The Fear Circuit

The sight of a spider or a shadow darting across the dark triggers the brain's sensitive alarm system in a flash, resulting in sweating and sheer terror. Often, it is a false alarm. But the brain quickly corrects itself.

Wissenschaftliche Betreuung: Prof. Dr. Alfons Hamm

Veröffentlicht: 11.09.2025

Niveau: mittel

- Die Amygdala schätzt Gefahren ein und steuert die Kaskade der Angstreaktionen.

- Direkt vom Thalamus erhält die Amygdala eine grobe Skizze der Situation, um schnell die Gefahr einzuschätzen.

- Eine genaue Analyse liefert etwas später der langsamere Weg vom Thalamus über den Neocortex und den Hippocampus.

Amygdala

Amygdala/Corpus amygdaloideum/amygdala

Ein wichtiges Kerngebiet im Temporallappen, welches mit Emotionen in Verbindung gebracht wird: es bewertet den emotionalen Gehalt einer Situation und reagiert besonders auf Bedrohung. In diesem Zusammenhang wird sie auch durch Schmerzreize aktiviert und spielt eine wichtige Rolle in der emotionalen Bewertung sensorischer Reize. Darüber hinaus ist sie an der Verknüpfung von Emotionen mit Erinnerungen, der emotionalen Lernfähigkeit sowie an sozialem Verhalten beteiligt. Die Amygdala – zu Deutsch Mandelkern – wird zum limbischen System gezählt.

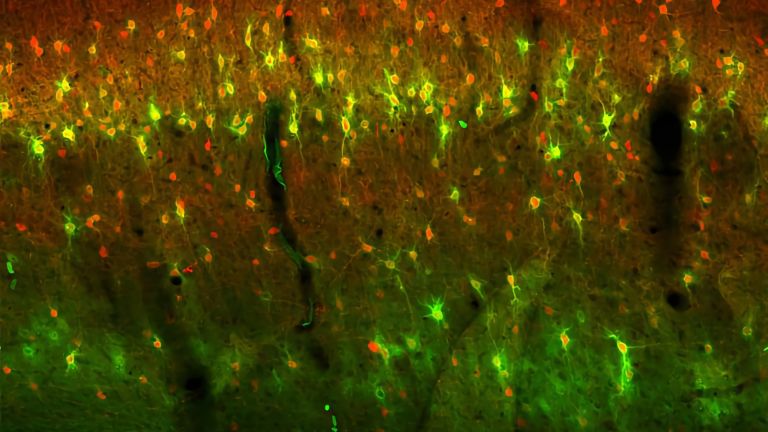

„Ist Emotion ein magisches Produkt“, fragte 1937 der Neuroanatom James Papez (1883–1958) „oder ist es ein physiologischer Prozess, der von einem anatomischen Mechanismus abhängt?“ Papez entschied sich für die zweite Antwort. Er glaubte, dass Emotion ein Produkt des limbischen Systems wäre, das der Mediziner Paul Broca (1824–1880) schon 1878 als „grand lobe limbique“ beschrieben hatte. Dieses stammesgeschichtlich uralte Areal besteht aus mehreren verbundenen Strukturen, unter anderem der Amygdala, dem Hippocampus und dem Septum. Über die Frage, welche Strukturen genau zum limbischen System zählen, und ob man überhaupt von einem „System“ sprechen könne, streiten sich die Anatomen jedoch noch heute. Denn einige der Bestandteile des limbischen Lappens spielen zwar eine Rolle bei Gefühlen und sexuellem Verhalten, andere sind jedoch für das Gedächtnis oder die Motivation und Navigation zuständig.

