Smart Flies

Eat, forget, and flee – fruit flies react in very different ways in only slightly different experiments. They are "ultra-rational creatures," according to Magdeburg-based neurobiologist Bertram Gerber.

Scientific support: Prof. Dr. Marion Silies

Published: 18.01.2026

Difficulty: easy

- Larvae of the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster can be conditioned to a scent in just a few trials.

- However, the learned behavior is not automatically recalled. Fruit flies also weigh their options.

- They optimize their behavior so that they get as much and as varied food as possible.

- Understanding the fly brain could improve artificial intelligence.

It is not that difficult to teach even tiny fly larvae something: Bertram Gerber from the Leibniz Institute for Neurobiology in Magdeburg practices this every day. To do so, he places a small plastic container with a scent in a Petri dish. The researchers add an agar nutrient medium to the dish. The four-millimeter-long larvae of Drosophila melanogaster can move around easily on this “glaze." What's more, their favorite food, sugar for example, can be incorporated into the glaze. After a few rounds, the fly larva learns the connection between scent and sugar. By the third time at the latest, it crawls toward the scent it has learned.

It is a classic conditioning experiment that would yield similar results with other animals. It became famous with "Pavlov's dog": Russian Nobel Prize winner for medicine Ivan Petrovich Pavlov proved that a dog's mouth waters when it hears a bell ring. Provided, of course, that it has been conditioned to expect food shortly after the bell rings.

One can certainly envy the fly larvae for their docility. After all, we humans don't always need three attempts to remember a new word in a foreign language. And yet we tend to think of the little white larvae as dumb. "At first, it was assumed that the animal would automatically follow the scent it had learned," says Gerber. But are flies really such simple automatons?

Machines or clever animals?

