Alois Alzheimer: Mad-Doctor with a Microscope

He was so fascinated by the mysterious symptoms of one patient that he did everything he could to examine her. It took not only his perseverance, but also numerous strokes of luck for Alois Alzheimer to become famous.

Wissenschaftliche Betreuung: Dr. Oliver H. Peters

Veröffentlicht: 18.09.2013

Niveau: leicht

- Alois Alzheimer begegnet Auguste Deter im Jahr 1901. Sie zeigt für eine 51-Jährige eine ungewöhnliche Verwirrtheit. Sie kann sich an fast nichts erinnern.

- Selbst als Alois Alzheimer an eine andere Klinik wechselt, lässt er sich über den Krankheitsverlauf von Auguste Deter informieren.

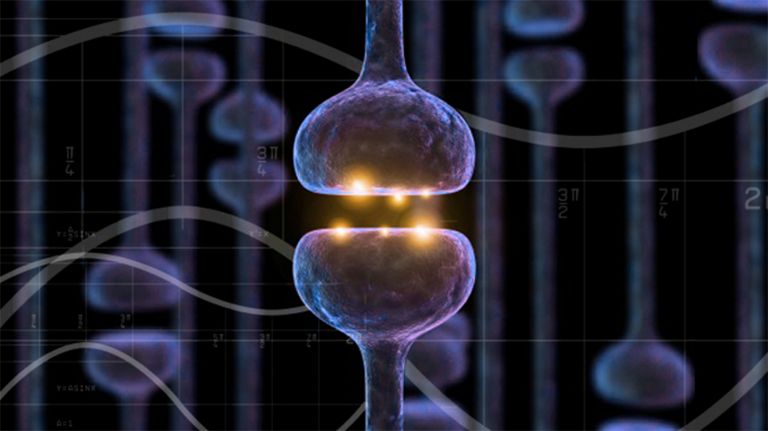

