The Cortex

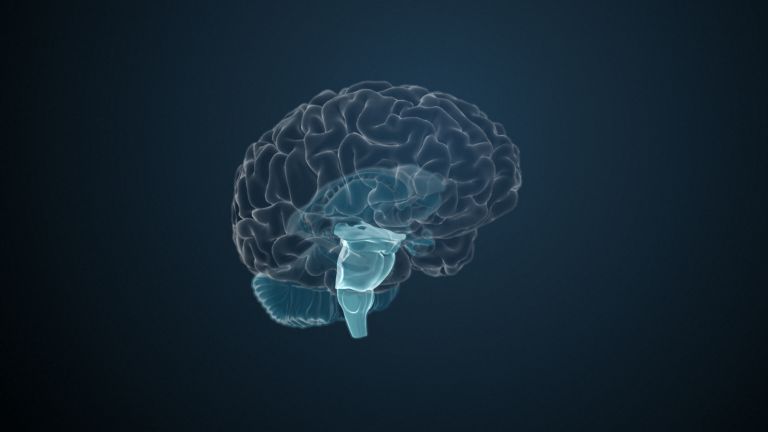

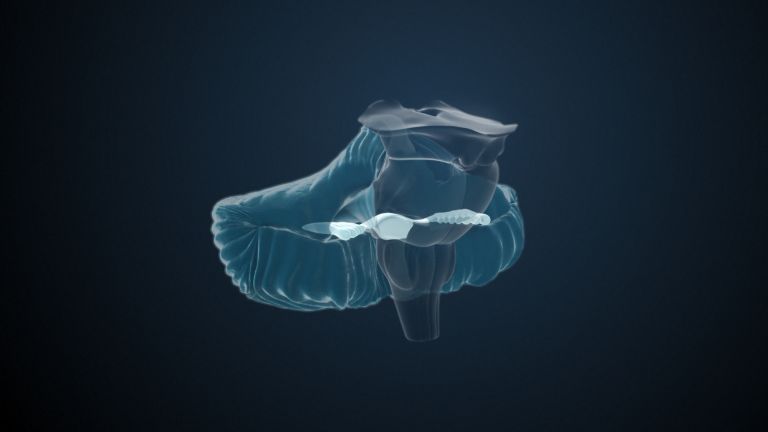

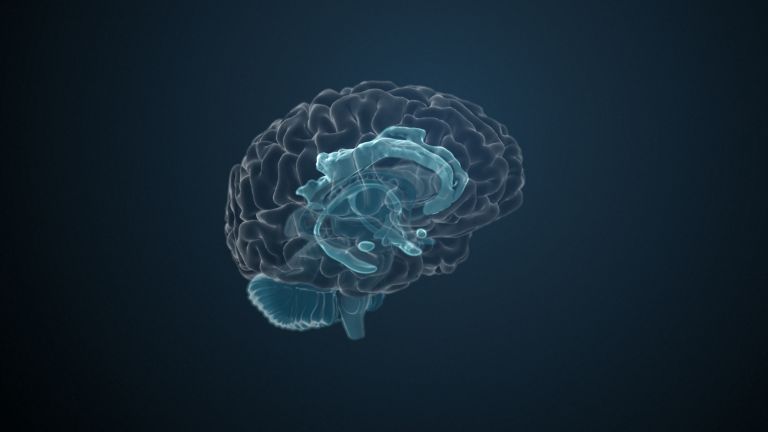

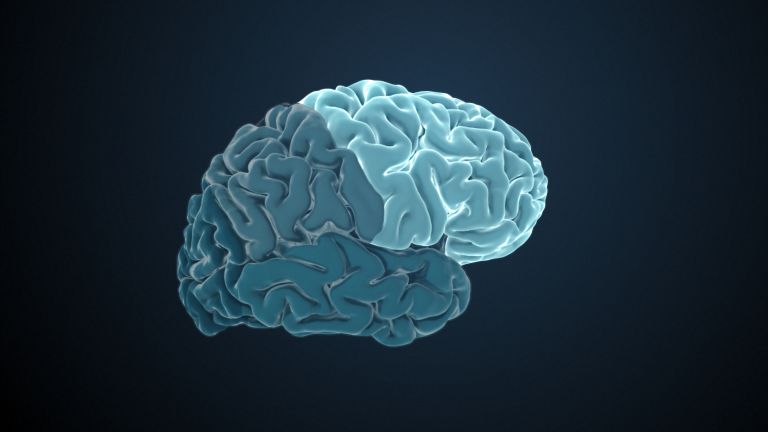

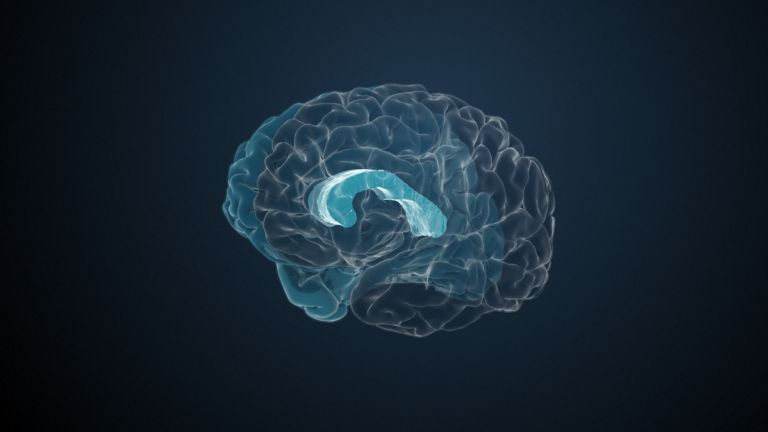

Even non-anatomists have this characteristic image of the brain in their minds: a helmet-shaped structure with a surface covered in convolutions and furrows. This outermost part of the brain – well protected by the skull and the meninges underneath – is the cerebral cortex. It usually is referred to simply as the cortex, the Latin word for “bark.”

