Cells: Specialized Workers of the Brain

They are tiny and yet they do a lot of work – without them nothing in the brain would work: the cells. Thanks to their specialized properties and clever communication with each other, they determine how the brain ticks.

Wissenschaftliche Betreuung: Prof. Dr. Oliver von Bohlen und Halbach

Veröffentlicht: 01.07.2025

Niveau: mittel

- Im Gehirn gibt es zwei wichtige Zellpopulationen: Neurone und Gliazellen.

- Aktuellen Schätzungen zufolge gibt es im Gehirn etwa 86 Milliarden Neurone und ebenso viele Gliazellen.

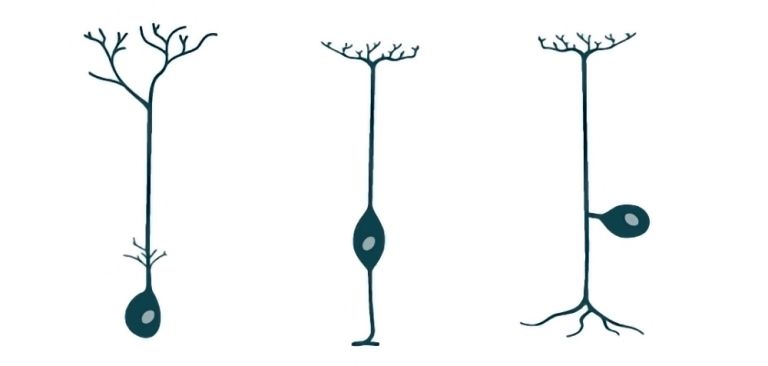

- Neurone bestehen aus einem Zellkörper und mehreren Fortsätzen: einem Axon, das Reize weiterleitet, und meist mehreren Dendriten, die Reize empfangen.

- Neurone werden in unterschiedliche Klassen aufgeteilt, je nach Anzahl der Fortsätze, dem Sitz im Körper oder der Funktion der Zelle.

- Auch Gliazellen werden in verschiedenen Typen klassifiziert. Eine wichtige Funktion erfüllen die Oligodendroglia: Sie ummanteln die Axone von Neuronen und beschleunigen dadurch die Reizweiterleitung.

Der Zellkörper oder Perikaryon ist das Stoffwechselzentrum von Neuronen. Er ist üblicherweise etwa 20 Mikrometer groß. Hier werden fast alle Stoffe synthetisiert, welche die Zelle braucht, und von dort in Axone und Dendriten transportiert. Der Zellkörper, der auch Soma genannt wird, ist gefüllt mit Cytosol.

Als Cytosol werden die flüssigen Bestandteile des Zytoplasmas der Zellen bezeichnet. Es besteht aus Wasser, darin gelösten Ionen, sowie kleinen und größeren wasserlöslichen Molekülen, wie etwa Proteinen. Das Cytosol wird von einem Netzwerk von fadenförmigen Proteinsträngen in unterschiedlicher Anordnung und Dicke durchzogen, darunter Mikrotubuli, Aktinfilamente und Intermediärfilamente, die zusammen das Cytoskelett bilden. Darin eingelagert finden sich die gleichen Strukturen wie in allen tierischen Zellen: die Organellen. Dazu zählt der Zellkern, der das genetische Material enthält, die DNA. Auch Mitochondrien, Ribosomen und der Golgiapparat gehören zu den Organellen. Eine Besonderheit der Nervenzelle ist die hohe Anzahl des rauen endoplasmatischen Reticulums, welches man einfärben und als so genannte Nisslscholle darstellen kann. ▸ Methoden: Histologie

Die Blut-Hirn-Schranke (BHS) ist eine physiologische Barriere zwischen dem Blutkreislauf und dem Zentralnervensystem. Aufgrund ihrer sehr selektiven Filterfunktion schützt die BHS das Gehirn einerseits vor Krankheitserregern und Giftstoffen. Andererseits erschwert diese Schutzfunktion zuweilen auch den Transfer von Neurotransmittern und Wirkstoffen, mit denen Ärzte eine neurobiologische Erkrankung behandeln wollen.

