When Consciousness fails

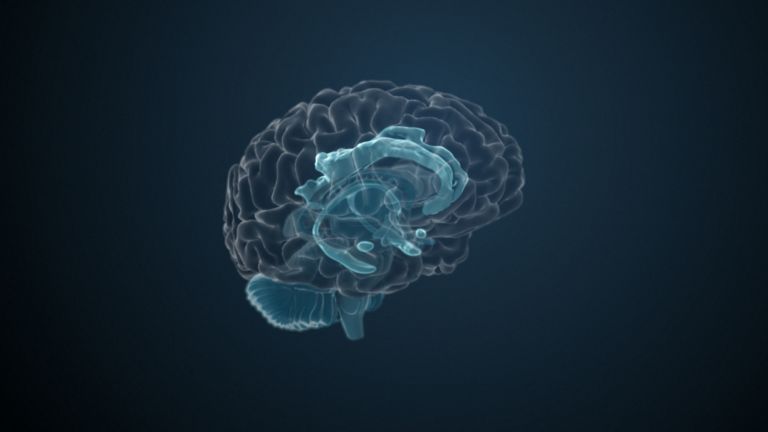

Conscious perception of our surroundings requires several subcortical and cortical brain structures that process and classify sensory impressions. If one of these structures fails, part of our consciousness disappears with it.

Scientific support: Prof. Dr. Niels Birbaumer

Published: 13.06.2025

Difficulty: intermediate

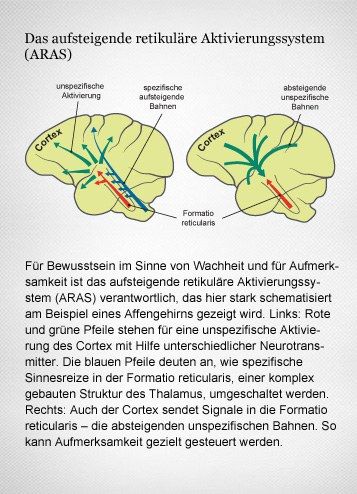

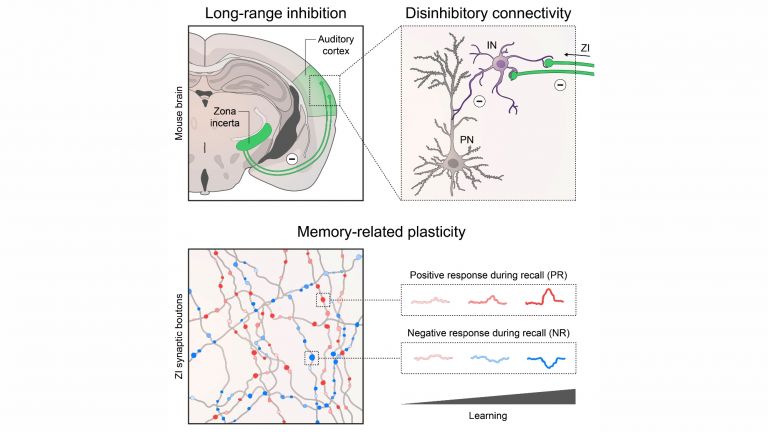

- The ascending reticular activating system (ARAS) maintains numerous nerve connections to the cerebral cortex. These nerve fibers influence the degree of activation, i.e., the alertness of the brain.