Wissenschaftliche Betreuung: Prof. Dr. Karl Zilles, Prof. Dr. Andreas Vlachos

Veröffentlicht: 20.09.2025

Niveau: mittel

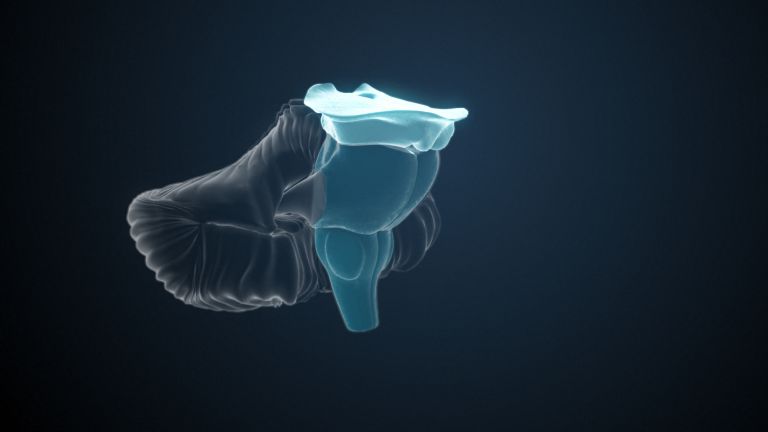

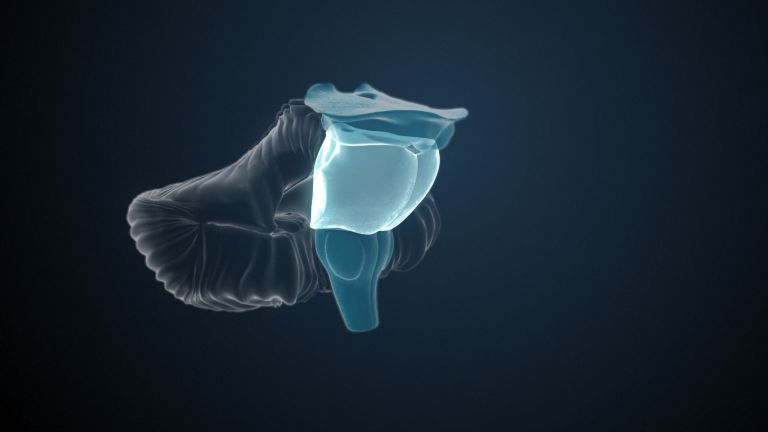

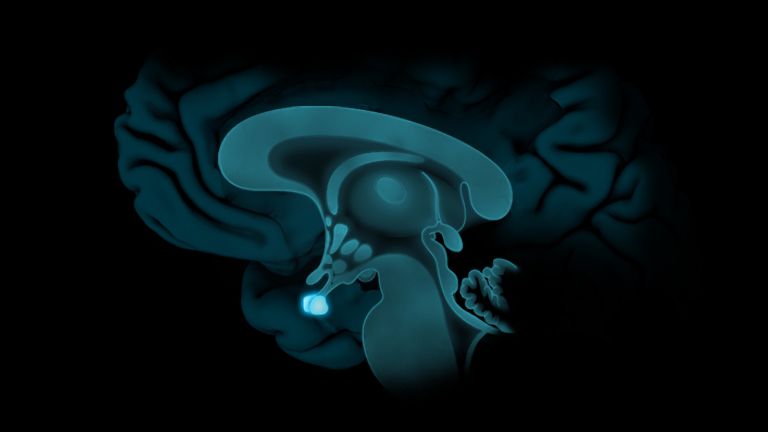

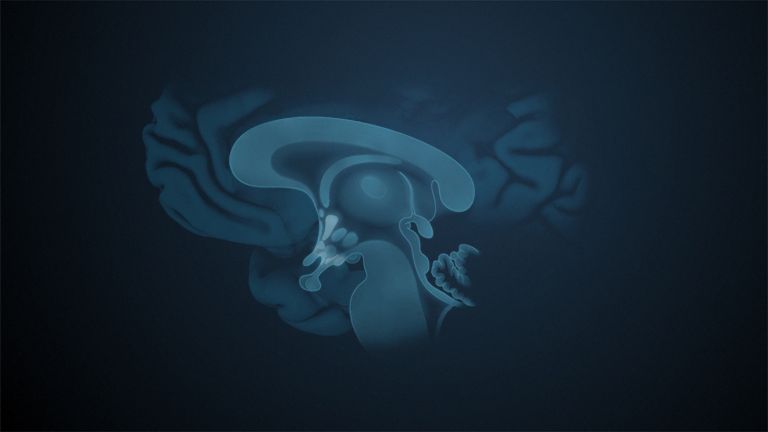

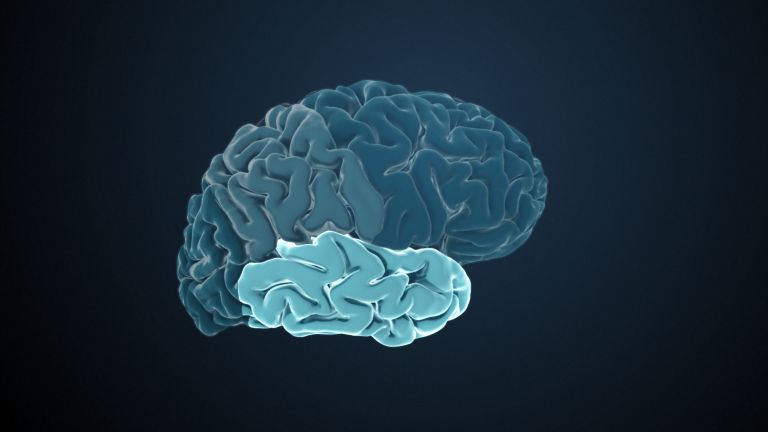

Die Rinde des Großhirns – der Cortex cerebri – bedeckt fast das gesamte von außen sichtbare Gehirn. Sie ist stark gefaltet und durchzogen von zahlreichen Furchen, wodurch voneinander abgrenzbare Bereiche entstehen. Jede Großhirnhälfte (Hemisphäre) gliedert sich in vier von außen sichtbaren Lappen, die Lobi: den Stirnlappen (Frontallappen), Scheitellappen (Parietallappen), Schläfenlappen (Temporallappen) und Hinterhauptslappen (Okzipitallappen). Hinzu kommt der Insellappen (Lobus insularis), der tief in der seitlichen Großhirnfurche verborgen liegt und von außen nicht sichtbar ist. Etwa 90 Prozent des Cortex bestehen aus dem evolutionär jungen Neocortex, der durchgehend aus sechs Zellschichten aufgebaut ist. Die entwicklungsgeschichtlich älteren Anteile – der Paleocortex und der Archicortex –unterscheidet sich dagegen durch ihren „einfacheren“ zellulären Aufbau.

Der Cortex ist die biologische Grundlage all unserer höheren geistigen Fähigkeiten.