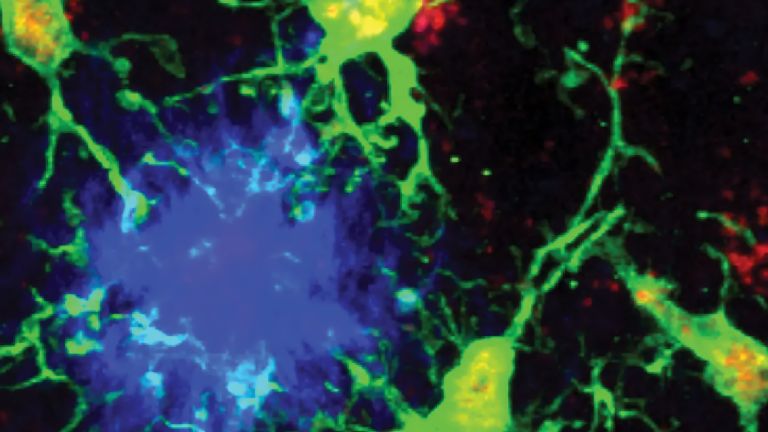

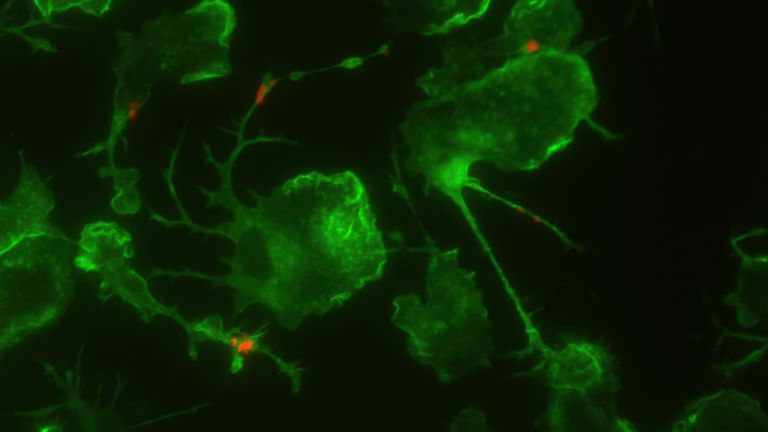

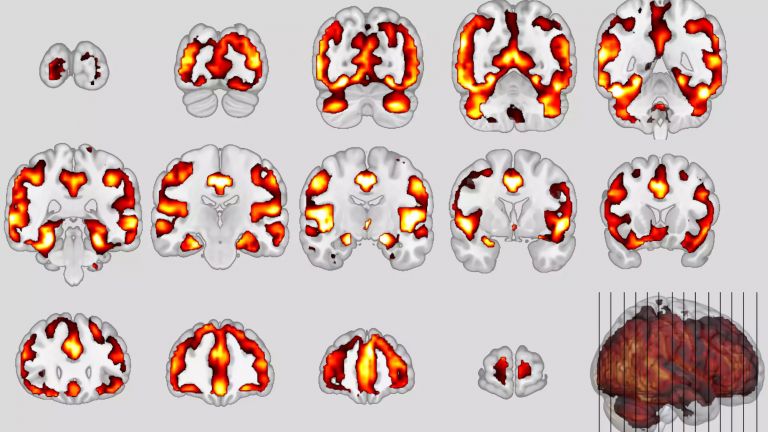

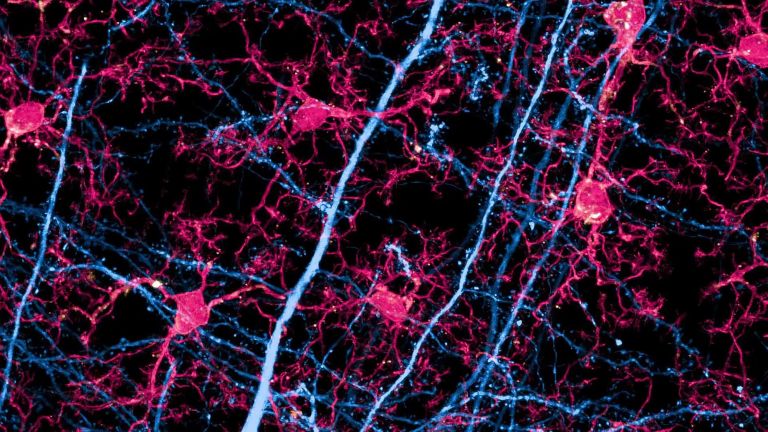

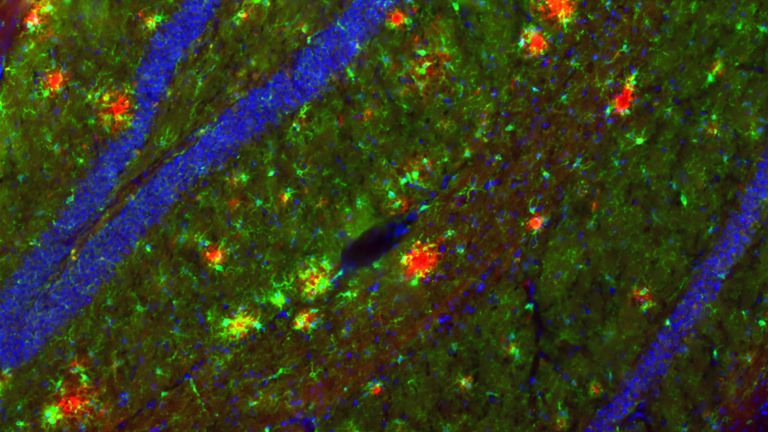

- Nach dem Tod von Auguste Deter findet Alois Alzheimer auffällige Hirnveränderungen: Der Cortex ist geschrumpft, unter dem Mikroskop sieht er ungewöhnliche Fibrillen und Plaques.

- Als Alois Alzheimer sein Erkenntnisse über Auguste Deter bei einem Kongress vorträgt, reagiert die Wissenschaftswelt mit Desinteresse.

- Sein Name wird mit dieser Krankheit erstmals in einem Lehrbuch seines Chefs Emil Kraepelin verknüpft: „Alzheimers Krankheit“.