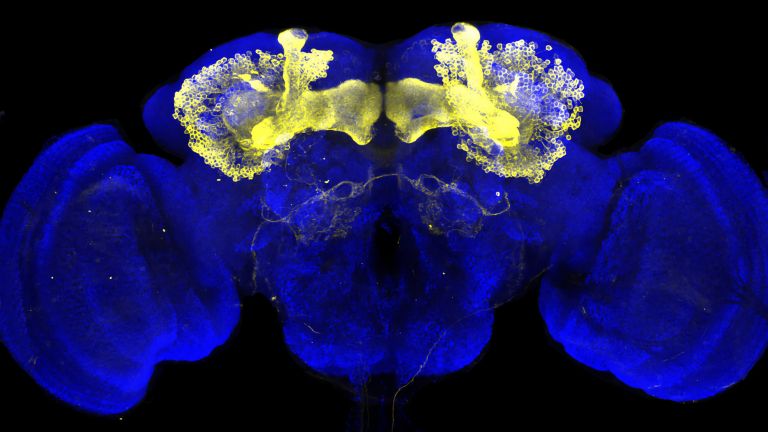

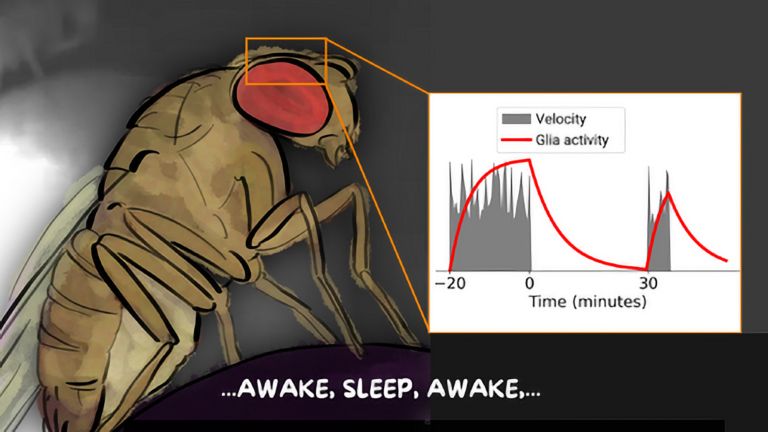

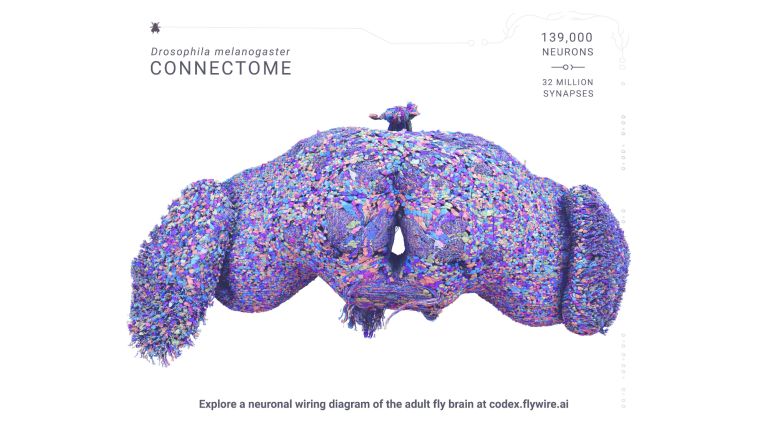

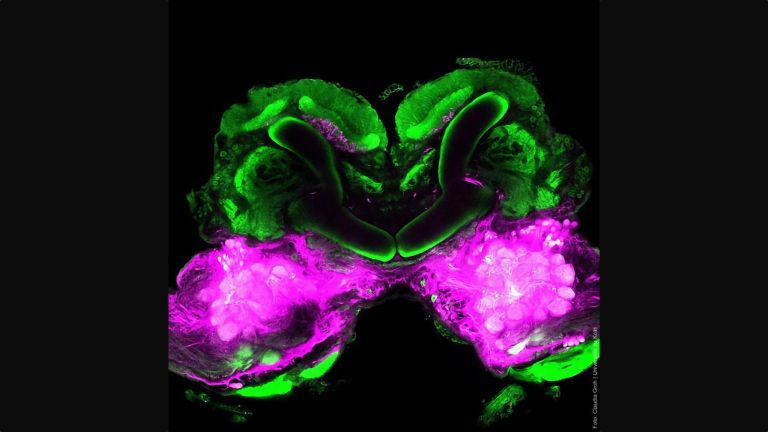

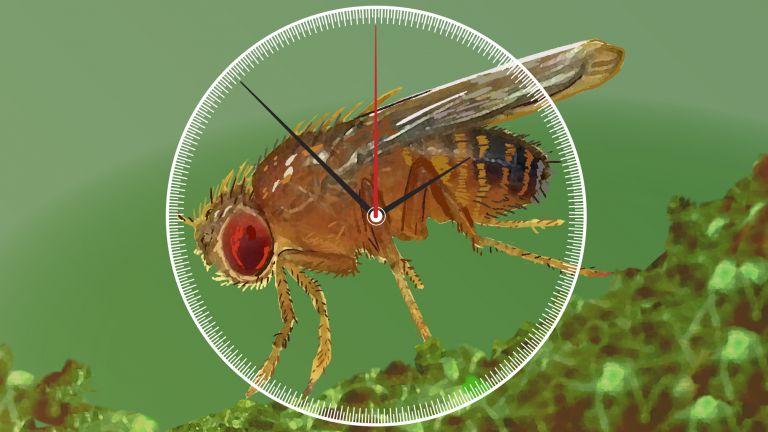

The idea of insects as automatons persists. The Tübingen botanist Wolfgang Engelmann already referred to fruit flies as "flying clocks" in his illustrious work on the life and death of these animals. They hatch punctually in the morning, all at once. They sleep at night and begin crawling around just as punctually at daybreak. This circadian, or daily rhythmic, behavior is controlled by a neural network that includes the mushroom body, an important structure in the fly brain. Among other things, this structure contains various photoreceptors that sense daylight. Fruit flies can also detect the ambient temperature and the Earth's magnetic field.

And yet, even fly larvae, whose brains consist of 10 times fewer nerve cells than those of adult flies, are not automatons, as Gerber was able to demonstrate in his experiments. "There is an intermediate step between retrieving a memory trace and acting on it. As a result, the larva behaves in a surprisingly smart way."

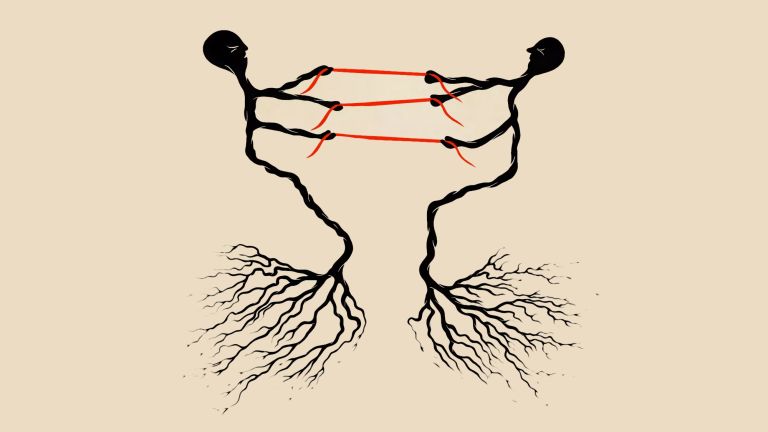

Prior to this discovery, Gerber was looking for the answer to a specific question: Do larvae conditioned to "scent sugar" automatically crawl toward the scent because they like the scent or because they expect to find sugar there? "That may sound like splitting hairs, but it's a difference in psychological terms – and also in the brain," he explains.

