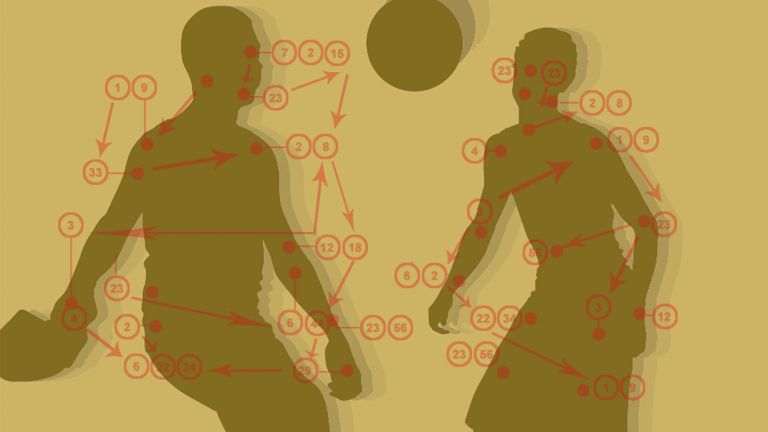

Will the handball player throw the ball from a run as a tricky bounce shot into the middle of the goal, or will he hammer it from a jump into the upper right corner? No matter how and where, several areas of the brain are involved in planning complex movements.

Scientific support: Prof. Dr. Hansjörg Scherberger

Published: 01.12.2025

Difficulty: serious

- Several regions of the brain are involved in planning movements, each with different areas of responsibility

- The prefrontal cortex assesses the overall situation and decides which action is the right one.

- The posterior parietal cortex perceives the position of the body in space and directs the movement toward a goal.

- The basal ganglia act as a filter, selecting desirable from undesirable actions and suppressing automatic reactions to environmental stimuli.

- The supplementary motor cortex and the premotor cortex draft a movement plan and coordinate the various individual movements with each other.

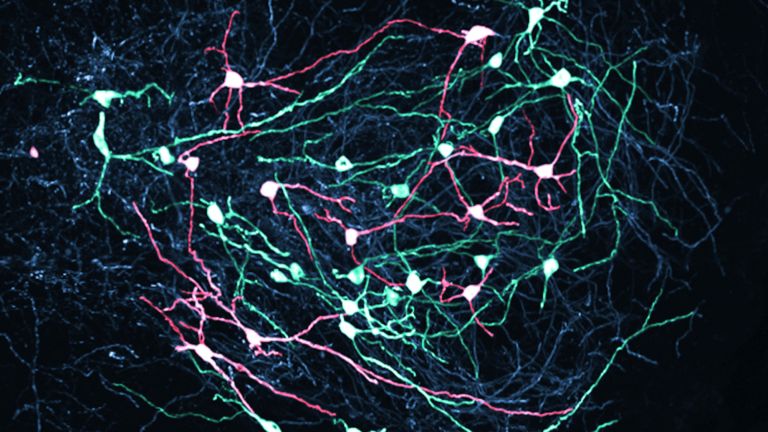

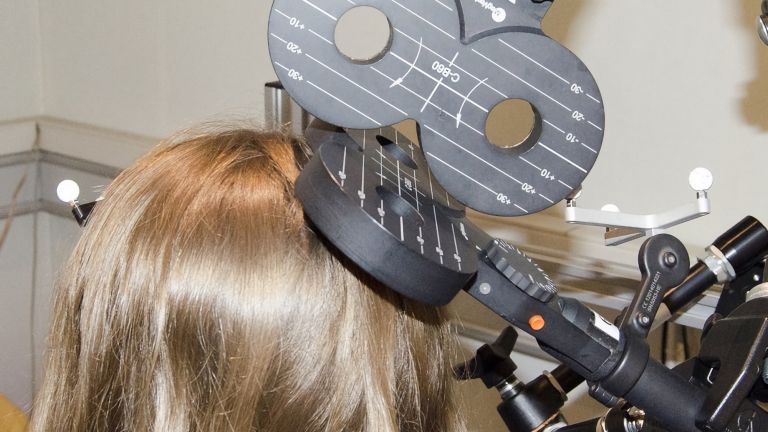

What is different when we only imagine a movement compared to when we actually perform the movement? Knowing this allows conclusions to be drawn about the mechanisms of movement control and has therefore been investigated by neuroscientists using functional magnetic resonance imaging. Surprisingly, largely the same neural networks are active in both scenarios: in the premotor cortex, the prefrontal cortex, the basal ganglia, and the posterior parietal cortex. There are differences in the supplementary motor cortex – there, other subregions fire when the situation only exists in the imagination. In addition, parts of the prefrontal cortex are active – researchers suspect that these areas are responsible for suppressing a movement and thus preventing a movement plan from being implemented before it is released.