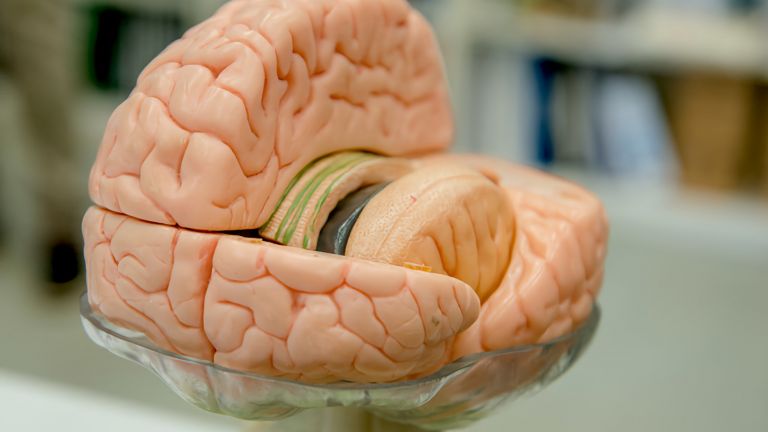

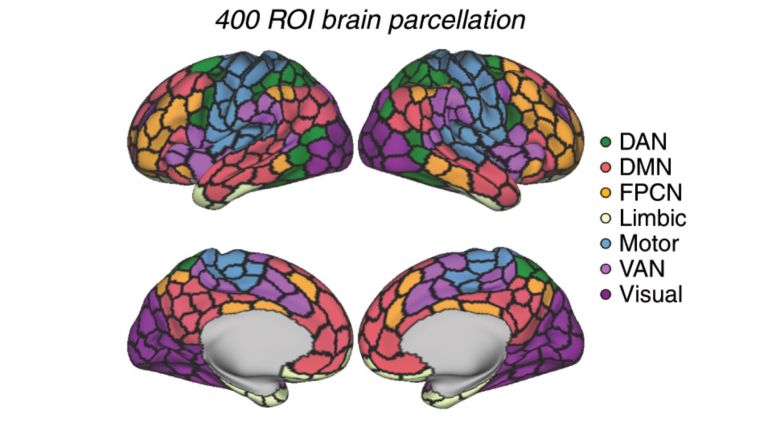

Cortex

Großhirnrinde/Cortex cerebri/cerebral cortex

Cortex bezeichnet eine Ansammlung von Neuronen, typischerweise in Form einer dünnen Oberfläche. Meist ist allerdings der Cortex cerebri gemeint, die äußerste Schicht des Großhirns. Sie ist 2,5 mm bis 5 mm dick und reich an Nervenzellen. Die Großhirnrinde ist stark gefaltet, vergleichbar einem Taschentuch in einem Becher. So entstehen zahlreiche Windungen (Gyri), Spalten (Fissurae) und Furchen (Sulci). Ausgefaltet beträgt die Oberfläche des Cortex ca 1.800 cm2.

14. Juni 1864 Alois Alzheimer kommt in Martkbreit in Unterfranken zur Welt

1884 – 1888 Medizin-Studium inklusive Promotion in Berlin, Würzburg und Tübingen

1888 – 1902 Arbeit als Arzt an der „Anstalt für Irre und Epileptische“ in Frankfurt am Main

1895 Heirat mit der Witwe Cecile Geisenheimer, die ihm drei Kinder gebiert

1901 Tod von Cecile Alzheimer

1901 Erste Begegnung mit der Patientin Auguste Deter

1902 – 1912 Arbeit unter Emil Kraepelin, zunächst in Heidelberg, ab 1903 an der Psychiatrischen Klinik München

1906 Vortrag vor der „Versammlung südwestdeutscher Irrenärzte“ in Tübingen, in dem Alois Alzheimer erstmals die später nach ihm benannte Krankheit beschreibt

1912 Übernahme einer Professur an der Universität in Breslau

19.12.1915 Alois Alzheimer stirbt an Nierenversagen

At first, Alois Alzheimer only knows Auguste Deter from her medical records. She is only 51 years old, but she shows a level of confusion that is more commonly expected in very old people. Her husband has admitted her to the Institution for the Insane and Epileptics in Frankfurt am Main. At that time, in 1901, Alzheimer is a senior physician there, and his assistant physician, Fritsche, has conducted the patient's initial examination. What he wrote about it aroused Alzheimer's curiosity, and he paid Deter a visit. He documented his first conversation in detail:

“What is your name?”

“Auguste.”

“Family name?”

“Auguste.”

