Learning the Meaning of Fear

People are not born afraid of bosses, dogs, or spiders – we learn many fears over the course of our lives. The brain is ideally equipped for this: everything it fears, it remembers particularly well.

Scientific support: PD Dr. Thomas Seidenbecher

Published: 21.08.2025

Difficulty: intermediate

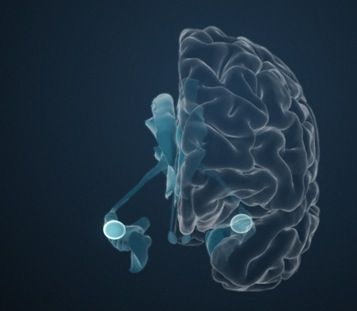

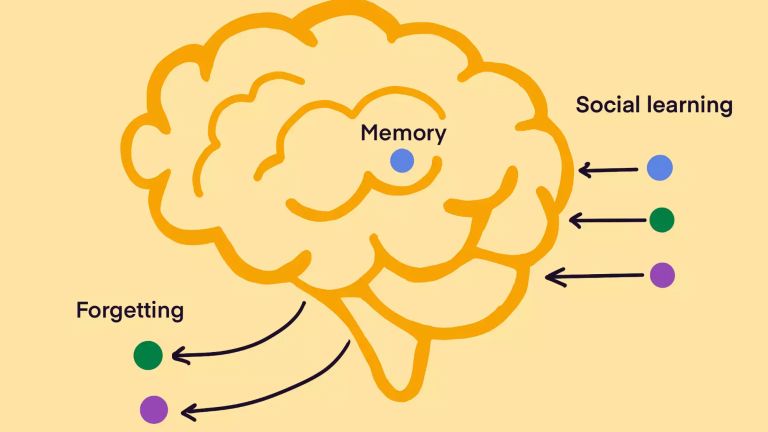

- In fear conditioning, a threatening stimulus is linked to a previously neutral stimulus in the amygdala.

- The amygdala, in conjunction with other brain regions such as the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex, is responsible for linking memories with emotions.

- Emotional events are burned particularly deeply into our memory thanks to various neurotransmitters released by the brain.

“I should like to learn how to shudder” longs the boy in a fairy tale by the Brothers Grimm, titled “The story of the youth who went forth to learn what fear was” – a wish familiar to patients with Urbach-Wiethe desease. This is because the vessels within the amygdala calcify in those affected, causing the surrounding cells to die. As a result, their sense of fear is usually severely impaired.

In the journal “Current Biology”, Justin Feinstein and colleagues from the University of Iowa reported on a patient (abbreviated SM): In a pet store, she reached out with interest to snakes and would have liked to touch a tarantula. Neither the tunnel of horror nor the movie “The Silence of the Lambs” frightened SM. “The unique case of patient SM offers a rare insight into the adverse consequences of living without a functioning amygdala. For SM, the consequences were severe,” wrote the neuroscientists. Because she did not recognize danger, SM was the victim of numerous crimes. Patients without a functioning amygdala often suffer from another deficit: they cannot remember emotional content any better than neutral content.

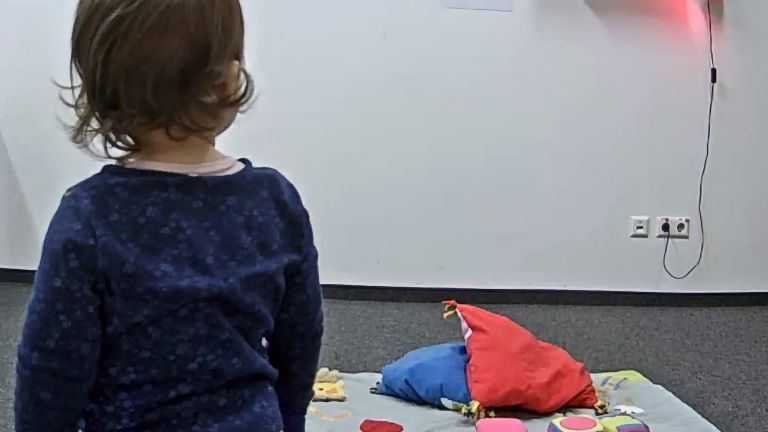

Watson's experiment with Little Albert has often been criticized. Not only because of some methodological shortcomings – Watson only struck the iron bar when Albert reached for the rat – but also because Watson did not cure Little Albert of his fear. At the end of the experiment, Albert was afraid not only of white rats, but also of Santa Claus beards, rabbits, and dogs. However, Albert left the clinic where Watson had discovered him before the psychologist could erase the fear from Albert's emotional memory.

