The Secret of Neural Reserve

From the hippocampus to the synapse: A research consortium is investigating which factors protect our thinking in old age – and why superagers often cheat memory loss.

Scientific support: Prof. Dr. Andreas Draguhn

Published: 01.02.2026

Difficulty: easy

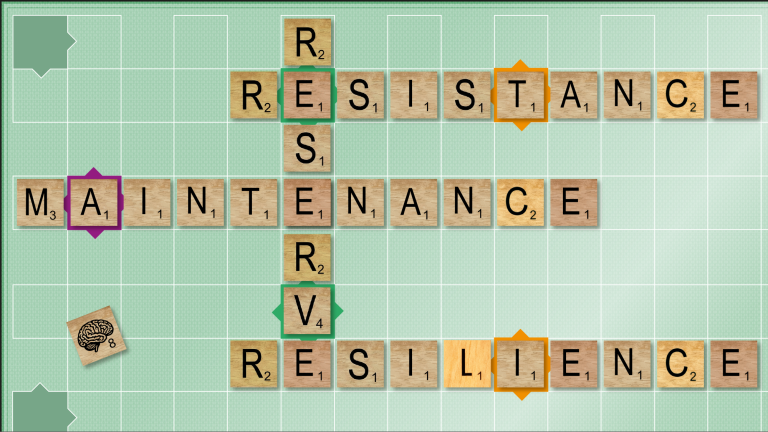

- People age mentally in very different ways – partly due to genetics, partly due to their lifestyle. Collaborative Research Center 1436 is investigating the neural resources behind this and how they can be strengthened.

- The strength of the connections between brain areas is very important for cognitive resources.

- The vulnerability of the so-called grid cell system may explain why some people retain episodic memory and orientation in old age, while Alzheimer's patients lose them early on.

- The visual cortex processes the features of an object sequentially rather than in parallel. This form of visual attention appears to be comparatively robust in old age.

- At the smallest level, synaptic density plays a crucial role. New imaging techniques show early synaptic loss in Alzheimer's disease, while a high synaptic reserve could provide protection.

- Compensation by the cognitive control network: Experiments with sleep deprivation show how the brain can compensate for malfunctions despite reduced resources. This provides clues to compensation mechanisms in old age.

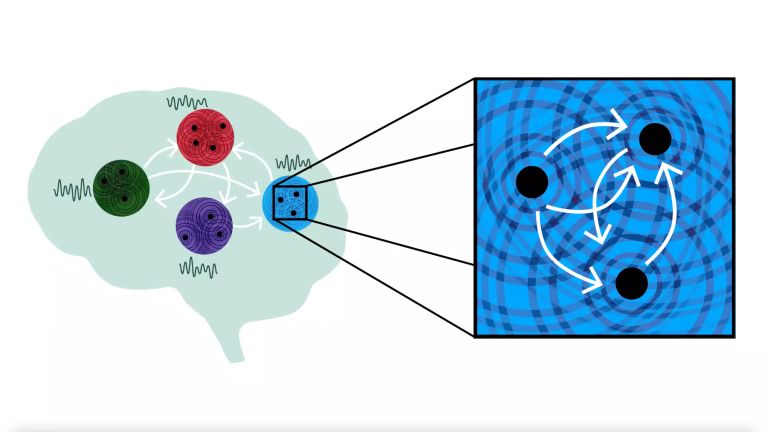

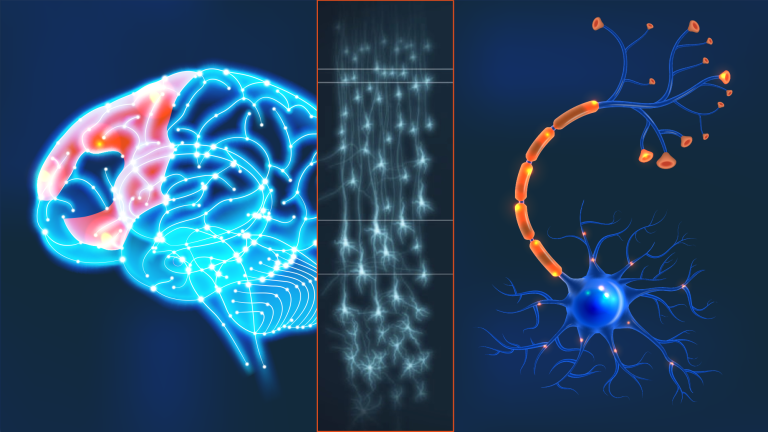

- Macro level: Examination of the brain on a scale of several millimeters and centimeters, analyzing connections between more distant areas.