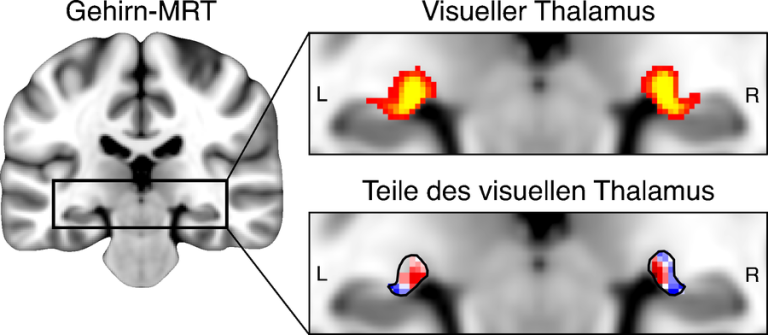

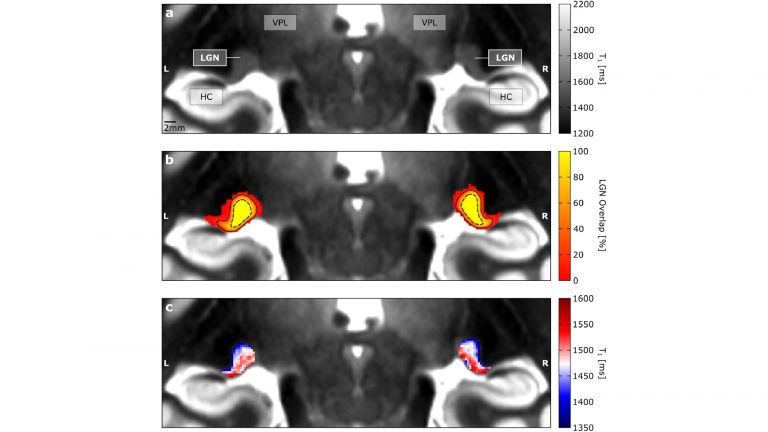

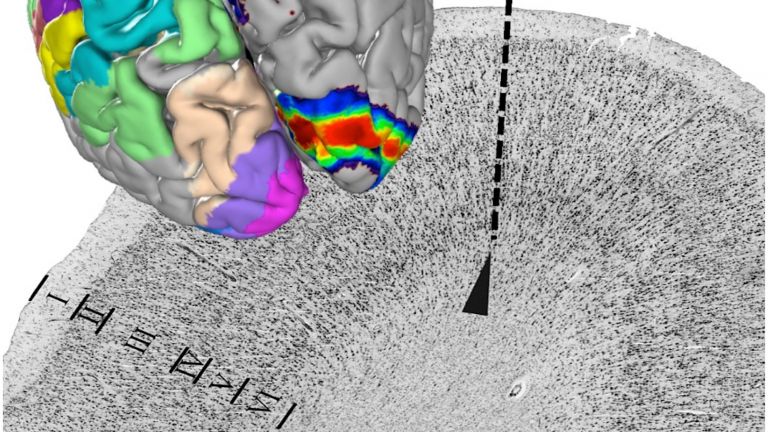

- The thalamus, and in particular the nucleus reticularis thalami, is “the gateway to consciousness”. All sensory impressions except the sense of smell are interconnected in this core area and can be amplified or attenuated by regions of the cerebrum. We call this selective attention.

- In the so-called vegetative or non-reactive state, the person is awake, their reticular activation is functioning, but they have no conscious perception: the connection between the parietal cortex and the prefrontal cortex is destroyed.

- Injuries in the area of the cerebral cortex result in partial loss of sensory impressions. If an entire hemisphere is affected, the person affected only perceives half of their surroundings.

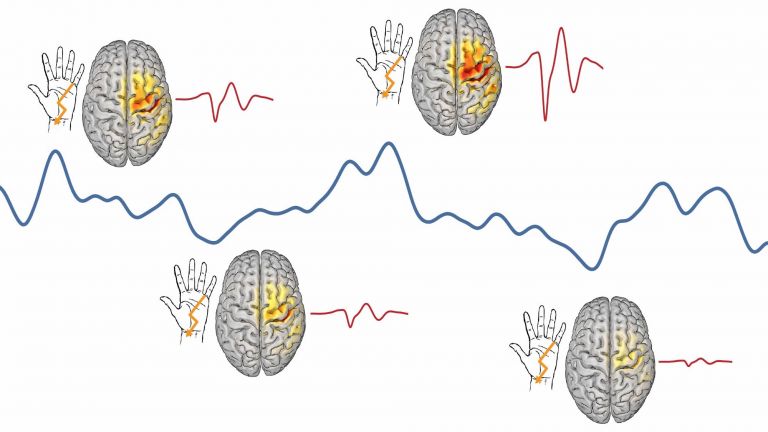

- It is still unclear exactly when the different sensory impressions reach consciousness. The duration of transmission probably depends on the complexity of the sensory impression. In the case of simple stimuli, studies of evoked brain potentials usually assume a duration of approximately 220 milliseconds until the stimuli become conscious.