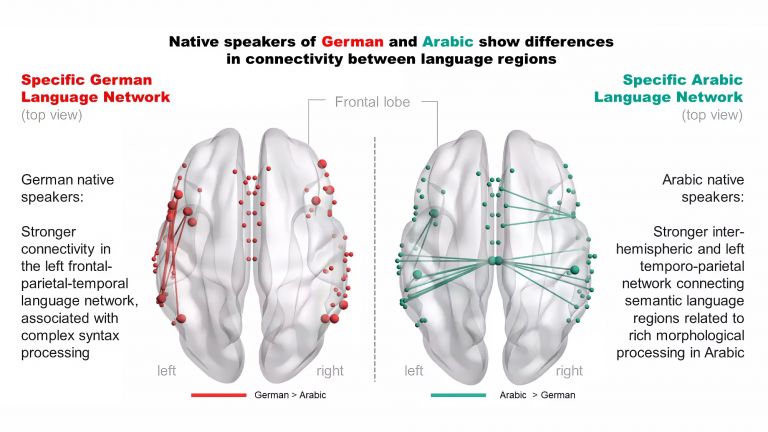

Die Annahme, dass Emotion und Rationalität im Gehirn räumlich getrennt liegen, ist unter Laien weit verbreitet. In der rechten Hemisphäre, glauben viele, sitzen die Emotionen, in der linken die Vernunft. Tatsächlich scheint die rechte Hirnhälfte für die Emotionsverarbeitung besonders wichtig zu sein. Nach rechtsseitigen Gehirnverletzungen fällt es Patienten schwerer, Gefühle im Gesicht des anderen zu deuten. Doch auch linkshemisphärische Verletzungen wirken sich auf die Gefühlswelt aus: Häufig leiden Patienten unter einer so genannten Katastrophenreaktion mit tiefer Depression. Dies legt nahe, dass die linke Hemisphäre unsere Gefühlslage aufhellt, indem sie die rechte Hemisphäre hemmt. Studien mit Neugeborenen sprechen ebenfalls dafür, dass die linke Hemisphäre stärker bei positiven, die rechte mehr bei negativen Gefühlen aktiv ist.

Neurowissenschaftler warnen jedoch davor, komplexe Phänomene wie Emotionen einer einzigen Hirnhälfte zuzuordnen. Denn an nahezu allen Funktionen sind grundsätzlich beide Hemisphären beteiligt – wenn auch in unterschiedlichem Ausmaß. Bei Split-Brain-Patienten, deren neuronale Verbindung zwischen beiden Hemisphären gekappt ist, lassen sich die relativen Stärken der beiden Hirnhälften gut beobachten: Die linke Hemisphäre ist demnach besser darin, nach Ursachen und Erklärungen zu suchen. Dagegen besitzt die rechte Hemisphäre ein besonderes Talent für räumlich-visuelle Aufgaben.

Depression

Depression/-/depression

Psychische Erkrankung, deren Hauptsymptome die traurige Verstimmung sowie der Verlust von Freude, Antrieb und Interesse sind. In den gegenwärtigen Klassifikationssystemen werden verschiedene Arten der Depression unterschieden.

Die hormonellen und vegetativen Reaktionen auf das Gefühl der Angst und die automatisch ablaufenden Verhaltensprogramme in Folge dienen dazu, das Überleben zu sichern. Indem die Hypophyse Stresshormone ausschüttet, ermöglicht sie dem Bedrohten, schneller und effizienter zu handeln. Das basale Vorderhirn steigert zusätzlich die Aufmerksamkeit und Erregung. Über den Hirnstamm wird das autonome System aktiviert: Der Blutdruck und die Frequenz des Atems und Herzschlags steigen, die Muskeln ziehen sich zusammen – der Geängstigte ist bereit für die Flucht oder den Kampf. Damit Verletzungen den Menschen oder das Tier nicht ablenken, senkt der Hirnstamm auch die Schmerzwahrnehmung. Schließlich sorgt der Hirnstamm auch noch für automatisierte Verhaltensprogramme, wie den Gesichtsausdruck der Angst oder Angstschreie, um Artgenossen zu Hilfe zu rufen.

Aufmerksamkeit

Aufmerksamkeit/-/attention

Aufmerksamkeit dient uns als Werkzeug, innere und äußere Reize bewusst wahrzunehmen. Dies gelingt uns, indem wir unsere mentalen Ressourcen auf eine begrenzte Anzahl von Reizen bzw. Informationen konzentrieren. Während manche Stimuli automatisch unsere Aufmerksamkeit auf sich ziehen, können wir andere kontrolliert auswählen. Unbewusst verarbeitet das Gehirn immer auch Reize, die gerade nicht im Zentrum unserer Aufmerksamkeit stehen.

