Conscious Emotions

Emotions are generated in the limbic system, which is not subject to consciousness. Only when the cerebral cortex is activated do feelings become conscious. Whether fear, joy, or hatred is felt depends on which areas of the cortex are active.

Scientific support: Prof. Dr. Alfons Hamm

Published: 11.08.2025

Difficulty: intermediate

- In neuroscience, a distinction is often made between emotions, i.e., the physical reaction to an external stimulus, and feelings, in which the brain processes the body's reactions.

- Only Emotions that reach the cerebral Cortex are perceived as conscious feelings.

- Fear, anger, happiness, and sadness activate different areas of the brain. The patterns are almost identical in women and men.

Emotions

Neuroscientists understand "emotions" to be complex response patterns that include experiential, physiological, and behavioral components. They arise in response to personally relevant or significant events and generate a willingness to act, through which the individual attempts to deal with the situation. Emotions typically occur with subjective experience (feeling), but differ from pure feeling in that they involve conscious or implicit engagement with the environment. Emotions arise in the limbic system, among other places, which is a phylogenetically ancient part of the brain. Psychologist Paul Ekman has defined six cross-cultural basic emotions that are reflected in characteristic facial expressions: joy, anger, fear, surprise, sadness, and disgust.

Cortex

cortex cerebri

Cortex refers to a collection of neurons, typically in the form of a thin surface. However, it usually refers to the cerebral cortex, the outermost layer of the cerebrum. It is 2.5 mm to 5 mm thick and rich in nerve cells. The cerebral cortex is heavily folded, comparable to a handkerchief in a cup. This creates numerous convolutions (gyri), fissures (fissurae), and sulci. Unfolded, the surface area of the cortex is approximately 1,800cm².

In 1848, a worker named Phineas Gage was seriously injured in an accident involving gunpowder in the USA: an iron rod shot into his face below his left eyebrow and pierced his brain. Amazingly, he survived and suffered no functional damage except for the loss of an Eye. However, he was no longer the same person he had been before the accident: unlike before, he was now considered disrespectful, impatient, unreliable, and prone to anger. The cause was severe damage to his prefrontal cortex.

Eye

bulbus oculi

The eye is the sensory organ responsible for perceiving light stimuli – electromagnetic radiation within a specific frequency range. The light visible to humans lies in the range between 380 and 780 nanometers.

Cortex

cortex cerebri

Cortex refers to a collection of neurons, typically in the form of a thin surface. However, it usually refers to the cerebral cortex, the outermost layer of the cerebrum. It is 2.5 mm to 5 mm thick and rich in nerve cells. The cerebral cortex is heavily folded, comparable to a handkerchief in a cup. This creates numerous convolutions (gyri), fissures (fissurae), and sulci. Unfolded, the surface area of the cortex is approximately 1,800cm².

Being able to say “I'm afraid” or “I love you” requires that these feelings enter our consciousness. However rich a person's emotional life may be, this is the exception rather than the rule. This is because although the Limbic system in the brain constantly generates emotions, we usually don't notice them. Only when the signals from this system, which consists of several structures and developed early in the evolution of mammals, reach the evolutionarily younger cerebral Cortex are fear, love, hate, joy, anger, or sadness consciously perceived. This, if at all, only happens at the end of a complex process.

Emotions

Neuroscientists understand "emotions" to be complex response patterns that include experiential, physiological, and behavioral components. They arise in response to personally relevant or significant events and generate a willingness to act, through which the individual attempts to deal with the situation. Emotions typically occur with subjective experience (feeling), but differ from pure feeling in that they involve conscious or implicit engagement with the environment. Emotions arise in the limbic system, among other places, which is a phylogenetically ancient part of the brain. Psychologist Paul Ekman has defined six cross-cultural basic emotions that are reflected in characteristic facial expressions: joy, anger, fear, surprise, sadness, and disgust.

Limbic system

The limbic system is a functional unit in the brain. It consists of interconnected structures, primarily in the cerebrum and diencephalon. The structures assigned to the system vary depending on the source, but the most important components are the hippocampus, amygdala, cingulate gyrus, septum, and mammillary bodies. The limbic system is involved in autonomic and visceral processes as well as in mechanisms of emotion, memory, and learning. Some authors mistakenly reduce the limbic system to the emotional world by referring to it as the "emotional brain."