The handball player runs toward the goal with the ball. The goalkeeper stands a few meters away directly in front of him, two opponents approach him from the right, while a player from his own team waits for the pass on the left front. What will our protagonist do? A tenth of a second later, the spectators know the answer: the ball hits the top right corner of the goal with full force – the goalkeeper had no chance of saving it. As easy as it looks, the attacking player's brain had to work hard to accomplish this task – complex voluntary movements such as throwing a ball like this need to be well planned.

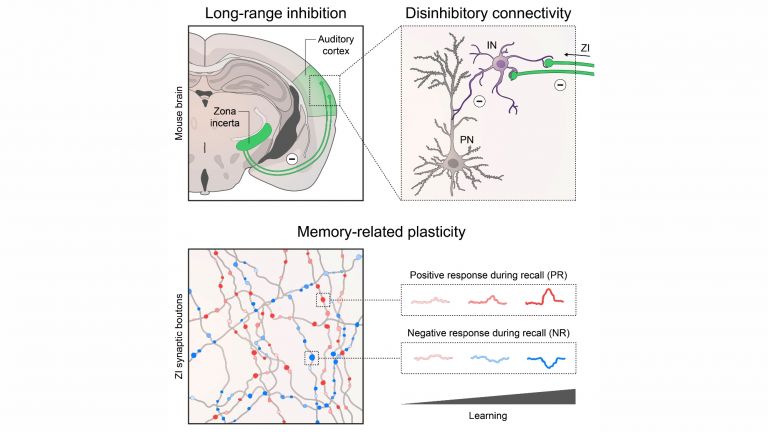

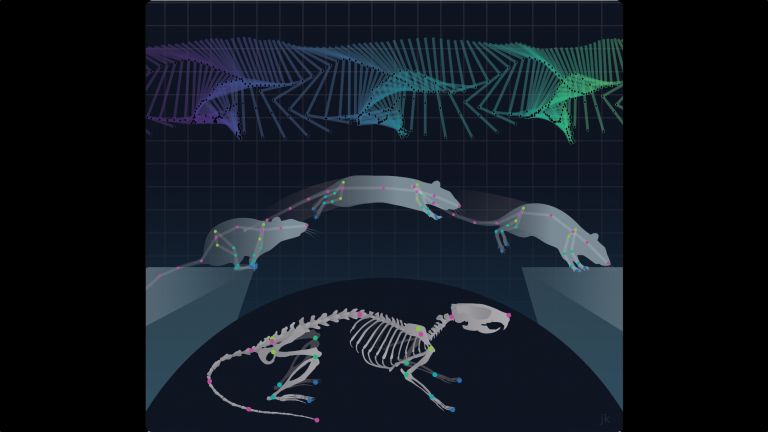

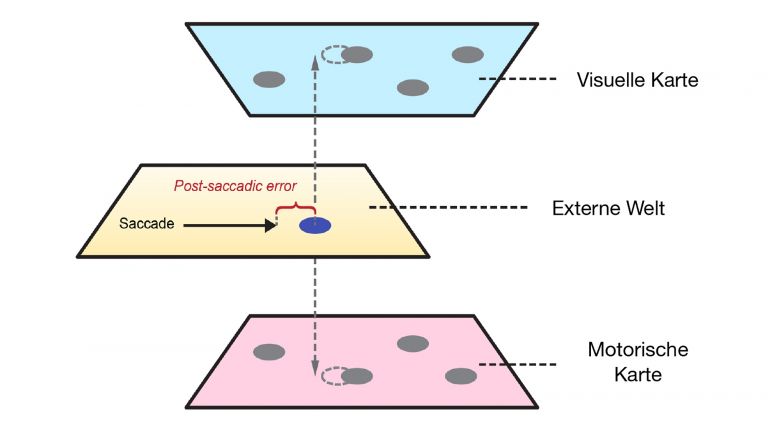

In targeted motor actions, many areas of the brain work together in a functional loop. They process a number of visual and other sensory stimuli – such as shouts from teammates or the unpleasant feeling of sore muscles in the arm from yesterday's game – combine the individual pieces of information into a larger whole, retrieve memories of similar situations, filter out unwanted actions, make a decision about the movement goal, determine the most suitable strategy for achieving it, filter out non-goal-oriented action options, and, taking all these parameters into account, develop a movement plan, which is then put into action by the muscles in the final step: WUMM – into the top right corner. Or rather: WUMM or a tricky bounce or a pass to a teammate. Research findings from the German Primate Center in Göttingen show that the brain plans several alternative movement patterns in parallel before finally deciding on one of the options.