“It was just before midnight,” reports 48-year-old Martha Kristensen, "my husband and I were standing in front of our hotel in Naples. Suddenly, someone kicked me in the back of the knee from behind, threw me to the ground, and grabbed me and my backpack. I was terrified that they would kidnap me and drag me into a car. My heart was racing, I was frozen with fear. It happened so fast that I couldn't even scream for help."

Source of emotions

Fear: a feeling that everyone knows, even if they have been spared terrible experiences like that of architect Martha Kristensen (name changed by the editors). We are afraid of heights, plane crashes, dogs, our boss. When we feel this emotion, we feel it from the tips of our toes to the top of our heads. Our heart beats faster, our hands tremble, we sweat, our stomach rumbles.

Scientists have long been interested in the structures in the brain that cause us to freeze in fear or anxiety. Numerous studies on animals and humans have been conducted over the past decades to answer this question. And so it comes as no surprise that the mechanisms of fear are now among the most thoroughly researched circuits of our emotional apparatus.

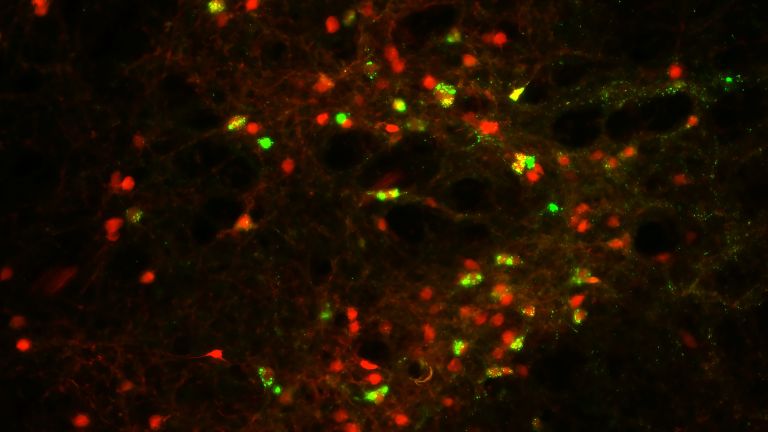

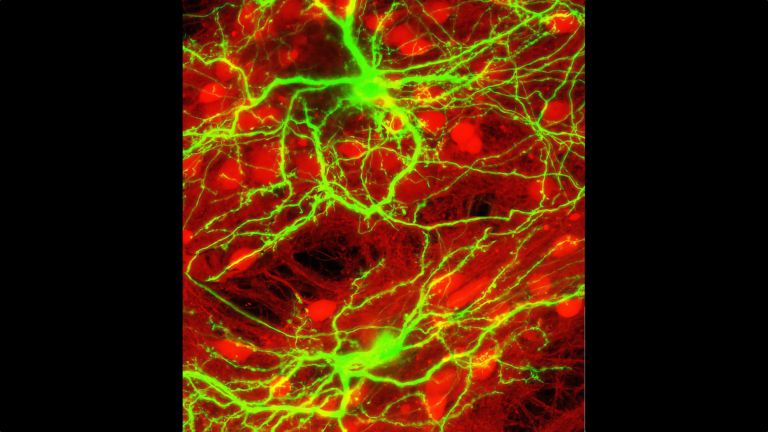

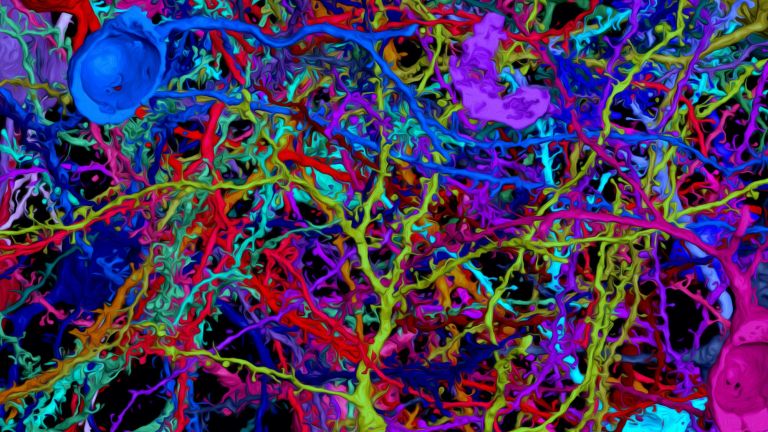

It is now proven that one structure in particular plays a major role in this process: the amygdala (almond kernel). It is part of the limbic system, which is believed to play an important role in emotion processing (see info box). The amygdala also plays a central role in aggression. It consists of two almond-shaped clusters of nerve cell bodies located in the center of the human brain, one in the left and one in the right temporal lobe, directly in front of the hippocampus.