Cortex

cortex cerebri

Cortex refers to a collection of neurons, typically in the form of a thin surface. However, it usually refers to the cerebral cortex, the outermost layer of the cerebrum. It is 2.5 mm to 5 mm thick and rich in nerve cells. The cerebral cortex is heavily folded, comparable to a handkerchief in a cup. This creates numerous convolutions (gyri), fissures (fissurae), and sulci. Unfolded, the surface area of the cortex is approximately 1,800cm².

Feelings in the head

Anyone who is wandering through the forest and suddenly comes face to face with a bear actually experiences fear twice – via two different mechanisms. The first analyzes the situation imprecisely, but at lightning speed: information from the sensory systems is transmitted directly to the Amygdala via the thalamus. This part of the limbic system, also known as the amygdala because of its almond-like shape, assesses in a few milliseconds whether the stimulus is harmful or beneficial to us. When encountering the bear, the amygdala complex concludes that it is a potential danger. So, it triggers the appropriate physical defensive response via the Hypothalamus and Brain stem the heart begins to beat faster, blood pressure rises, sweat breaks out. The purpose of all this is to prepare for a fight or to initiate flight. All this happens before we even realize that we are afraid.

The second pathway runs from the thalamus to the cerebral Cortex and is significantly slower. However, this system processes the situation in greater detail. It involves the visual cortex, whose activation allows us to consciously perceive the bear, and the hippocampus, from which Memory content is retrieved – the brain compares the current situation with previous experiences. The Prefrontal cortex (PFC) also plays an important role. It processes Emotions by integrating them into the overall picture and draws conclusions about the best course of action. It is also the region of the brain where emotional stimuli from the Limbic system are converted into conscious feelings.

The importance of the PFC for a person's personality and emotional life is demonstrated by the case of Phineas Gage, a worker who lost this part of his cerebral cortex in an accident (see info box). Once the dangerous situation has been thoroughly analyzed, the frontal cortex sends its information back to the limbic system for reassessment. And, if necessary, modification.

Amygdala

corpus amygdaloideum

An important core area in the temporal lobe that is associated with emotions: it evaluates the emotional content of a situation and reacts particularly to threats. In this context, it is also activated by pain stimuli and plays an important role in the emotional evaluation of sensory stimuli. Inaddition, it is involved in linking emotions with memories, emotional learning ability, and social behavior. The amygdala is part of the limbic system.

Hypothalamus

The hypothalamus is considered the center of the autonomic nervous system, meaning it controls many motivational states and regulates vegetative aspects such as hunger, thirst, and sexual behavior. As an endocrine gland (which, unlike an exocrine gland, releases its hormones directly into the blood without a duct), it produces numerous hormones, some of which inhibit or stimulate the pituitary gland to release hormones into the blood.In this function, it also plays an important role in the response to pain and is involved in pain modulation.

Brain stem

truncus cerebri

The "trunk" of the brain, to which all other brain structures are "attached," so to speak. From bottom to top, it comprises the medulla oblongata, the pons, and the mesencephalon. It transitions into the spinal cord below. It is a center for vital functions such as breathing and heartbeat and contains ascending and descending pathways between the cerebrum, cerebellum, and spinal cord.

Cortex

cortex cerebri

Cortex refers to a collection of neurons, typically in the form of a thin surface. However, it usually refers to the cerebral cortex, the outermost layer of the cerebrum. It is 2.5 mm to 5 mm thick and rich in nerve cells. The cerebral cortex is heavily folded, comparable to a handkerchief in a cup. This creates numerous convolutions (gyri), fissures (fissurae), and sulci. Unfolded, the surface area of the cortex is approximately 1,800cm².

Memory

Memory is a generic term for all types of information storage in the organism. In addition to pure retention, this also includes the absorption of information, its organization, and retrieval.