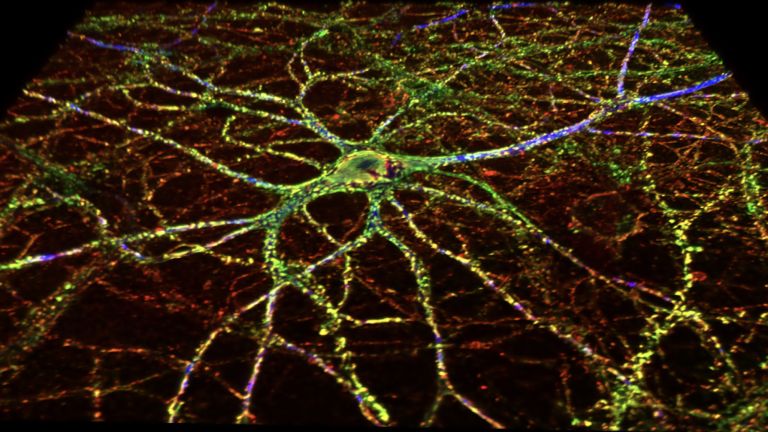

- Meso level: Examination of the brain on a scale of micrometers to several millimeters. Focus: local networks, columns, and cell layers of the cortex.

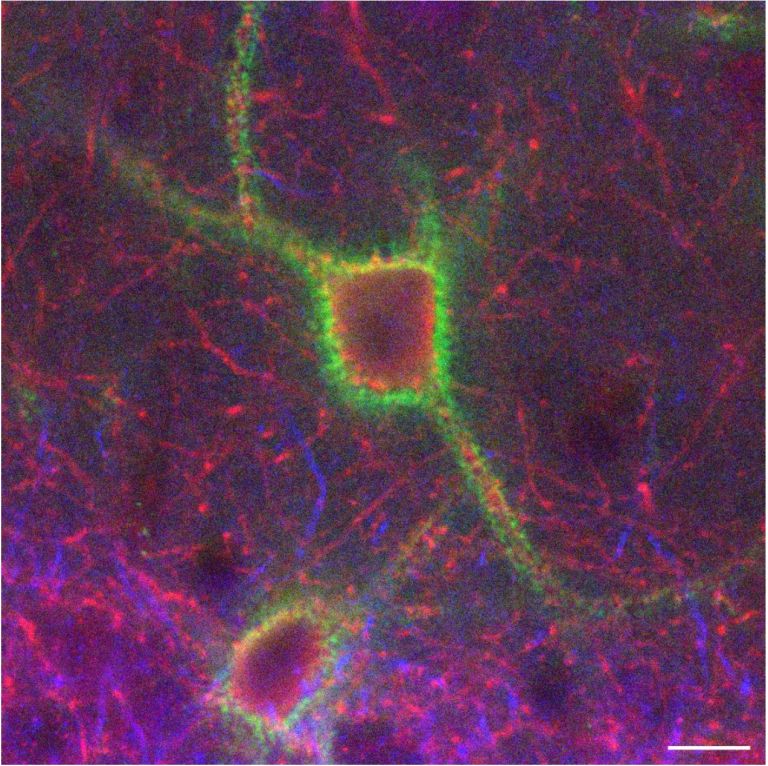

- Micro level: Examination of the brain with a resolution in the nanometer to micrometer range. The focus is on structures such as nerve cells and synapses.

Life isn't necessarily fair, as becomes apparent right from the start. Some people are born with impressive gifts, while others are less blessed. And even towards the end of life, biology deals different hands. Although everyone can influence the aging process to a certain extent through physical and mental activity, genetics also play a significant role in aging. But the genetic lottery plays a major role in aging. As a result, some people in their 80s and 90s still find it easy to concentrate, remember things, or make complex decisions – while others experience mental decline much earlier. This inequality is precisely where Collaborative Research Center 1436 comes in. Its goal: to find out what neural resources our brain possesses, why they remain stable in some people – and how they can be trained.

“In our research, we look at how cognitive resources – specifically, memory performance – change in the course of aging,” says anatomist and neuroscientist Anne Albrecht from the University of Magdeburg. The researchers are examining this at various levels. At the so-called macro level, they are studying the brain on a scale of several millimeters to centimeters. Methods such as functional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are used for this purpose. “At the macro level, the focus is on how different areas of the brain interact with each other,” says Albrecht. The hippocampus plays a central role in memory. “It is connected to numerous other areas of the brain, such as the neocortex,” explains the neuroscientist. “Memories are stored long-term in its networks.” She emphasizes that the strength of the connection between areas of the brain is very important for cognitive resources. Sometimes, new interactions even arise between areas that previously had little communication with each other – a potential protective factor against mental decline.

Zooming further into the brain takes us to the so-called meso level, with a resolution ranging from micrometers to a few millimeters. “Here we look at local and neighboring circuits, such as connections within the cerebral cortex or specific inputs,” explains Anne Albrecht. For example, the entorhinal cortex provides the hippocampus with important information via synaptic connections. Especially when we remember an emotionally significant event, the brain stores information from the various sensory organs. What did the room look like where I met my friends? What background noises could be heard? “The entorhinal cortex collects this various information, links it, and pre-processes it,” says Albrecht. “The hippocampus then decides what goes into the memory trace.”

Neural navigation system

The entorhinal cortex also contains so-called grid cells (Link Mosers). These are specialized cells that create a kind of internal coordinate system. They fire in a regular pattern when moving, which can be superimposed on space like a grid. This makes them a neural navigation system that helps us orient ourselves spatially.

