The Fear Circuit

The sight of a spider or a shadow darting across the dark triggers the brain's sensitive alarm system in a flash, resulting in sweating and sheer terror. Often, it is a false alarm. But the brain quickly corrects itself.

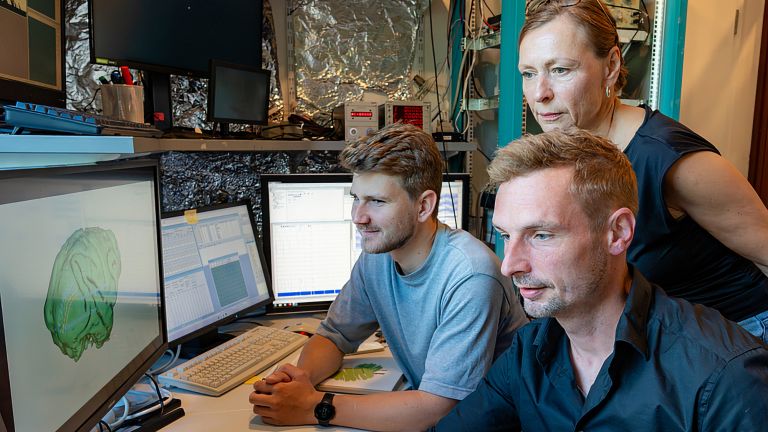

Scientific support: Prof. Dr. Alfons Hamm

Published: 11.09.2025

Difficulty: intermediate

- The amygdala assesses dangers and controls the cascade of fear responses.

- It receives a rough outline of the situation directly from the thalamus in order to quickly assess the danger.

- A more detailed analysis is provided a little later by the slower route from the thalamus via the neocortex and the hippocampus.

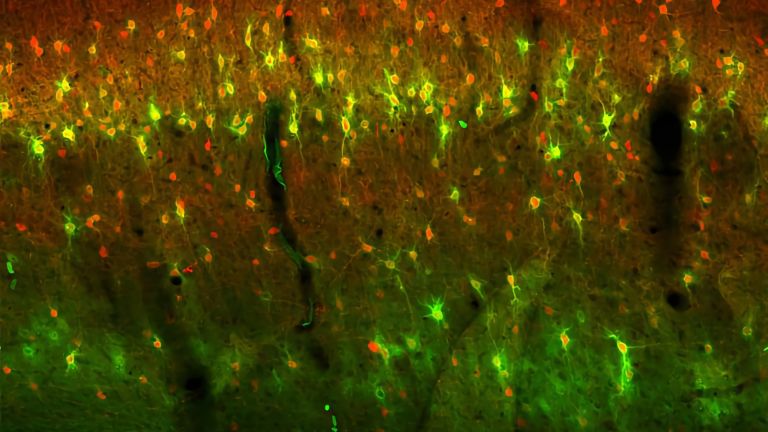

“Is emotion a magical product,” asked neuroanatomist James Papez (1883–1958) in 1937, “or is it a physiological process which depends on an anatomical mechanism?” Papez opted for the second answer. He believed that emotion was a product of the limbic system, which physician Paul Broca (1824–1880) had already described in 1878 as the “grand lobe limbique”. This phylogenetically ancient area consists of several connected structures, including the amygdala, the hippocampus, and the septum. However, anatomists still argue today about which structures exactly belong to the limbic system and whether it can even be called a “system”. This is because some of the components of the limbic lobe play a role in emotions and sexual behavior, while others are responsible for memory, motivation, and navigation.