Step 1: Making a decision

When making decisions about courses of action, and thus also about movement sequences, such as throwing a ball in a running competition, the association fields of the neocortex play an important role. These are the parts of the cerebral cortex that do not receive input directly from the sensory organs, but instead receive information from other cortical areas and also pass on commands to them. The posterior parietal cortex and the prefrontal cortex play a decisive role in the planning of movements. They are the highest decision-making levels in cortical movement planning.

The prefrontal cortex, or PFC, acts as a collection and integration point for pretty much all information that is relevant for assessing a situation. It receives signals from the handball player's external environment as well as from their internal environment, meaning that it is always up to date on their feelings and motivation. The PFC evaluates the information, selects the right behavior or course of action from the multitude of possibilities, and suppresses the rest.

Presumably, the prefrontal cortex is also the part of the brain that decides that the handball player will throw into the upper right corner – but we don't know this for sure, because other areas or an entire network could also be involved. It also helps to transfer the event into memory so that it can be used in the future, i.e., for the next attack or the next game.

Where am I and where do I want to go?

However, in order for a goal-oriented movement to be planned at all, and for the necessary spatial-temporal sequence of muscle contractions to be organized, another prerequisite is necessary: the awareness of where the body is, where it wants to go, and how it gets there. This is where the posterior parietal cortex comes into play. Its main task is to process information about the body's current position, direct movement toward a specific goal, and coordinate hand movements and visual stimuli, for example. For our handball player, this means that the posterior parietal cortex allows the player to accurately assess how far he is from the goal and in which direction he needs to throw. It also triggers the body to execute the throw.

If the parietal cortex is damaged, playing handball becomes virtually impossible. In this case, a player would no longer be able to perceive the many different stimuli that come at him – his teammates, the goalkeeper, the goal, the ball, shouts, muscle soreness– simultaneously grasp their meaning, and translate them into movement. If he still managed to throw, he would miss the goal. Patients with damage to the parietal cortex cannot even pour water from a bottle into a glass – even after many attempts, they fail. They are unable to perceive the bottle and the glass at the same time. Opening doors, hitting a nail with a hammer, or using a screwdriver also becomes impossible.

Support from other areas of the brain

Of course, memory also plays an important role in planning movements. How a similar situation turned out in the past and what the handball player knows about his own strengths and the weaknesses of the other players influence the overall decision of whether and how a movement is executed.