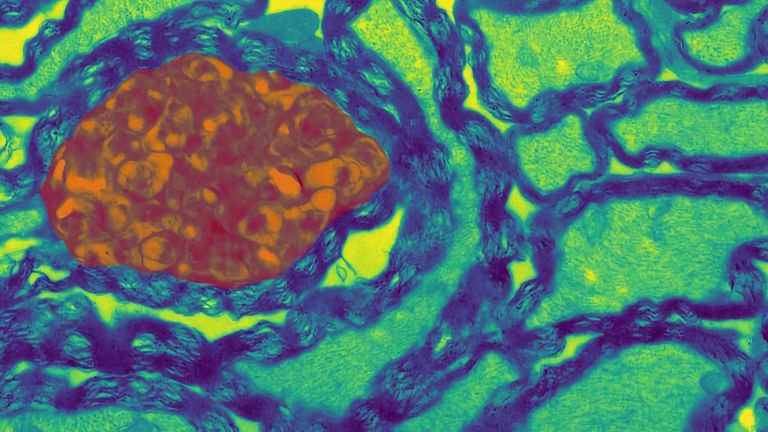

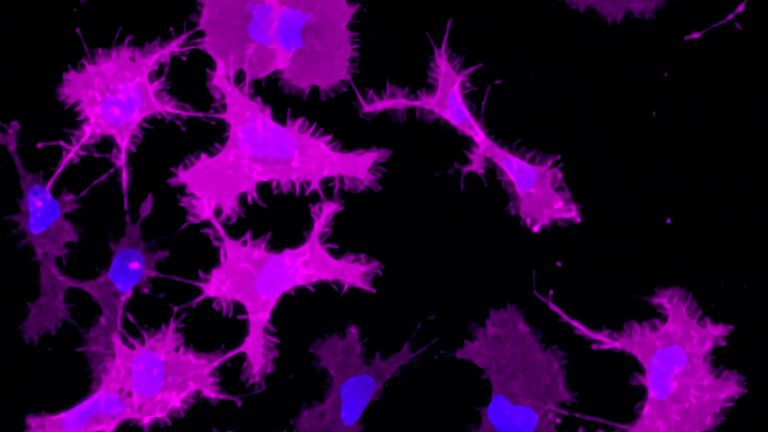

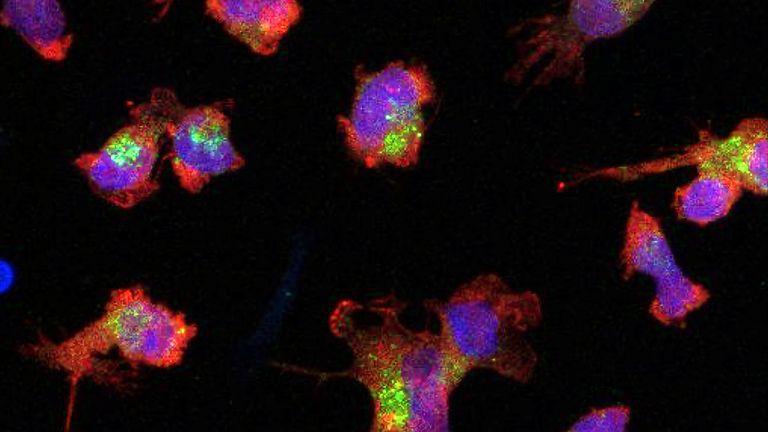

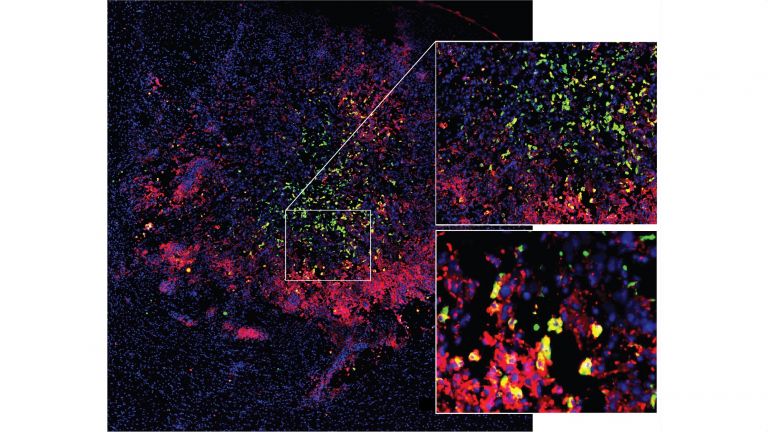

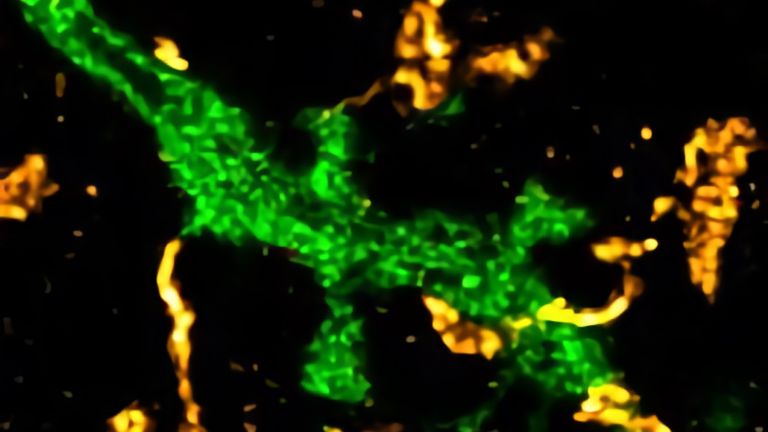

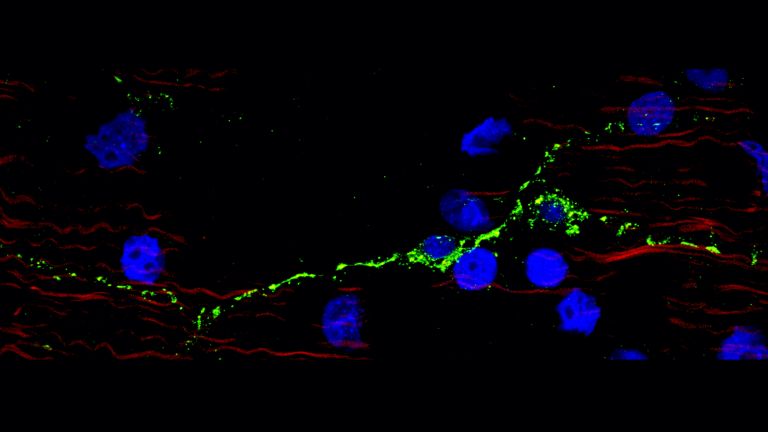

Für die BHS sind vor allem zwei Zelltypen wichtig. Zum einen die Endothelzellen der Kapillaren: Sie kleiden die Blutgefäße zum Blut hin aus. Die Zellen sind über so genannte tight junctions eng miteinander verknüpft – das sind schmale Bänder von Membranproteinen, die sich straff um die Zellen herum winden. Diese tight junctions haben einen großen Anteil an der Schrankenfunktion der BHS. Zum anderen prägen Astrozyten die BHS: Sie bedecken mit ihren Fortsätzen („Füßchen“) die Kapillargefäße. Die Astrocyten haben zwar keine direkte Schrankenfunktion, aber sie haben direkten Einfluss auf die Endothelzellen und induzieren in diesen die Funktion und Dichtigkeit der BHS, indem sie etwa die Bildung von tight junctions anregen.

Die Zahl der Zellen im Gehirn ist schwierig zu bestimmen, schließlich kann man sie nicht alle einzeln zählen. Zudem ist nicht jedes Gehirn gleich, sodass sich zwangsläufig immer Abweichungen finden. Lange arbeitete man darum mit Schätzungen, denen zufolge es im Gehirn etwa 100 Milliarden Neurone und etwa zehnmal so viele Gliazellen geben soll. Diese Zahlen finden sich in vielen Publikationen und früher auch in Lehrbüchern. Eine viel beachtete Studie, die Wissenschaftler der Universität von Rio de Janeiro im Jahr 2009 veröffentlichten, ergibt jedoch ein anderes Bild. Die Forscher lösten vier Gehirne verstorbener Männer auf, nahmen jeweils Proben von den Flüssigkeiten und zählten nach. Das Ergebnis war überraschend: Demnach beherbergt ein männliches Gehirn mit einem Gewicht von etwa 1,4 Kilogramm etwa 86 Milliarden Neurone – und etwa ebenso viele Gliazellen.

