Molecular Detectives

We are our memories. But neural firing alone cannot unravel the traces of memory. To do so, researchers must venture into the bubbling cauldron of biochemistry. This is not only relevant for old brains, but especially so.

Scientific support: Prof. Dr. Onur Güntürkün

Published: 01.02.2026

Difficulty: intermediate

- A memory trace consists not only of a network of electrical excitation, but also of changes in proteins, epigenetics, and even in the matrix surrounding the nerve cells.

- One of the central ion channels of learning is the NMDA receptor. It controls the communication of nerve cells via synaptic plasticity.

- The hormone klotho influences the NMDA receptor and protects against cognitive decline. It is considered a promising substance against brain aging.

- The matrix outside the nerve cells also influences learning: during learning, the NMDA receptor initiates its local breakdown and remodeling, allowing a synapse to sprout or become stronger.

- A prominent matrix molecule in the adult brain is brevican – a hot candidate for predicting actual brain age from its level in the blood.

Everyone knows that frustrating moment: You know exactly what you want to say, but the right word just won't come to mind. These small, everyday lapses become more frequent with age. This is because the brain also changes over the years and is no longer as efficient as it once was. At least for most of us.

Especially at the end of life, it becomes particularly clear how important a well-functioning brain is. This is when it no longer absorbs new information as readily or even develops gaps. Against this backdrop, researchers want to find out as much as possible about the mechanisms behind memory. But these mechanisms are proving to be astonishingly diverse. And fragmented.

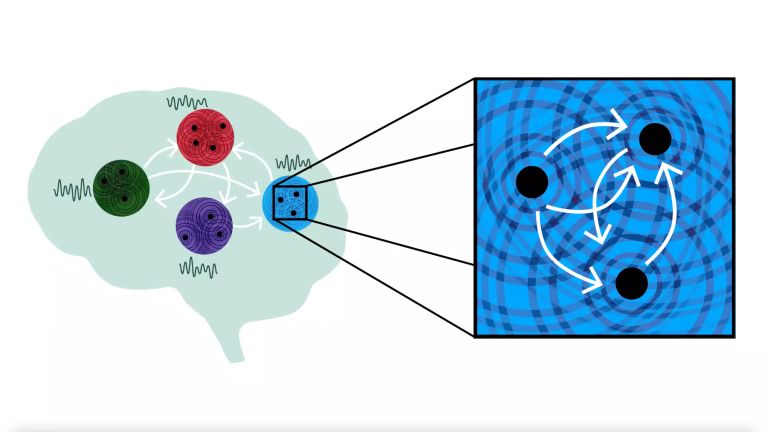

Experts once hoped to read what is stored in the brain from the electrical concert of nerve cells, its frequency and intensity. There is talk of memory traces and thought imprints. Of specific patterns left behind by firing neurons in the brain. A nerve cell concert – one message: the idea is as simple as it is seductive. But if it were that simple, neuroscience would probably be further ahead.

Admittedly, the electrical processes do say something about the areas of the brain involved. It is even possible to make statements about which stimuli a nerve cell responds to. But electrophysiology reveals little about the actual content of thoughts and how they are processed.

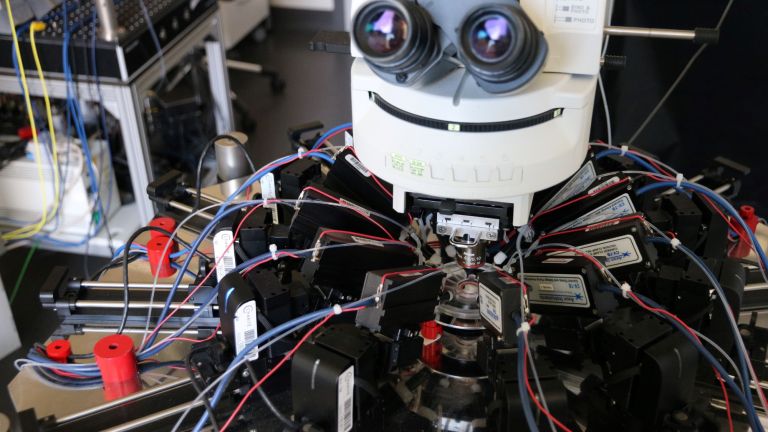

Michael Kreutz, a neuroscientist at the Leibniz Institute for Neurobiology in Magdeburg, says: “What we have learned from basic research, especially in the last twenty years, is that it is more complex than we thought.” He and other researchers are therefore delving ever deeper into the biochemistry of the brain with the aim of one day being able to truly read and understand memory traces.