Cortex

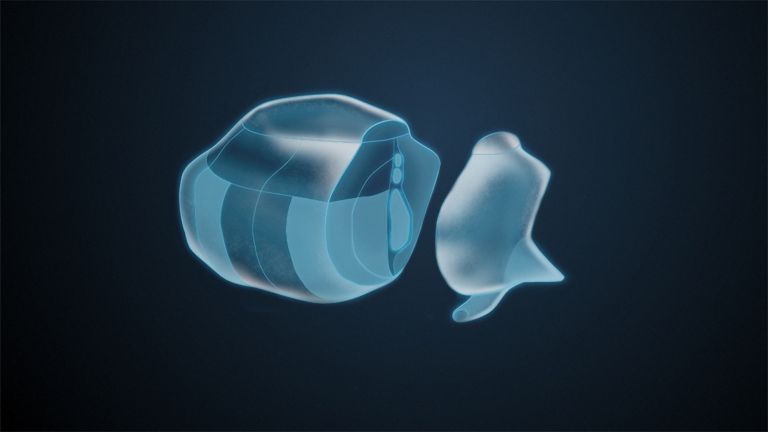

Großhirnrinde/Cortex cerebri/cerebral cortex

Cortex bezeichnet eine Ansammlung von Neuronen, typischerweise in Form einer dünnen Oberfläche. Meist ist allerdings der Cortex cerebri gemeint, die äußerste Schicht des Großhirns. Sie ist 2,5 mm bis 5 mm dick und reich an Nervenzellen. Die Großhirnrinde ist stark gefaltet, vergleichbar einem Taschentuch in einem Becher. So entstehen zahlreiche Windungen (Gyri), Spalten (Fissurae) und Furchen (Sulci). Ausgefaltet beträgt die Oberfläche des Cortex ca 1.800 cm2.

Archicortex

Archicortex/-/archicortex

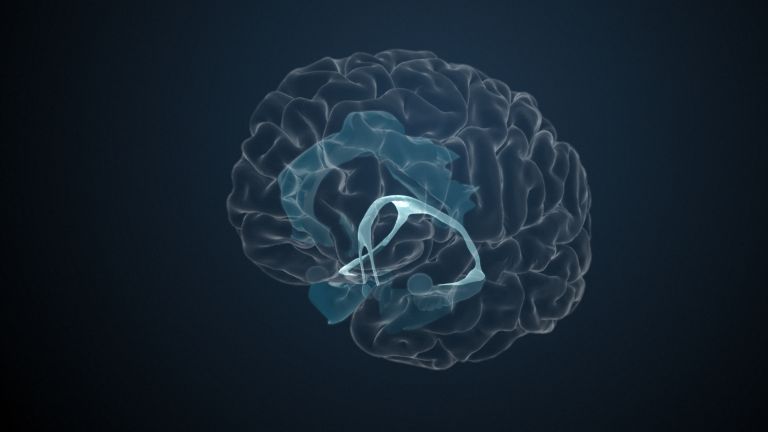

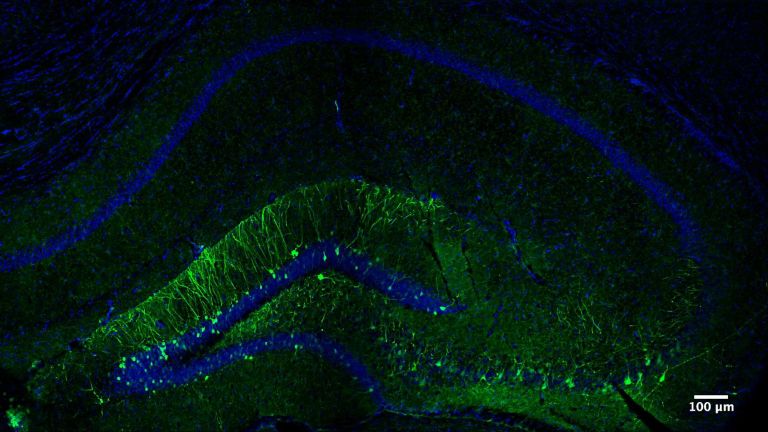

Eine entwicklungsgeschichtlich alte Struktur des Großhirns, die im Gegensatz zum Isocortex (auch Neocortex genannt) dreischichtig aufgebaut ist. Zum Archicortex gehören hauptsächlich die hippocampalen Strukturen.