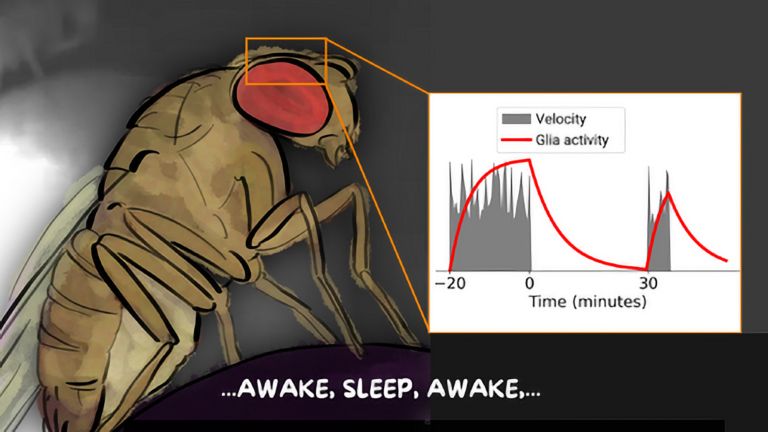

Das glymphatische Gewebe hilft dabei, Abfallstoffe und schädliche Substanzen während des Schlafs auszuscheiden. Stellen Sie es sich als nächtliches Wartungsteam des Gehirns vor, ausgestattet mit einer speziellen Flüssigkeit, um Giftstoffe auszuspülen und das Gehirn in einem guten Zustand zu halten.

Im Detail besteht das glymphatische System aus mehreren Schlüsselelementen, darunter

- die cerebrospinale Flüssigkeit (CSF). Diese Flüssigkeit fließt durch das Gehirn und transportiert Abfallprodukte ab

- Die perivaskulären Räume – Kanäle um die Blutgefäße, in denen die CSF fließt, um mit dem Gehirngewebe zu interagieren)

- Die Astrozyten und nicht zuletzt

- die interstitielle Flüssigkeit (ISF). Diese Flüssigkeit im Gehirngewebe vermischt sich mit der CSF, um Abfallstoffe aus dem Gehirn zu transportieren).

- Weitere Informationen zum glymphatischen System finden Sie bei unserem Thema ▸ Das glymphatische System

Just as no house can exist without walls and a roof, no organ can function without cells. These cells are microscopic, making them nearly invisible to the naked eye. Roughly speaking, two types of cells exist in the brain: glial cells and nerve cells, also known as neurons.

The latter, the neurons, perform the brain’s essential work. As you read this sentence, there are countless neurons – enabled by their specific structure and their sophisticated communication through synapses – that allow you to comprehend these sentences.