“For this reason alone, grid cells are an important neural resource,” says psychologist and neuroscientist Thomas Wolbers from DZNE Magdeburg. However, it is a resource that Alzheimer's patients lose early on in the course of the disease. But Wolbers is interested in something else: the grid cell system could also be important for episodic memory – that is, for what happened, when, and where. Episodic memory also ceases to function in people with advanced Alzheimer's disease.

However, even in people who are aging normally, changes in the grid cell system become apparent over the years. Wolbers and his colleagues are therefore pursuing a hypothesis: Could the varying susceptibility of the grid cell system be decisive in determining whether a person's episodic memory and spatial orientation are preserved or decline? To test this, they are comparing Alzheimer's patients, normally aging individuals, and so-called superagers – people over the age of 80 whose memory performance is similar to that of people who are a good 30 years younger. “We suspect that in superagers, the grid cell system is still intact as a neural resource,” says Thomas Wolbers. Studies of deceased brains show, for example, that the entorhinal cortex in superagers has structural features – in some cases, the neurons are larger.

But not every cognitive resource is so vulnerable. “In the visual cortex, there are specialized nerve cells that fire more intensely when subjects see a certain color on an object, for example,” says neuroscientist Jens-Max Hopf from the University of Magdeburg. For a long time, it was unclear how the brain processes different colors of an object seemingly simultaneously. Experiments conducted by Hopf's research group show that the visual cortex is probably not a true multitasker. Rather, it processes sensory impressions one after the other: if subjects turn their attention to two groups of dots that change color, the visual cortex first processes one group and then, about 500 milliseconds later, the other. Initial data suggest that this mechanism of visual perception remains relatively stable in old age. “Degradation processes in the visual cortex appear to play a lesser role – a potentially robust cognitive resource.”

Recommended articles

It's all about density

Zooming in even deeper on the brain takes us to the micro level. This involves structures in the micrometer range and below, neurons and synapses. Researchers examine these using electron microscopes, for example. “Synaptic connections are important for cognitive resources,” says Anne Albrecht. When we learn something, neurons begin to communicate with each other in an optimized way. This happens via the synaptic connections. “In old age, memory function may no longer work as well,” says Albrecht. This could be because new connections can no longer be formed properly, existing connections are destroyed, or the basis for a connection is missing because neurons have been lost in the course of neurodegeneration. One cognitive resource, on the other hand, could be to create more synaptic connections at a younger age through training, for example by learning several languages, learning a musical instrument, or pursuing higher education. “With a larger base of connections, memory loss would not occur as quickly in the course of aging.”

Henryk Barthel, a nuclear medicine specialist at Leipzig University Hospital and Dessau Municipal Hospital, is investigating whether higher synaptic density protects against mental decline. Only recently has it become possible to image synaptic density in living humans using positron emission tomography (PET). According to Barthel, there are initial indications that, particularly in Alzheimer's disease, synapse density is reduced in certain regions of the brain, such as the hippocampus. And this can possibly be observed relatively early in the course of the disease. “One hope is that imaging synapse density will improve early diagnosis.” Barthel and his colleagues are looking at the other end of the spectrum, namely superagers. The researchers' hypothesis is that superagers have better brain reserve and therefore respond better to aging processes. “It is possible that this brain reserve consists of a higher density of synapses,” says Barthels.

And it is possible that not only the number but also the type of synapses plays a role here. This is because, in addition to excitatory neurons, which simply pass on information, there are also inhibitory neurons. “They influence whether and how information is passed on,” says Anne Abrecht. And some help “... to suppress irrelevant information about the environment, the context, when specific information is available at the same time.” Concentration is therefore always a matter of functioning neural inhibition.

Made “old” by sleep deprivation

Not everyone is lucky enough to be a superager. But even declining resources can apparently be compensated for to a certain extent. Neuropsychologist Markus Ullsperger is examining this effect. To replicate what happens in the aging brain, he keeps young, healthy adults awake. Sleep deprivation serves as a model for how neural resources decline with age. This allows researchers to study how the brain copes with this.

“As a result of sleep deprivation, local parts of brain regions are put into a sleep-like state for a few hundred milliseconds while processing tasks,” says Ullsperger. This can affect the occipital and parietal cortex, for example. “Brain regions like these can be prevented from performing their normal tasks during this time.” This limits resources such as perception and attention, causing those affected to make more mistakes. Here the so-called cognitive control network in the brain comes into play, monitoring actions and watching out for mistakes. It is based on the interaction between prefrontal and parietal areas, as well as the basal ganglia. “This network can pool the neural resources that a person currently has.” This makes it possible, for example, to improve attention to a task and thus also performance. Ullsperger and his colleagues hope to use the cognitive control network to improve mental performance when resources are limited.

The brain is probably the most complex organ we have. It may also be the most important, because our entire mental abilities depend on it. With its findings, superager research may pave the way for making life a little fairer from a neurobiological perspective – so that more people can age well mentally.