Prefrontal cortex

Prefrontal cortex

The prefrontal cortex (PFC) forms the front part of the frontal lobe and is one of the brain's most important integration and control centers. It receives highly processed information from many other areas of the cortex and is responsible for planning, controlling, and flexibly adapting one's own behavior. Its central tasks include executive functions, working memory, emotion regulation, and decision-making. In addition, the PFC plays an important role in the cognitive evaluation and modulation of pain.

Emotions

Neuroscientists understand "emotions" to be complex response patterns that include experiential, physiological, and behavioral components. They arise in response to personally relevant or significant events and generate a willingness to act, through which the individual attempts to deal with the situation. Emotions typically occur with subjective experience (feeling), but differ from pure feeling in that they involve conscious or implicit engagement with the environment. Emotions arise in the limbic system, among other places, which is a phylogenetically ancient part of the brain. Psychologist Paul Ekman has defined six cross-cultural basic emotions that are reflected in characteristic facial expressions: joy, anger, fear, surprise, sadness, and disgust.

Limbic system

The limbic system is a functional unit in the brain. It consists of interconnected structures, primarily in the cerebrum and diencephalon. The structures assigned to the system vary depending on the source, but the most important components are the hippocampus, amygdala, cingulate gyrus, septum, and mammillary bodies. The limbic system is involved in autonomic and visceral processes as well as in mechanisms of emotion, memory, and learning. Some authors mistakenly reduce the limbic system to the emotional world by referring to it as the "emotional brain."

frontal

An anatomical position designation – frontal means "towards the forehead," i.e., at the front.

Cerebral cortex controls emotions

This has been demonstrated in studies of people with arachnophobia. In their brains, the Visual cortex and Prefrontal cortex are highly active when the eight-legged creature comes into view. The Amygdala also fires excessively. If such patients manage to get their phobia under control through behavioral therapy, researchers measure, contrary to what might be expected, not less activity in the amygdala after treatment – instead, the prefrontal Cortex works harder: the phobic patients have learned to reevaluate the fear-inducing stimulus “spider” and to assess its danger differently.

Neuroscientist António Damásio distinguishes between Emotions and feelings: emotions, he says, are physical reactions that follow a stimulus and are visible to the outside world; feelings, on the other hand, arise when the brain analyzes and consciously perceives the body's reactions. Cats without a cerebral cortex can still show anger as an expression of emotion by hissing and trying to scratch. This was demonstrated by physiologist Walter Cannon (1871–1945) as early as the 1920s.

However, such animals are no longer able to feel the actual emotion of anger: their rage is directed at nothing in particular and is not aimed at the source of the stimulus that makes them angry. Furthermore, as Cannon called it, the sham rage immediately dissipates when the stimulus is removed. This suggests that the cerebral cortex is responsible for controlling the emotional response to a stimulus. In other words, it directs the response toward the cause or inhibits it if the cause is not relevant enough.

Visual cortex

The visual cortex refers to the areas of the occipital lobe that are involved in processing visual information. These include the primary visual cortex and the associative visual cortices V1 to V5. According to Brodmann, the visual cortex comprises areas 17, 18, and 19.

Prefrontal cortex

Prefrontal cortex

The prefrontal cortex (PFC) forms the front part of the frontal lobe and is one of the brain's most important integration and control centers. It receives highly processed information from many other areas of the cortex and is responsible for planning, controlling, and flexibly adapting one's own behavior. Its central tasks include executive functions, working memory, emotion regulation, and decision-making. In addition, the PFC plays an important role in the cognitive evaluation and modulation of pain.

Amygdala

corpus amygdaloideum

An important core area in the temporal lobe that is associated with emotions: it evaluates the emotional content of a situation and reacts particularly to threats. In this context, it is also activated by pain stimuli and plays an important role in the emotional evaluation of sensory stimuli. Inaddition, it is involved in linking emotions with memories, emotional learning ability, and social behavior. The amygdala is part of the limbic system.

Cortex

cortex cerebri

Cortex refers to a collection of neurons, typically in the form of a thin surface. However, it usually refers to the cerebral cortex, the outermost layer of the cerebrum. It is 2.5 mm to 5 mm thick and rich in nerve cells. The cerebral cortex is heavily folded, comparable to a handkerchief in a cup. This creates numerous convolutions (gyri), fissures (fissurae), and sulci. Unfolded, the surface area of the cortex is approximately 1,800cm².

