Reason vs. emotion?

Humans are not machines; emotions control many of our actions. However, reason also has a say. If you want to make complex decisions, you should rely on your intuitive knowledge based on experience.

Wissenschaftliche Betreuung: Prof. Dr. Alfons Hamm

Veröffentlicht: 11.09.2025

Niveau: mittel

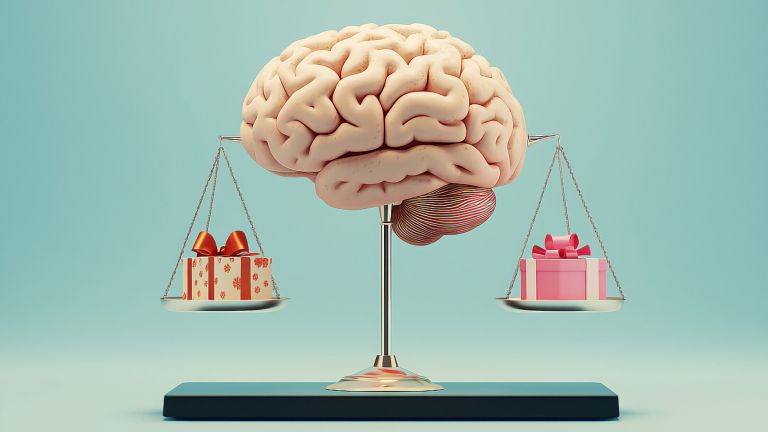

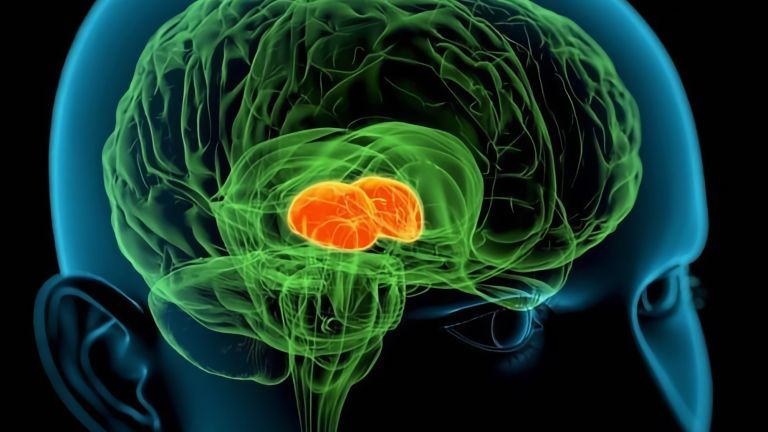

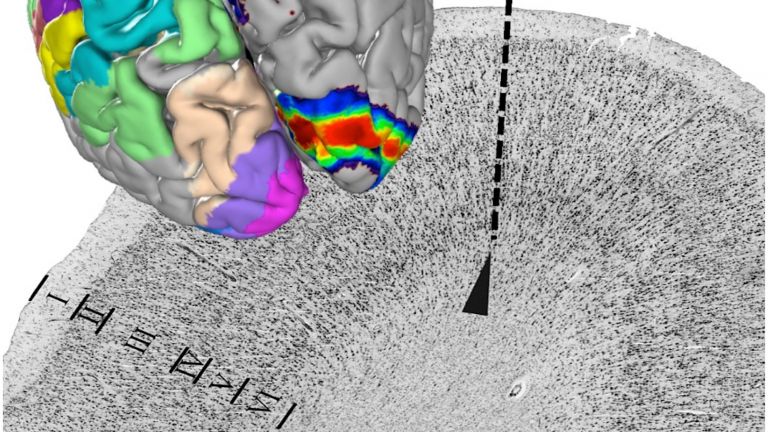

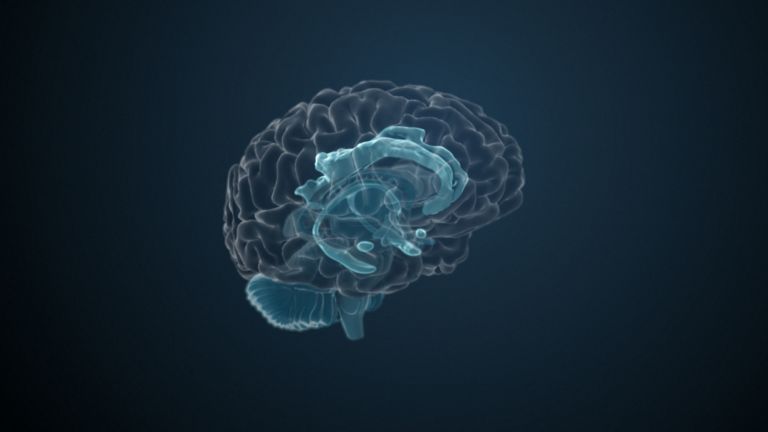

- Im limbischen System sind unsere Emotionen verankert, dort entstehen auch Affekte; im präfrontalen Cortex sitzt unser Verstand, der rational Vor- und Nachteile abwägt und unsere Handlungen in der Zukunft plant.