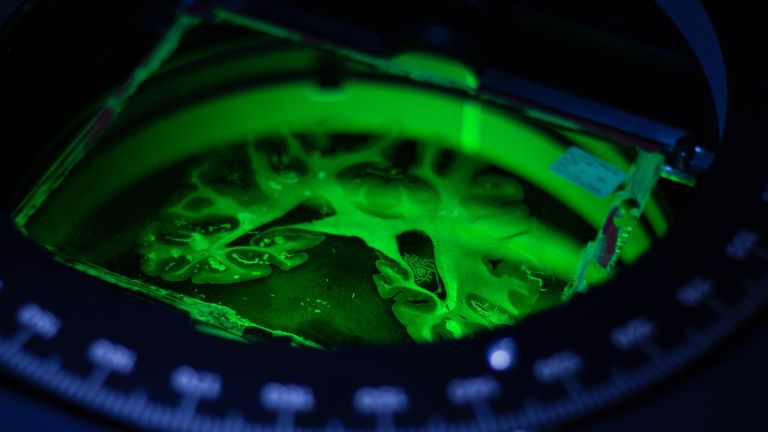

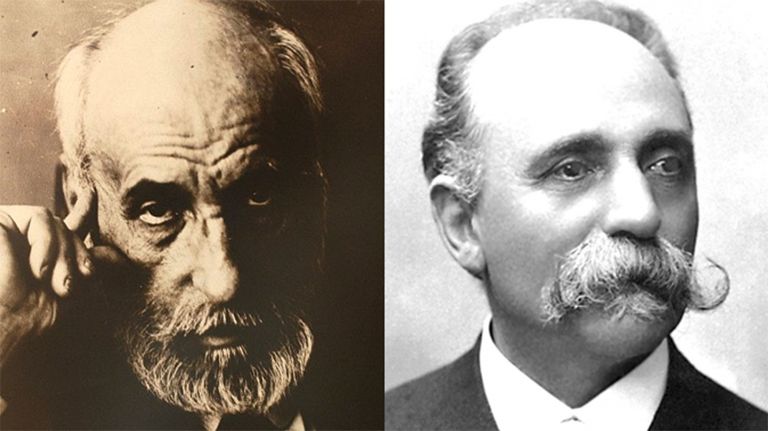

Taking a closer look at the architecture of the brain is definitely worth it – but how? Most brain cells are just 10 to 50 micrometers in size, which makes them 100 to 20 times smaller than the thickness of your pinky nail. This tiny size kept scientists puzzled for decades. Even after the invention of the microscope in the 17th century – a major step toward histology, the scientific study of biological tissue - there were still significant challenges to overcome. It wasn’t until the 19th century that scientists thought to preserve brain tissue in formaldehyde. This process allowed the otherwise jelly-like organ to be sliced into very thin sections and examined under the microscope.

At first, all that could be seen was a uniform, creamy mass – until specialized staining techniques were developed years later to make the cells visible. This breakthrough was so significant that in 1906, Camillo Golgi and Santiago Ramón y Cajal were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their contributions. ▸ The Battle over the Neuron Doctrine Even today, researchers use their methods to study brain tissue and distinguish between the two main cell types: neurons and glial cells.

Neurons – the communicators

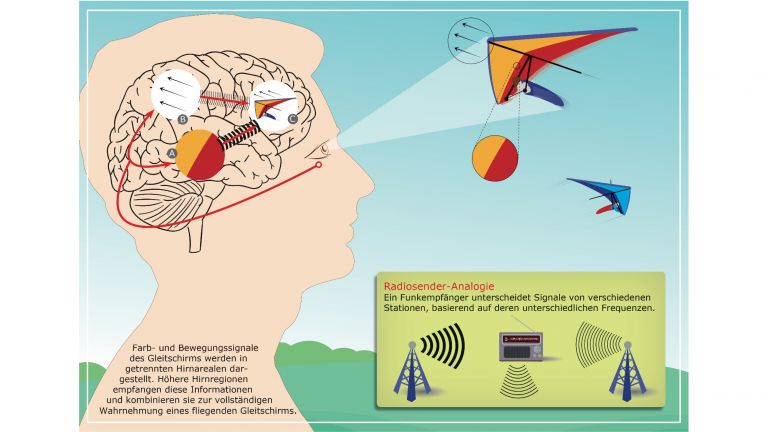

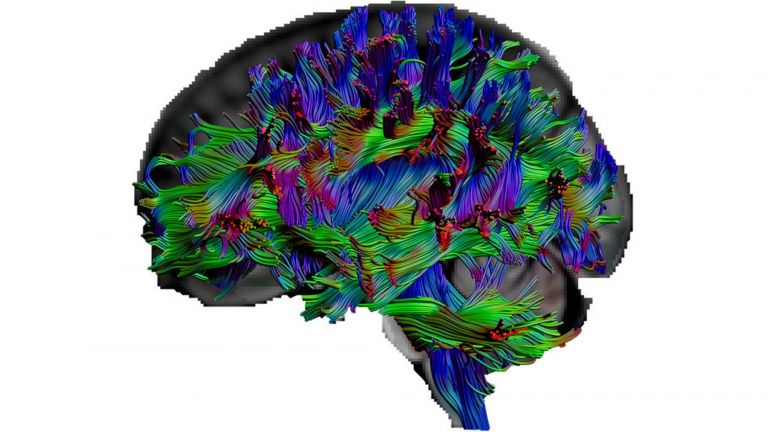

The most well-known and most essential cells are the neurons, or nerve cells. According to estimates by a research group in Rio de Janeiro, there are approximately 86 billion neurons in the human brain – almost as many as the stars in the Milky Way. Neurons regulate all your behavior, sensations, dreams, emotions, and personality by transmitting sensory impressions. While reading this article, your neurons are relaying visual information from your eyes to your brain via electrical impulses and distributing that information across different brain regions.