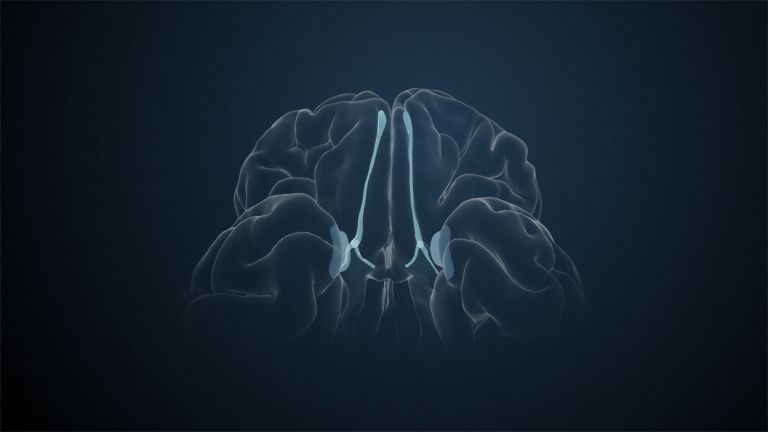

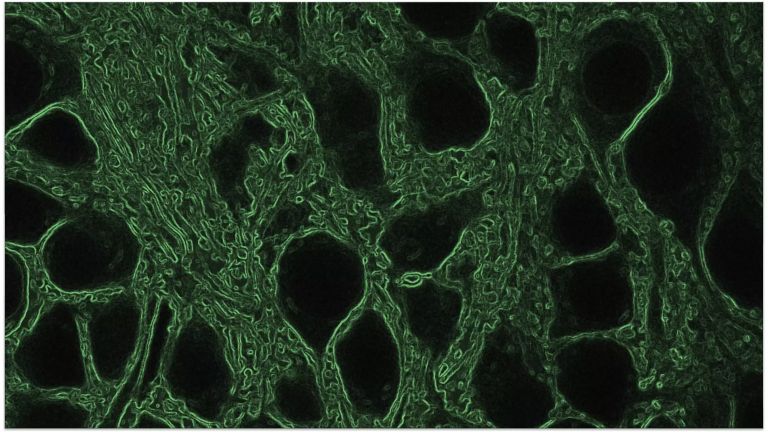

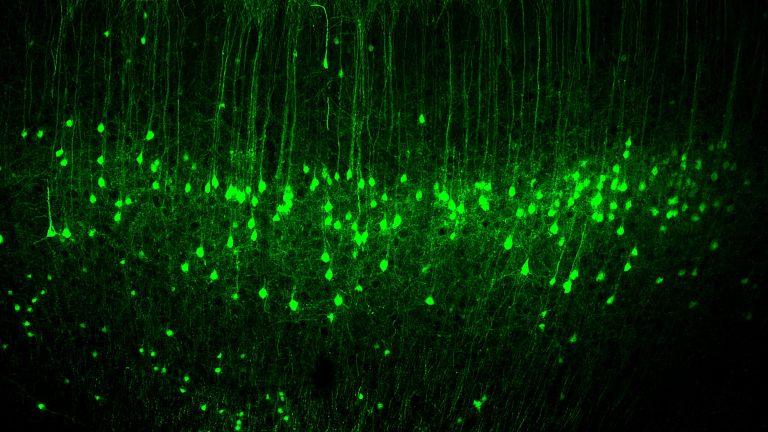

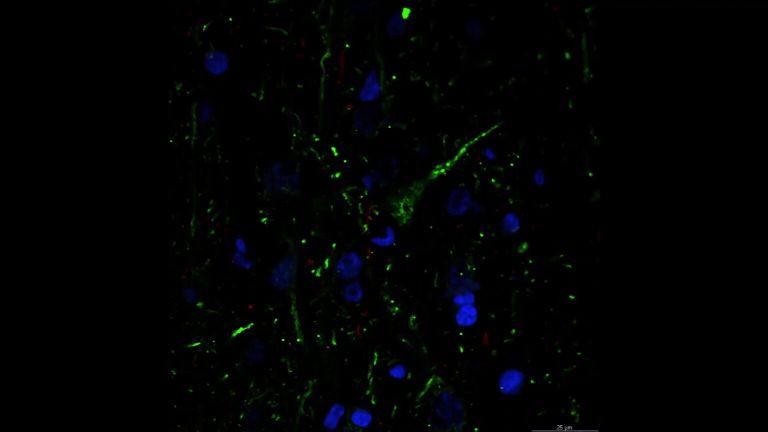

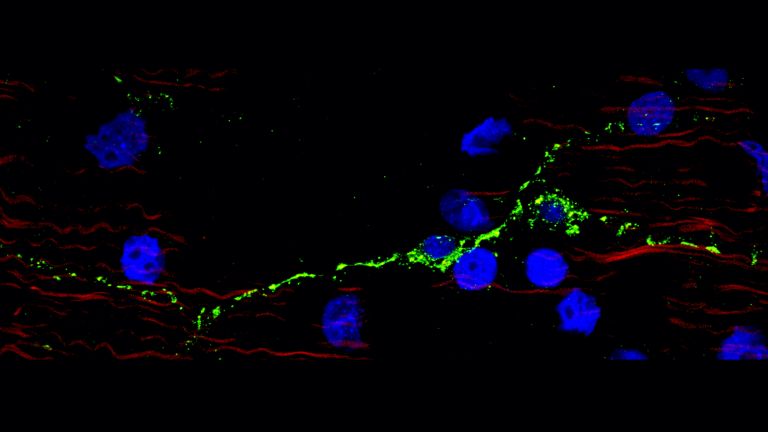

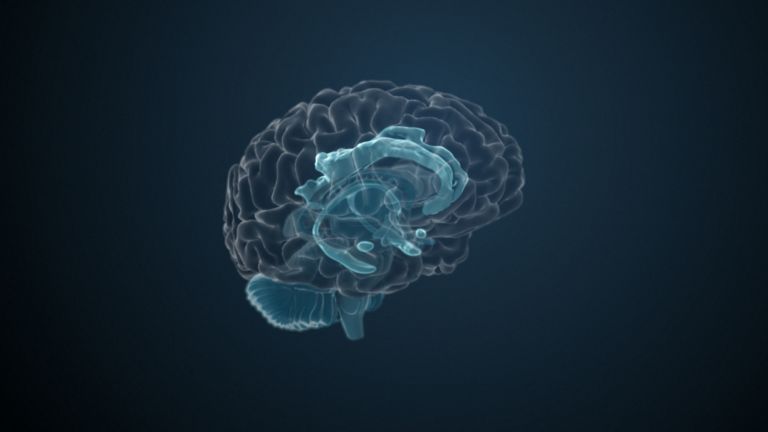

The cerebrum, with its two hemispheres and the corpus callosum connecting them, is the youngest and largest part of the brain in terms of evolutionary development. It accounts for about 85 percent of the total brain mass. If we remove the cerebral medulla – consisting mainly of nerve fibers and the basal ganglia (nuclei basales) embedded in it – we are left with the cerebral cortex, a two- to five-millimeter-thick layer known as gray matter. It is rich in nerve cell bodies, which give it a reddish-brown to gray color. Estimates suggest that there are around 17 billion nerve cells (neurons) in the human cerebral cortex. Individual differences between women and men are primarily related to the larger average brain and body size of men – they do not allow any conclusions to be drawn about mental abilities.

So, size does not matter. But mental abilities do: in the cortex, signals from the sensory organs and upstream brain regions are combined to form a coherent impression of the environment. It can also store information, thus forming the biological basis of our memory. Thinking, goal-oriented action, feelings – in short, all higher mental and psychological functions of humans – are not possible without the cerebral cortex.