- Zwar kann der Verstand die Gefühle in gewissem Maße kontrollieren, in der Realität steuern aber meist Gefühle das Handeln, auch wenn dem Menschen dies gar nicht bewusst wird. Das alltägliche Leben lässt sich zudem oft mit einfachen Faustregeln meistern.

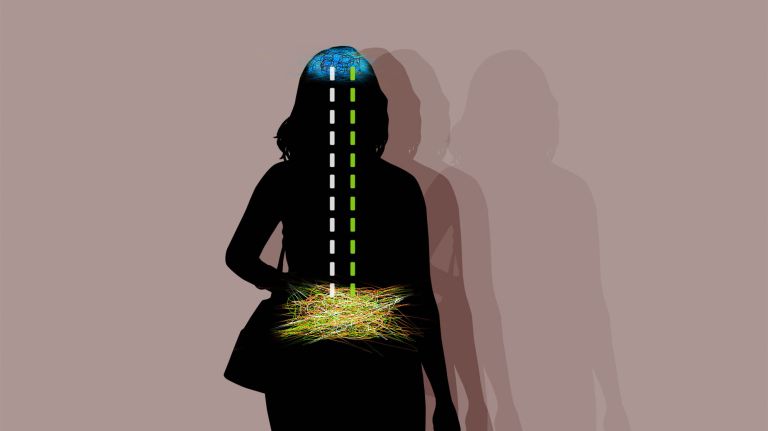

- Hirnforscher unterscheiden das rein spontane Bauchgefühl von der Intuition, die Erfahrungswissen aufarbeitet, welches über Jahre hinweg gespeichert wurde.

- Studien zeigen: Komplexe Entscheidungen, die viele Faktoren berücksichtigen müssen, überfordern das Arbeitsgedächtnis. Hier sollte man – wenn möglich – der Intuition vertrauen.

Cortex

Großhirnrinde/Cortex cerebri/cerebral cortex

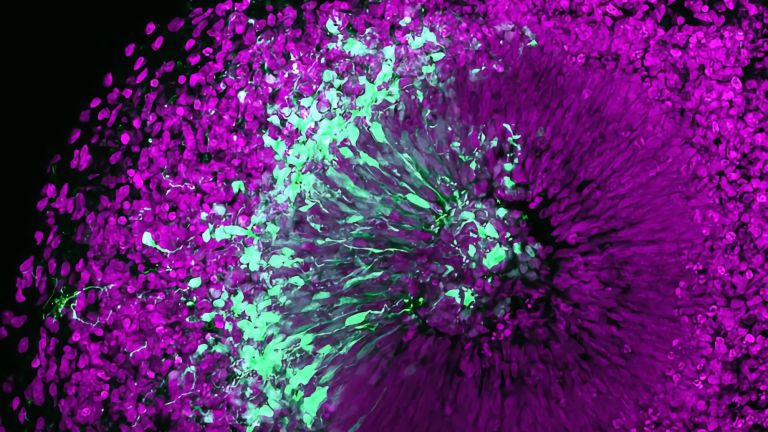

Cortex bezeichnet eine Ansammlung von Neuronen, typischerweise in Form einer dünnen Oberfläche. Meist ist allerdings der Cortex cerebri gemeint, die äußerste Schicht des Großhirns. Sie ist 2,5 mm bis 5 mm dick und reich an Nervenzellen. Die Großhirnrinde ist stark gefaltet, vergleichbar einem Taschentuch in einem Becher. So entstehen zahlreiche Windungen (Gyri), Spalten (Fissurae) und Furchen (Sulci). Ausgefaltet beträgt die Oberfläche des Cortex ca 1.800 cm2.

Arbeitsgedächtnis

Arbeitsgedächtnis/-/working memory

Eine Form des Gedächtnisses, häufig synonym mit dem Begriff "Kurzzeitgedächtnis" genutzt. Viele Theoretiker unterscheiden beide Konzepte jedoch klar, mit Hinblick auf die Manipulation von Informationen im Arbeitsgedächtnis. Es hält Informationen zeitweise aufrecht, beinhaltet gerade aufgenommene Informationen und Gedächtnisinhalte aus dem Langzeitgedächtnis, die mit den neuen Informationen in Verbindung gebracht werden. Im Modell von Alan Baddeley und Graham Hitch beinhaltet es eine zentrale Exekutive, eine phonologische Schleife, einen episodischen Puffer und ein visuell-räumliches Notizbuch.

