Playing Tennis in a vegetative State

Patients in a persistent vegetative state appear unresponsive, but behind their blank facades, some are able to play tennis, go for walks, and solve logic puzzles in their minds. With the help of fMRI and EEG, these patients may also be able to communicate again in the future.

Scientific support: Prof. Dr. Niels Birbaumer

Published: 12.06.2025

Difficulty: easy

- Patients in a persistent vegetative state are considered unconscious, but the diagnosis is not accurate in all cases.

- fMRI scans have shown that some patients respond to verbal stimuli with brain activity that is indistinguishable from that of healthy individuals.

- By concentrating on specific mental images, coma patients can answer yes/no questions via the scanner.

- With the help of inexpensive and portable EEG technology, such communication is also possible outside of research centers at the patient's bedside.

In the 1990s, neuropsychologists in Tübingen began developing communication devices for severely paralyzed people who are in a so-called locked-in state. This condition threatens patients suffering from amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), for example, a disease in which the motor nerves degenerate. However, it can also have many other causes.

In complete locked-in syndrome, all muscles, including the eye and respiratory muscles, are paralyzed, but the individuals are cognitively intact. They can hear and understand when someone speaks to them, but they cannot respond. The Tübingen researchers led by Niels Birbaumer use EEG signals that patients learn to control consciously. These signals are derived from their heads and enable them to give yes/no answers on a computer. After microelectrodes were implanted in their brains, these patients were even able to use their brain cells to deliberately formulate entire sentences on the computer.

Since there are many external similarities between patients in a persistent vegetative state and locked-in patients, it was suspected that many patients diagnosed as comatose could be misdiagnosed and in reality might be just – and maybe just predominantly – motor impaired. A test conducted by medical psychologist Boris Kotchoubey on 100 patients in a persistent vegetative state in 2003 revealed EEG signals for complex brain processes in one in four cases. He reports on this in this video.

The distinction between persistent vegetative state and locked-in syndrome is particularly important – and difficult – because, according to current findings, persistent vegetative state can transition into locked-in syndrome. This means that locked-in syndrome can be a stage in the recovery of patients in a persistent vegetative state.

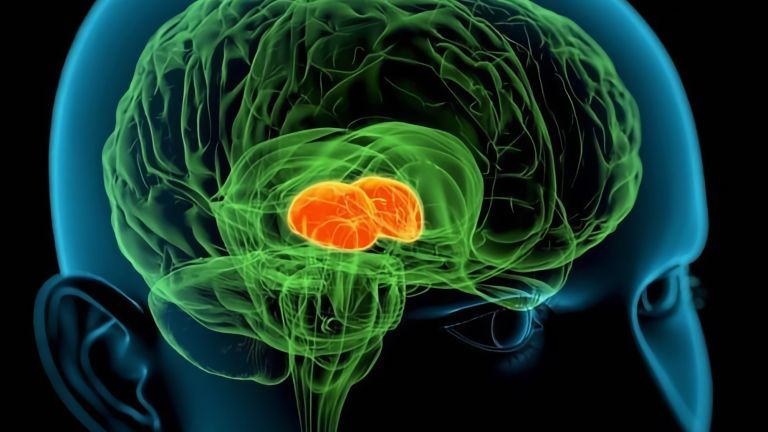

A persistent vegetative state is classically defined as a condition in which the entire cerebrum or large parts of it fail to function, while the functions of the diencephalon, brain stem, and spinal cord remain intact. As a result, those affected go through phases of sleep and wakefulness and can maintain many vital functions such as breathing and digestion, but they do not respond to their environment and are considered unconscious. In technical terms, this condition is also known as apallic syndrome.

In reality, however, there is no such thing as “one” persistent vegetative state, but rather different levels of consciousness impairment. These are measured using the Glasgow Coma Scale , which tests which environmental stimuli a person responds to.

In English-speaking countries, a distinction is made between coma patients in a “vegetative state” or, more accurately, a non-reactive state, who are only capable of unconscious reflexes, and patients in a “minimally conscious state”, who occasionally respond purposefully to stimuli such as sounds, touch, or the presence of relatives. However, the transitions between these categories are fluid.