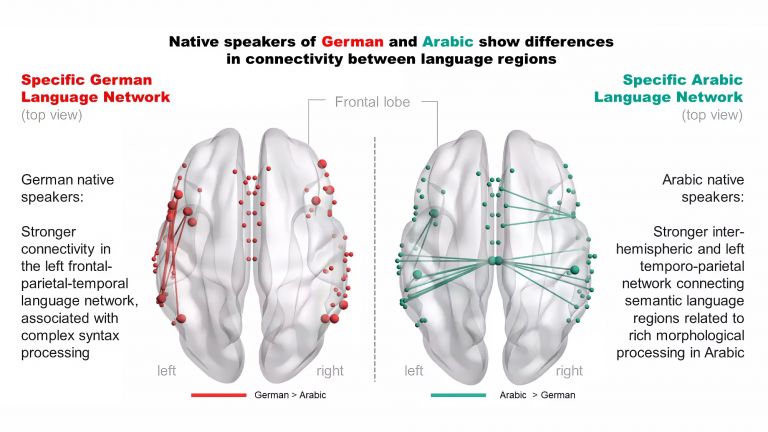

The assumption that emotion and rationality are spatially separated in the brain is widespread among laypeople. Many believe that emotions are located in the right hemisphere and reason in the left. In fact, the right hemisphere appears to be particularly important for processing emotions. After right-sided brain injuries, patients find it more difficult to interpret emotions in other people's faces. However, injuries to the left hemisphere also affect the emotional world: patients often suffer from a so-called catastrophic reaction with deep depression. This suggests that the left hemisphere brightens our emotional state by inhibiting the right hemisphere. Studies with newborns also suggest that the left hemisphere is more active in positive emotions, while the right hemisphere is more active in negative emotions.

However, neuroscientists warn against attributing complex phenomena such as emotions to a single hemisphere of the brain. This is because both hemispheres are involved in almost all functions, albeit to varying degrees. In split-brain patients, whose neural connection between the two hemispheres has been severed, the relative strengths of the two brain hemispheres can be clearly observed: the left hemisphere is better at searching for causes and explanations. In contrast, the right hemisphere has a special talent for spatial-visual tasks.

The hormonal and vegetative reactions to the feeling of fear and the automatic behavioral programs that follow serve to ensure survival. By releasing stress hormones, the pituitary gland enables the threatened person to act more quickly and efficiently. The basal forebrain additionally increases alertness and arousal. The autonomic system is activated via the brain stem: blood pressure and the frequency of breathing and heartbeat increase, muscles contract – the frightened person is ready to flee or fight. To prevent injuries from distracting humans or animals, the brain stem also reduces pain perception. Finally, the brain stem also provides automated behavioral programs, such as facial expressions of fear or cries of fear, to call for help from others.

“It was just before midnight,” reports 48-year-old Martha Kristensen, "my husband and I were standing in front of our hotel in Naples. Suddenly, someone kicked me in the back of the knee from behind, threw me to the ground, and grabbed me and my backpack. I was terrified that they would kidnap me and drag me into a car. My heart was racing, I was frozen with fear. It happened so fast that I couldn't even scream for help."

Source of emotions

Fear: a feeling that everyone knows, even if they have been spared terrible experiences like that of architect Martha Kristensen (name changed by the editors). We are afraid of heights, plane crashes, dogs, our boss. When we feel this emotion, we feel it from the tips of our toes to the top of our heads. Our heart beats faster, our hands tremble, we sweat, our stomach rumbles.

Scientists have long been interested in the structures in the brain that cause us to freeze in fear or anxiety. Numerous studies on animals and humans have been conducted over the past decades to answer this question. And so it comes as no surprise that the mechanisms of fear are now among the most thoroughly researched circuits of our emotional apparatus.

