Signals from Within

We snort with anger or beam with happiness. Emotions determine our lives and influence our behavior. Emotional signals are therefore also a means of communication.

Wissenschaftliche Betreuung: Prof. Dr. Dirk Wildgruber

Veröffentlicht: 18.12.2025

Niveau: mittel

- Menschen sind sehr gut darin, die Emotionen anderer anhand von Mimik und Stimmlage zu erkennen. Basisemotionen wie Ärger, Trauer oder Freude lösen bei allen Menschen ein ähnliches Mienenspiel aus.

- Emotionen anderer geben wichtige soziale Hinweise. So deutet ein trauriges Gesicht auf Hilfsbedürftigkeit hin, ein ängstlicher Gesichtsausdruck warnt vor Gefahren.

- An der Emotionserkennung sind Hirnareale beteiligt, die auch für die Erzeugung von Emotionen zuständig sind.

Basisemotionen

Basisemotionen/-/basic emotions

Einige Theorien gehen davon aus, dass alle Emotionen sich aus einigen wenigen Basisemotionen zusammensetzen lassen. Diese werden auch als Primäremotionen bezeichnet. Hierzu zählen klassisch nach Ekman Furcht, Wut, Freude, Trauer, Ekel und Überraschung. Primäremotionen treten infolge eines Ereignisses sehr rasch auf und klingen teilweise schnell ab. Im Verlauf können sie in Sekundäremotionen übergehen (z. B. Scham, Schuld oder Stolz).

Wir heulen vor Wut oder sind zu Tränen gerührt. Doch welchen Zweck haben emotionale Tränen? Wissenschaftler meinen, dass Weinen als unmissverständliches Signal dient, um unseren Mitmenschen zu zeigen, dass man unglücklich oder hilflos ist – und Unterstützung brauchen könnte.

Tatsächlich konnten Forscher zeigen, dass Probanden auf Fotos von weinenden Personen deren Gefühlslage schlechter erkennen, wenn die Tränen wegretuschiert sind. Weinen Frauen aus Trauer, senden sie damit auch unsichtbare chemische Signale. Laut einer Studie israelischer Wissenschaftler lässt der nicht wahrnehmbare Geruch von Trauertränen bei Männern den Testosteronspiegel sinken und vermindert auch die sexuelle Erregbarkeit.

Ebenfalls wissenschaftlich bestätigt ist inzwischen das Klischee, dass Frauen näher am Wasser gebaut sind als Männer. Sie weinen bis zu 64 Mal im Jahr, Männer im gleichen Zeitraum höchstens 17 Mal. Der Unterschied entwickelt sich aber erst im Teenager-Alter: Denn Frauen weinen nicht nur öfter, sondern auch länger und aus anderen Gründen als Männer, etwa, wenn sie vor Konflikten stehen. Forscher vermuten darum, dass die Art und die Häufigkeit des Weinens Erwachsener auch kulturell bedingt sein könnten.

Many philosophers have defined humans by their capacity for reason. Aristotle (384–322 BC) spoke of the zoon logicon, the rational animal. However, brain researchers and cognitive psychologists today take a different view from the great Greek thinker: the power that significantly determines us is not reason; it is emotions.

We are under their influence around the clock, day in and day out. Permanently generated by the brain as reactions to the constant stream of information, emotions guide our thoughts and actions. Since only a small part of them is experienced as conscious feelings, we often do not recognize what is driving us at any given moment. And often others recognize our current emotional state better than we do ourselves. Because emotions play such a fundamental role in people's lives, humans have developed a very fine sense of what others are feeling and how they feel about it.

Expressive facial expressions

Emotions are clearly visible on the face. Whether someone frowns or twists the corners of their mouth, those around them can usually recognize exactly what emotions lie behind the facial expression. And this is true around the globe: the so-called basic emotions such as fear, sadness, anger, disgust, surprise, or joy are expressed in facial features that are more or less the same in all cultures and among all people around the world. When we are surprised, for example, our eyes widen and our mouth opens slightly. When we feel joy, the corners of our mouth turn upward and so-called laugh lines form around our eyes. ▸ The Roots of Emotions

These facial expressions, which are characteristic of basic emotions, are intuitively understood all over the world. Incidentally, this also applies to tone of voice: whether someone is angry or in a good mood, whether they are threatening or trying to charm us, we can recognize this even in foreign languages – simply by the tone of voice.

What's more, facial expressions and voice can only be influenced to a limited extent by willpower and are therefore difficult to disguise. But why do our emotions come across so clearly and are so easy to read? Because the obvious expression of emotions has important social functions for people living together in groups. For example, a sad or even crying face tells others that you are feeling bad and may need comfort and support (see box “Why do we cry?”).

An angry face warns of possible imminent aggression and urges others to stay out of the way. And anyone who sees an obviously fearful person is on their guard themselves because this indicates an imminent danger.