Kate Bainbridge was 26 years old when she fell into a coma in 1997 after a severe viral infection. A few weeks later, the elementary school teacher opened her eyes and began to breathe on her own again. But nothing else happened. Bainbridge appeared to respond neither to what she saw nor to any sounds and she showed no signs of consciousness. The diagnosis: persistent vegetative state.

Today, despite physical limitations, Bainbridge is able to lead an active life again. The breakthrough – as she sees it today – came four months after her illness, when neuroscientist and psychologist Adrian Owen met her, his first persistent vegetative state patient. Owen, then working at the University of Cambridge in the UK, selected Bainbridge for a new test. He put her in a positron emission tomography (PET) scanner to measure her brain activity. Researchers then showed Bainbridge alternating photos of her relatives and meaningless test images. The result when she saw the family photos was “the beginning of everything,” says Owen. "We were totally amazed. Kate's fusiform gyrus lit up like a Christmas tree – the exact same region that healthy people activate when recognizing faces."

The results of this first experiment motivated Owen, who now works at the University of Western Ontario in Canada (to the website), to devote his scientific career to the search for hidden consciousness – and to give Bainbridge's parents new hope. “We realized that there might be something else that could help her cope with this terrible experience,” they said in a 2006 interview with the BBC. Kate Bainbridge does not remember the experiment, but over the next two years, the young woman's consciousness slowly returned.

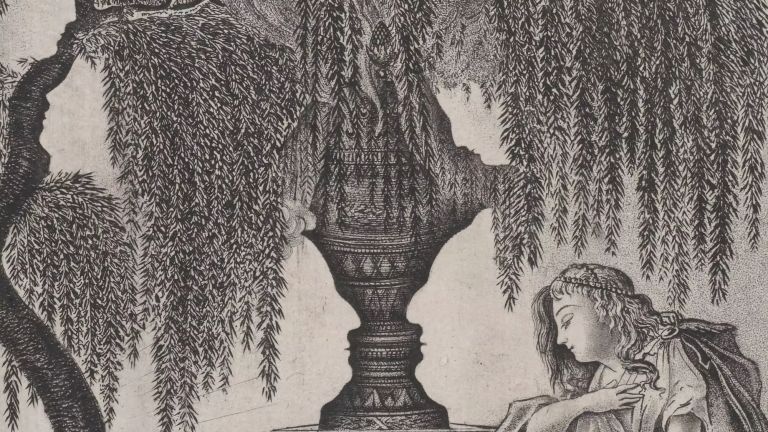

Intact consciousness, lack of interaction

Meanwhile, Owen was looking for ways to prove what he had long suspected, inspired by Bainbridge's case: that consciousness in some coma patients could be largely intact despite a complete lack of interaction with the outside world. There was considerable skepticism among experts. Bainbridge's brain had shown partial functions, but these could not yet be equated with intact consciousness. Owen himself had discovered, for example, that a person does not have to be conscious to process language (to the text). A more complex thinking task was needed, one that was only possible with consciousness.

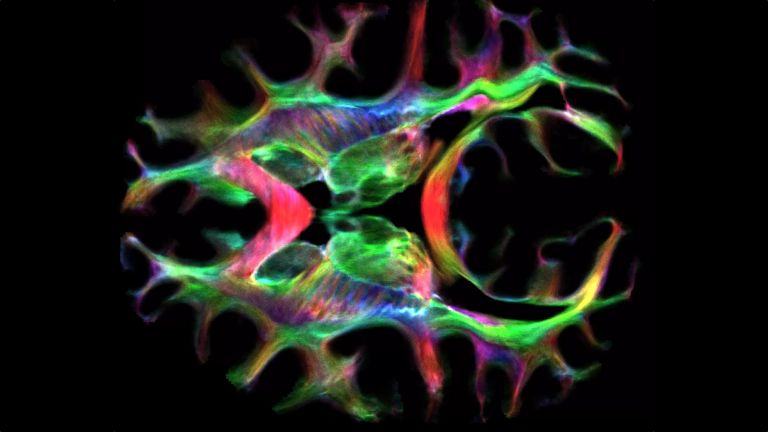

Owen's big chance came nine years later. In the middle of the Wimbledon tennis summer, Owen stole the headlines from the players on the court with a virtual tennis game of a special kind. A 23-year-old patient who was still in a persistent vegetative state five years after a car accident activated the supplementary motor area (SMA) in the fMRI scanner just as reliably as healthy patients when asked to imagine herself playing tennis (to the text). She performed just as well as healthy test subjects when asked to imagine walking through her house: in this case, the parahippocampal gyrus lit up instead. For Owen, these results were clear proof that the patient was conscious despite her external vegetative state. “Healthy patients who are currently unconscious cannot imagine playing tennis on command,” he told thebrain.info.