A thought is much more than a neuron fire

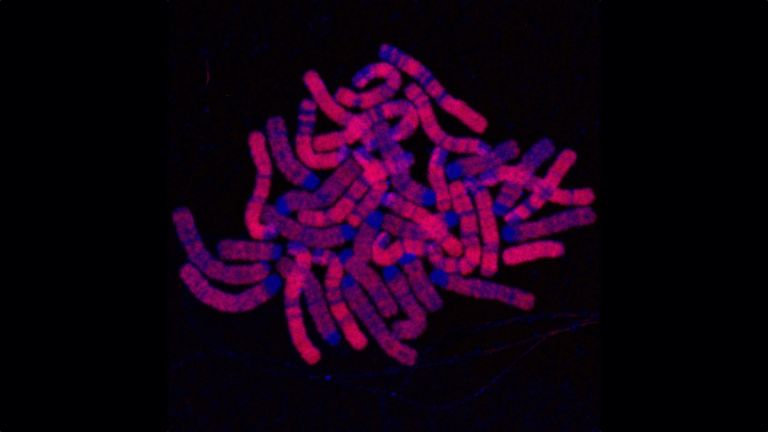

"We want to read out the associated gene expression in each cell in the network of nerve cells that are activated in response to a stimulus. The memory trace is also archived in the cell itself," Kreutz announces. In each affected neuron, the reading pattern - the epigenetics - of hundreds, if not thousands of genes, changes. This is the reason why we retain many things we remember in the long term. “Once you understand that, you understand memory formation. And above all, why it is so stable,” says Kreutz.

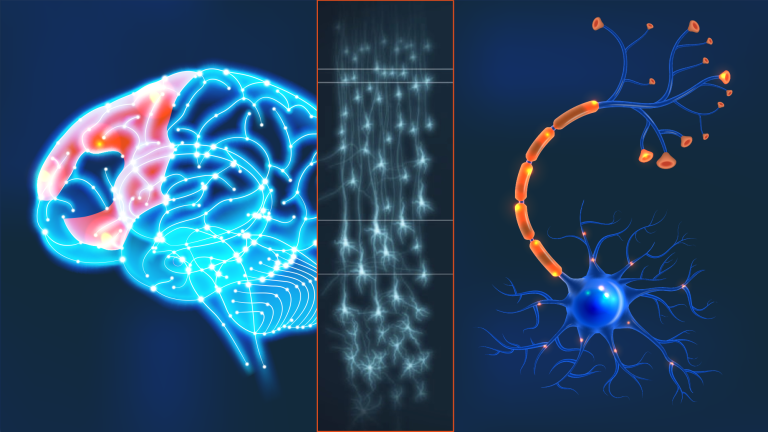

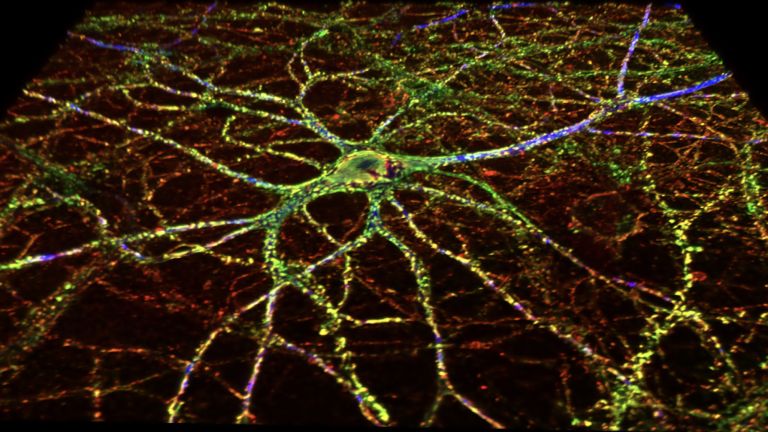

Unraveling the memory trace by recording connectivity and reading gene expression at the single-cell level – “We're not there yet,” he says. The amount of data is huge, the measurement task enormous. This is because a stimulus often activates thousands, if not tens of thousands, of nerve cells in different regions of the brain. The pyramidal cells of the cerebral cortex, for example, which are essential for cognition, can have up to 15,000 synapses, i.e., connections to other nerve cells. Several thousand neurons then communicate with each other.