In order to identify the larvae's motives, his team presented the larvae with the scent on one side of the Petri dish in the final test, but at the same time sweetened the glaze. If the larvae were automatically attracted to the learned scent, they should also migrate to the scented side of the Petri dish under these circumstances – but they should not do so if they are interested in the sugar expected at the location of the scent, because after all, the sugar is already present in this test situation. And indeed, the larvae only displayed their search behavior when they did not already have what they were looking for. The learned attraction of the scent therefore actually stems from the expected food reward.

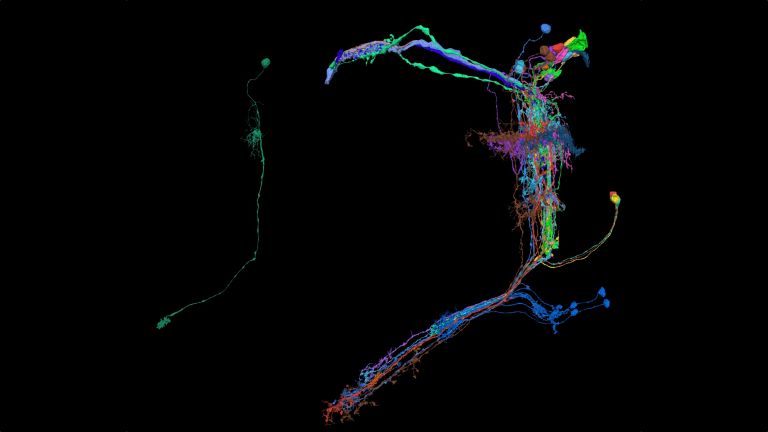

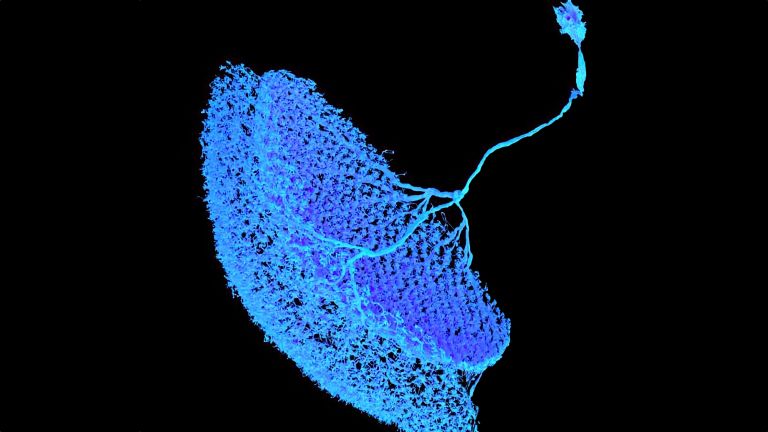

Always following the food

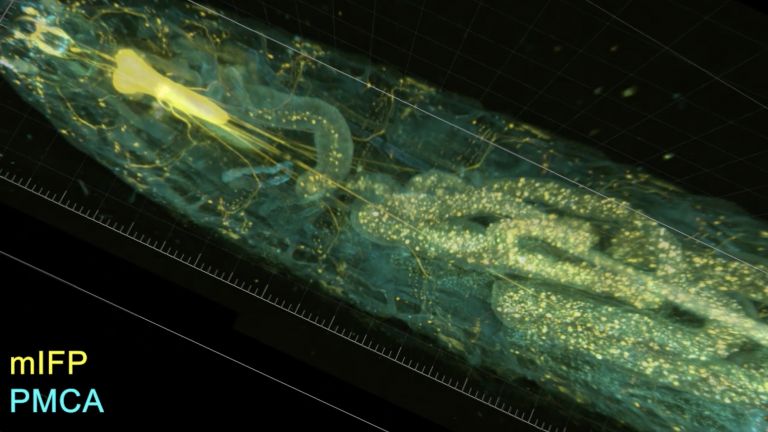

At the brain level, this differentiated behavior is by no means trivial – the memory trace becomes behaviorally effective when the larva does not yet have the expected food. In the other case, when it has already found the sugar, the same memory trace does not trigger learned behavior. Gerber's team recently identified a dopaminergic neuron in the mushroom body of the flies that could be responsible for this regulation of learned behavior. It is abbreviated DAN-i1. Its extensions reach into the mushroom body itself and ensure that the fly first learns the association between scent and sugar. On the other hand, it is also connected to the output neurons of the mushroom body, which control behavior, so that the fly can also suppress the impulse to crawl toward the scent. "It's like an elegant servo in a vehicle. DAN-i1 regulates both whether a memory trace is created and whether it is translated into learned behavior."

The larva thus appears to behave like a human being when eating. If we were sitting in a restaurant at a set table with the dish we had ordered, continuing to search for that very dish would, at best, seem strange.

