On the Trail of emotions

It's like the question of whether the chicken or the egg came first: How are feelings, physical reactions, and cognitive assessments of a situation interrelated when it comes to emotions? There are conflicting theories on this in the history of emotion research.

Scientific support: Prof. Dr. Alfons Hamm

Published: 18.07.2018

Difficulty: intermediate

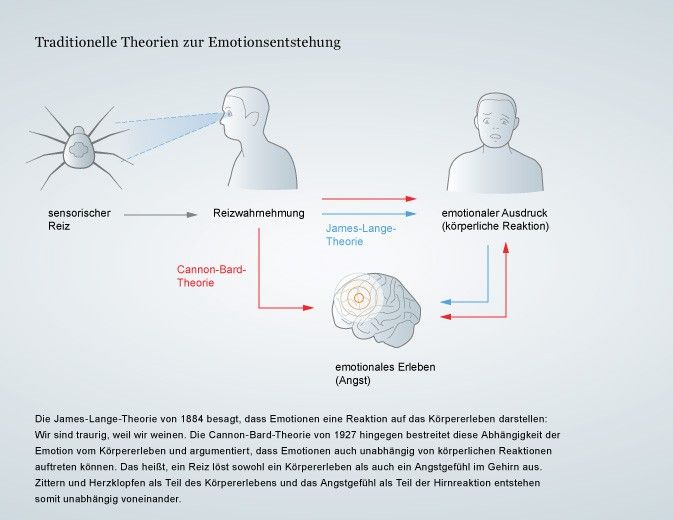

- The James-Lange theory from 1884 postulates that we feel emotions because we are physically aroused. According to this theory, we are angry because we feel our blood pressure rise and our heart “is in our mouth.”

- The James-Lange theory was experimentally disproved in 1927/28 by US physiologists Walter Cannon and Philip Bard. The Cannon-Bard theory states that emotions and physical reactions occur simultaneously and independently of each other.

- The two-factor theory from the 1960s assumes that feelings only arise when, in addition to a physical reaction, there is also a cognitive evaluation of the situational trigger: we are anxious because we perceive a situation as threatening.

- According to the neuroscientific concept, emotions arise via two separate pathways: a stimulus that has not yet been fully processed can trigger initial behavioral adjustments via the amygdala before we become fully aware of it. On the other hand, conscious cortical networks (such as memories stored in the cortex) can trigger physical accompaniments of emotions.

It seems like a clear-cut case: we cry because we are sad. We evaluate a situation, it triggers a feeling in us, and then the body reacts – right? To the American psychologist and philosopher William James, this “order of reason,” as he called it, did not seem so clear-cut. Don't emotions sometimes occur independently of an assessment? For example, some people panic at the sight of spiders, even though they know that these useful eight-legged creatures are harmless in this country.

First the body, then consciousness: the James-Lange theory

In his 1884 essay “What is an emotion?”, James therefore put forward a theory – almost simultaneously with a paper by the Danish physiologist Carl Lange, who, independently of James, formulated a very similar thesis. The ideas of the two researchers are now known as the James-Lange theory of emotions. According to this theory, a stimulus does not first trigger the emotion, but immediately results in physical processes, known as physiological activation. Only in the second step does the emotion arise, as we perceive the change in our body: “Reason suggests that we are sad because we cry, angry because we strike, fearful because we tremble,” James writes in his essay.

As he himself struggled with feelings of depression, James turned his theory into a prescription: “Thus the sovereign voluntary path to cheerfulness, if our spontaneous cheerfulness be lost, is to sit up cheerfully, to look round cheerfully, and to act and speak as if cheerfulness were already there.” Recent experiments on the effect of facial expressions on emotional experience show that this approach can actually work. Studies have also shown that humans can perceive their own physical sensations, such as excitement or trembling, at least to some extent.

Body and consciousness: the Cannon-Bard theory

Nevertheless, the theory was heavily criticized at the beginning of the last century. In a paper published in 1927, American physiologist Walter Cannon argued his case with experiments on animals whose spinal cords had been severed. Although their bodily sensations were largely eliminated, they still showed obvious emotional reactions – a fact that, according to the James-Lange theory, should not have been possible. Another point of criticism was that the physical state did not allow for reliable conclusions about emotions. After all, palpitations, sweating, and gastrointestinal disorders occur not only in anxiety, but also in other emotions such as anger – or for completely different reasons, such as fever.

Cannon and later his colleague Philip Bard concluded that neither the conscious feeling could depend on the physical reaction nor vice versa. According to the Cannon-Bard theory, both arise simultaneously: on the one hand, the stimulus is transmitted to the cortex, where it triggers the feeling, and on the other hand, to the autonomic nervous system, where it causes the physiological reaction. However, current findings contradict Cannon and Bard's arguments: studies have shown that the physiological reactions to fear and anger can indeed be distinguished. And patients who are paralyzed from the neck down report that the intensity of their feelings has decreased.

If emotion is not triggered solely by physical reactions, as James and Lange believed, but the body still appears to have an influence on our emotional life, contrary to the theory of Cannon and Bard, how can we explain the origin of our feelings?

Recommended articles

The importance of evaluation: two-factor theory

Another front of discussion was opened in the early 1960s by the American social psychologists Stanley Schachter and Jerome E. Singer. In addition to feelings and physical arousal, they also brought cognition into play, i.e., thoughts, interpretations, and evaluations. Schachter's two-factor theory states that emotions require not only a physical reaction – which can be the same for every emotion, as it only determines the intensity of the feeling – but also cognition: the situation must be interpreted as triggering an emotion.

Schachter and Singer conducted a complex experiment that confirmed this theory. However, repetitions by other scientists yielded contradictory results. Nevertheless, some aspects of the two-factor theory are considered established. One example is what is known as arousal transfer: if a test subject is physically activated by sport or an emotion they have just experienced, this increases the intensity of subsequent, different emotions.

Resolving the contradictions: the concept of unconscious emotions

The controversy surrounding the sequence of cognition and emotion continued, and further theories emerged. In 1989, however, the American neuroscientist Joseph LeDoux succeeded in resolving the seemingly contradictory positions with a neurobiologically based model of emotion generation.

According to this model, emotional stimuli are processed in two different ways in the brain. The shortest route allows information to reach the brain at lightning speed and activate defensive or appetitive behavioral adjustments without the need for conscious emotional experience. In addition, there is a second, slower pathway via the cerebral cortex, where the trigger is cognitively evaluated, and

only then is the emotional response activated.

The amygdala plays a key role in all of this. It filters out relevant environmental events and initiates physical adaptation processes in each case. All of this takes place – at least initially – without conscious emotional experience. According to LeDoux, the brain knows much more about the world than we do. Finally, LeDoux noted that all of the processes described are not always dependent on external stimuli, but can also be triggered solely by brain activity, such as the activation of “memory networks” in the cortex.

This provides a coherent picture of how simple and more complex emotions can arise – independently of consciousness, but involving cognitive processes. Multi-stage reactions can also be explained in this way: for example, when the immediate heart palpitations at the sight of a spider are followed by relief when it becomes clear that it is only a rubber toy. Nevertheless, it can be assumed that this briefly outlined concept will be further developed.

Further reading

Brown, M. Th, Fee, E.: Walter Bradford Cannon. Pionier Physiologist of Human Emotions. American Journal of Public Health. 2002; 92 (10):1594 — 1595 (zum Text).

First published on August 14, 2011

Last updated on September 11, 2025