Using the method of spatial transcriptomics, researchers can in principle determine the expression of genes in each cell, including their location in the tissue. However, this technique cannot read all 21,000 coding genes at the same time, so researchers have to narrow down what they want to look for to a certain extent.

A central ion channel for learning

“We already know important hubs where gene expression is regulated. The transcription factor CREB, for example, is crucial,” says Kreutz. The CREB protein is controlled by the NMDA receptor, an ion channel that is fundamental to learning.

NMDA stands for N-methyl-D-aspartate. “The NMDA receptor is a key molecule,” says Kreutz. When we learn something new, it is activated by the neurotransmitter glutamate binding to the receptor. This causes a powerful influx of calcium into the nerve cell. This in turn causes the content of various proteins in the synapse to change – “in the short, medium, and long term,” emphasizes the neuroscientist. As a result of these changes, the synapse responds differently to the same stimulus than before: it is strengthened or weakened. This transformation of the synapse is believed to be a molecular basis for learning.

The NMDA receptor thus ultimately controls synaptic plasticity, i.e., which nerve cells connect with each other and how intense this exchange is. It therefore plays a key role in the formation of memories and memory. If the receptor is pharmacologically deactivated in individual areas of the brain in mice, this significantly impairs learning.

The NMDA receptor is often affected in neurodegenerative diseases. Even before cognitive impairments become apparent, animal models of dementia show that the two damage proteins characteristic of the disease, amyloid beta and tau protein, reduce the activity of the ion channel. As a result, the transcription factor CREB is no longer produced. “This is a disaster for plasticity, meaning: a disaster for learning,” emphasizes Kreutz.

But even without dementia, the expression of the NMDA receptor changes with age, causing it to lose function. Drugs are therefore now even being tested on this crucial ion channel to see if they could help combat memory loss.

Klotho – a fountain of youth protein in the brain

Almost every protein that is relevant to cognition also appears to affect the NMDA ion channel. Another prominent molecule in basic research is “klotho.”

In 1997, Japanese researchers discovered the protein in mice. Without it, the animals aged prematurely. They developed osteoporosis, calcified arteries, and other typical signs of aging. The pioneers named it after a mythical Greek figure who spins the thread of life: “Klotho”.

It is now clear that the substance is a hormone produced in the adrenal cortex, but also in the brain. It exists in three different variants, which differ slightly in their protein structure.

Klotho cannot cross the blood-brain barrier. Nevertheless, the molecule is considered an interesting candidate in the fight against age-related brain disorders. This is because the level of the alpha form of this protein in the blood naturally decreases with age, and the lower the level, the poorer the cognitive abilities are on average.

When administered artificially, alpha-klotho prolongs lifespan by up to 30 percent in animal experiments. When injected under the skin of older rhesus monkeys once, their cognitive abilities improve in the following two weeks. The substance protects against mental decline and promotes the formation of synapses. Klotho is therefore considered a prominent candidate in pharmaceutical research for slowing down brain aging.

“We have just discovered that klotho also binds to the NMDA receptor and alters the expression of proteins in the synapse, but only in a very specific area of the brain and in certain nerve cells,” Kreutz announces in one of his upcoming publications.