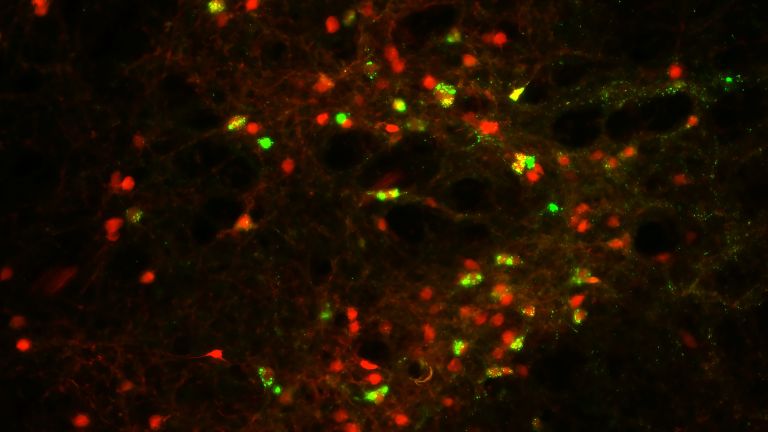

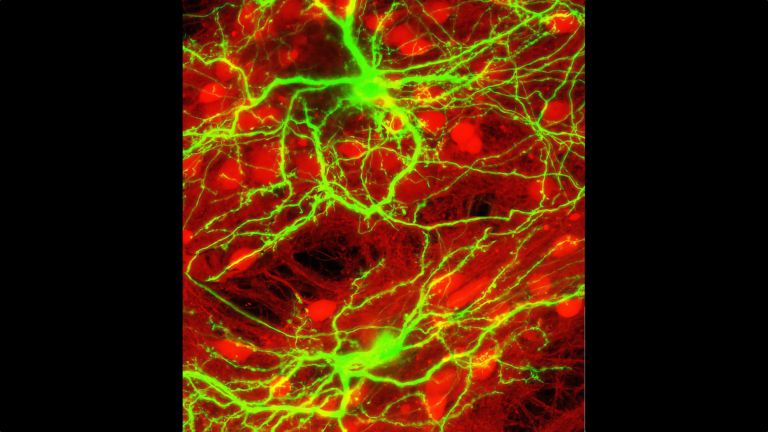

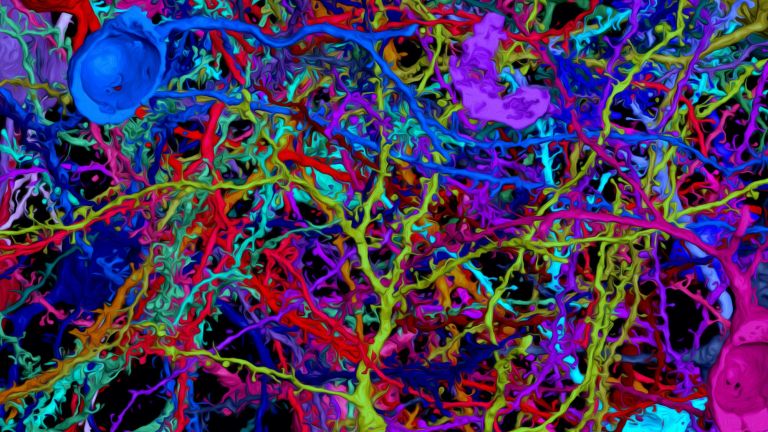

It is now proven that one structure in particular plays a major role in this process: the amygdala (almond kernel). It is part of the limbic system, which is believed to play an important role in emotion processing (see info box). The amygdala also plays a central role in aggression. It consists of two almond-shaped clusters of nerve cell bodies located in the center of the human brain, one in the left and one in the right temporal lobe, directly in front of the hippocampus.

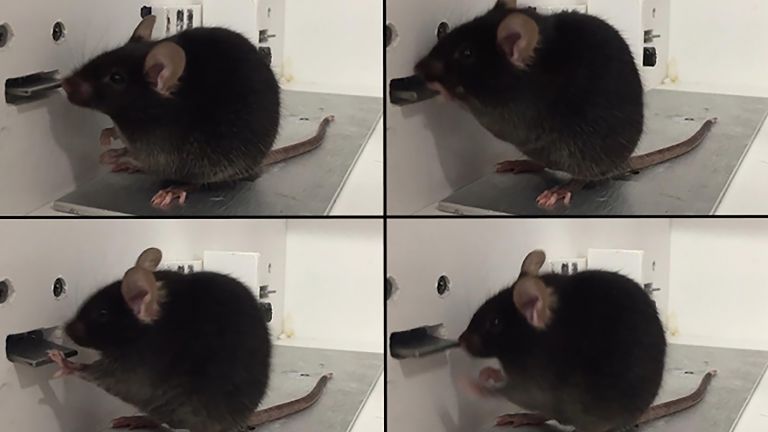

Even the smallest injuries to the structures of the amygdala are enough to completely change an animal's behavior: “Wild-caught birds,” reported biologist Richard Phillips of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute, “which normally try to escape in panic, suddenly become completely calm.” Laboratory rats with a lesion of the amygdala curiously explore sedated cats. Conversely, electrical stimulation of small cell clusters in the amygdala is enough to make cats cower fearfully from mice or react angrily with raised fur, hunched backs, and dilated pupils – depending on which area of the amygdala was stimulated.