“What is your husband's name?”

“I think Auguste.”

“Your husband?”

“Oh, my husband...”

“Are you married?”

“To Auguste.”

The entire conversation continues in this vein: Sometimes Auguste Deter answers normally, but most of the time her answers do not really match the questions. Alzheimer finds this so extraordinary that he immediately decides to pay special attention to the patient. This decision has far-reaching consequences, because it means that today, more than 100 years after this encounter, the name Alzheimer is known worldwide and is inextricably linked to a common form of dementia. But for this fame to come about, it took many coincidences – and the perseverance of Alzheimer, whose research findings were initially ignored by the scientific community.

The first stroke of luck was the aforementioned Frankfurt institution where Alzheimer was working at the time of his encounter with Deter. This institution did not limit itself to locking up the mentally ill, as was still common practice in many places at the time. Instead, it placed great importance on treating patients according to the most modern psychiatric findings of the time. Alcoholics, for example, were given work therapy, while those suffering from delusions were given long baths. Above all, however, the doctors dealt with the patients in depth – otherwise Deter's unusual symptoms would not have been described and examined in such detail.

“Write ‘Mrs. Auguste Deter,’” Alzheimer instructs her on the first day of examination. She writes “Mrs.,” then stops, having already forgotten the rest. When he prompts her with the next word, she first writes ‘Augtr’ and then “Auguse.” It is as if her former knowledge is only returning in small fragments. The piece of paper with the writing attempts is part of the medical file that was long considered lost and was only found in 1995 in the archives of the Frankfurt University Hospital. The quoted dialogue and the now world-famous photo of the first diagnosed Alzheimer's patient, Auguste Deter, also come from this file.

The paths of doctor and patient diverge

“Her entire demeanor bore the stamp of complete helplessness”, Alzheimer later said about her. “When reading, she jumps from one line to the next, reading letter by letter or with meaningless emphasis.” She often has crying fits because she is so angry at her own inability. “I have lost myself, so to speak,” she once said. A year after her admission, her husband has difficulty paying the costs of her stay in the institution, and Deter is to be transferred to another clinic. Alzheimer has now developed such a keen scientific interest that he campaigns vigorously for Deter to remain. He writes certificates and petitions to the authorities and convinces his head – with success, she stays.

Alzheimer, on the other hand, leaves the institution shortly afterwards. He wants to pursue a scientific career and qualify as a professor under a famous psychiatrist: Emil Kraepelin. He conducts research with him, first in Heidelberg, later in Munich. But he cannot let go of the case of Auguste Deter and regularly checks in with his former colleagues in Frankfurt to find out how her illness is progressing. He learns that the patient is getting worse and worse. "Always lies in bed with her legs drawn up; regularly soiled with feces and urine; never speaks. She just hums to herself and has to be fed. Sometimes she becomes agitated for no apparent reason, disturbing others with loud screaming and humming," states an entry in her medical record from July 1905. She died a year later from blood poisoning as a result of bedsores.

Empfohlene Artikel

Auguste Deter's brain is dissected

After her death, the most decisive coincidence for Alzheimer's later fame occurs. He has not been Deter's doctor for four years, but nevertheless manages to persuade his former head in Frankfurt to do something unusual: he has the brain of the patient with the mysterious disease sent to Munich.