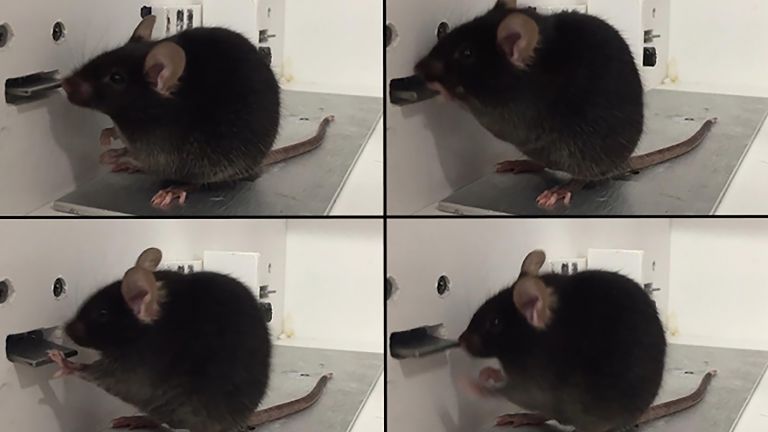

Even the smallest injuries to the structures of the amygdala are enough to completely change an animal's behavior: “Wild-caught birds,” reported biologist Richard Phillips of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute, “which normally try to escape in panic, suddenly become completely calm.” Laboratory rats with a lesion of the amygdala curiously explore sedated cats. Conversely, electrical stimulation of small cell clusters in the amygdala is enough to make cats cower fearfully from mice or react angrily with raised fur, hunched backs, and dilated pupils – depending on which area of the amygdala was stimulated.

Innate and learned fears

The amygdala thus serves as an alarm system for animals and humans. Within a few milliseconds, it evaluates situations and assesses dangers. Some sights, sounds, or smells trigger fear from birth or after a single encounter. For example, laboratory rats that have never lived in the wild are afraid when they hear the cry of an owl or smell a predator.

Some fears are not innate, but very easy to acquire. Monkeys, for example, fear snakes as soon as they observe another monkey reacting with fear to a reptile. The amygdala of primates reacts similarly sensitively to negative facial expressions of others. Evolutionarily, such innate fears or tendencies toward fear are of great advantage to the individual creature: for example, if a rat quickly flees when it hears an owl hooting, it may save its life.

