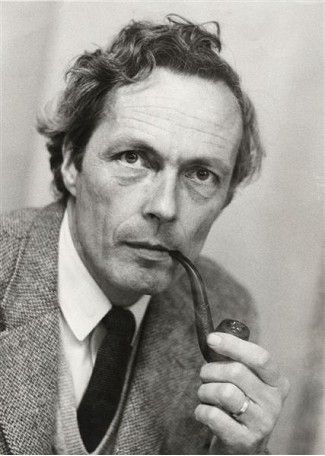

Otto Creutzfeldt: Mediator between Disciplines

Otto Detlev Creutzfeldt was a pioneer in neurophysiology. However, he not only contributed to our understanding of the brain through his experiments, but also shaped an entire generation of neuroscientists as a doctoral supervisor and mentor.

Wissenschaftliche Betreuung: Prof. Dr. Heinz Wässle

Veröffentlicht: 28.09.2012

Niveau: mittel

- Der Neurophysiologe Otto Detlev Creutzfeldt lieferte grundlegende Arbeiten zum Krankheitsbild der Epilepsie und zum Verständnis der Hirnrinde beim Sehen und Sprechen.

- In den 60er Jahren arbeitete er an der intrazellulären Ableitung von cortikalen Neuronen. Zusammen mit Kollegen half er, die neurophysiologischen Grundlagen des EEGs zu verstehen.

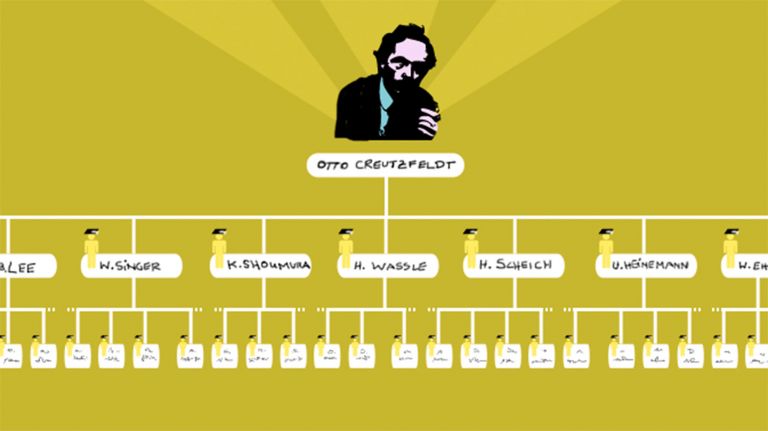

- Creutzfeldt prägte als Lehrer und Mentor viele Neurowissenschaftler. Zu seinen Schülern gehört der Nobelpreisträger Bert Sakmann sowie die Forscher Heinz Wässle, Henning Scheich und Wolf Singer.

1. April 1927: Otto Detlev Creutzfeldt wird in Berlin geboren

1945: Studium der Geschichte, Philosophie und Theologie in Tübingen

1948: Studium der Medizin

1953: Promotion in Freiburg, Thema: Experimentelle Epilepsie des Ammonhornes

1960/61: Forschungsaufenthalt an der University of California in Los Angeles

1963: Habilitation in der klinischen Neurophysiologie am Max-Plack-Institut für Psychiatrie in München

1965: Wissenschaftliches Mitglied der Max-Planck-Gesellschaft

1968: Direktor der Abteilung Neurobiologie am Max-Plack-Institut in Göttingen

23. Januar 1992: Creutzfeldt stirbt

Some scientists make a name for themselves in their discipline through outstanding research. Only a few succeed in inspiring an entire generation of researchers beyond that. Neurophysiologist Otto Creutzfeldt is one of them. “Hardly any other scientist has influenced me as much as Creutzfeldt, who inspired me to pursue a career in neuroscience,” said Nobel Prize winner Bert Sakmann. He studied under Creutzfeldt as a doctoral student. The two continued to work together later on. It was in Creutzfeldt's department that Sakmann conducted his outstanding research on ion channels in cell membranes. For this, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 1991, together with Erwin Neher.