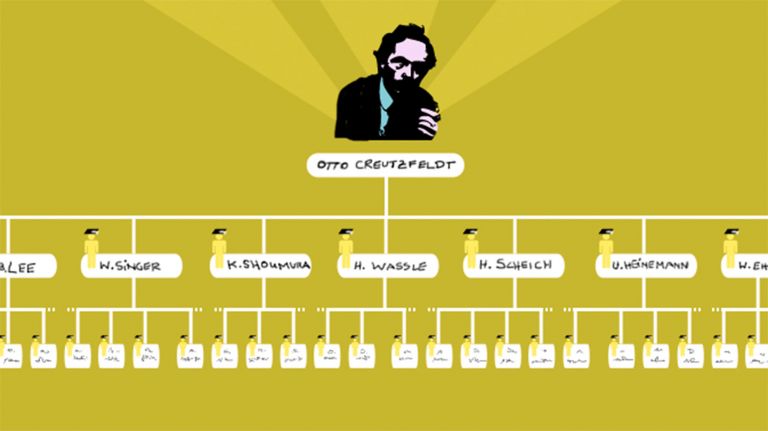

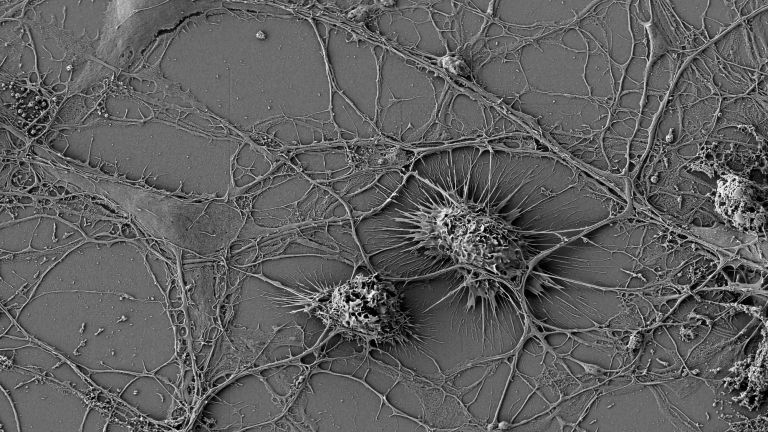

Alzheimer was highly trained in examining the organ – another stroke of luck. During his studies in Würzburg, a luminary had initiated him into the secrets of microscopy: Albert von Kölliker. His students included the future Nobel Prize winner Alfonso Corti, who discovered the organ of Corti, and Franz von Leydig, who discovered Leydig cells. Franz Nissl, inventor of Nissl staining and discoverer of Nissl bodies, became a good friend of Alzheimer. His passion for examining brain sections dates back to this time; he is often referred to as the “mad-doctor with a microscope.” His skill in this field stands him in good stead when analyzing Deter's brain.