Innate and learned fears

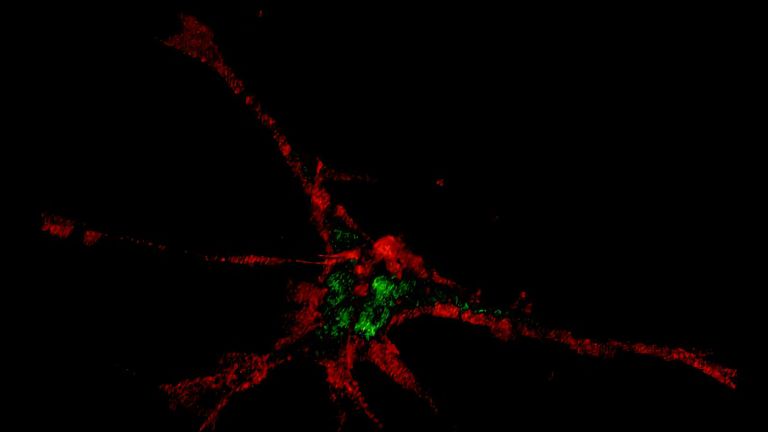

The amygdala thus serves as an alarm system for animals and humans. Within a few milliseconds, it evaluates situations and assesses dangers. Some sights, sounds, or smells trigger fear from birth or after a single encounter. For example, laboratory rats that have never lived in the wild are afraid when they hear the cry of an owl or smell a predator.

Some fears are not innate, but very easy to acquire. Monkeys, for example, fear snakes as soon as they observe another monkey reacting with fear to a reptile. The amygdala of primates reacts similarly sensitively to negative facial expressions of others. Evolutionarily, such innate fears or tendencies toward fear are of great advantage to the individual creature: for example, if a rat quickly flees when it hears an owl hooting, it may save its life.

However, even stimuli that have long been perceived as neutral or positive can become associated with danger through learning processes and later trigger fear themselves. If a neutral stimulus occurs simultaneously or shortly before an unpleasant stimulus such as pain, the fear triggered by the unpleasant stimulus rubs off on the neutral stimulus. The sounds Martha Kristensen heard immediately before she was kicked in the back of the knee were stored by her amygdala as threatening. “When I hear footsteps behind me today,” she says, “especially at night, I still feel afraid. I turn around or walk faster.”