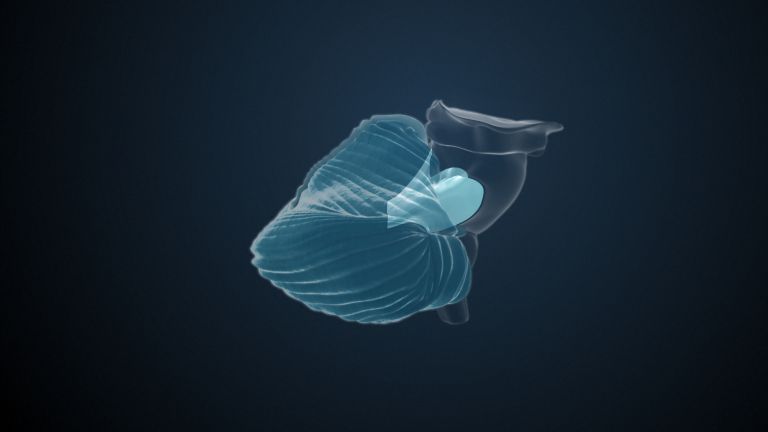

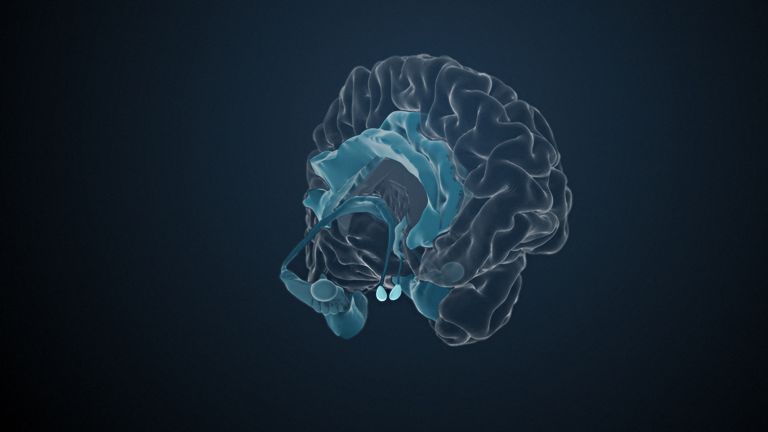

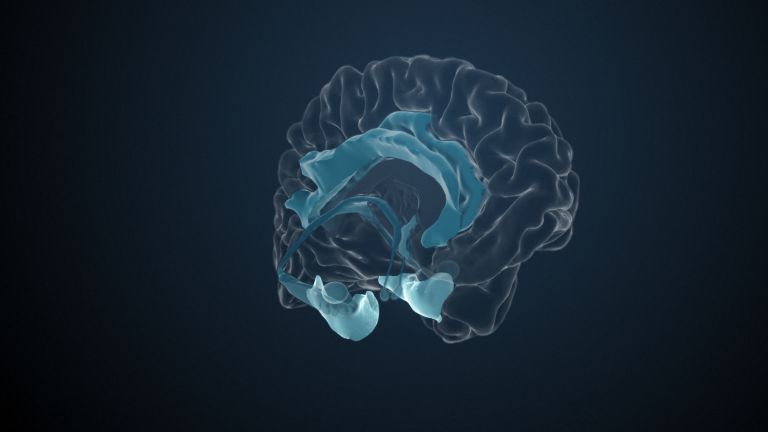

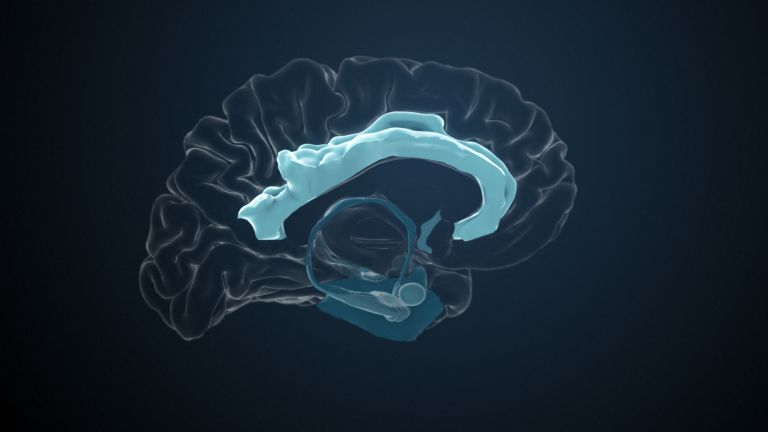

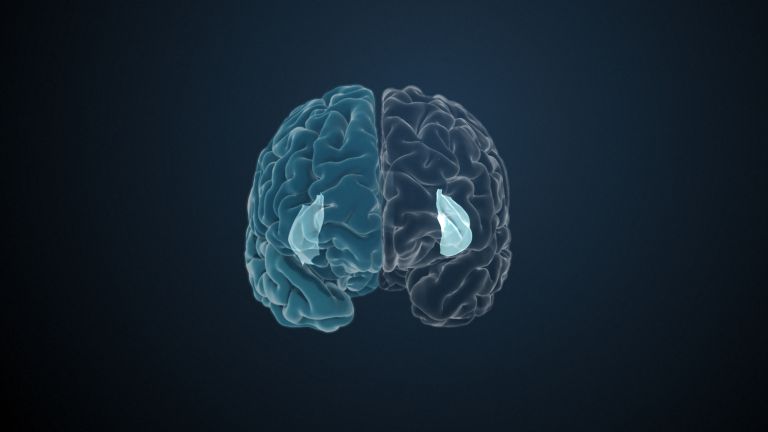

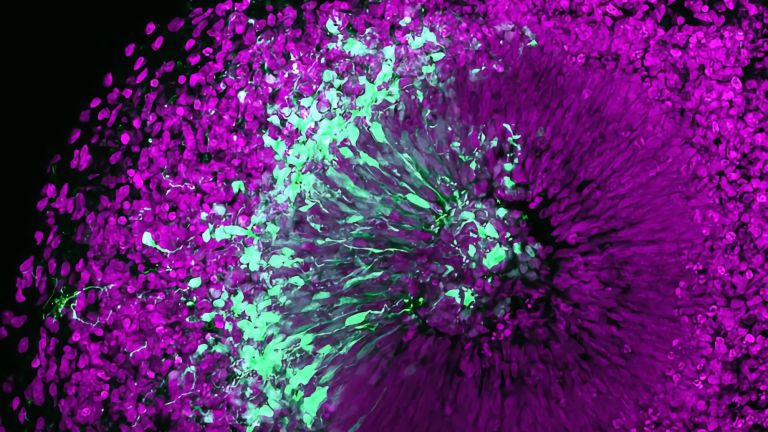

The evolution of intelligence and consciousness

The typical structure of the cortex has slowly developed into its present form over the course of mammalian evolution. First, the part responsible for smell perception developed – it is therefore called the paleocortex, or old cortex. The so-called Archicortex also developed very early on. It is often counted as part of the limbic system and, in humans, comprises parts of the cerebral cortex that are responsible for emotional responses, behavior for species preservation, and reproduction. In addition, there is the hippocampus, which is of central importance for memory and spatial orientation.

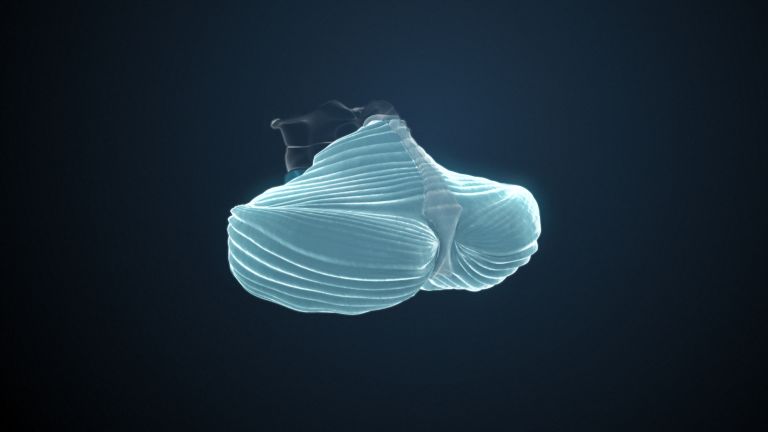

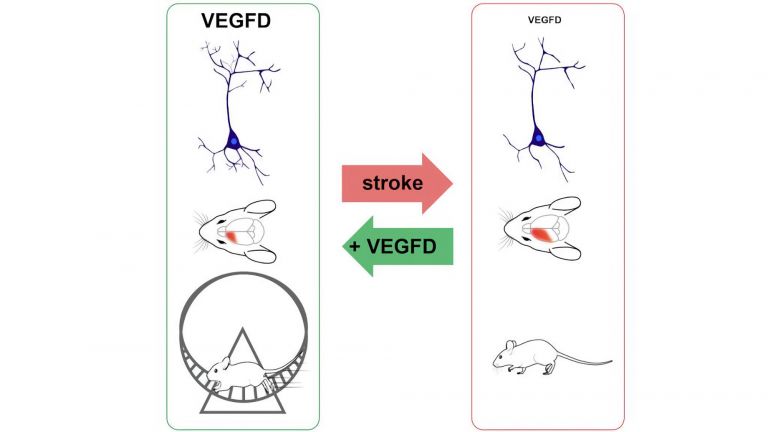

However, these “old” areas only make up about one-tenth of the cerebral cortex. The remaining 90 percent form the neocortex. With the increasing development and refinement of the senses in mammals – which include not only the eyes, ears, and taste organs, but also the sensory receptors in the skin, mucous membranes, and muscles, as well as the retina and inner ear with the hearing and balance systems – the neocortex became increasingly complex as well. In addition to motor areas for controlling specific movements, it primarily comprises large sections of the so-called association cortex.