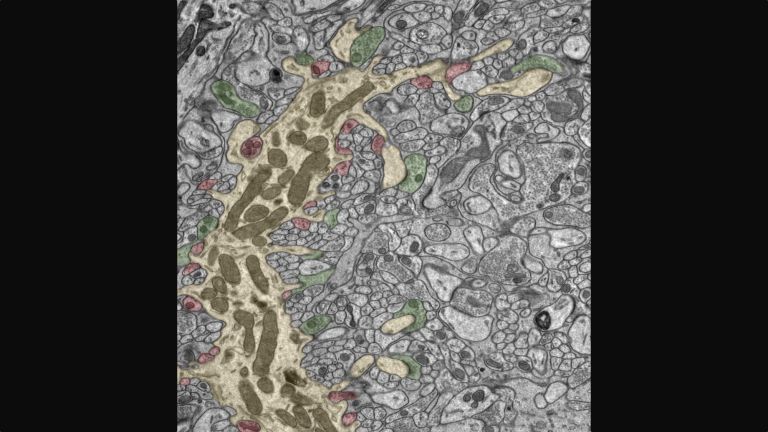

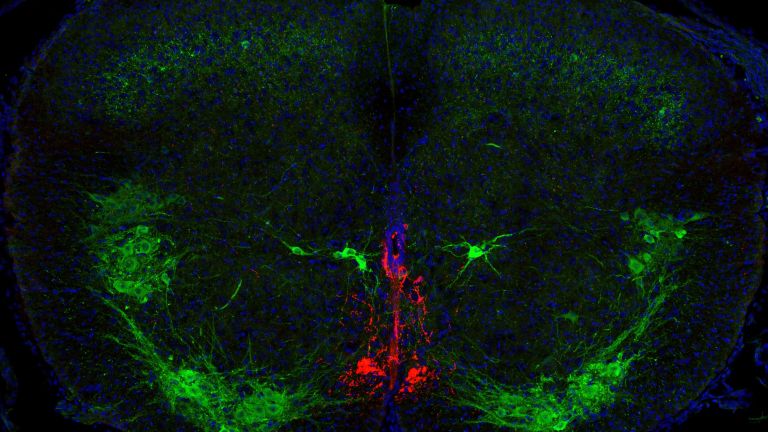

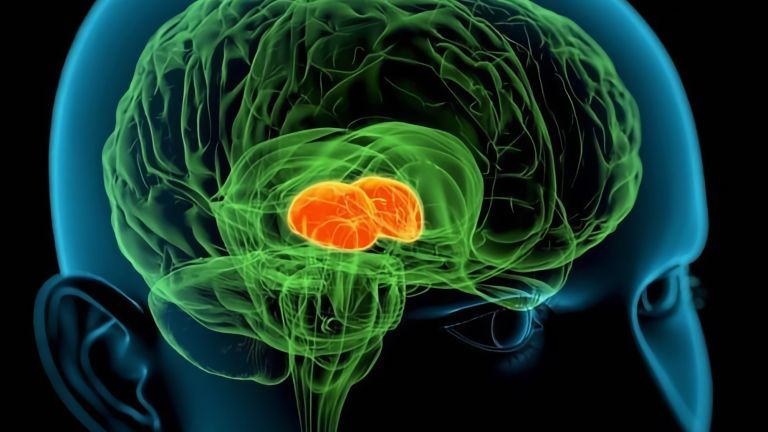

The association fields of the cortex also work closely with the basal ganglia. These consist of several subcortical nuclei, i.e, nuclei located below the cerebral cortex. Although the function of the basal ganglia is still far from being fully understood, brain research assumes that they play a key role in the selection and further processing of currently required patterns of action, and thus also in the planning and initiation of motor actions. Apparently, they help to translate sensory stimuli and memory content into the correct movement responses.

Basically, the basal ganglia act as filters: they select inappropriate actions right from the start. For example, there may be a spectator sitting on the sidelines eating a hot dog. Even if the handball player is feeling terribly hungry and the smell of the food is making his mouth water, he will not interrupt the game to take the hot dog away from the spectator and eat it himself. This is certainly an extreme example, but it illustrates well how the basal ganglia suppress automatic responses to environmental stimuli.

Conversely, they are needed to actually initiate intended movements, i.e., to put the movement plan into action. This can be seen in patients with Parkinson's disease, a condition associated with the death of nerve cells in certain areas of the basal ganglia. Those affected suffer from a lack of movement and have great difficulty, for example, taking the first step when they want to go to the toilet.

The basal ganglia form subcortical processing loops that process cortical signals and project them back via the thalamus to the cortical area from which they received input. In this way, they influence almost all areas of the brain with the exception of the primary visual and auditory centers, in particular the primary motor, supplementary motor, and premotor areas. The latter two cortex regions are involved in both decision-making and movement planning, which determines how the action is to be performed.