All sensory impressions must first pass through the thalamus before they can become conscious. But there is one exception: the sense of smell. Its signals take a shortcut directly to the limbic system. There, every nuance of smell arrives unfiltered – whether pleasant or unpleasant. The limbic system then links these with the feelings that prevail during smelling. Smells are therefore a particularly good way of bringing back memories. If the specific scent or smell is perceived again later, the corresponding memory from childhood and youth often resurfaces.

The brain is constantly under fire. Countless sensory impressions bombard our nerve cells every day and must then be evaluated and sorted. Fortunately, not every sensory stimulus makes it into our active consciousness. Just imagine how annoying it would be if every single sensory perception immediately popped into our minds: “I'm warm. It smells like coffee. My colleague is typing on his keyboard. It still smells like coffee...” Instead, we usually only consciously perceive what seems new or important. For example, when our esteemed colleague spills coffee on his keyboard.

However, to access the important information, all the unimportant information must first be briefly evaluated. For our brain to process all the many sensory stimuli, it requires a complex neural system that hierarchically controls our selective attention. The signal “coffee on the keyboard,” for example, requires the thalamus and neocortex to work together. The subcortical motor regions of the basal ganglia – especially the anterior striatum – are also involved in conscious attention, helping to select the appropriate responses.

Well-connected activation system

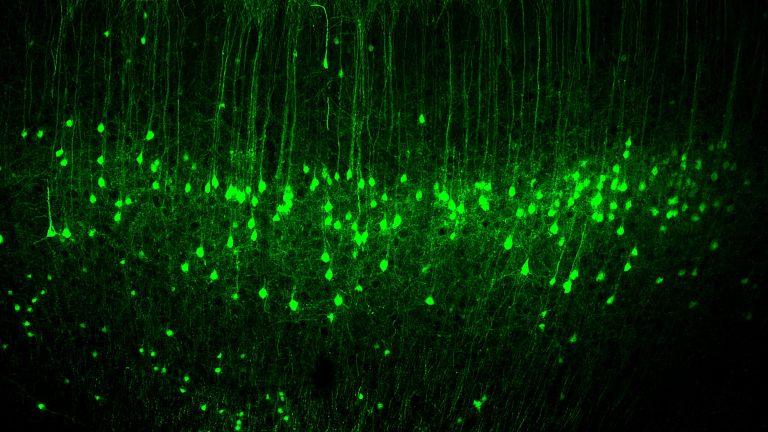

The basis of this system is the ascending reticular activating system, or ARAS for short. This is a network with a large number of nerve nuclei. The ARAS extends from the midbrain via the “thalamus” interface to the cerebrum. The cerebrum itself, with its parietal and prefrontal cortex, is involved in the selection and conscious perception of stimuli and, together with the basal ganglia, determines which response is selected. Therefore, even without feedback on the success of the movements, conscious thinking slowly fails.

This extensive networking is essential because the ARAS influences the activation status of all brain systems. “Its impulses prepare the brain for the reception and processing of new information,” explains Wolf Singer. Attention and the arousal function are primarily mediated by three transmitter systems: norepinephrine, acetylcholine, and serotonin. Norepinephrine and acetylcholine activate the thalamus and thus the receptivity of the cerebral cortex. Serotonin slows down the flow of information. This makes the ARAS indispensable for all types of perception. If it is destroyed, the affected person falls into a coma.