Emotions

Neuroscientists understand "emotions" to be complex response patterns that include experiential, physiological, and behavioral components. They arise in response to personally relevant or significant events and generate a willingness to act, through which the individual attempts to deal with the situation. Emotions typically occur with subjective experience (feeling), but differ from pure feeling in that they involve conscious or implicit engagement with the environment. Emotions arise in the limbic system, among other places, which is a phylogenetically ancient part of the brain. Psychologist Paul Ekman has defined six cross-cultural basic emotions that are reflected in characteristic facial expressions: joy, anger, fear, surprise, sadness, and disgust.

Recommended articles

The search for the seat of emotions

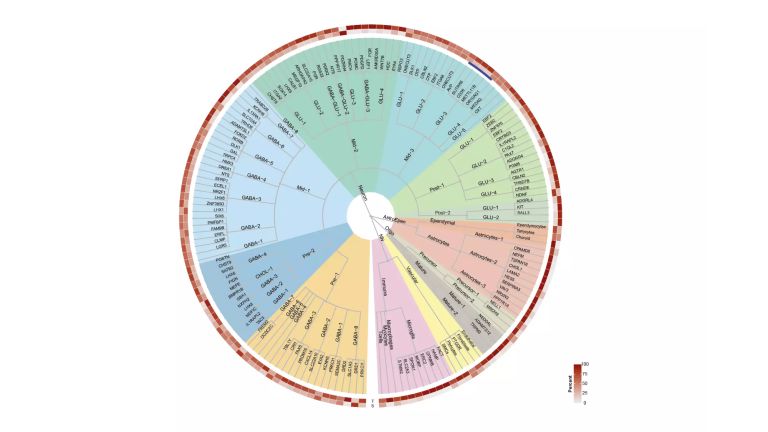

At least in humans, control goes a step further. By activating the cerebral cortex, Emotions can be consciously perceived, with the result that we better understand what is happening to us. On the other hand, emotional experience can also be influenced by thoughts. António Damásio at the University of Southern California investigated where exactly which conscious emotions are processed in the brain: The emotion researcher asked test subjects to imagine situations in which they had felt happiness, sadness, anger, or fear, and looked under their skulls using functional magnetic resonance imaging, an imaging technique that makes brain activity visible.

The result: different areas of the cerebral Cortex were activated depending on the type of emotion. When feeling happy, the right cingulate gyrus, the left insula, and the right somatosensory cortex were particularly active, while the left Cingulate gyrus fired less than normal. When the test subjects were sad, the insular cortex on both sides was more active than usual, as was the anterior cingulate gyrus; the posterior cingulate gyrus, on the other hand, remained silent. Anger and fear also resulted in very specific activation patterns. However, there is no single area for anger and no specific region for happiness. Rather, the neural networks that are activated by certain emotions overlap to a large extent and are also active, at least in part, when other emotions are experienced. Colleagues criticize Damásio's conclusions from this study as rather speculative.

Surprisingly, there is little difference between men and women when it comes to where they process emotions in the brain: several studies have confirmed that the neural activation patterns are comparable in both sexes, regardless of whether the emotions are positive or negative.

Emotions

Neuroscientists understand "emotions" to be complex response patterns that include experiential, physiological, and behavioral components. They arise in response to personally relevant or significant events and generate a willingness to act, through which the individual attempts to deal with the situation. Emotions typically occur with subjective experience (feeling), but differ from pure feeling in that they involve conscious or implicit engagement with the environment. Emotions arise in the limbic system, among other places, which is a phylogenetically ancient part of the brain. Psychologist Paul Ekman has defined six cross-cultural basic emotions that are reflected in characteristic facial expressions: joy, anger, fear, surprise, sadness, and disgust.

Cortex

cortex cerebri

Cortex refers to a collection of neurons, typically in the form of a thin surface. However, it usually refers to the cerebral cortex, the outermost layer of the cerebrum. It is 2.5 mm to 5 mm thick and rich in nerve cells. The cerebral cortex is heavily folded, comparable to a handkerchief in a cup. This creates numerous convolutions (gyri), fissures (fissurae), and sulci. Unfolded, the surface area of the cortex is approximately 1,800cm².

