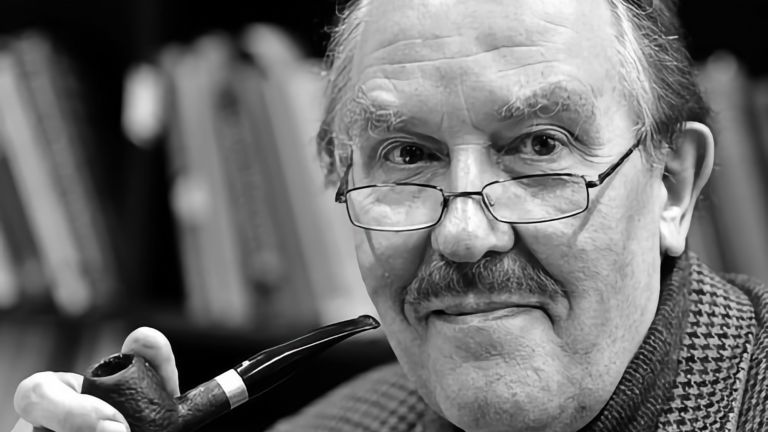

Konrad Lorenz: Behavioral scientist and father of geese

Konrad Lorenz is considered one of the co-founders of behavioral research. He received the Nobel Prize for his research. He supported Nazi ideology.

Wissenschaftliche Betreuung: Prof. Dr. Ute Deichmann

Veröffentlicht: 21.08.2014

Niveau: mittel

- Der Österreicher Konrad Lorenz gilt als „Gänsevater“ und Mitbegründer der Vergleichenden Verhaltensforschung, der so genannten Ethologie.

- 1973 bekommt Konrad Lorenz zusammen mit Karl von Frisch und Nikolaas Tinbergen den Nobelpreis für Physiologie oder Medizin „für ihre Entdeckungen betreffend den Aufbau und die Auslösung von individuellen und sozialen Verhaltensmustern“.

- Konrad Lorenz hat diverse Schriften mit nationalsozialistischer Terminologie verfasst und hatte beantragt, in die NSDAP aufgenommen zu werden. Ob er wirklich der nationalsozialistischen Ideologie anhing oder ob er ein naiver oder berechnender Mitläufer war, ist nicht eindeutig geklärt.

- Die Theorien von Konrad Lorenz zum angeborenen Instinktverhalten und zur Prägung gelten heute als überholt. Mittlerweile erklärt man das Verhalten von Tieren eher mit Hilfe der Soziobiologie, der Verhaltensökonomie und der Neurobiologie.

1935 schlüpfte die Graugans Martina aus ihrem Ei und wurde auf Konrad Lorenz geprägt. Ein Jahr später wurden sie und der Ganter Martin ein Gänsepaar. Ein weiteres Jahr später zogen die beiden Gänse davon und wurden nie wieder gesehen. Konrad Lorenz berichtet aber zeitlebens immer wieder über Martina, auch wenn er in all den Jahren seiner Forschung hunderte Graugänse beobachtet hat. Dabei wandelten sich die Anekdoten; das hat die Wissenschaftshistorikerin Tania Munz analysiert: In den Schriften von Konrad Lorenz hatte Martina „ein üppiges und wandelbares Leben geführt“. So schrieb Konrad Lorenz in den 1930er Jahren zunächst nur von „einer Gans“, um stereotypes Verhalten für die gesamte Gänseart darzustellen. Während der Nazi-Zeit wurden Martina und der Gänserich Martin als Beispiel für ein erfolgreiches Paar dargestellt und als Kontrast zu den domestizierten Gänsen, die angeblich gefährlich wären und einen stärkeren Sexualtrieb hätten. Später rückte dann Konrad Lorenz in seinen Schriften Martina als Individuum in den Vordergrund und stellte sich selbst als ihr Chronist dar. Und noch später stellte Lorenz in seinen Texten Martina als abnormal dar, mitsamt so einigen stressbedingten Verhaltensauffälligkeiten.

7. November 1903 Konrad Zacharias Lorenz wird in Wien geboren.

1922 – 1928 Medizinstudium an der Columbia University in New York und an der Universität Wien, inklusive Promotion.

1927 Hochzeit mit Margarethe Gebhardt, der Freundin aus Kindheitstagen. Das Ehepaar bekommt drei Kinder.

1928 – 1936 Zoologie-Studium an der Universität Wien, zweite Promotion, anschließend Habilitation. Parallel Stelle als Assistent am Anatomischen Institut.

