What is Consciousness?

Are you reading these words? Then there is no doubt about the existence of your consciousness. However, what consciousness actually is, how it is connected to the brain, and whether it can ever be fully explained in neurobiological terms remains a matter of debate.

Scientific support: Prof. Dr. Georg Northoff

Published: 13.06.2025

Difficulty: intermediate

- As soon as we think about something, we do so consciously – consciousness cannot be doubted or argued away. Descartes summed up this insight in his famous statement: “I think, therefore I am.”

- Consciousness is what distinguishes being awake from being in a coma, for example. However, it is always consciousness of something, i.e., it refers to an object. Additionally, many further conceptual distinctions can be made, so that it is sometimes doubted whether “consciousness” as a uniform phenomenon actually exists.

- A well-known explanatory model is the “global workspace theory,” which conceives of consciousness as a central workspace: what happens there is available to all the diverse, largely unconscious processes in the brain.

- For philosophy, consciousness crystallizes the age-old “mind-body problem”: How are the spiritual and the material world – which obviously function according to completely different laws – connected?

- Neuroscience is increasingly venturing into this topic. However, the extent to which consciousness can ever be explained on a purely biological and thus ultimately physical level remains controversial.

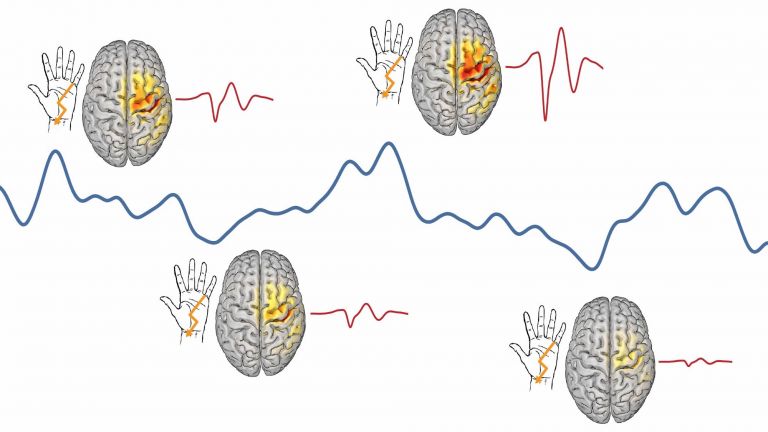

In our everyday experience, attention and consciousness are usually directed toward the same object. Nevertheless, the two are not the same and are not automatically identical. This is demonstrated by clever experiments on the visual system, in which different images for the left and right eye can be used to manipulate what the test subjects consciously see and which image falls on their retina, but never reaches their consciousness. Independently of this, attention can be controlled by giving specific instructions to the test subjects. In this way, researchers led by Masataka Watanabe from the Max Planck Institute for Biological Cybernetics in Tübingen were able to show that the activity of the primary visual cortex depends on attention, but not on whether a particular pattern is consciously seen or not (to the abstract).

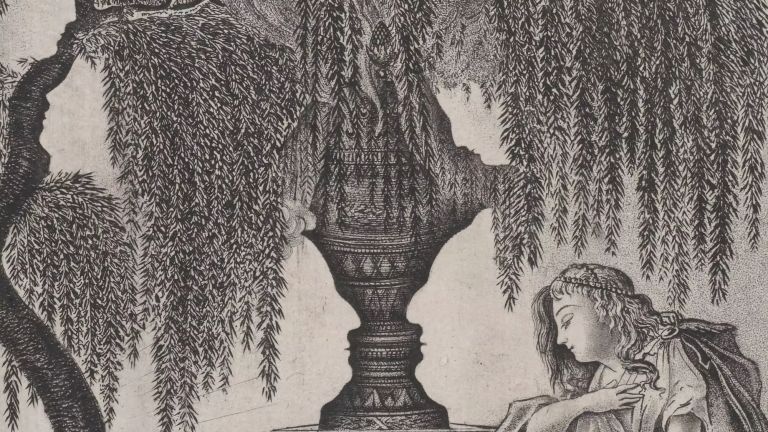

In his “Principles of Psychology,” American psychologist and philosopher William James (1842–1910) characterized consciousness as something continuous that is not composed of individual parts: “It flows.” He therefore chose the river, the stream, as a metaphor for all the changing thoughts, perceptions, emotions, and feelings that occupy us, thus coining the expression “stream of consciousness,” which he regarded as the “ultimate fact of psychology.” This concept later developed into the theory of global workspace.

However, there is no consenus among experts that the stream of consciousness actually exists: British researcher and writer Susan Blackmore criticizes this idea as an illusion.

Regardless, James' term became particularly popular in literature: the “stream of consciousness” narrative style attempts to depict the subjective stream of consciousness as directly as possible in writing, including wild associations and leaps of thought, without punctuation. A famous example of this can be found in James Joyce's “Ulysses.”

There is probably no phenomenon in the universe with which we are as intimately connected as with our own consciousness. Our humanity, our individuality as persons, our complex interaction with our environment would be unthinkable without consciousness. You are reading this text right now: you are thinking about it, making associations with what you are reading – or allowing yourself to be distracted by something else entirely? All of this is happening on the stage of your own personal consciousness.

Nothing in this world can be as certain as the fact that we are conscious at the moment we think about it: “I think, therefore I am.” René Descartes built his entire philosophy on this famous foundation. Everything else can initially be called into question: all sensory impressions could be illusions, our convictions errors, our entire environment a huge hoax – the film “The Matrix” turns this line of thinking, which Descartes also explored, into an opulent story. But consciousness remains a fact.