In the association cortex, information from the many sensory systems is combined to form a comprehensive picture of the world; this is also where our attention and activity are regulated. The association cortex not only processes sensory impressions that enter the brain from outside, but also incorporates internal processes such as memories, expectations, and thoughts. This creates an internal model of the world that guides our perception and enables us to interpret the outside world in light of our experiences and goals.

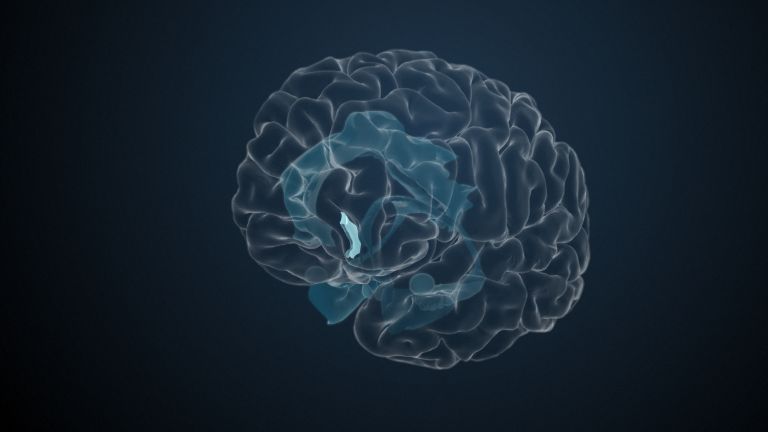

The cortex could not grow arbitrarily, because the volume of the skull is limited. Instead, it formed folds: convolutions (gyri) and furrows (sulci or fissurae). Similar to a crumpled dishcloth in a glass, this creates a large surface area in a small space – a trick of evolution to create enough space for the cortex's diverse tasks despite the limited volume of the skull. This, for its part, must be minimized, as only limited space is available due to the width of the female birth canal. Folded in this way, the cerebral cortex alone takes up almost half of the total brain volume.

Archicortex

Archicortex/-/archicortex

Eine entwicklungsgeschichtlich alte Struktur des Großhirns, die im Gegensatz zum Isocortex (auch Neocortex genannt) dreischichtig aufgebaut ist. Zum Archicortex gehören hauptsächlich die hippocampalen Strukturen.