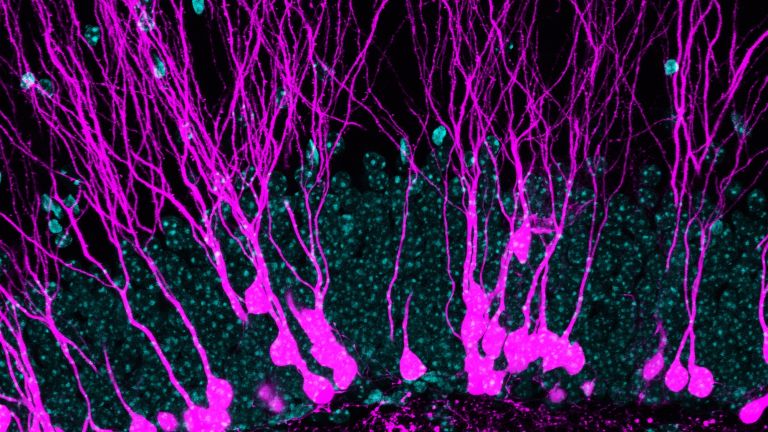

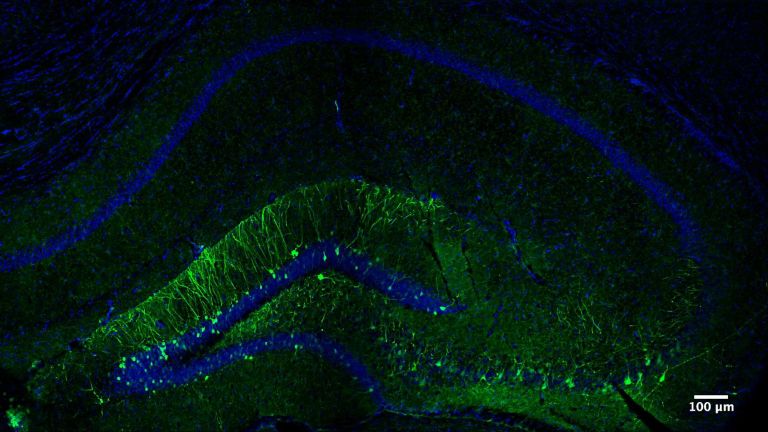

Interestingly, most of these communicative cells are not located in the largest part of the brain, the cerebrum or cerebral cortex, as one might assume. Calculations indicate that only about 19% of the neurons are found in the cerebral cortex. In contrast, approximately four-fifths of all neurons are located in the cerebellum. These neurons are vital for coordination, fine-tuning, unconscious planning, and learning motor sequences - thanks to their unique cellular structure.