Der portugiesische Neurowissenschaftler António Damásio von der University of Southern California sieht so genannte somatische Marker – quasi Körpersignale – als Grundlage aller menschlichen Entscheidungen an. Im präfrontalen Cortex ist auch die Fähigkeit beheimatet, Körperempfindungen wahrzunehmen – und diese somatischen Marker helfen laut Damásio beim Denken, indem sie Vorentscheidungen treffen und uns, ohne dass es uns bewusst würde, in eine bestimmte Richtung drängen.

Cortex

Großhirnrinde/Cortex cerebri/cerebral cortex

Cortex bezeichnet eine Ansammlung von Neuronen, typischerweise in Form einer dünnen Oberfläche. Meist ist allerdings der Cortex cerebri gemeint, die äußerste Schicht des Großhirns. Sie ist 2,5 mm bis 5 mm dick und reich an Nervenzellen. Die Großhirnrinde ist stark gefaltet, vergleichbar einem Taschentuch in einem Becher. So entstehen zahlreiche Windungen (Gyri), Spalten (Fissurae) und Furchen (Sulci). Ausgefaltet beträgt die Oberfläche des Cortex ca 1.800 cm2.

Bei Entscheidungen, die sehr viele verschiedene Faktoren einbeziehen, ist nachweislich das Arbeitsgedächtnis im präfrontalen Cortex überfordert. In einer Studie des niederländischen Sozialwissenschaftlers Ap Dijksterhuis von der Radboud University Nijmegen aus dem Jahr 2006 mussten Probanden das beste Auto unter vielen aussuchen. Gab es nur vier Kategorien, die mit in die Entscheidung hineinspielten – solche Kategorien waren etwa Benzinverbrauch, Leistung oder Stauraum – dann trafen die Probanden eine qualitativ bessere Entscheidung, wenn sie in Ruhe darüber nachdenken konnten. Galt es aber zwölf Faktoren mit einzubeziehen, entschieden sich die Probanden besser, wenn sie während des Nachdenkens abgelenkt waren und daher eher intuitiv entschieden.

Arbeitsgedächtnis

Arbeitsgedächtnis/-/working memory

Eine Form des Gedächtnisses, häufig synonym mit dem Begriff "Kurzzeitgedächtnis" genutzt. Viele Theoretiker unterscheiden beide Konzepte jedoch klar, mit Hinblick auf die Manipulation von Informationen im Arbeitsgedächtnis. Es hält Informationen zeitweise aufrecht, beinhaltet gerade aufgenommene Informationen und Gedächtnisinhalte aus dem Langzeitgedächtnis, die mit den neuen Informationen in Verbindung gebracht werden. Im Modell von Alan Baddeley und Graham Hitch beinhaltet es eine zentrale Exekutive, eine phonologische Schleife, einen episodischen Puffer und ein visuell-räumliches Notizbuch.

Cortex

Großhirnrinde/Cortex cerebri/cerebral cortex

Cortex bezeichnet eine Ansammlung von Neuronen, typischerweise in Form einer dünnen Oberfläche. Meist ist allerdings der Cortex cerebri gemeint, die äußerste Schicht des Großhirns. Sie ist 2,5 mm bis 5 mm dick und reich an Nervenzellen. Die Großhirnrinde ist stark gefaltet, vergleichbar einem Taschentuch in einem Becher. So entstehen zahlreiche Windungen (Gyri), Spalten (Fissurae) und Furchen (Sulci). Ausgefaltet beträgt die Oberfläche des Cortex ca 1.800 cm2.

“The heart has its reasons, which reason knows nothing of,” wrote the French mathematician and philosopher Blaise Pascal (1623-1662). And indeed, many of the decisions that humans make cannot be explained or understood by reason – usually not even by the person who made them. Did the head decide, the gut, or something else entirely?

Reason resides in the frontal lobe

When a person thinks rationally about a problem, weighs up the pros and cons, or plans their future, they use the prefrontal cortex. This area of the brain is connected to the limbic system, the seat of emotions, and can control emotions – when it is reasonable to do so. The economic model of Homo economicus is based on the idea that every consumer thinks through the costs and benefits of their decisions purely rationally, and soberly attempts to maximize their profit. So, are humans purely rational beings controlled by their frontal lobe?

This model is now outdated: economists have simply overestimated the influence of rational decisions. No one acts purely rationally. Psychologist Gerd Gigerenzer from the Max Planck Institute for Human Development in Berlin puts it this way: “People make decisions – and now I'm going to say something radical, especially for us economists – mostly without calculating benefits and probabilities.”