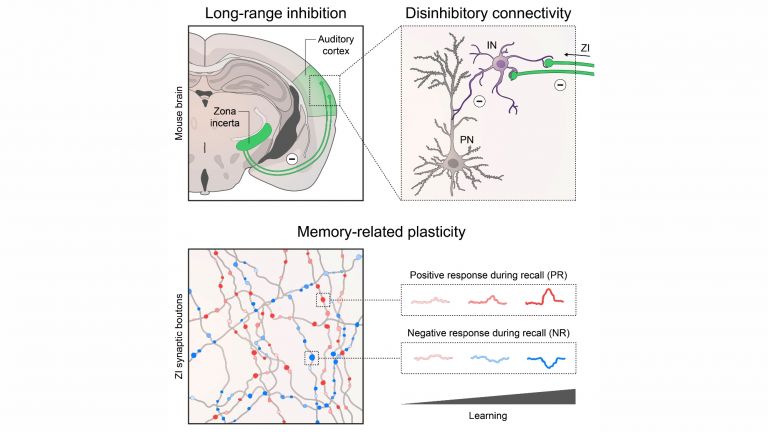

Numerous other doctoral students of Creutzfeldt continue to shape neuroscience in Germany today, having become professors at universities and Max Planck and Leibniz institutes. Henning Scheich, for example, was one of the most renowned experts on the subject of learning. Heinz Wässle is a world-renowned neuroanatomist. And brain researcher Wolf Singer has become known to the public not only for his theories on free will. Creutzfeldt not only taught them all the basics of neurophysiology, but he also passed on his enthusiasm and fascination for brain research.

When they hear the name Creutzfeldt, many people first think of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. This is a rare neurodegenerative disorder that is associated with BSE (Bovine spongiforme Enzephalopathie) in cows. However, it was Otto Creutzfeldt's father, Hans-Gerhard, who discovered the disease: he was a neurologist and in 1913 found unusual changes in the brain of a patient with a then unknown disease. In 1922, Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease was named after him and his colleague Alfons Maria Jakob, and the family name became inextricably linked with neuroscience. So, his son Otto grew up in an environment that dealt with nerves and diseases.

The humanist

However, after graduating from high school, he initially pursued a different path, beginning studies in theology, history, and philosophy at the universities of Kiel and Tübingen in 1945. Philosophical topics fascinated him throughout his life and may even have been the source of his scientific motivation. Wolf Singer later described him as a “true humanist.” He wanted to understand the mysteries of life and the nature of human beings.

The humanities alone were not enough for him. After three years, he dropped out of his studies and turned to his father's field of research, studying medicine and neurophysiology. Creutzfeldt received his doctorate in Freiburg in 1953, researching a brain structure called Ammon’s horn. Damage to this part of the cerebrum often triggers epileptic seizures. Until 1959, he worked as a research assistant to Richard Jung, the famous Freiburg neurologist;his period shaped Creutzfeldt like no other. His doctoral supervisor was working at the time on measuring electrical activity in the mammalian brain. The connection between brain waves and behavior, sensory impressions, and diseases fascinated him.