Recommended articles

Circuitry of fear

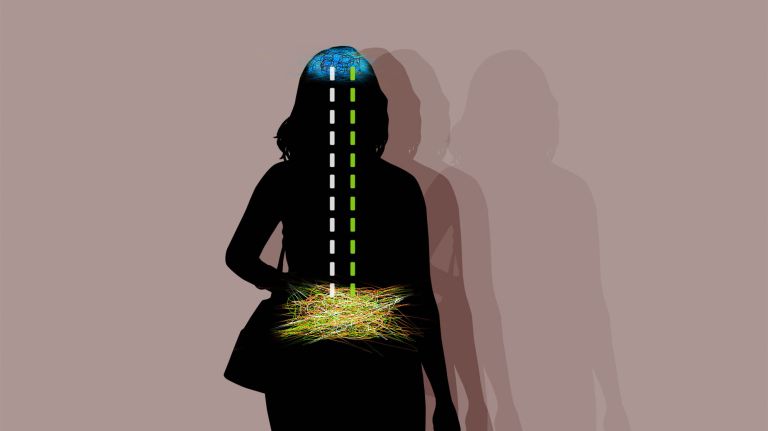

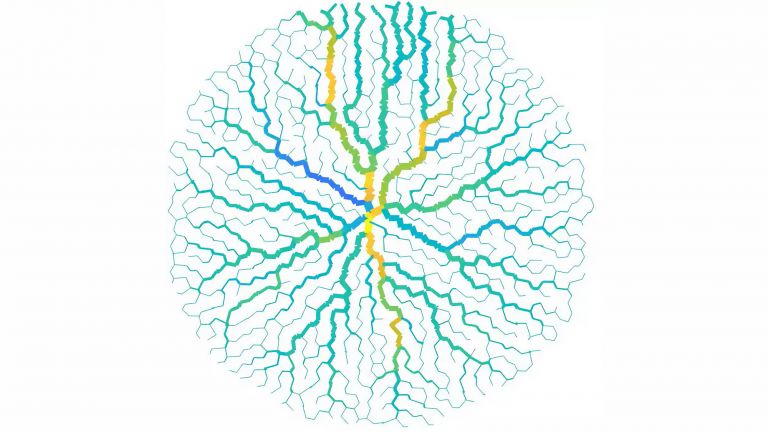

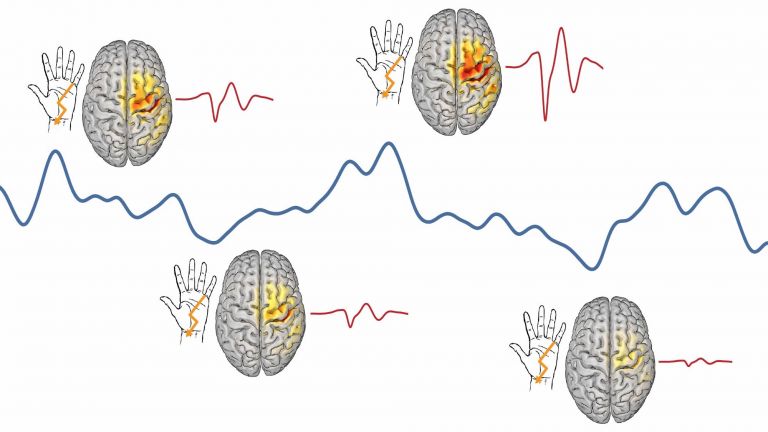

But how does the brain actually know whether a situation is dangerous? Neuroscientist Joseph LeDoux of New York University has described the underlying mechanisms as a fear circuit that sends information to the amygdala in two ways: one fast, rough, and error-prone, and one slow but verified by precise analysis.

The starting point is always the thalamus. This part of the diencephalon forms the gateway to consciousness and is an important central hub for messages from the sensory organs. When it receives an emotional stimulus, such as a loud noise, it forwards a rough sketch of the sensory impression directly to a small group of cells (“fear-on” neurons) in the lateral amygdala.

When these cell clusters are activated, the information flows on to the central core of the amygdala. This is where the defensive behavior programs are activated. This triggers physical fear responses, as Martha Kristensen describes: “Everything happened so fast, I was afraid, my heart was racing, I was frozen with fear. I only felt the many bruises afterwards.” Thanks to this thalamo-amygdala connection, animals and humans can react to danger at lightning speed (see info box).

The brain stem and cerebral cortex are also informed. The brain stem triggers automatic behavioral responses, which can range from freezing to fleeing to attacking. The cerebral cortex is responsible for the emotional experience of fear.

False alarms and their correction

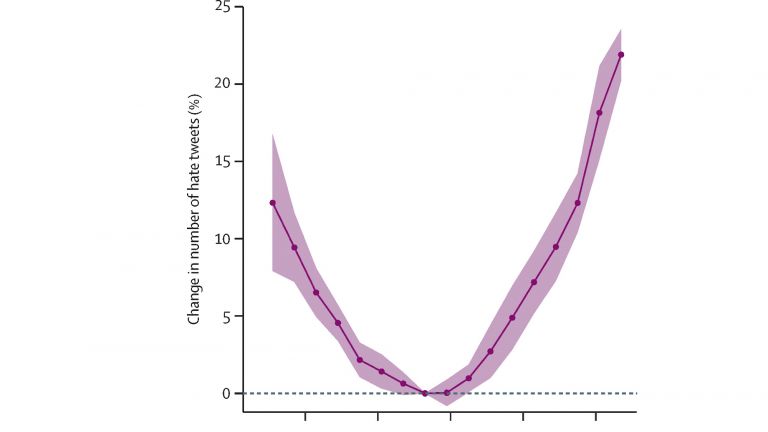

However, this sensitive, rapid pathway of the fear circuit occasionally triggers false alarms: for example, when we are startled by our own shadow, the sound of a whistle, or the sight of a snake-shaped stick. In addition to the shortcut described by LeDoux as “quick and dirty,” there is also the so-called “high road” of cognitive processing leading from the thalamus to the amygdala.

On this conscious route, sensory information from the thalamus first reaches the cortex and the hippocampus. There, the impressions are analyzed in more detail before they reach the amygdala. The sensory areas of the neocortex enable us to perceive fear stimuli in a more differentiated way and, for example, to distinguish a woman's tiptoeing steps from a man's heavy footsteps. However, the brain needs time to do this: it takes twice as long for the information to reach the amygdala via the cortex as it does via the direct route from the thalamus.

In addition, the hippocampus also brings conscious memories of unpleasant or anxiety-provoking situations into play via the slow route. When Martha Kristensen hears footsteps close behind her, for example, she sees images of the attack in Naples again. LeDoux describes it this way: " The hippocampus is crucial in recognizing a face as that of your cousin. But it is the amygdala that adds that you don’t really like him!"

Just like the neocortex, the hippocampus is also connected to the amygdala. It can curb fear by analyzing characteristics with more nuance and assessing a stimulus as harmless. This is why we sometimes get scared of our own shadow – and then, just a split second later, breathe a sigh of relief and laugh because we realize it was a false alarm.

First published on August 15, 2012

Last updated on September 11, 2025