What are Emotions?

Emotions make life worth living and are a central part of our inner life. But they are even more than that: they are powerful evaluation systems that allow us to automatically assess many situations so that we can react quickly and correctly.

Scientific support: Prof. Dr. Alfons Hamm

Published: 11.09.2025

Difficulty: easy

- Emotions involve more than just the subjective experience of feeling. They link physical and mental processes and thus prompt us to act.

- Emotions are difficult to suppress. In addition, we are very good at recognizing whether people are really feeling an emotion or just pretending.

- Research has developed various theories of emotion and examined numerous emotions, especially fear. However, because emotions are experienced very subjectively, research is difficult.

- When emotions run wild, they can have a very negative impact on the lives of those affected, for example in cases of depression, anxiety disorders, or post-traumatic stress disorder.

We've all been there: an important exam is about to start in a few minutes. You feel tense and nervous. You can't think about anything else, you stare at the teacher who is about to hand out the exam papers, you go over what you've memorized again and again in your mind. Your heart is pounding, your hands are sweaty. Your body is fidgety or paralyzed, and you may have to suppress the urge to just get up and leave. Even an uninvolved person who accidentally enters the room would clearly notice the examinee's state: the wide eyes, the crouched, tense posture, and possibly the thin, shaky voice.

Exam anxiety is a complex condition. Physical processes and behavioral impulses play a role, as does conscious subjective experience. And this does not only apply to fear; it is typical of all emotions to link physical and mental processes, influence the person as a whole and, in extreme cases, can completely captivate them. This is also reflected in many idioms: we are paralyzed with fear, blush with shame, jump for joy, are blind with rage.

More than a feeling

The feeling, i.e., what we consciously experience as fear, joy, anger, or sadness, is only the tip of the iceberg. Just as with the floating ice giants, much remains hidden from us in emotional processes. This is because emotions not only affect subjective experience but also include physical reactions to certain triggers that prepare people for a certain behavior and prompt them to act. For example, the sight of a snake automatically increases heart rate and blood pressure, thereby improving blood supply to the muscles, triggering the release of hormones that optimize energy supply to the muscles, focusing concentration on the potential threat, and diverting thoughts away from other, currently unimportant things. All of this creates the ideal conditions for two courses of action: fight or flight.

An emotion is therefore something very far-reaching and comprehensive. It focuses our attention and influences our thinking and our self-assessment – that is, our cognitive processes. It is reflected in bodily functions such as heart rate, blood pressure, and sweating, which are controlled by the vegetative (=autonomous) nervous system and hormones – the physiological component of emotion.

Finally, an emotion inevitably finds its way to the outside world in facial expressions, gestures, tone of voice, and behavioral tendencies – these are the expressive and behavioral components. This aspect is already inherent in the term itself: “emotion” comes from the Latin words ‘ex’ and “movere” and means movement outward. The subjective component, i.e., the conscious feeling, often only becomes clear to us in retrospect – if at all.

A difficult subject for research

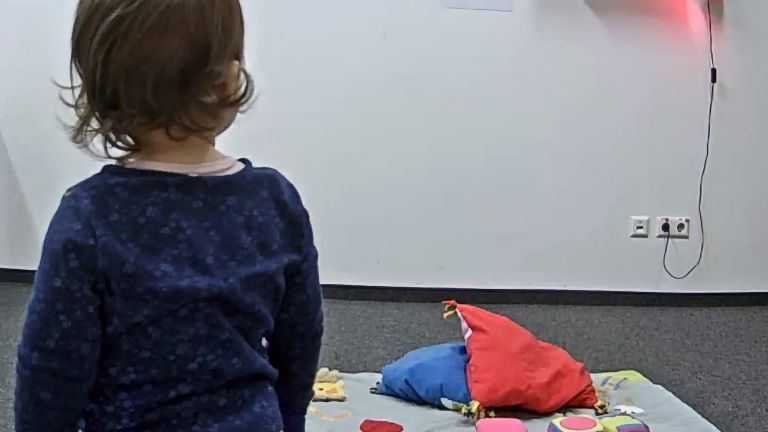

How exactly the individual components are connected, what comes first in emotional processes, and what causes what and how has been a subject of scientific inquiry for over a century ▸ On the trail of emotions. Fear is the most intensively studied and best understood emotion. We know quite a bit about the areas of the brain involved in this very powerful emotion and the neurobiological processes behind it, mainly from animal experiments. However, there is one major catch: mice and rats cannot communicate their subjective feelings.