“One of the most mysterious characteristics of the universe”

For contemporary US philosopher John Searle, consciousness is “the most important aspect of our lives,” as he likes to point out in public lectures. His compellingly clear argument: consciousness is a necessary prerequisite for us to be able to attach meaning to things in our lives. But if, without consciousness, there would be nothing important to us at all, then nothing can be more important than consciousness itself.

As natural and everyday as consciousness is for all of us, the matter becomes complicated upon closer inspection. Neuroscientist Christof Koch, who has been researching this topic for many years, calls consciousness “one of the most mysterious features of the universe.” It is not without reason that philosophers have been grappling with this question for centuries ▸ The Enigma of Consciousness. There is still no accepted scientific definition, and even in everyday use, the term proves to be ambiguous. Neurophilosopher Thomas Metzinger from the University of Mainz, for example, gives five different meanings for the term in the entry “Consciousness” in the Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

The term can refer to whether someone is (fully) conscious or not – for example, because they are asleep ▸ The Night Side of Consciousness or in a coma ▸ Playing Tennis in a Vegetative State. These states of consciousness can be defined objectively and explained, at least in part, by neurobiology. It becomes more difficult with consciousness that is directed toward an object, another person, a fact, or whatever object of perception: When I am aware of a mistake or become aware that there is an unpleasant smell in the air, this is a highly subjective mental process. It takes place solely in my head, and other people can only perceive it if I communicate the matter—consciously or unconsciously, for example by grimacing.

Dance on the stage of subjective experience

This waking consciousness, this dance on the inner stage of subjective experience, begins in the morning when we wake up and continues uninterrupted until we fall asleep – at least it seems difficult to imagine that we are awake without a thought, a feeling, a sensory impression or an activity currently occupying our consciousness. On the other hand, this does not mean that all thoughts, feelings, sensory impressions and activities require consciousness. Rather, psychological and neurobiological research shows that many such processes in our minds can take place unconsciously – and in many cases more effectively and quickly as a result. (See also the articles ▸ If I were a zombie, ▸ What are emotions?)

Further distinctions can be made: Consciousness is not the same as attention (see box “Attention and consciousness”). Consciousness can be directed outward, for example toward objects of perception or our own body, or it can be introspection, the perception of our own mental states. The latter case makes it clear why consciousness is sometimes described as a higher-level or meta-process: while I am spontaneously annoyed by another road user and curse loudly, I can simultaneously observe and reflect on this process at the meta-level – and conclude, for example, that the strong language was rather inappropriate given that my mother-in-law is sitting in the passenger seat.

Conscious reflection by a person on themselves and their identity gives rise to self-awareness and self-consciousness, which have been studied repeatedly by philosophers. This is to be distinguished from self-confidence as used in everyday language: the charisma of a person who is convinced of themselves and their abilities.

Recommended articles

The global workspace theory

Philosopher Ned Block of New York University also distinguishes between consciousness as phenomenal experience, i.e., our subjective experience when we look at a flower or enjoy a touch, for example, and “conscious” in the sense of “available to our thinking and behavioral control.” He also calls the latter “access consciousness,” and this concept is directly linked to a model of consciousness known as the global workspace theory. According to this theory, consciousness is like a stage in the spotlight: only what happens on stage can be seen and heard by the audience sitting in the dark – the many unconscious processes in the brain – and is thus available to them as information for their purposes. However, the many distinctions make it questionable from the perspective of some philosophers whether consciousness is a single, unified phenomenon or rather a collective term for different things. This is also suggested by the fact mentioned in Metzinger's encyclopedia article that many languages have no equivalent for this comprehensive term. This could be one of the reasons why consciousness was not considered a proper subject of research for natural scientists for a long time. Even today, there are still hundreds of pages of current neuroscience textbooks in which the term does not even appear in the index, and John Searle quotes a neuroscientist as saying: “You can certainly research consciousness – but you should definitely have a permanent job first.”

The immortal soul is passé – questions of faith remain

But even without any negative connotations, it remains an extremely difficult field. The question of consciousness crystallizes, in a sense, the old “mind-body problem”: How are the spiritual and material worlds connected? How much reality does the spiritual actually have from an objective point of view? Admittedly, no one in science has advocated the idea of a soul that can exist independently of the body since the death of John Eccles ▸ John Eccles: Across the Gap in 1997. Furthermore, it can be considered proven that the physical-neuronal processes in the brain are a necessary prerequisite for everything spiritual.

However, whether this sufficiently defines the spiritual realm is another question entirely. Is consciousness ultimately just a purely biological process, like everything else that happens in our bodies – admittedly difficult to research because it is a subjective phenomenon, but at least in principle reducible to complex physical processes? For now, this question remains a matter of faith, which empirical scientist Christof Koch sums up as follows: “It is not at all clear whether two brains that are identical from a physical point of view would automatically exhibit the same conscious state.”

Further reading

- “The mind-body problem”: Video interview with Ned Block on consciousness; URL: http://blogs.scientificamerican.com/observations/2013/01/ 28/what-is-consciousness-go-to-the-video/ [as of August 27, 2013]; to the website.

- “The Neuroscience of Consciousness” (textbook chapter, author: Christof Koch); in: Squire, Larry et al. (eds.): Fundamental Neuroscience, Waltham/Oxford (2013)

First published on August 27, 2013

Last updated on June 13, 2025