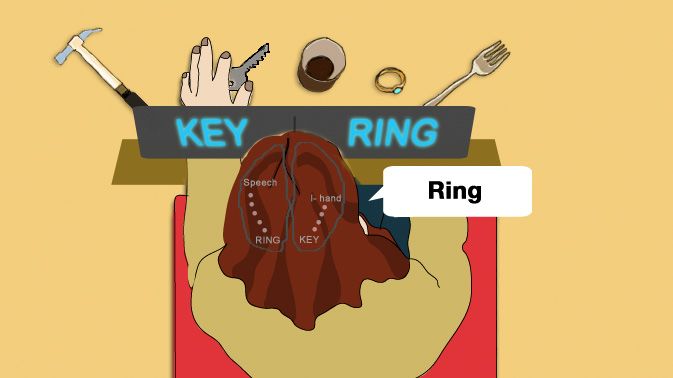

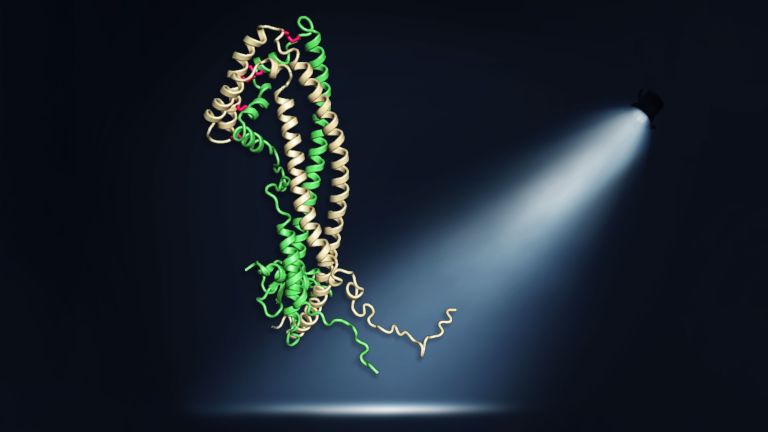

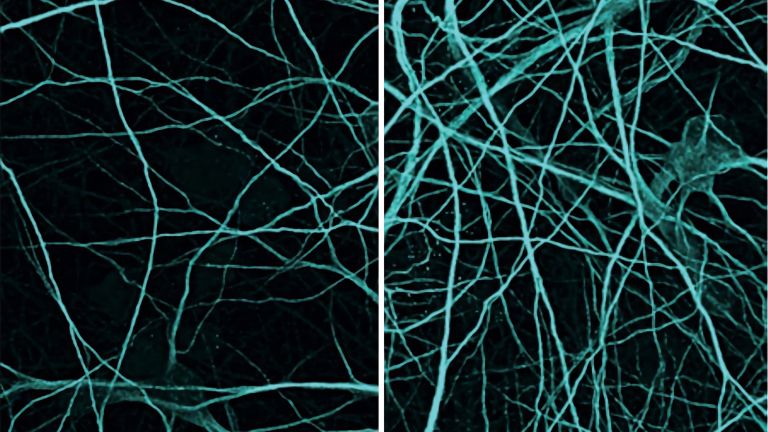

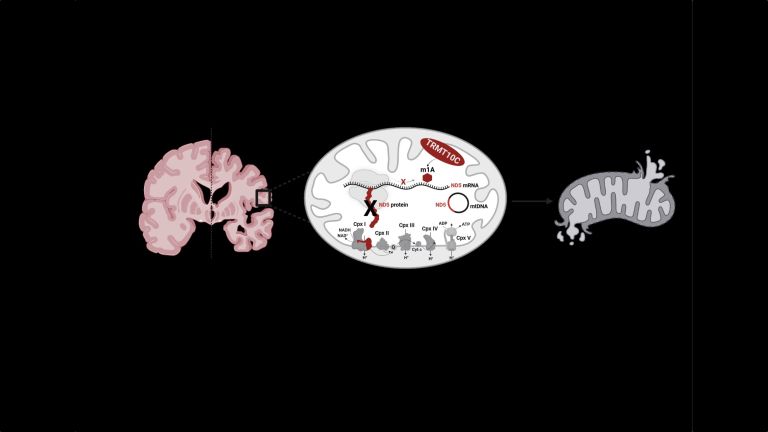

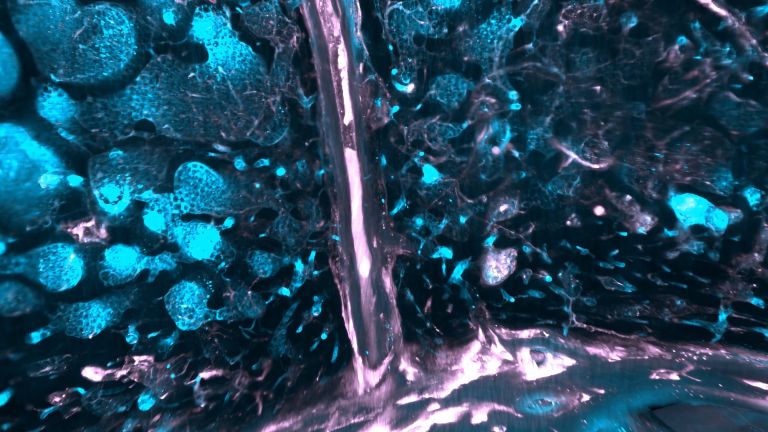

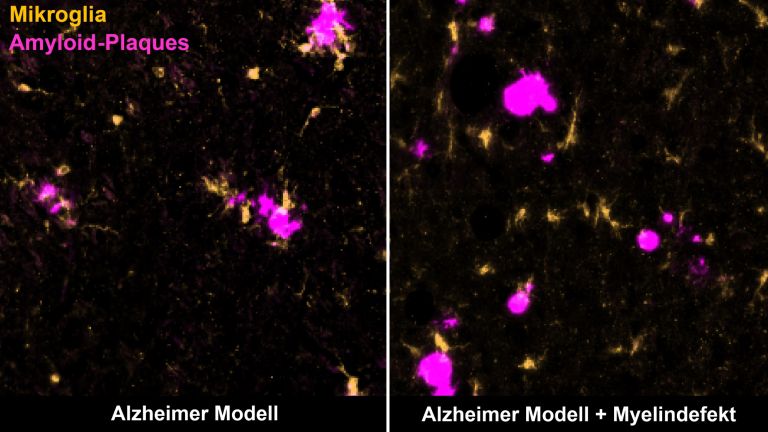

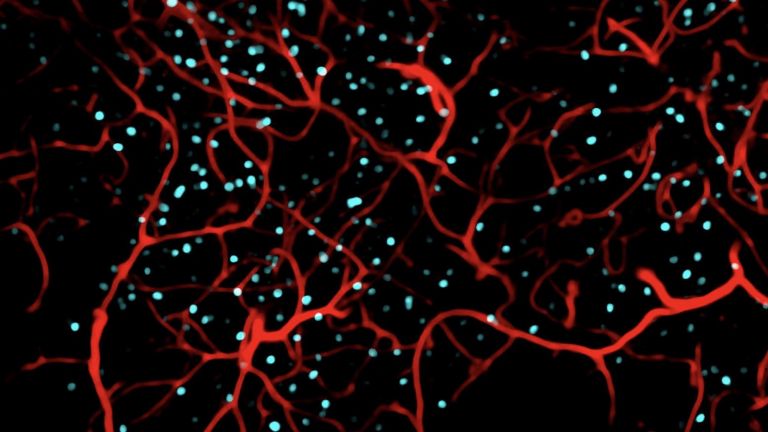

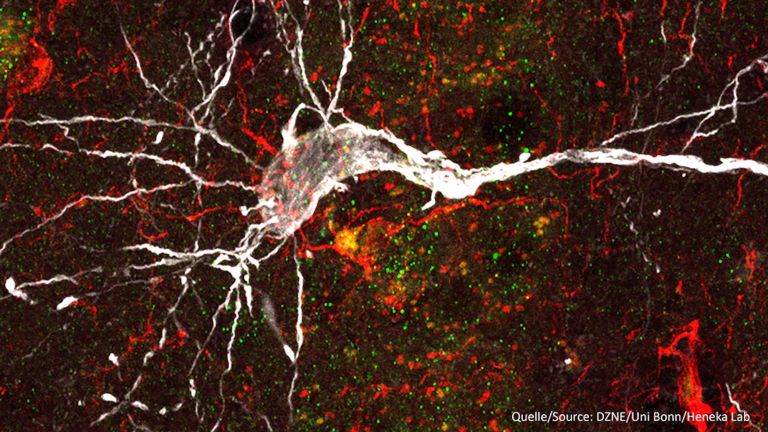

First, he notes that the cerebral cortex has shrunk significantly. Using a microscope, he discovers two further abnormalities: unusual fibrils are visible. He also finds strange lumpy structures, known as plaques, in the cells. Alzheimer speculates that a metabolic product has accumulated there and promoted the disease – a conjecture that proves to be correct decades later.

1906: The Congress in Tübingen

In 1906, Alzheimer proudly presents his findings at the Meeting of Southwest German Psychiatrists in Tübingen. Many important scientists are present, including those who would later give their names to phenomena such as “Bumke's Zeichen” (Oswald Bumke), “Binswanger's disease” (Otto Binswanger), and “Doederlein's bacillus” (Albertz Döderlein). None of them have any idea of the importance of the findings Alzheimer presentsby . None of the researchers present asked any questions – that's how unimportant they found the lecture. It was much more exciting to argue about a new scientific discipline: psychoanalysis. After all, C.G. Jung, a student of Sigmund Freud, was present. Diseases that cannot be traced back to childhood experiences but – as in the case of Auguste Deter – have physiological causes in the brain are of no interest. The minutes of the event describe Alois Alzheimer's lecture, which was later so often quoted, as “not suitable for a presentation.” It only appeared in a specialist magazine a year later.

The fact that the disease was named after him despite this ignorance on the part of the scientific world is thanks to another stroke of luck: Emil Kraepelin, his chief at the clinic in Munich, is the author of the seminal work Psychiatrie: ein Lehrbuch für Studierende und Ärzte (Psychiatry: A Textbook for Students and Doctors). The 8th edition is about to be revised, and in it he mentions his colleague in the chapter “Senile and Presenile Insanity”: “Alzheimer described a peculiar group of cases with very severe cellular changes.” The table of contents contains the first mention of the name of the disease that would later become so famous: “Alzheimer's disease.”

Further reading

- Maurer, K et al: Auguste D and Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet 1997 (349)1546 – 49 (to the text).