For example, someone who blurts out “I quit!” to their boss in the heat of the moment has allowed themselves to be overwhelmed by their strong emotions. These emotions actually come, as the colloquial expression goes, partly from the gut (see info box). Such spontaneous emotional outbursts occur before one can properly identify the trigger (e.g., frustration with the boss) and the feeling. In fact, a mixture of feelings such as anger, guilt, disappointment, and sadness arise later.

Fear of loss

A core area of the limbic system, the amygdala, fires especially when fear is involved, such as when there is a risk of losing something. In a study, Benedetto De Martino and his colleagues at University College London used magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to look into the brains of test subjects who were offered £50 and given a choice: if they opted out at the beginning of the game, they would receive £20; if they continued playing, they could either win the entire £50 or walk away empty-handed. The interesting thing was that the way the question was phrased had a decisive influence on the subjects' decision. 62 percent chose to take the risk when they were told, “You will lose £30 if you don't play.” When told, “You can keep £20,” only 43 percent risked their luck.

Scientists refer to this as the framing effect: when the same fact is phrased differently, people often make different decisions. The reason: the threat of losing £30 activates the amygdala and motivates people to take the risk – after all, otherwise they will lose something. However, the amygdala does not fire when it comes to the prospect of earning £20 for sure – even though the result for the wallet is exactly the same.

In addition to the amygdala, the reward system in the brain is also an early indicator of decisions. This includes, among other things, the nucleus accumbens. In an experiment, Brian Knutson of Stanford University offered his subjects chocolates for actual purchase in an MRI scanner. When the subjects reached for the chocolates, the nucleus accumbens was stimulated even before the subjects were aware that they were consenting. If the treat was too expensive, however, the insular cortex fired, obviously vetoing the purchase.

Empfohlene Artikel

Emotions are often stronger than reason

Emotions also set the tone when we perceive something as unfair. This was discovered in 2003 by a team led by Alan Sanfey, now at the Donders Institute for Brain, Cognition and Behavior at Radboud University Nijmegen. A player received a sum of money and had to decide how much of it to give to his fellow player. Only if the other player also accepted could both keep the money. If the person weighed up the situation purely rationally using the prefrontal cortex, the other player would always accept, because then they would ultimately receive money; if they refused, they would receive nothing at all.

However, many test subjects indignantly rejected unfair offers. This stimulated the insular cortex, cingulate gyrus, and prefrontal cortex in the brain. The researchers interpreted this as emotional conflict: the prefrontal cortex fired to overcome the negative feelings from the other two areas of the brain and persuade the test subjects to accept the unfair offer anyway. The prefrontal cortex therefore attempts to control and override emotions, but this does not always work.

The late brain researcher Gerhard Roth from the University of Bremen puts it even more radically: it is not reason that primarily guides our actions, but rather affects and emotions. This often happens unconsciously. “And so it happens that when asked, ‘Why did you just make that decision?’, we make something up because we simply have no access to our unconscious motives and impulses.” However, this does not mean that the mind cannot counteract this, said Roth. This tends to happen indirectly: the mind is only able to influence our plans for action by coupling opposing feelings. For example, if you feel like having chocolate spread for breakfast in the morning, even though you actually want to lose weight, reason can ensure that you leave the fatty food alone. According to Gerhard Roth, there are no rational decisions, only rational considerations.

Trust your intuition

But it's not always feelings that guide us, says psychologist Gerd Gigerenzer: Many “gut decisions” are often based on simple rules of thumb and experience that greatly simplify life. As an example, he cites the attempt to catch a ball: No one would calculate the ball's point of impact based on its trajectory, air resistance, wind direction, and so on. Instead, you fix your eyes on the ball and try to keep your angle of vision constant while running. This automatically reveals the position at which the ball must be caught. Even preschoolers have this “empirical knowledge” (intuitive physics), as they can effortlessly catch a ball rolling down an inclined plane without being able to explain why the ball must land exactly where they put their hand. But even buying the same brand of cat food every time, or deciding to follow the advice of close friends, is based on such experiential knowledge.

We are often not really aware of this experiential knowledge “because it is stored in a different data format, so to speak,” as Gerhard Roth says. However, it can be activated during decision-making, preferably while sleeping, or at least by temporarily switching off the mind: “Then all previous experiences are scanned, and they receive a kind of average assessment. This then manifests itself as a vague feeling, something like: Yes, I should do that,” says Roth. Especially when it comes to complex decisions, this form of intuition seems to be superior to rational consideration (see info box).

Intuition ha

probably saved many a cyclist from falling: When someone suddenly starts to skid on their bike, they intuitively decide to steer in the opposite direction based on their experience – without knowing the laws of physics or thinking through the consequences. However, if you ask people in advance what they would do in such a situation, they usually give completely wrong answers, the implementation of which would inevitably lead to a fall.

First published on February 20, 2012

Last updated on September 11, 2025