1940 – 1941 Professur für Psychologie an der Universität Königsberg.

1941 – 1948 Wehrmachtssoldat und Kriegsgefangenschaft in der Sowjetunion.

1949 Veröffentlichung seines bis heute populärsten Buchs „Er redete mit dem Vieh, den Vögeln und den Fischen.“

1950 – 1955 Forschungsstelle für Vergleichende Verhaltensforschung der Max-Planck-Gesellschaft in Buldern, Westfalen.

1955 – 1973 Gründungsdirektor am Max-Planck-Institut für Verhaltensphysiologie am Eßsee in Bayern.

1973 Medizin-Nobelpreis zusammen mit Karl von Frisch und Nikolaas Tinbergen.

1985 Er ist der Namensgeber der Konrad-Lorenz-Volksabstimmung gegen ein Wasserkraftwerk. Zuvor wurde er Galionsfigur einer erfolgreichen Volksabstimmung gegen das Atomkraftwerk Zwentendorf in Österreich.

27. Februar 1989 Konrad Lorenz stirbt in Wien nach akutem Nierenversagen.

Fourteen-year-old Nils is lazy and constantly plays pranks. As punishment, he is turned into a gnome and travels across Sweden on the back of a gander, all the way up to Lapland. The Wonderful Adventures of Nils Holgersson with the Wild Geese is the name of this story, written by Selma Lagerlöf at the beginning of the 20th century. It was actually intended for regional studies lessons in Swedish schools. But in Austria, in Altenberg near Vienna, a little boy was also read this story.

The boy was only five years old, but the story stayed with him: “Since then, I have longed to become a wild goose; and when I realized that this was impossible, I desperately wanted to have one; and when it turned out that this was also impossible, I contented myself with having domesticated ducks.” This is how he remembers it almost seven decades later, when he receives the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine at the end of 1973, now an old man with a stately white beard: Konrad Zacharias Lorenz.

The scientist Lorenz became famous as the “father of geese.” And he went down in scientific history as much more than the co-founder of comparative behavioral research, known as ethology. But Lorenz the man was complex, and today his temporary proximity to Nazi ideology leaves a rather uneasy feeling.

Early fascination with geese

Perhaps everything would have turned out differently if Konrad Lorenz had not been a latecomer, born in 1903, 18 years after his brother Albert. Had he been older, the book about Nils and the geese, published in 1906, would probably not have fascinated him so much. Perhaps his life would also have taken a different course if his mother Emma had not bought two ducklings from a neighbor; one for little Konrad, his mallard, and one for Konrad's playmate Margarethe Gebhardt. The two played “duck parents” all summer long. And even then, Konrad noticed that his own duck followed him everywhere, while the other duck waddled after neither him nor Margarethe. Over time, the budding researcher turned the Lorenz family estate into a small zoo, with jackdaws in the attic and ducks in the garden pond.

Years later, Lorenz studied medicine at Columbia University in New York and at the University of Vienna – albeit rather reluctantly and only to please his father. He earned his doctorate, studied zoology, earned a second doctorate, and finally qualified as a professor. He married his girlfriend Margarethe; they had two daughters and a son. And he raised Martina, probably the most famous gray goose in the world.

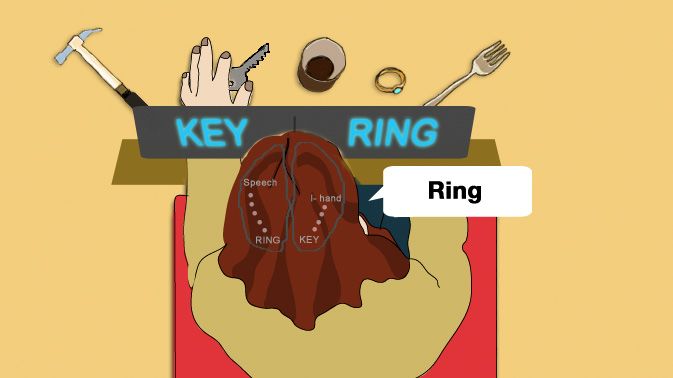

The principle of imprinting

The first thing Martina saw as a newly hatched chick was Konrad Lorenz: she is said to have raised her head and chirped at Lorenz. After a while, he wanted to push the chick under the mother goose's belly, but it only followed him – just like his first mallard duck once did. Every evening, Martina climbed the stairs to the bedroom with Lorenz and flew out the window the next morning. The researcher was convinced that Martina had been imprinted by him and was therefore fixated on him. He believed that chicks' tendency to follow someone was innate and therefore described this behavior as an instinctive movement. Normally, they follow their mother. But newly hatched chicks first have to learn who that is.