Empfohlene Artikel

Emotion recognition in the brain

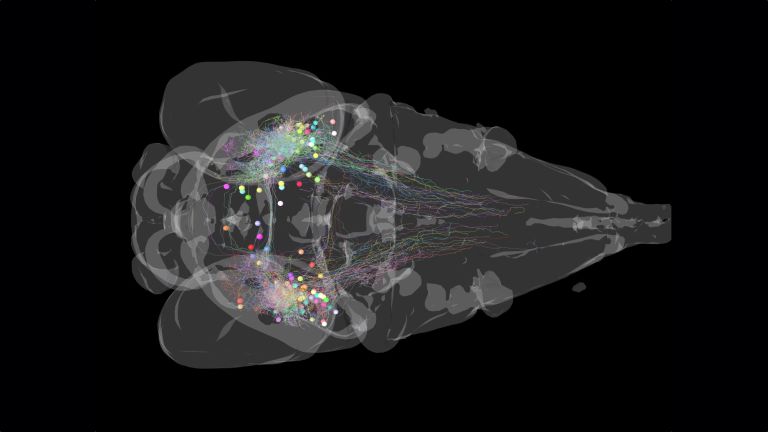

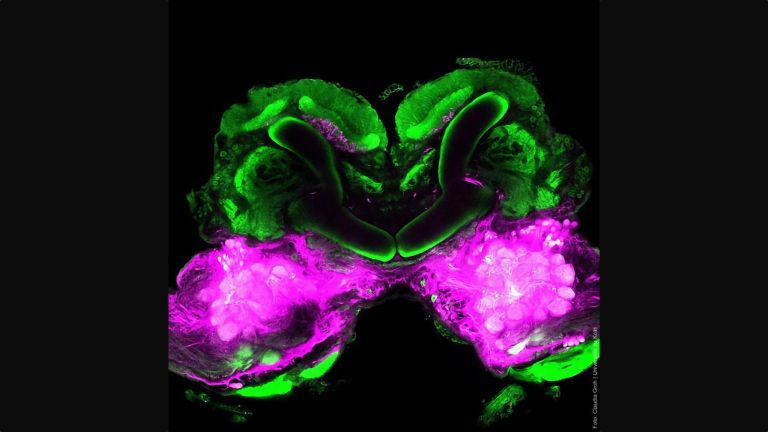

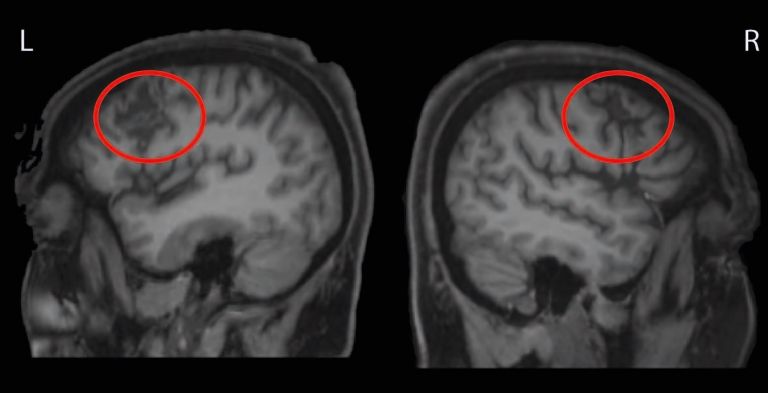

Recognizing the emotions of others happens automatically and at lightning speed. We pay particular attention to the mouth and eyes of the person we are looking at – two areas that are most expressive in facial expressions. When processing this visual information, areas of the brain are active that also play a role in the emergence of emotions. These include parts of the cerebral cortex, the limbic system with the amygdala, and the anterior cingulate cortex, where the so-called spindle cells are particularly active in emotion recognition.

But we don't just read other people's feelings, we also feel them. Mirror neurons in the motor cortex, for example, fire not only when we smile ourselves, but also when we see others smiling. This may be the reason why many emotions are contagious and transfer to others.

A difficult field of research

However, emotions are not an easy area to study in neurobiological research. Because feelings are so fleeting and subjective, they are difficult to measure and evaluate. For this reason, many studies make a strict distinction between emotional experience, which test subjects can only describe through self-assessment, and the expression of emotions, which can also be seen and evaluated by observers. Animal studies are also problematic in the field of affective neuroscience, as animals are known to be unable to provide information about their feelings.

However, some insights have been gained from patients with brain lesions, such as those with deficits in emotion recognition. For example, if the amygdala is damaged, those affected are less able to recognize fear in others. Damage to the insula leads to limitations in recognizing anger. But even people without such defined brain damage sometimes have problems interpreting the feelings of others. Autistic people, for example, have difficulty assigning emotions to faces. Such symptoms also occur in schizophrenia, dementia, or stroke. The result is sometimes serious limitations in social interaction. This makes it clear how much the ability to recognize and empathize with the feelings of our fellow human beings influences our daily interactions with one another.

First published on July 20, 2011

Last updated on December 18, 2025