Although he encountered a great deal of skepticism, Owen increasingly gained respect with his tennis paradigm. He refuted objections that the scan images could be unconscious reflex reactions to the word “tennis” with further experiments. Owen proved that only a test subject's deliberate attempt to imagine themselves performing this activity activated the SMA but not simply hearing someone else say that they were playing tennis. Then, together with Steven Laureys' research group at the University of Liège in Belgium, Owen's team found four more people among 53 coma patients who passed the tennis test.

Patients respond – and solve logic problems

One of them was Patient 23. The man was 27 years old and had been in a persistent vegetative state for over five years following a serious car accident. After his brain produced particularly reliable scan results during the virtual tennis match and house tour, Owen and Laureys asked him to use the two thought experiments in a communication experiment. Patient 23 was asked to answer simple yes/no questions such as “Is your father's name Alexander?” by imagining one of the two activities – such as playing tennis – for ‘yes’ and the other for “no.” Patient 23 passed the test with flying colors on five of the six questions and “answered” just as reliably and correctly as healthy test subjects. The sixth question did not elicit an incorrect response, but rather no response at all – the patient may have fallen asleep.

Patient 23 is not the only case of a person in a persistent vegetative state who has been able to communicate surprisingly complex thought processes via scanner. Just recently, Owen found a 45-year-old man who has been in a persistent vegetative state since a serious car accident in 2008, but who successfully solves logic problems in a brain scanner. The patient and 20 healthy subjects were presented with sentences of varying complexity in which the logical order of the words “house” and “face” was important. The easiest sentences used direct, active statements (“The house follows the face”); the most difficult sentences used negations and passive constructions (“The house is not followed by the face”).

The study participants were asked to think of the object that comes first according to the current sentence. The thought of a house triggers a different activation pattern in the scanner than the thought of a face, so that correct answers can be distinguished from incorrect ones. Except for the most difficult grammatical category – which many healthy participants also got wrong – the patient's scan responses were mostly correct. “This man was able to solve complicated logic problems in the scanner just as well as any of us,” says Owen. “For me, this is proof that patients who appear to be in a persistent vegetative state are actually fully conscious.”