Coma is the most severe form of consciousness disorder. It often occurs in cases of traumatic injury to various parts of the ARAS, but can also occur in cases of extensive lesions of the cerebral cortex, especially after interruption of the connection between the parietal cortex and the prefrontal cortex. In a coma, even strong external stimuli can no longer wake the affected person. No bright light, no loud ringing, not even pain penetrates the cerebral cortex. This is also evident in the electroencephalogram (EEG), which is usually severely and permanently slowed down.

Recommended articles

Mysterious patient

However, it is not only injury to the ARAS that can drastically impair perception. In 2009, a medical case report was published about a young man from Mexico City who initially puzzled the emergency services. The 27-year-old was alert and conscious but appeared to be frozen. He moved in response to pain stimuli, but did not respond to speech, as described in the British Journal of Medical Case Reports.

What had happened? Imaging revealed that the patient had suffered a particularly severe infarction in the thalamus. This region of his brain had almost completely failed. The thalamus is not called “the gateway to consciousness” for nothing: “This is where the nerve pathways of all the sensory organs are switched before they are forwarded to the cerebral cortex,” explains Singer, “so this core area decides which sensory stimuli actually reach the cerebrum.” (For the exception of “smell,” see the box “Smell awakens memories.”)

Every spoken word and every flash of light first passes through the thalamus before we even become aware of it. Accordingly, the rescue workers' questions could hardly penetrate the young man's consciousness. Since his thalamus was no longer functioning properly, the neural signals were stopped here before they could reach the cerebral cortex and thus his consciousness. Only very strong stimuli, such as pain, could pass through the defective core area.

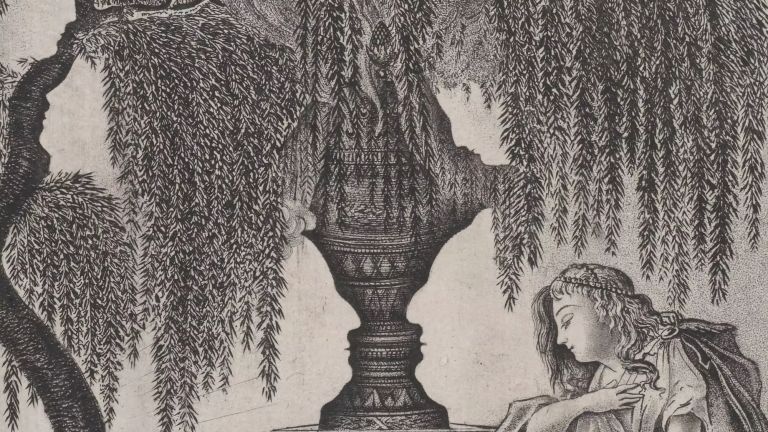

Halved perception

If, on the other hand, the dysfunction affects downstream brain regions, attention is only limited within certain areas. Neglect, for example, shows the consequences that the failure of one hemisphere can have. The term is derived from the Latin word “neglegere,” which means “not knowing” or “neglecting.” Because that is exactly what happens with neglect: half of the environment is ignored.

Neglect usually occurs as a result of a stroke in the right posterior cerebral cortex. However, since sensory information crosses this side on its way to the brain, the perceptual disorder affects the opposite side: everything that happens on the left no longer enters consciousness, while everything that happens on the right is perceived normally. This results in bizarre situations in everyday life that the patient himself does not notice: he only shaves the right side of his face, or only eats the food on the right side of his plate. The left side, on the other hand, is ignored: the vegetables remain untouched and the stubble continues to grow. The same applies to additional unilateral lesions of the basal ganglia for motor function. Here, too, one side is completely neglected: the left leg and left arm are hardly moved, even though they are functionally capable; their existence is ignored.

Further reading:

- Lopez-Serna R et al.: Bilateral thalamic stroke due to occlusion of the artery of Percheron in a patient with patent foramen ovale: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2009 Sep 15;3:7392. doi: 10.4076÷1752−1947−3−7392 (to the text).

First published on August 27, 2013

Last updated on June 13, 2025