Empfohlene Artikel

Structure and function

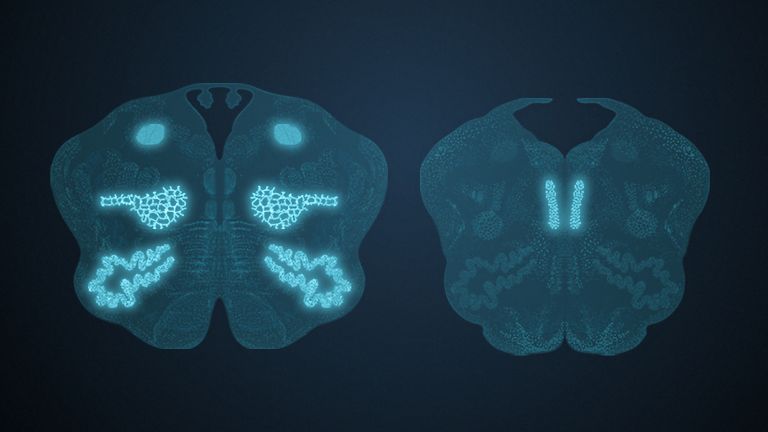

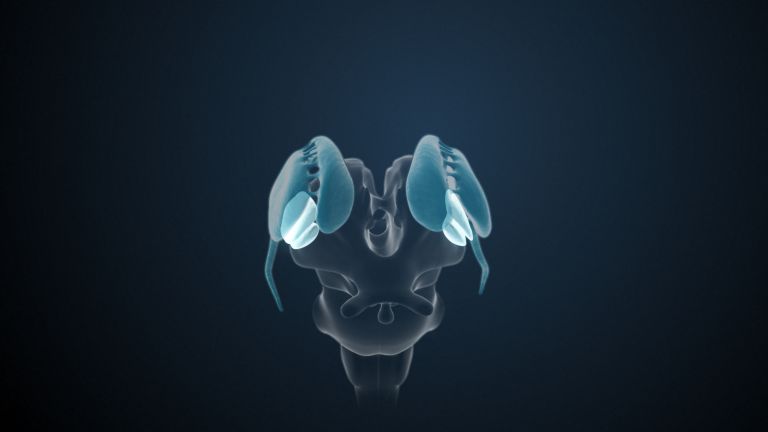

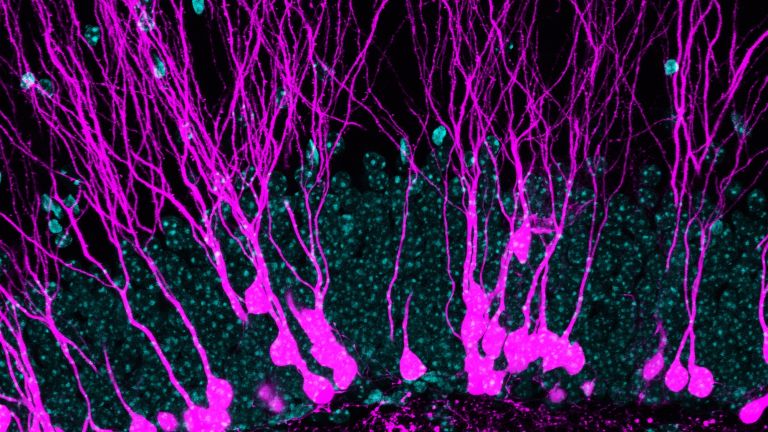

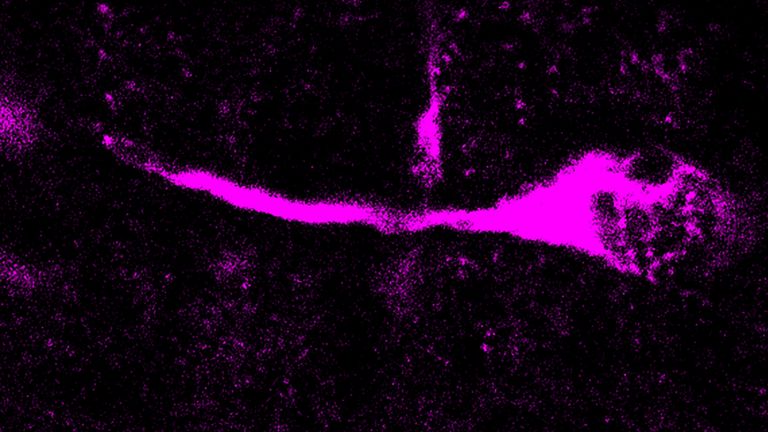

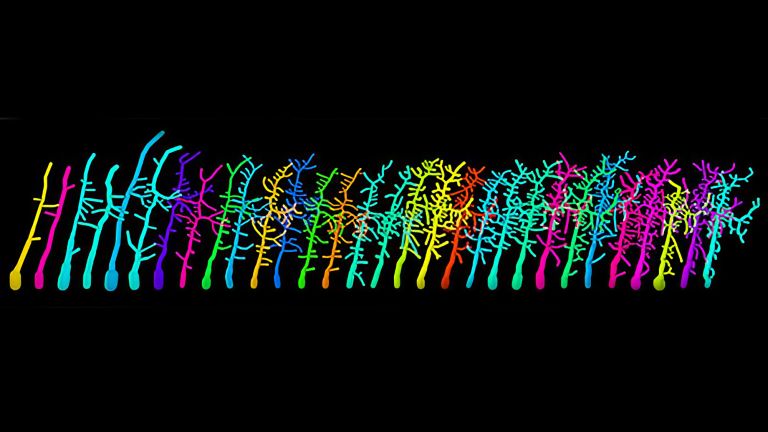

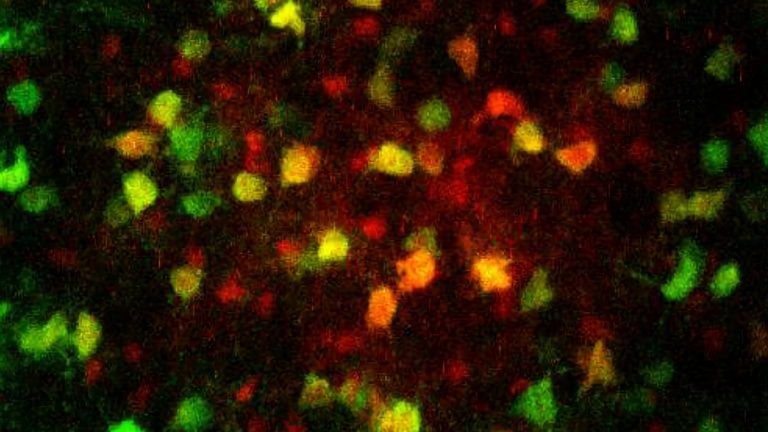

Under the microscope, the neocortex shows a typical six-layer structure. The exact characteristics of these layers vary depending on the region and are characteristic of certain cortical areas. The older parts of the cortex, on the other hand, do not have six layers, but a different number – usually three to five. This cellular organization is referred to as cytoarchitecture.

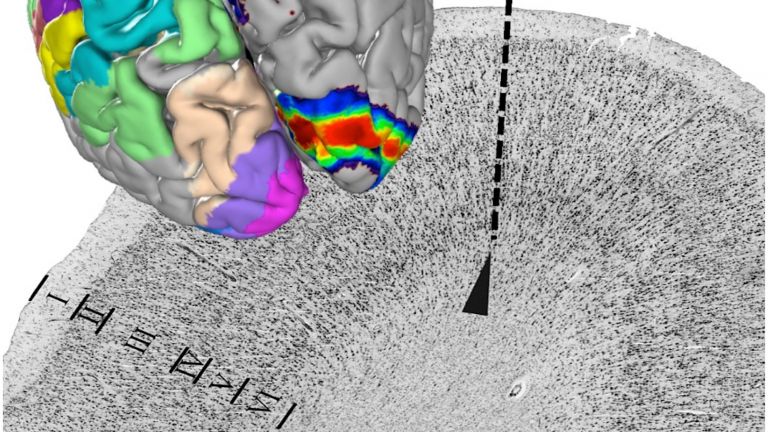

The large sulci and gyri can be used for rough orientation. However, a more precise classification can be traced back to the work of Korbinian Brodmann and Cecile and Oskar Vogt. Based on the subtleties in human cellular structure, Brodmann distinguished 52 areas, which are still known today as Brodmann areas. Some descriptions cite different numbers, as individual areas were not clearly defined at the outset. In modern research, Brodmann's fields have been further differentiated or combined.

Although Brodmann described his areas exclusively in terms of cellular structure, many of them can be assigned specific functions. For a long time, this was considered an example of the principle of “form follows function”. Today, however, there is debate as to whether the opposite might also be true: that functional networks shape the structure. In any case, the areas never work in isolation but are hubs in a dense network that connects different regions of the brain.