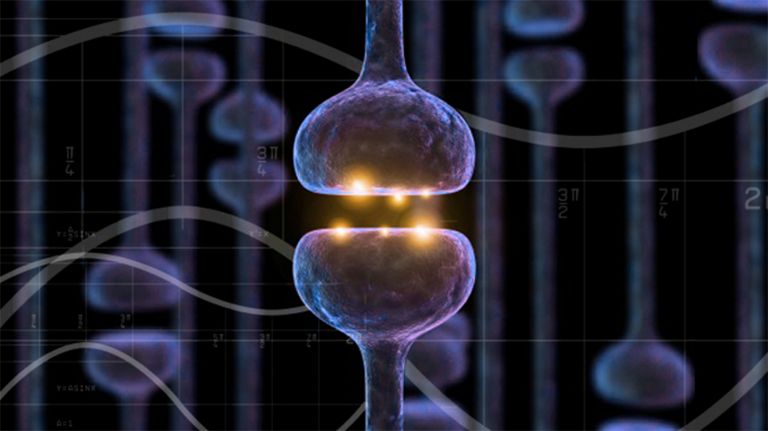

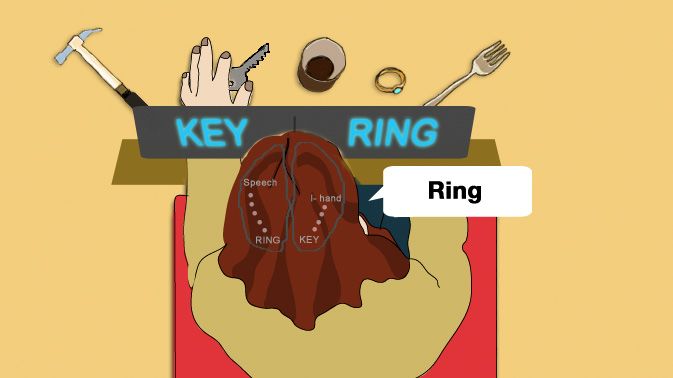

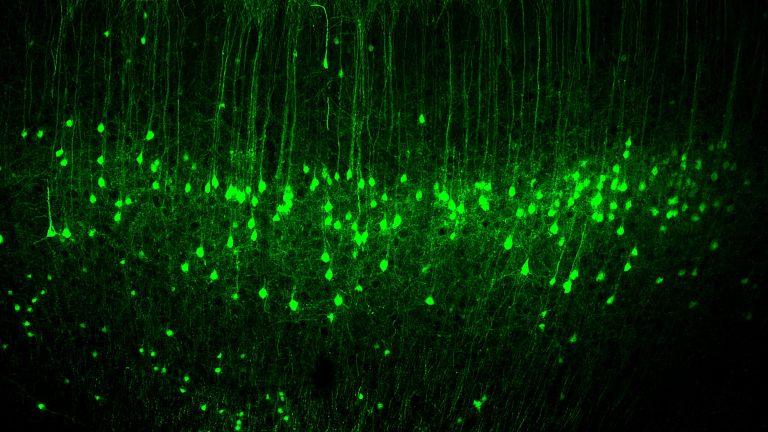

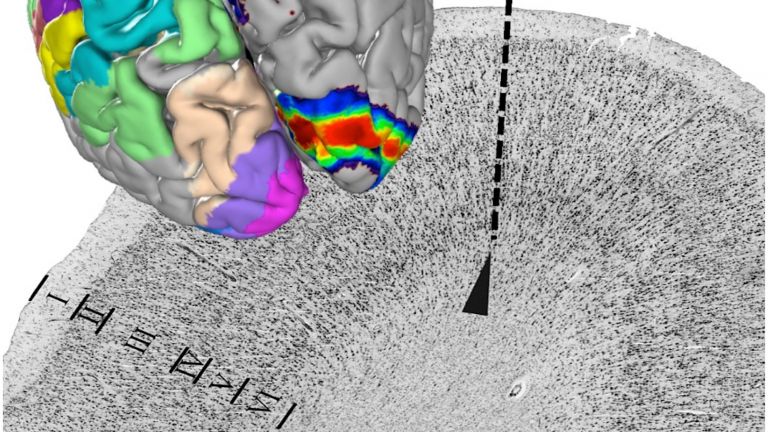

Creutzfeldt published fundamental work on the sleep-wake cycle, the sense of sight, and language. Like Jung, he also attempted to measure the electrical currents of individual cells – a challenging and difficult technique at the time. This required inserting a microelectrode into the brain without damaging it. When the tip of the electrode came close to a neuron, its electrical activity could be measured. Creutzfeldt began to use the method to study one of the most complex structures of the brain: the cerebral cortex. He understood that it would remain one of the greatest challenges of his scientific career. He continued to study the sense of sight and the associated structures in the cortex until the end of his life. He later compiled his knowledge of the structure and function of the cerebral cortex in his textbook Cortex Cerebri, which is essential reading for many neuroscientists.

Cortex

Großhirnrinde/Cortex cerebri/cerebral cortex

Cortex bezeichnet eine Ansammlung von Neuronen, typischerweise in Form einer dünnen Oberfläche. Meist ist allerdings der Cortex cerebri gemeint, die äußerste Schicht des Großhirns. Sie ist 2,5 mm bis 5 mm dick und reich an Nervenzellen. Die Großhirnrinde ist stark gefaltet, vergleichbar einem Taschentuch in einem Becher. So entstehen zahlreiche Windungen (Gyri), Spalten (Fissurae) und Furchen (Sulci). Ausgefaltet beträgt die Oberfläche des Cortex ca 1.800 cm2.

Empfohlene Artikel

Insights into the brain

In his early years of teaching, however, he was not yet so focused, dabbling in everything that interested him: physiology, psychiatry, and neurology. He found a good place for this in Freiburg. The clinic headed by Richard Jung not only researched the causes of mental and neurological disorders, but also treated patients. This greatly helped Creutzfeldt to understand the brain; he did not have to content himself with animal experiments but could also see what happens in humans when something is wrong in the brain.