Cingulate gyrus

gyrus cinguli

The cingulate gyrus is an important part of the limbic system in the cerebrum. This strip of cortex runs medially in the cerebrum, directly above the corpus callosum. Among other things, it is involved in emotions and memory. Through its connections to limbic and autonomic centers, it can also influence autonomic responses (e.g., heart rate, blood pressure). The anterior (front) region in particular is also associated with attention, motivation, error monitoring, and emotion regulation.

posterior

A positional term – posterior means "towards the back, located at the rear." In relation to the nervous system, it refers to a direction towards the tail.

We like what comes from the right better

Everyone knows from their own experience that emerging Emotions can influence how attentive we are and thus how well we perform a task. Various experiments confirm this: for example, when test subjects are asked to name the font color of a word, phobic individuals have more difficulty when the term of the object they fear appears. Surprisingly, feelings can be changed simply by the direction of gaze: In 1987, US researcher Roger Drake reported for the first time that men who had to turn their gaze to the right to look at a photo generally liked the image better than men who had to look to the left. Two years later, Dutch scientists discovered the same phenomenon in women. The explanation for this is the theory that when a test subject looks to the right, the left Hemisphere of the brain is activated, which is more involved in positive feelings, while the right hemisphere tends to generate negative feelings.

Even stimuli that are so brief that we are not consciously aware of them influence our feelings and moods. Researchers at Tilburg University in the Netherlands showed a group of test subjects frightening images, such as rabid dogs. They presented a second group with disgusting scenes, such as a dirty toilet. The control group was only shown neutral images, such as chairs. The images were only shown for a short time, so that their content escaped the conscious Perception of the test subjects. And yet they still had an effect. Those who viewed the disgusting images subsequently refused to take part in a food test, while those who had seen the frightening scenes, even if not consciously, did not feel like watching a horror movie. However, the test subjects were unable to explain why they had made these decisions. Feelings are often beautiful, sometimes painful, and occasionally annoying. And they have a great power over our behavior. Whether they enter our consciousness or not.

Emotions

Neuroscientists understand "emotions" to be complex response patterns that include experiential, physiological, and behavioral components. They arise in response to personally relevant or significant events and generate a willingness to act, through which the individual attempts to deal with the situation. Emotions typically occur with subjective experience (feeling), but differ from pure feeling in that they involve conscious or implicit engagement with the environment. Emotions arise in the limbic system, among other places, which is a phylogenetically ancient part of the brain. Psychologist Paul Ekman has defined six cross-cultural basic emotions that are reflected in characteristic facial expressions: joy, anger, fear, surprise, sadness, and disgust.

Hemisphere

The cerebrum and cerebellum each consist of two halves – the right and left hemispheres. In the cerebrum, they are connected by three pathways (commissures). The largest commissure is the corpus callosum.

Perception

The term describes the complex process of gathering and processing information from stimuli in the environment and from the internal states of a living being. The brain combines the information, which is perceived partly consciously and partly unconsciously, into a subjectively meaningful overall impression. If the data it receives from the sensory organs is insufficient for this, it supplements it with empirical values. This can lead to misinterpretations and explains why we succumb to optical illusions or fall for magic tricks.

Further reading

- Damasio, A., et al.: Subcortical and cortical brain activity during the feeling of self-generated Emotions. Nature Neuroscience. 2000; 3(10):1049 – 1056 (zum Abstract).

Emotions

Neuroscientists understand "emotions" to be complex response patterns that include experiential, physiological, and behavioral components. They arise in response to personally relevant or significant events and generate a willingness to act, through which the individual attempts to deal with the situation. Emotions typically occur with subjective experience (feeling), but differ from pure feeling in that they involve conscious or implicit engagement with the environment. Emotions arise in the limbic system, among other places, which is a phylogenetically ancient part of the brain. Psychologist Paul Ekman has defined six cross-cultural basic emotions that are reflected in characteristic facial expressions: joy, anger, fear, surprise, sadness, and disgust.

First published on August 23, 2011

Last updated on September 11, 2025