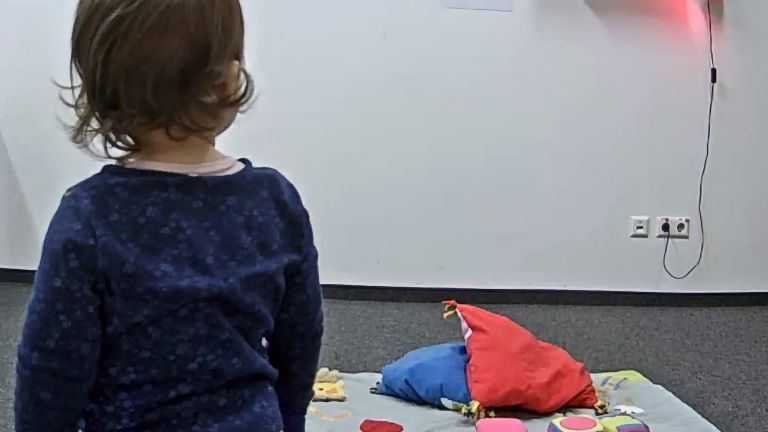

However, even stimuli that have long been perceived as neutral or positive can become associated with danger through learning processes and later trigger fear themselves. If a neutral stimulus occurs simultaneously or shortly before an unpleasant stimulus such as pain, the fear triggered by the unpleasant stimulus rubs off on the neutral stimulus. The sounds Martha Kristensen heard immediately before she was kicked in the back of the knee were stored by her amygdala as threatening. “When I hear footsteps behind me today,” she says, “especially at night, I still feel afraid. I turn around or walk faster.”

Empfohlene Artikel

Circuitry of fear

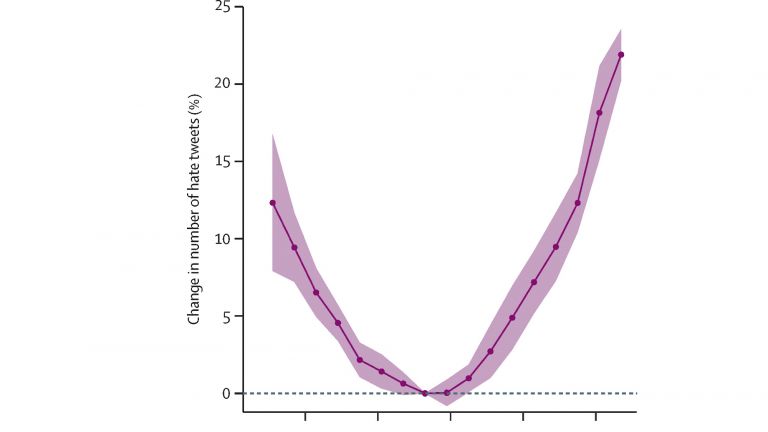

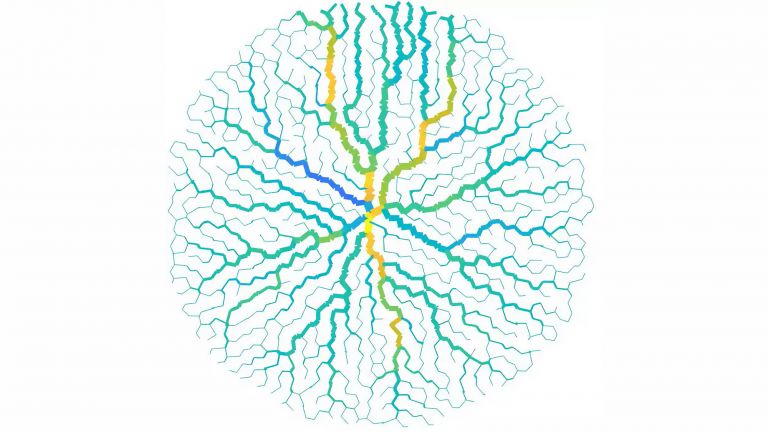

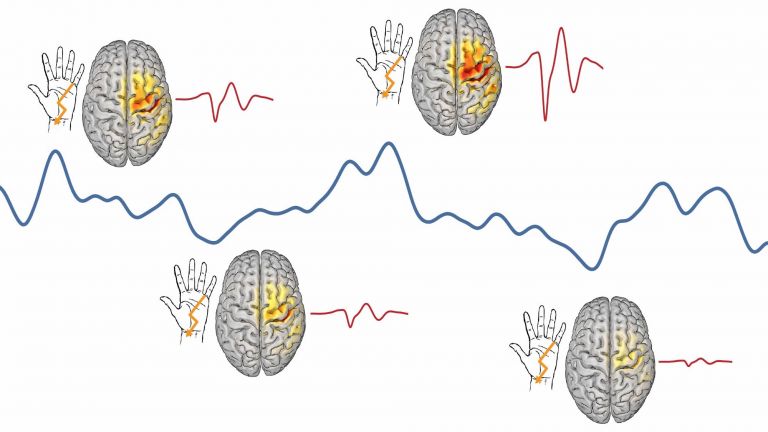

But how does the brain actually know whether a situation is dangerous? Neuroscientist Joseph LeDoux of New York University has described the underlying mechanisms as a fear circuit that sends information to the amygdala in two ways: one fast, rough, and error-prone, and one slow but verified by precise analysis.