Creutzfeldt also has the opportunity to work with scientists such as Otto-Joachim Grüsser, Hans Kornhuber, Günther Baumgartner, and Rudolph von Baumgarten, to conduct research, to formulate theories, to reject them, and to improve them. The clinic attracts young neurologists whose scientific careers are shaped here. And these colleagues become friends.

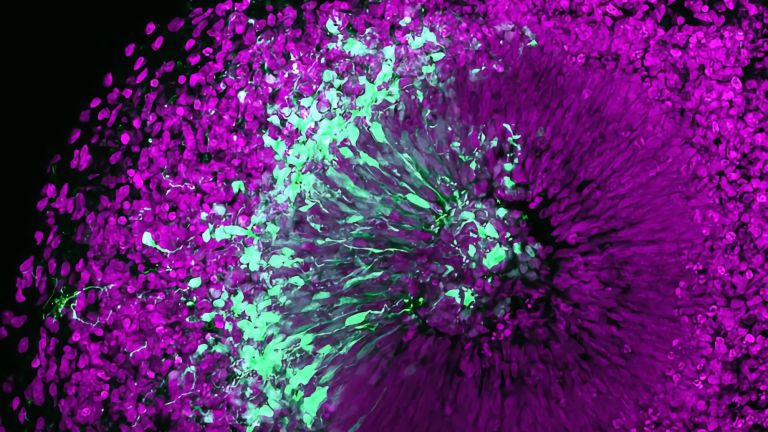

After completing his doctorate and a research stay in Los Angeles, Creutzfeldt moved to Munich to conduct research at the Max Planck Institute of Psychiatry and qualify as a professor in clinical neurophysiology. Once again, it was brain waves that preoccupied him. Here, he succeeded in measuring voltage changes within individual nerve cells of the cortex. This helped him understand how messages are processed in higher brain centers and also gave him insights into the structure of the brain. He also succeeded in clarifying a fundamental question. Scientists and physicians had long been able to measure currents using electrodes on the scalp, but how the signals on the electroencephalograph (EEG) were generated was not fully understood. In the 1960s, Creutzfeldt, together with Manfred Klee and Hans Dieter Lux, succeeded in clarifying the origin of brain waves. They anesthetized cats and measured the currents in neurons of the cortex. They discovered that the EEG signal is the sum of the activities of many individual nerve cells in the cerebral cortex.

Creutzfeldt's students

But Creutzfeldt did not stay in Munich for long. In 1968, biophysicist Manfred Eigen, director of the Department of Neurobiology, recruited him to the newly founded Max Planck Institute for Biophysical Chemistry in Göttingen – his last scientific post.

There, he found himself in the same situation as many scientists who take on management roles: he had to do a lot of paperwork and was often tied to his office. Nevertheless, he insisted on returning to the laboratory to conduct experiments. Scientific research and the joy of experimentation remained an important part of his life. No sooner had he found answers in one field than new questions arose, and not only in science. He also pondered the ethical consequences of his work, being particularly interested in philosophical ideas about consciousness. He repeatedly asked himself how the mind is connected to nerve cells. Thinking was linked to the brain, but did that explain it? Through numerous speeches, essays, and papers, Creutzfeldt attempts to connect what is close to his heart: neuroscience and the humanities.

Meanwhile, in the laboratory, he trained young scientists who would go on to make scientific history a few years later. Alongside Nobel Prize winner Bert Sakmann, one such scientist was Wolf Singer: he was so fascinated by a seminar given by Creutzfeldt at the Max Planck Institute of Psychiatry that he wrote his doctoral thesis in this field. Today, Singer is director emeritus at the Max Planck Institute for Brain Research in Frankfurt while continuing his work at the Ernst Strüngmann Institute, which he founded as well. And for many years Singer himself had a formative influence on the next generation of researchers.

On January 23, 1992, Creutzfeldt died a few months before his 65th birthday. In the same year, Creutzfeldt was posthumously awarded the Zülch Prize for his work in the field of neurophysiology of vision and language. When the Otto Creutzfeldt Center for Cognitive and Behavioral Neuroscience (OCC) opened at the University of Münster in 2006, Creutzfeldt's wife, Mary, was also present. Once again, she recalled her husband's enthusiasm: “He always equated work with fun.”

Further reading

- Reichardt, W. und V. Henn: In memoriam, Otto D. Creutzfeldt 1927 – 1992; Biological Cybernetics. 1992; 67:386 – 386.