Psychologists and neuroscientists refer to the unlearning of fear as extinction. In extinction, the repeatedly presented conditioned stimulus is not followed by an unpleasant stimulus. Watson would therefore have had to show Albert the white rat several times without simultaneous noise. This is an independent learning process involving the ventromedial prefrontal cortex. Cells from this area of the cortex send fibers to inhibitory cells in the lateral nucleus of the amygdala. In fact, the fear is not erased but merely inhibited. This is why fears can spontaneously reappear, especially under stress.

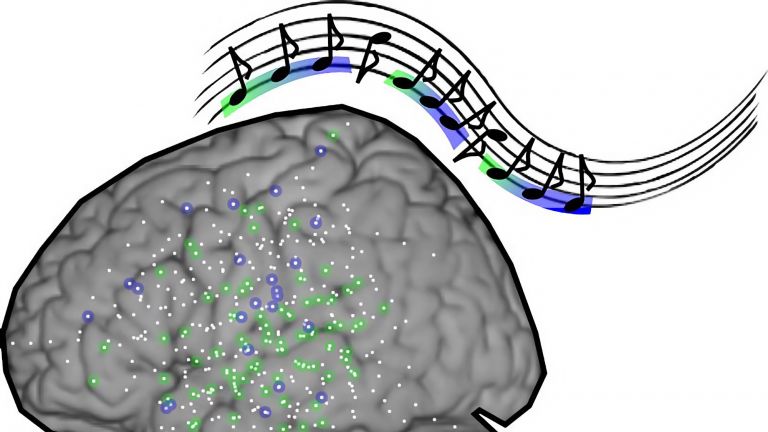

N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors, or NMDA receptors for short, in the amygdala are crucial for emotional memory. If the NMDA receptors in the amygdala are blocked in animals, they cannot acquire new fears through conditioning. What is special about these receptors is that they do not respond when stimulated by a single impulse, but only when a second impulse follows shortly thereafter. Calcium and sodium ions flow into the cell interior through the open receptors, making the cell more sensitive to incoming stimuli. If only the sound occurs the next time, it alone can excite the cell, a process in which so-called long-term potentiation is important.

The excitation of the cells in the lateral nucleus travels via various other nuclei to the exit of the amygdala: the central nucleus. Like a general, the central nucleus issues commands to various structures of the diencephalon and brain stem that trigger innate fear responses to prepare the animal for flight or fight.

Albert screams. The infant turns to the left, falls forward, scrambles to his feet – and finally crawls away as fast as he can. A white rat has frightened the eleven-month-old toddler. Just two months earlier, Albert had trustingly reached out his hand to the animal. But then, in 1920, the little boy became a test subject for psychologist John B. Watson of Johns Hopkins University. Watson would strike an iron bar with a hammer whenever he showed Albert the white rat – until the mere sight of the animal made little Albert cry and flee. Watson had succeeded in teaching Albert to be afraid.

In search of fear

The method, which today seems hardly child-friendly, was already known as fear conditioning from animal experiments: if a fear-inducing stimulus occurs often shortly after or together with a second stimulus, the previously neutral stimulus also generates fear. “I know of no animal that cannot be conditioned,” writes neuroscientist Joseph LeDoux of New York University. Apparently, learned fear has proven useful in evolution – even in humans. The child who fears the stove after getting burned for the first time benefits from this ancient mechanism just as much as the cat that is frightened by the neighbor's dog barking.

Some fears can be learned particularly quickly, such as the fear of snakes: Even in early times, primitive humans were more likely to survive if they feared everything that slithered. But most of today's dangers did not threaten anyone thousands of years ago. If humans were not able to learn fear, they might already be extinct: run over by trains, hit by cars, or killed by electric shocks.

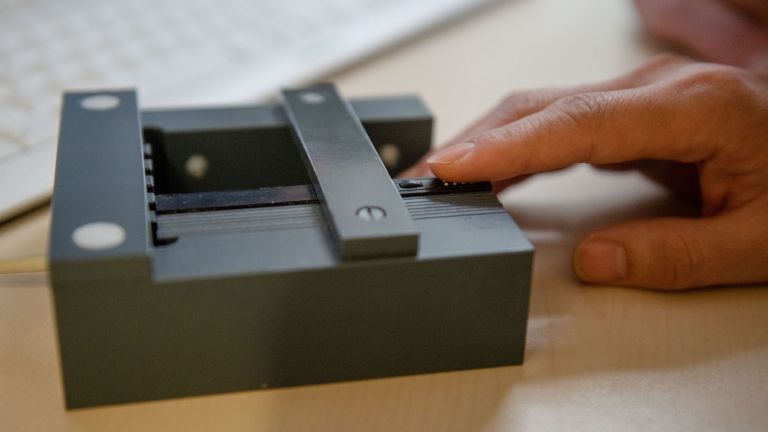

Neuroscientist Joseph LeDoux studied what happens in the brain when we learn and remember fear in rats. He placed the rodents in an experimental box equipped with a loudspeaker and a metal grid floor. When a sound was emitted, the rat simultaneously felt a slight but unpleasant electric shock through the metal grid. As expected, after a short time it reacted to the sound with great fear.