Recommended articles

Wanted: a reliable, mobile communication device

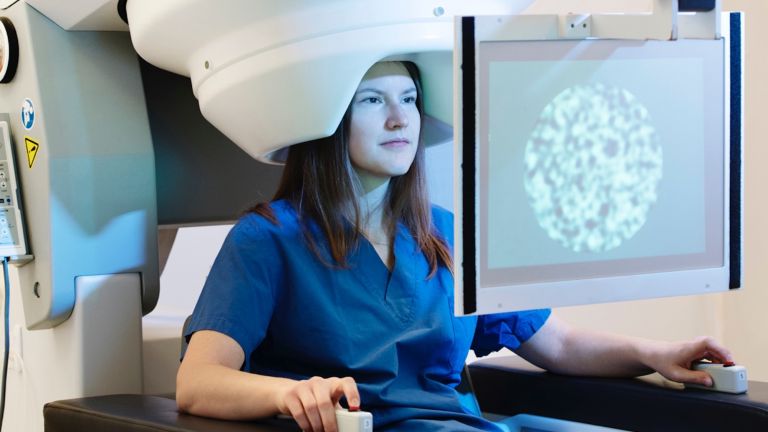

Owen dreams of a reliable and mobile method that would not only enable conscious vegetative state patients in any hospital or nursing home to be correctly diagnosed, but would also enable them to answer simple questions about their well-being and wishes. The technical hurdles are considerable: “Putting patients in the fMRI tube for every question is impractical and impossible in more remote areas,” says Owen. Brain scanners are too expensive, too large, and too immobile, and many patients are not even suitable for fMRI examinations because they suddenly make involuntary movements that interfere with the measurement results. Instead, Owen's team goes on tour with an “EEGeep”. Equipped with customized EEG and analysis technology that is cheaper and easier to transport, the vehicle visits patients on site across the vast expanse of Canada. Instead of tennis and house inspections, the researchers now ask the test subjects to imagine moving either a hand or a foot. Both trigger brain activity that can be easily distinguished with an EEG. Unlike fMRI, an EEG can only measure signals on the surface of the brain. Back in 2011, Owen and Laurey's teams were able to show that three out of 16 coma patients produced reliable EEG signals with the new test that were comparable to those of healthy subjects (to the text). The researchers' next step was to find ways to use this task to answer yes/no questions. Niels Birbaumer's team has finally succeeded in doing this.

Owen believes that patients with hidden consciousness could also be capable of more complex communication in the future with the help of EEG and other brain-machine interfaces. The key to this is the so-called “oddball paradigm”, in which the EEG measures the ‘P300’ wave. This occurs approximately 300 milliseconds after an answer of interest to the user appears in a wealth of uninteresting alternatives. For example, if the user focuses on the word “yes”, its appearance in a matrix of other words triggers the signal. A matrix can contain many possible answers, for example, all the letters of the alphabet.

Such technologies are not easy to use, says Andrea Kübler from the University of Würzburg, who successfully tested an oddball EEG system for coma patients together with Laureys (to the abstract). In patients with impaired consciousness or an unexplained state of consciousness, it is often difficult to read a response, Kübler told dasgehirn.info, especially since attention disorders are often added to the mix. “The concentration and time required to successfully operate more complex systems are factors that such patients often find difficult to muster,” she says. “Yes/no communication will remain the goal for them for the time being.”

Diagnosing persistent vegetative state via brain scan to become routine

Owen believes that it will certainly be years before this becomes a reality. “Before the technologies can be used in clinical practice, they need to become more reliable and easier to use – both for staff and for patients.” As a next step, he urgently wants brain scans to become routine in the diagnosis of persistent vegetative state. In 2009, his team discovered that scans not only detected signs of consciousness that had been overlooked by the behavioral tests previously used as standard in diagnostics, but also that the more the scanner revealed such hidden sparks of thought, the more likely patients were to recover.

The scans may only show the functioning remnants of consciousness, on the basis of which the brain gradually recovers on its own. However, Owen considers another explanation to be more important: “We have noticed time and again that after a positive scan result, the social stimulation our patients receive increases abruptly. People realize that it makes sense to talk to the patient.”

Kate Bainbridge, at any rate, is convinced that the increased attention she received after the scans contributed significantly to her recovery. “The scans found parts of my brain that were functioning,” she wrote in an email in 2007. "It really scares me to think about what would have happened to me without the scans. The images showed other people that it was worth continuing, even though my body wasn't responding."

Further reading

- Birbaumer, N. et al. A spelling device for the paralysed. Nature 1999,398,297- 298

- Chaudhary, U.et. al: Spelling interface uding intracortical signals in a completely locked-in patient enabled via auditory neurofeedback training. Nature Communications,2022, Https//doi.or/10.1038,s-4167-022-28859-8

- Kübler, A et al: A User Centred Approach for Bringing BCI Controlled Applications to End-Users. In: Brain-Computer Interface Systems — Recent Progress and Future Prospects, hg. von Reza Fazel-Rezai, InTechverlag, 2013.

- Monti, MM et al: Willful modulation of brain activity and communication in disorders of consciousness. New England Journal of Medicine, 2010, 362: 579 – 589.

- Owen, AM et al: Detecting Awareness in the Vegetative State. Science, 313, 1402, 2006..

- Kotchoubey B, Lotze M: Instrumental methods in the diagnostics of locked-in syndrome. Restorative Neurology and Neuroscience, 2013;31(1):25 – 40 (zum Abstract).

First published on August 27, 2013

Last updated on June 12, 2025