The secret of the matrix: The environment of nerve cells influences cognition

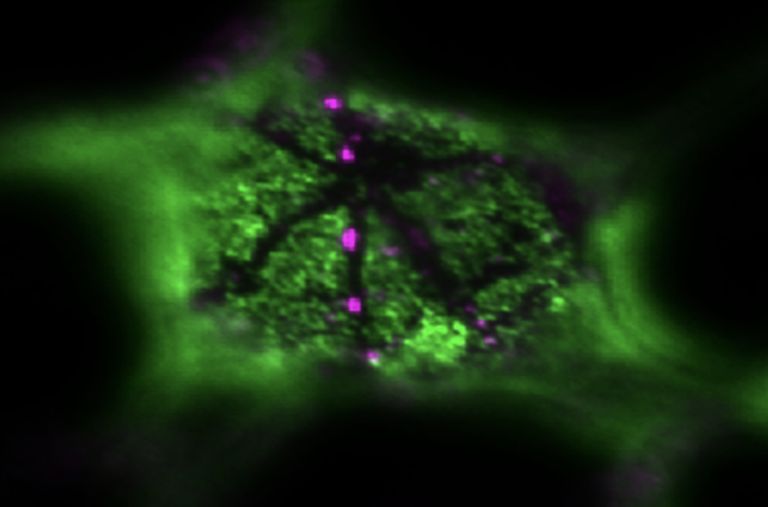

Neurochemist Constanze Seidenbecher from the Leibniz Institute for Neurobiology in Magdeburg was also searching for new proteins in the brain when, in the 1990s, almost simultaneously with other scientists, she discovered brevican – a protein with long sugar chains. Such proteoglycans were already well known from other tissues, but not from the brain. In other organs, they typically make up the extracellular matrix, i.e., the supporting structures that surround the cells. “But at that time, it was thought that there was no extracellular matrix in the brain. After all, the brain is soft and does not need to be supported, as it floats in cerebrospinal fluid under the robust skull.”

However, it gradually became clear that the nerve cells in the brain are also surrounded by a network of extracellular matrix. The matrix actually accounts for up to 25 percent of the brain's volume. The nerve cells themselves, but especially the glial cells, produce the three-dimensional network of proteoglycans. This ensures that messenger substances such as glutamate, which are released at a synapse, do not diffuse too far away but act locally. “The matrix collects ions and messenger substances on site and releases them again directly,” explains Seidenbecher. The extracellular matrix thus has an important buffering and storage function.

Recommended articles

When the matrix disappears, there is room for new learning material

In her experiments on brain sections from mice, Seidenbecher can also artificially break down the matrix of proteoglycans by adding enzymes such as hyaluronidase or chondroitinase. These enzymes split off the sugars, releasing the proteoglycans from the network. Surprisingly, removing the matrix around the nerve cells has a significant effect on the synapses and thus on learning – they become more plastic and strengthen.

This is exactly what happens when we learn something new: the matrix around a synapse, including the prominent molecule brevican, is broken down to allow the synapse to expand. This process is initiated by an external stimulus: and once again, it is the NMDA receptor that triggers the release of matrix-degrading enzymes. “The receptor is the chef and the matrix is the waiter,” Seidenbecher illustrates.

Who would have thought it: part of the secret of how we learn lies not within, but actually outside the nerve cells. When space is created there by loosening the extracellular matrix, we can learn new things more easily. Synapses sprout or expand.

Seidenbecher's colleagues were able to demonstrate the relevance of the matrix particularly impressively in desert gerbils. These rodents have extremely good hearing. The researchers were able to teach them to jump over a hurdle as soon as they heard a whistle with a rising pitch. When they heard a descending whistle, however, they were supposed to remain seated. “They learned this very quickly,” reports Seidenbecher.

However, when the researchers reversed the rule and expected the trained mice to jump when they heard a descending tone, the animals struggled. But after injecting a small amount of a matrix-degrading enzyme into the mice's auditory cortex, the rodents were able to relearn quickly. “Without forgetting the old rule,” reports Seidenbecher.

“In the brain, there is an interplay between stability – meaning that I don't forget who I am – and flexibility – meaning that I can learn new things,” says the researcher. This interplay is largely organized by the extracellular matrix.

Matrix celebrity Brevican predicts brain age

With increasing age, however, the matrix becomes less soluble and less flexible. Some components, such as the proteoglycan brevican, decrease. Astrocytes produce less and less of it and instead release cytokines that summon the immune system and initiate a latent inflammatory process. This is unfavorable – and a characteristic of aging. It is also bad news for mental abilities.

Seidenbecher has already proven that the more brevican people have in their blood, the better they perform on memory and thinking tasks. The molecule outside the nerve cells is now considered a hot candidate for predicting the actual, function-related age of the brain in relation to biological age. Among nearly 3,000 proteins analyzed in the blood, it is one of the substances most closely associated with dementia, strokes, and mobility. More brevican means greater mental fitness.

“Sometimes I am asked if I would inject enzymes into my own brain to break down the extracellular matrix in order to learn new things faster,” says Seidenbecher. “For heaven's sake,” she replies. “That's a sledgehammer approach, and no one knows what the gerbils have lost at the expense of faster relearning.”

The neurochemist prefers to stick to her other research findings. In addition to genes, the level of brevican is significantly influenced by lifestyle: not smoking, not being overweight, and not having too much body fat are good for the protective substance in the brain.