Emotional memory: the amygdala

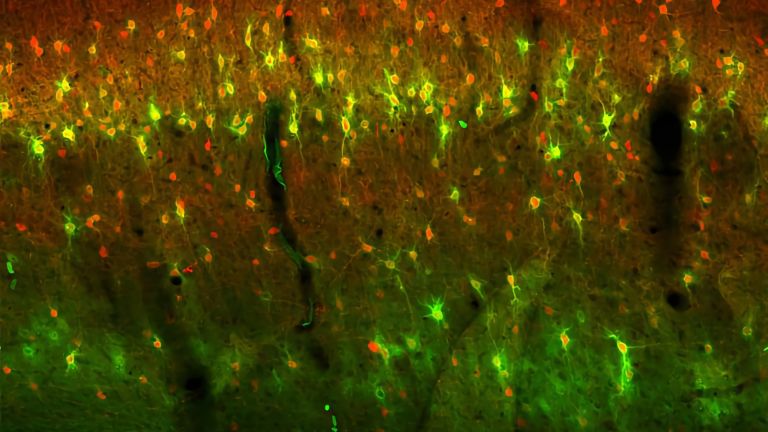

However, when the fear researcher destroyed the rodent's amygdala, the animal suddenly showed no fear. Test animals with damaged amygdalae were unable to learn fear in the first place. In humans with amygdala disorders, it was also found that this area is essential for learning fear (see info box). This area of the brain, also known as the amygdala due to its anatomical structure, is a collection of nuclei deep in the left and right temporal lobes, in close proximity to the hippocampus.

Using imaging techniques, neuroscientists have now also been able to show in humans that the amygdala exhibits increased activity when cold sweat breaks out and the pulse rises. “A rat would never have a panic attack at the news of a stock market crash,” says LeDoux, “and a human being does not normally fear a cat. But the way our bodies react to the news of a stock market crash is very similar to the reaction of a rat when it sees a cat.”

But what exactly happens in the nuclei that make up the amygdala? The thalamus, the sensory control center of the brain, informs the lateral nucleus of the amygdala about both the presentation of the tone and the unpleasant foot shock. At the gate of the amygdala, the information about the signal tone and the electrical stimulus are linked. The cells there are multimodal. This means that they can process information from different sensory organs – i.e., what is seen, heard, but also pain or touch. The fact that the electrical stimulus follows the tone is engraved in the “memory” of the amygdala. (see info box)

Recommended articles

Fear in correction mode

The unpleasant feeling when the tone sounds, the emotional memory, thus arises in the amygdala. However, humans need other brain regions for conscious fear: the respective sensory cortex, the unimodal and polymodal association cortex, and the hippocampus. Like the amygdala, these areas also receive their information from the thalamus. But instead of a rough sketch of what is happening, the cortex receives and processes a detailed recording of the situation. In this way, it can distinguish between similar but differently threatening stimuli, such as two different tones. Sometimes, the cortex's analysis reveals that the fear already welling up in the amygdala is a false alarm: the burglar at the open balcony door was just the curtain blowing in the wind.

Once fears have developed, they usually persist for a long time. This is because fear not only arises in the brain, it also changes it. However, it is also possible to reduce the fear again – with a kind of reverse conditioning (see info box).

When the brain learns a fear, it not only stores precise information about the fear-inducing stimulus, but also remembers the context. After all, a snake on the forest floor is more dangerous than a snake behind glass. The hippocampus in the temporal lobe, which plays an important role in remembering and recalling facts, ensures that we memorize such contextual information.

Emotional memories stick better

There is a reason for linking emotion with memory: the amygdala stamps memories as “important.” That is why people can remember emotionally charged memories better. Remembering frightening experiences is particularly important. After all, avoiding heights, snakes, or brutal fellow human beings can save your life. Therefore, in a frightening situation, the central core of the amygdala activates not only the fight-or-flight system, but also emotional memory. By stimulating the basal nucleus in the basal forebrain, the amygdala causes the neurotransmitter acetylcholine to be released in almost all structures of the cortex. This neurotransmitter helps the brain to absorb as many sensory impressions as possible. In addition, the amygdala ensures that various stress hormones are released. These play an important role when people memorize or remember emotional experiences.

The fact that Albert remembered the clanging of the iron bar as soon as he saw the rat is therefore a mechanism that is as complex as it is vital. In order to learn to fear rats, dogs, or even bosses, humans need not only a malleable amygdala, but also various areas of the cortex and the hippocampus. Only then can we distinguish a dachshund from a Rottweiler, consciously feel fear of dogs, and remember how a Rottweiler once bit our calf.

First published on February 23, 2012

Last updated on August 21, 2025