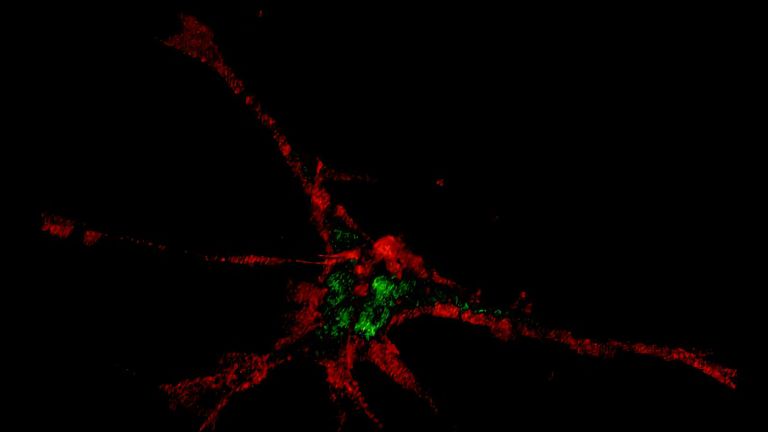

The starting point is always the thalamus. This part of the diencephalon forms the gateway to consciousness and is an important central hub for messages from the sensory organs. When it receives an emotional stimulus, such as a loud noise, it forwards a rough sketch of the sensory impression directly to a small group of cells (“fear-on” neurons) in the lateral amygdala.

When these cell clusters are activated, the information flows on to the central core of the amygdala. This is where the defensive behavior programs are activated. This triggers physical fear responses, as Martha Kristensen describes: “Everything happened so fast, I was afraid, my heart was racing, I was frozen with fear. I only felt the many bruises afterwards.” Thanks to this thalamo-amygdala connection, animals and humans can react to danger at lightning speed (see info box).

The brain stem and cerebral cortex are also informed. The brain stem triggers automatic behavioral responses, which can range from freezing to fleeing to attacking. The cerebral cortex is responsible for the emotional experience of fear.

False alarms and their correction

However, this sensitive, rapid pathway of the fear circuit occasionally triggers false alarms: for example, when we are startled by our own shadow, the sound of a whistle, or the sight of a snake-shaped stick. In addition to the shortcut described by LeDoux as “quick and dirty,” there is also the so-called “high road” of cognitive processing leading from the thalamus to the amygdala.

On this conscious route, sensory information from the thalamus first reaches the cortex and the hippocampus. There, the impressions are analyzed in more detail before they reach the amygdala. The sensory areas of the neocortex enable us to perceive fear stimuli in a more differentiated way and, for example, to distinguish a woman's tiptoeing steps from a man's heavy footsteps. However, the brain needs time to do this: it takes twice as long for the information to reach the amygdala via the cortex as it does via the direct route from the thalamus.

In addition, the hippocampus also brings conscious memories of unpleasant or anxiety-provoking situations into play via the slow route. When Martha Kristensen hears footsteps close behind her, for example, she sees images of the attack in Naples again. LeDoux describes it this way: " The hippocampus is crucial in recognizing a face as that of your cousin. But it is the amygdala that adds that you don’t really like him!"

Just like the neocortex, the hippocampus is also connected to the amygdala. It can curb fear by analyzing characteristics with more nuance and assessing a stimulus as harmless. This is why we sometimes get scared of our own shadow – and then, just a split second later, breathe a sigh of relief and laugh because we realize it was a false alarm.

First published on August 15, 2012

Last updated on September 11, 2025