The mother is a large, mobile something that makes noises and is very close to you – because the mother would not let anyone else near her nest. But in this case, there was Konrad Lorenz, and the animal learned to consider him its mother. Thus, it was the human and not the goose that became the key stimulus – the stimulus that triggered the following behavior. Konrad Lorenz called the connection between instinctive behavior and learned stimulus the “innate triggering mechanism.” All of this together resulted in his concept of imprinting and his theory of instinct, which he presented in 1937 in his treatise On the Concept of Instinctive Action.

Comparative behavioral research

Konrad Lorenz himself called his field of research “animal psychology,” thus becoming one of the founding fathers of ethology – comparative behavioral research. It stood in contrast to classical behaviorism, which dominated psychology at the time and sought to explain all behavior through unconditioned and learned reflexes.

However, this contradicted Lorenz's observations of instinctive behavior – for example, when birds know how to peck at food grains without anyone having shown them how. Or when robins recognize a male intruder in their territory solely by its red color – and a simple tuft of red feathers is enough to trigger defensive behavior.

The road to Nazi Germany

Ethology was based on Darwin's fundamental assumptions: behavior, like anatomy, must have developed according to random variability and corresponding selection advantages. This proved to be a problem, because Darwin was not well liked in Austria in the 1930s – the country was strongly Catholic. Lorenz was banned from conducting his ethological research, so he left the University of Vienna and continued to work unpaid at home in Altenberg. In 1937, he applied for funding in Nazi Germany from the Emergency Association of German Science, a precursor to today's German Research Foundation. The application was rejected because “above all, the political views and ancestry of Dr. Konrad Lorenz were called into question.”

A few months later, Konrad Lorenz reapplied for project funding. Letters of recommendation from colleagues now attested that he was of Aryan descent, that “Dr. Lorenz's political views are impeccable in every respect,” that he had “never made a secret of his approval of National Socialism,” and that his biological research was in line with the views of the German Reich. Lorenz received the money and went on to research how the instinctive behavior of wild geese changes when they are bred as domestic animals or crossed with domestic geese.

In March 1938, the Germans marched into Austria. In June 1938, Konrad Lorenz applied for membership in the NSDAP. Two years later, he became professor of psychology in Königsberg, a position once held by Immanuel Kant. In 1941, he was drafted into the Wehrmacht, where he worked as a psychiatrist and neurologist in a military hospital in Poznan, Poland. He was later sent to the front and soon fell into Russian captivity. In 1948, Lorenz returned to his homeland, to Altenberg near Vienna.

“Racial hygiene defense”

In an interview on the occasion of his 85th birthday, Lorenz explained: "And I also shied away from all politics because I was preoccupied with my own problems. I also avoided any confrontation with the Nazis in a very contemptuous manner; I simply didn't have time for it." That was in 1988, shortly before his death, when Lorenz was a celebrated member of the Austrian environmental movement, warning against nuclear power plants, technologization, and ecological disasters.

His statements do not fit in at all with his activities as an army psychologist, who not only worked in the reserve hospital in Posen, but also conducted studies on “German-Polish mixed-race people.” He came to the conclusion that Polish genetic material was characterized, for example, by “fear of life, impulsive dynamics, and a lack of vital roots.” As a result, he feared that “physical and moral signs of decay, which cause the decline of civilized peoples after they have reached the stage of civilization, are essentially the same as the signs of domestication in domestic animals” and therefore called for a “conscious, scientifically-based racial policy.” The goal was the “improvement and enhancement of the people and race.” He speaks of “full-fledged” and ‘inferior’ individuals and advocates measures to “eradicate the inferior.”

Regarding his own research, he stated: “We confidently predict that these studies will be fruitful for both theoretical and practical racial policy concerns.”

All these statements come from Konrad Lorenz of the Third Reich. In 1981, however, he stated in a television interview: “I really didn't believe at the time that people meant murder when they said ‘extermination’ or ‘selection’. I was so naive, so stupid, so gullible – call it what you will – back then.”

Empfohlene Artikel

Nobel Prize

It is a dark, brown chapter in Konrad Lorenz's biography. Did he really adhere to Nazi ideology, or did he get lost in the homology between geese and humans and become a naive follower rather by accident? The Nobel Prize Committee is also said to have discussed this. In the end, Konrad Lorenz did indeed receive the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine in 1973, together with his colleague Nikolaas Tinbergen and zoologist Karl von Frisch, who had primarily studied the sensory perception of honeybees. The researchers received the prize “for their discoveries concerning the organization and triggering of individual and social behavior patterns.”