The outcome of another experiment also shows that the larvae are surprisingly "rational." If they are sitting on a sweet surface but with less sugar than was served in combination with the scent during training, the larva continues its search. "The prospect of more – greed – drives them," Gerber explains. And even if they find a reward in the test situation that is equivalent to sugar but different, such as a nutritious amino acid, they continue to search: after all, they can still obtain the sugar in addition to the amino acid that is already present.

The experiments can be interpreted to mean that the small larvae always minimize their motor effort and maximize the amount and diversity of food. After all, their biological purpose is to grow and eventually pupate.

The behavior of the small insect in the various experiments teaches us one thing above all: even Drosophila larvae are by no means automatons. They learn quickly and are astonishingly flexible and "rational" in applying what they have learned to their best advantage in any given situation.

How this could improve AI

However, there is one limitation to all the experimental studies on Drosophila, whether on larvae or adult flies: in many respects, the laboratory does not correspond to the biological environment. For example, odors in the air form plumes that fruit flies buzz through and react to immediately if they associate them with food.

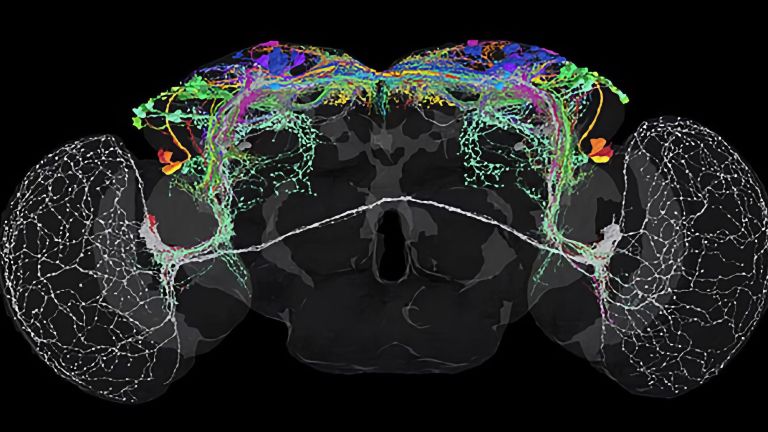

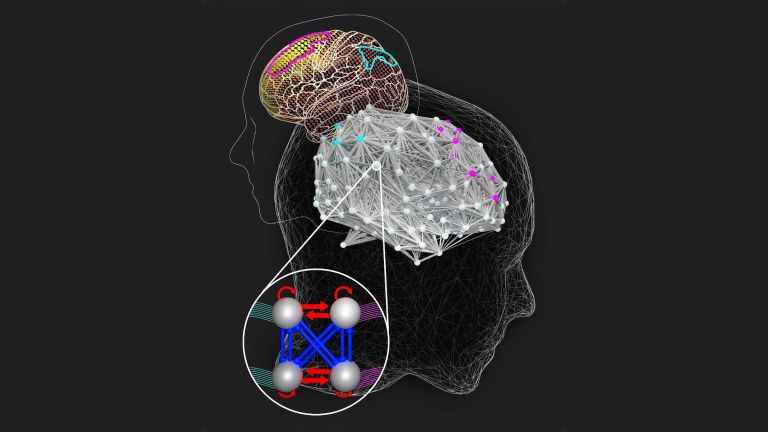

To better understand the complex behavior of insects, the working group led by Martin Paul Nawrot, a physicist at the University of Cologne, has begun to replicate the mushroom bodies of the animals in a computer ▸ Fly brain in a computer. In November 2020, he succeeded in proving this by programming the virtual nerve cells in such a way that the animals create a memory trace for the scent even in simulated scent clouds if it is associated with a reward in the form of food.

"We also assume that the animals have a long-term memory in which they remember things for longer than 24 hours, and in parallel to this, probably a short-term memory in other neurons," explains Nawrot. He wants to integrate both into his digital Drosophila brain in the future in order to understand what information the animal stores and retrieves and how.

"The difference between short-term and long-term memory is central to living beings. And fruit flies are the best way for us to understand it." Nawrot could even imagine applications for these findings that go far beyond flies: in artificial intelligence, no distinction has been made between short-term and long-term memory until now. It is quite possible that one day the fly will teach us to build smarter robots.

Recommended articles

Further reading

- Nawrot, M.; Rapp, H.: A spiking neural program for sensorimotor control during foraging in flying insects. PNAS, 2020, 117(45), https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.2009821117

- Schleyer, M. et al.: Identification of Dopaminergic Neurons That Can Both Establish Associative Memory and Acutely Terminate Ist Behavioral Expression. Journal of Neuroscience, 2020, 40(31), https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32586949/

- Schleyer, M. et al.: Learning the specific quality of taste reinforcement in larval Drosophila. Elife, 2015, https://elifesciences.org/articles/04711