In general, emotions are difficult for researchers to grasp, as they are complex and multifaceted. Controlling them is problematic, as not everyone reacts the same way to certain situations. They are also difficult to measure – even those affected often experience their emotions only ambiguously and can only describe them in vague terms. This is especially true when the feelings are not caused by clear and striking experiences such as unfair treatment, the sight of suffering, or the reunion with a loved one after a long separation.

Emotions bring color to life

Scientists themselves struggle with the basic terminology. The two emotion researchers James Russell and Ernst Fehr summed this up in a much-quoted sentence: “Everyone knows what an emotion is until they are asked to define it.” There is debate as to whether, as with tastes, there are a certain number of basic emotions from which all others can be composed ▸ The roots of feelings. There is disagreement as to how exactly motivations and emotions are related and how they can be distinguished from one another. At least there is consensus on the difference between emotions and moods: emotions are comparatively short-lived reactions to an external or mental stimulus, while moods are more long-lasting, less pronounced states, often without a recognizable trigger.

Despite all the difficulties in defining them, one thing is clear: emotions bring color to our lives. The colors are not always beautiful and harmonious, but if you try to imagine life without them, strictly objective and rational, without feeling and compassion, human existence would be eerily gray, empty, and meaningless. Much of what makes us unique as individuals and our life stories would also be lost. Individual emotionality is a crucial part of our personality. And it is precisely the episodes in our past that are accompanied by strong emotions that have shaped us and define our identity. Personal experience alone shows that we remember our first love better and more vividly than the geography we learned in 10th grade. And science can now confirm that emotional events are particularly deeply engraved in our memory.

Nevertheless, emotions often have a bad reputation. They are said to cloud rational judgment, and make decisions irrational and people unpredictable - and not only by rational people. It is undeniable that a heated argument, for example, often does little to solve a problem, or that the exam anxiety described at the beginning can prevent us from applying what we have learned. On the other hand, emotions have developed over the course of evolution for a reason. They are essential for making decisions and responding appropriately to our environment. Or, as António Damásio, a neuroscientist at the University of Southern California and arguably one of the most renowned minds in his field, puts it: “Emotions are not a luxury, but a complex tool in the struggle for existence.”

Lightning-fast evaluation systems

Evolution has produced emotions so that we do things that are essential for survival and pass on our genes to the next generation. To ensure this, emotionally driven behavior is associated with pleasant or unpleasant feelings. Startle responses, such as jumping back onto the sidewalk when a car horn suddenly sounds next to us, can save lives. The same is true of disgust, an emotion that has only recently attracted scientific interest, but which has been preventing humans from touching or eating potentially pathogenic things for thousands of years. ▸ Researching disgust

Pleasure and joy motivate us, showing us what is worth investing our energy and time in. People who have suffered damage to parts of the cortex that are important for processing emotions, on the other hand, face almost insurmountable problems when standing in front of their wardrobe in the morning. After all, how can you decide completely emotionlessly whether to wear the striped or the polka-dot tie?

Emotions are therefore a powerful system for evaluating situations and initiating actions. And they are fast: the emotional reaction often occurs before we are even aware of the issue, let alone have thought about it. This is because emotional circuits in the limbic system can make an initial assessment and prepare the appropriate behavior – even before the comparatively slow-working higher areas of the cortex, where conscious feelings arise, become involved.