Outdated theories

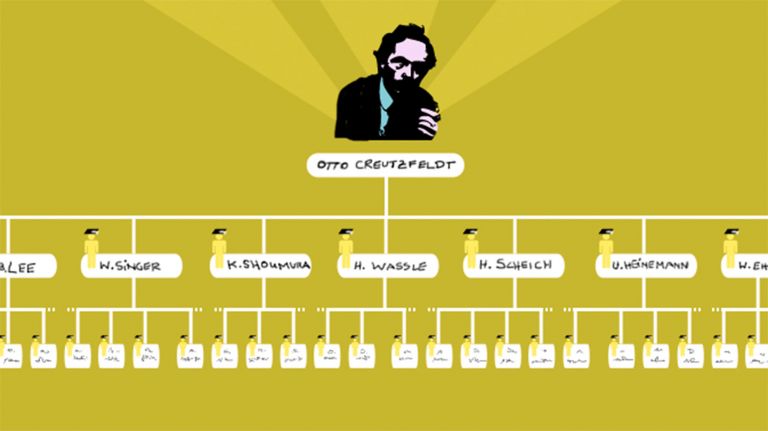

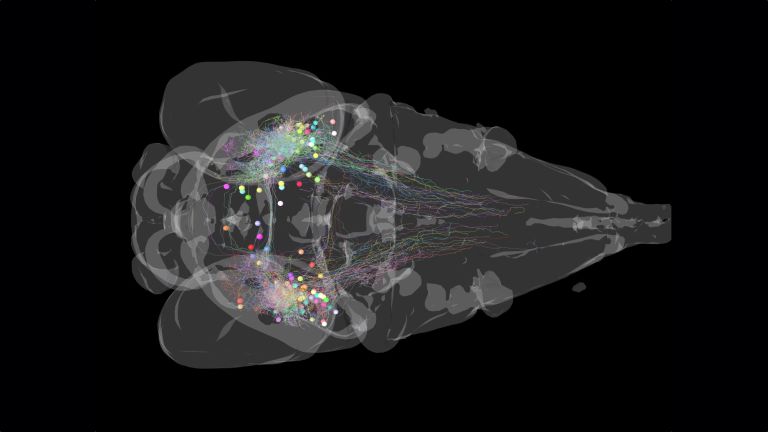

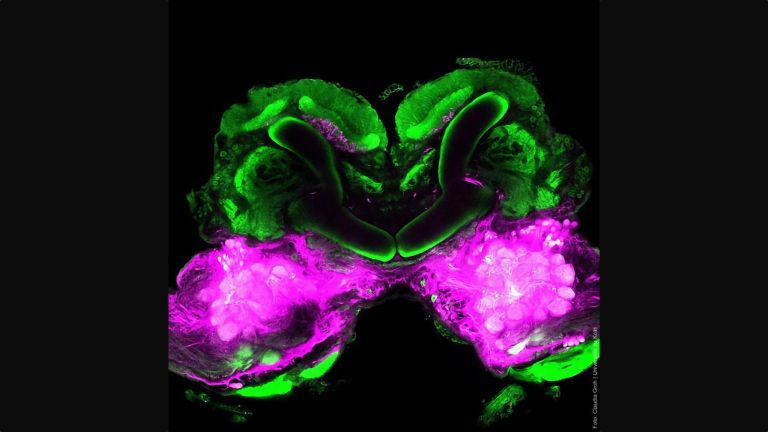

Lorenz disliked experiments: he wanted to study animal behavior through observation alone. And even though terms such as imprinting, instinct, and innate trigger mechanisms can still be found in many school textbooks, Lorenz's theories are now considered outdated. Nowadays, attempts are made to explain how the behavior of animals – and humans – is influenced from a socio-biological, behavioral-ecological, or neurobiological perspective.

On February 27, 1989, Konrad Lorenz died at the age of 85 after suffering acute kidney failure. Shortly before, he had dictated to his secretary: “The reputation of my contemporaries, especially the scientific ones, claims that I am a great man, and they must know better than I do. When I look back and try to highlight what I am proud of, the result is modest – honestly!” Such understatement was unusual for Lorenz. After all, he did win a Nobel Prize.

Further reading

- Munz, T: “My goose child Martina“: the multiple uses of geese in the writings of Konrad Lorenz. In: Historical Studies in the Natural Sciences, Vol. 41 (4), S. 405 – 446, 2011. Abstract