Recommended articles

From rough sketch to detailed plan

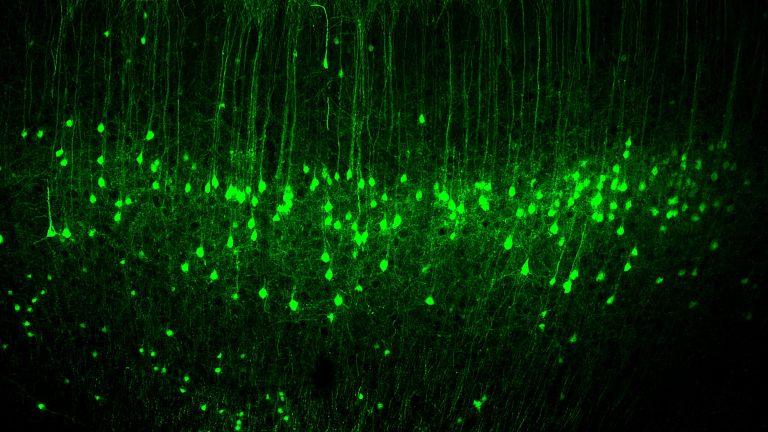

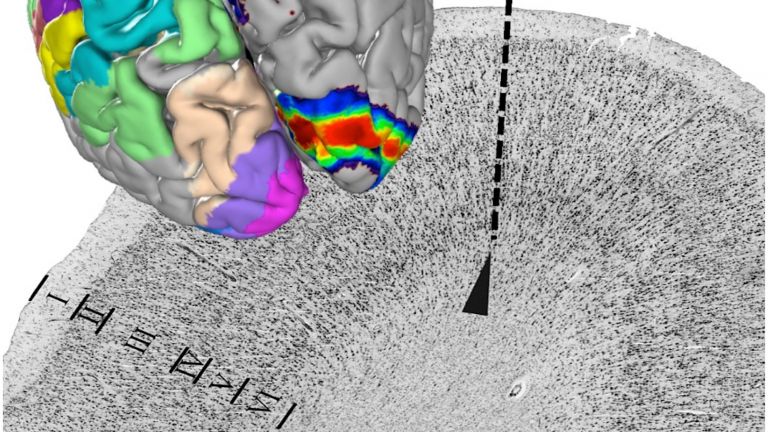

The medially located supplementary motor area (SMA) and the lateral premotor area (PMA) are sometimes referred to collectively as the secondary motor cortex. They create movement plans that specify the exact spatial and temporal sequence of events, i.e., when which movement is to be performed with what force. The SMA and PMA then store these plans until the right moment to implement them arrives. The more often such a motor program is executed, the more optimally the various muscle groups work together. The movement plan is thus refined with each retrieval. This is one of the reasons why practice makes perfect – even when throwing a handball.

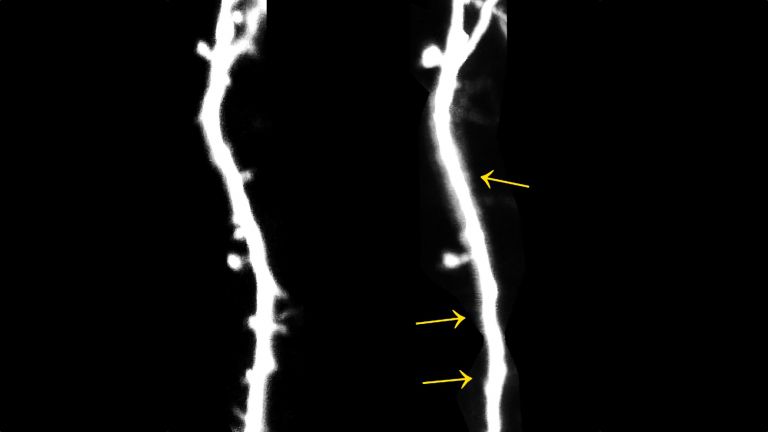

Science cannot yet fully explain how parameters such as direction, duration, and strength are encoded in SMA and PMA in detail. However, experiments show that the nerve cells there are already active before the start of a motor action. They therefore play an important role in movement planning.

The two cortex areas apparently perform slightly different tasks, although many questions remain unanswered here as well. Recent research suggests that the supplementary motor area is responsible for creating plans for self-generated voluntary movements, such as throwing a ball. The premotor area, on the other hand, becomes more active when it comes to responding to external stimuli with movements – for example, catching a ball in the air.

Different areas of the cortex for different tasks

The supplementary motor cortex is hardly active during simple finger flexion and extension, but it is fully engaged when throwing a ball at a goal, because this requires the coordination of many different muscles in the arms, legs, and torso. It is also needed to learn sequences of actions, in the case of the handball player, for example, to suddenly stop, then raise the arm, and throw the ball forcefully in one direction. The supplementary motor area is also needed to prepare and initiate complex movement sequences. Patients with damage to both sides of the SMA have problems planning and executing complex movement sequences.

The tasks of the premotor area include controlling visually guided movements, such as when a ball is thrown at someone. Closely connected to the visual centers of the cerebral cortex via numerous nerve pathways, it transforms and integrates information coming from there into motor programs. In other words, the PMA creates a movement plan that is matched to the external stimulus. For example, how fast and how far to stretch the arms and close the hands in order to catch a ball flying in from the left.

However, what generally applies to the neurobiology of movement planning also applies here: much of it is theory for which there is scientific evidence, but definitive proof is still lacking and further research is needed. One thing is certain, however: both areas of the secondary motor cortex play a decisive role when it comes to designing complex voluntary movements and preparing for their execution.

The supplementary motor and premotor areas are closely connected to the primary motor cortex, the area of the cerebral cortex where movement plans are put into action. The primary motor cortex sends the final command to the spinal cord to contract the corresponding muscles and – in the example of the handball player – to execute the throw. Whether the movement goal, i.e., scoring a goal, was achieved with this movement plan is stored in the memory and can then be retrieved the next time, so that the goal scorer can score a second time.

Further reading

- Klaes, C. et al: Choosing Goals, not Rules: Deciding among Rule-based Action Plans. Neuron. 2011; 70 (3):536 — 548 (to the abstract).

First published on August 28, 2011

Last updated on December 1, 2025