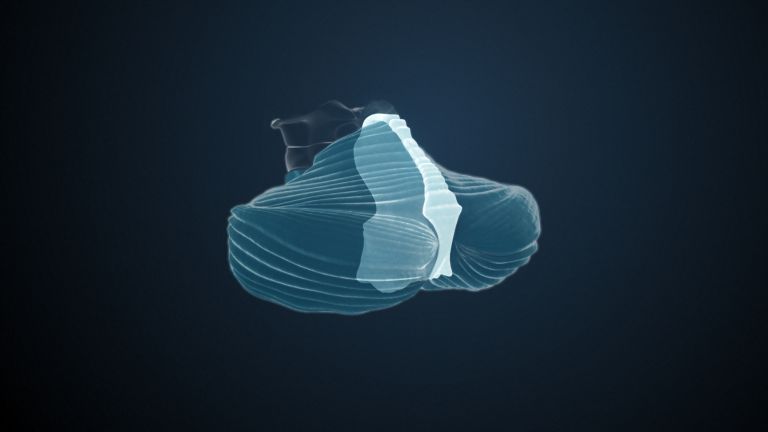

Cortical processing

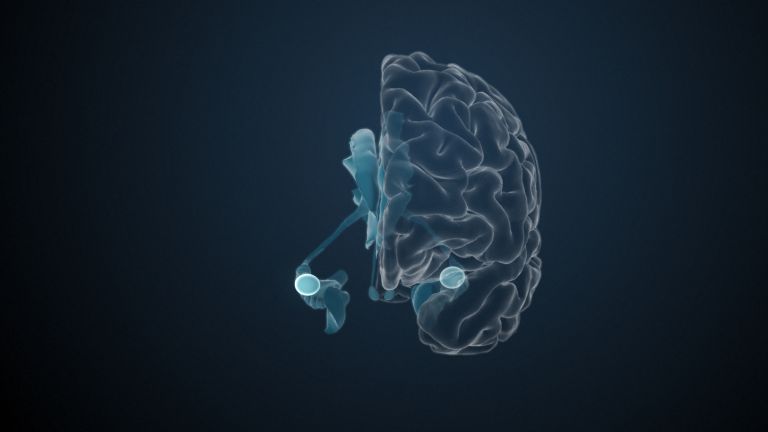

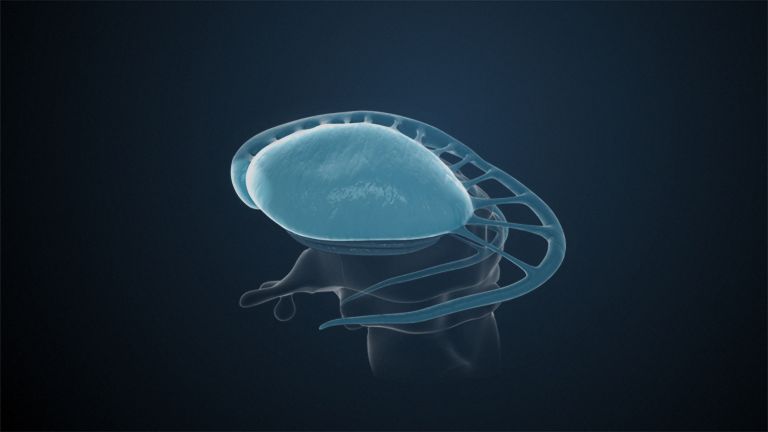

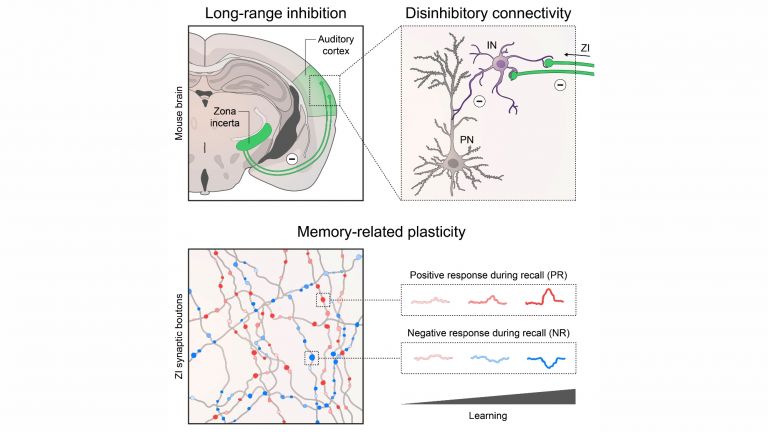

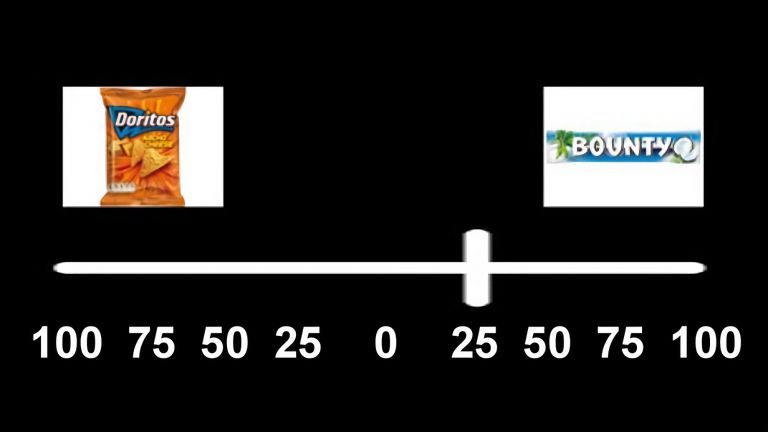

Whether we hear, see, or consciously perceive something in any other way, the signals from the various sensory organs end up in the cortex. But how exactly does this work? Incoming signals are switched by nerve cells in the thalamus and forwarded to the corresponding cortical regions.

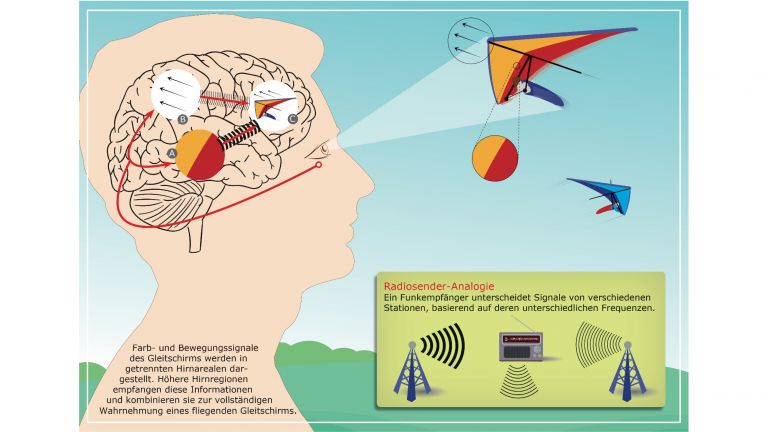

In the case of vision, for example, the primary visual cortex in the occipital lobe is activated. It processes the visual signals and forwards them to cortical regions that enable complex tasks such as the recognition of objects or faces. Primary somatosensory areas in the parietal lobe receive sensory information about touch, vibration, pressure, stretching, or pain, process it, and forward it to “higher” cortical areas, where, for example, touching an object gives rise to an idea of its shape. The same applies to hearing: the perception of different sound frequencies in the primary auditory cortex in the temporal lobe can give rise to the perception of a melody or speech in “higher” cortical areas.

Just as the sensory centers are responsible for sensory impressions, the motor centers are responsible for controlling movements. There, certain parts of the body, even individual muscle groups and movements, can be assigned to specific areas – for example, the right hand to an area in the left frontal lobe. Conduction systems provide the connection to the deeper parts of the brain and ultimately to the respective part of the body.

Significance of the cerebral cortex

The diverse functions of the cerebral cortex give rise to the possible consequences of local injuries and failures. If the primary visual center is affected, blindness occurs despite functioning eyes; if certain “higher” cortical areas fail, the person can see but, depending on the location of the disorder, cannot recognize faces, colors, or movements. Damage to the posterior third of the inferior gyrus in the frontal lobe, the Broca's area, impairs the ability to speak. And lesions in the front part of the frontal lobe lead to personality changes and a reduction in intellectual abilities.

Individual functions can therefore be assigned to areas of the cortex – which, however, never act independently and on their own, but are interconnected in complex ways with other areas and other parts of the brain. Recent studies show, for example, an astonishing interaction of feedforward and feedback between the visual thalamus and different layers of the primary visual cortex. This interaction is so detailed that both must essentially be considered as one system.

So whether it's a matter of deciphering and understanding a text like this one, or other higher mental functions: the cortex, the outermost layer of our two cerebral hemispheres, is responsible. This is where sensory impressions are processed, information is stored, we think and develop plans, our brain controls actions such as walking, speaking, or writing, and our consciousness arises. How exactly all this happens is the subject of intensive research.