An important tool for communication

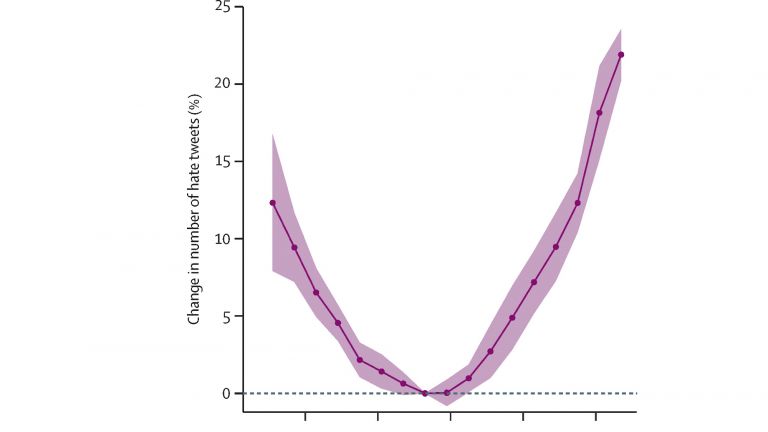

Finally, emotions also play a central role in social interaction. Much of our communication, albeit often unconsciously, takes place through the transmission of emotions via their expressive components – things like facial expressions, gestures, body language, and tone of voice. This allows us to tune in to someone before they have had time to put their concerns into words, or to quickly perceive where important things are happening in large crowds, where it is worth participating, or where danger may be lurking.

The importance of this social, communicative component is clearly illustrated by autism. People with this developmental disorder are, in a sense, illiterate when it comes to recognizing nonverbal communication of emotions. Because they cannot understand the emotional expressions of others, they tend to live a life that is largely withdrawn from their environment. And that is just one of many emotional disorders that fundamentally impair social, private, and professional life.

Recommended articles

When emotions run wild ...

Another case of emotional experience getting out of control is depression – not a temporary sad mood, but a serious illness that, according to estimates by the World Health Organization, affects one in ten people at some point in their lives. This impairs reactions to joyful events or the positive emotions of others. The mood spectrum is narrowed, motivation is lacking, and concentration is difficult. In severe forms of depression, even complete numbness and inner emptiness set in: the person affected has turned away from their environment and revolves around themselves, caught in a negative cycle of brooding about their own misery and a hopeless future.

In post-traumatic stress disorder, patients suffer from extremely emotional events (traumas) that are particularly deeply engraved in their memory. As a result, those affected relive them again and again later on – including in the form of nightmares. The consequences can include insomnia, tantrums, or emotional impoverishment. Another example of impaired emotional experience is anxiety disorder, in which the fear circuit is activated by the most everyday situations, so that the flight and avoidance impulses that are actually useful for survival effectively prevent a normal life.

A complicated matter – from a neuroscientific point of view, as well

The beautiful and normal examples, as well as the possible disorders, show that emotions are not simply another element alongside mental, physical, and social processes. Rather, emotions permeate all of these areas and interact with them. From decision-making processes to interpersonal interaction to questions of health and well-being – nothing can be satisfactorily explained without them.

Because they are difficult to grasp, science has long paid little attention to emotions. However, this changed in the 1990s, not least due to the development of imaging techniques such as functional magnetic resonance imaging. Since then, brain researchers in the field of affective neuroscience have also been investigating the associated processes in the brain, and have thus contributed greatly to our understanding of fear and happiness in particular. However, the assumption that has existed since the 1930s that there is a defined neural system responsible for processing all emotions does not seem to be confirmed. Although there are areas such as the limbic system that play a key role in emotional processes, these also perform completely different tasks. Conversely, emotional stimuli activate brain regions such as the hippocampus, which is primarily responsible for memory. ▸ The circuitry of fear. What we know from our own experience also applies in neuroscience: emotions are a complicated matter.

Further reading

- Languages of Emotion. Cluster of Excellence at Freie Universität Berlin; URL: http://www.languages-of-emotion.de/ [as of July 17, 2018]; website.

First published on August 23, 2011

Last updated on September 11, 2025