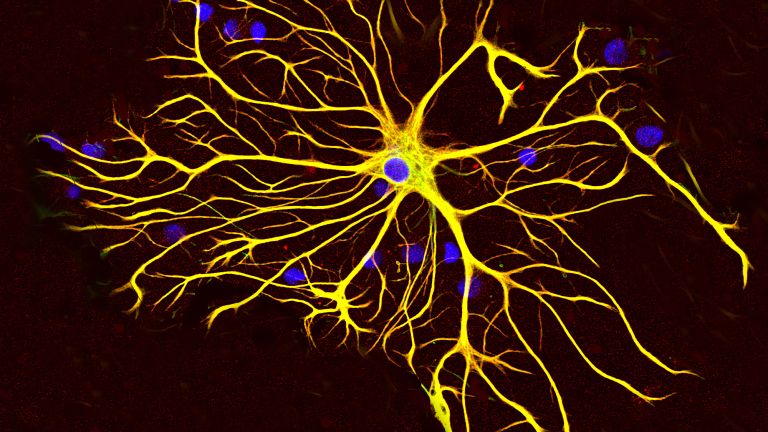

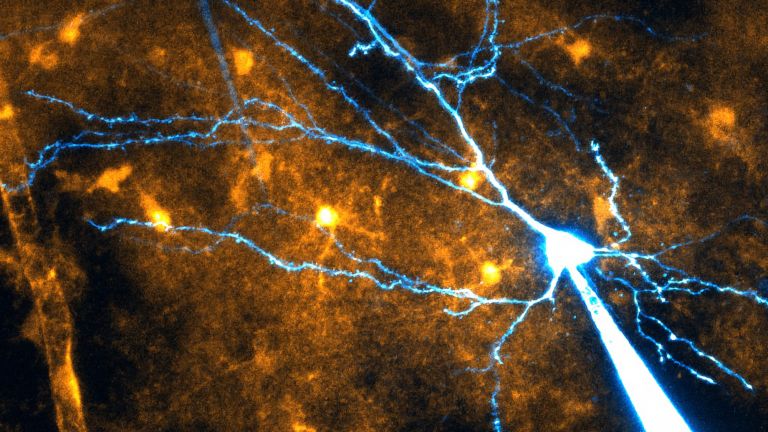

Structure of neurons

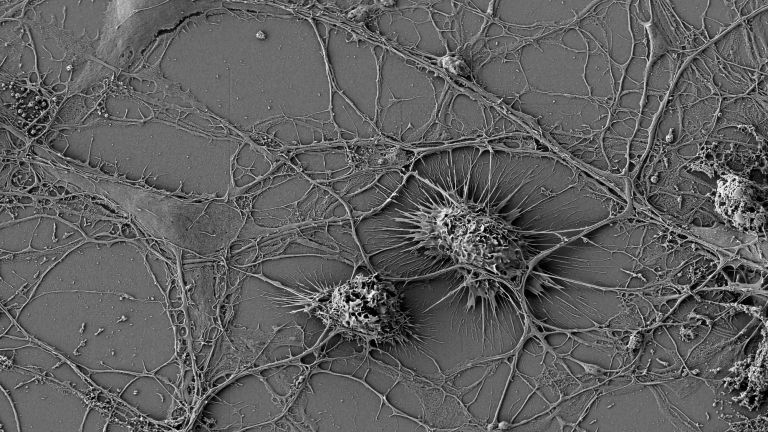

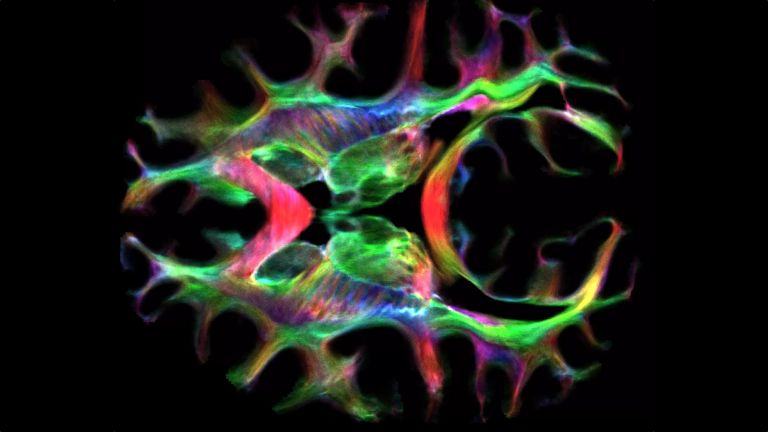

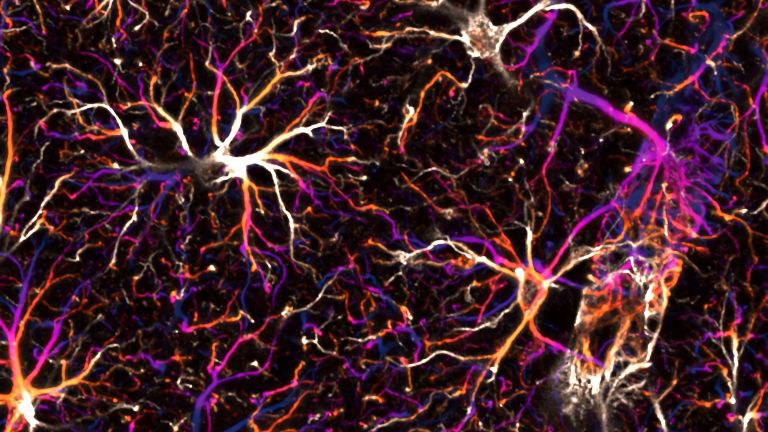

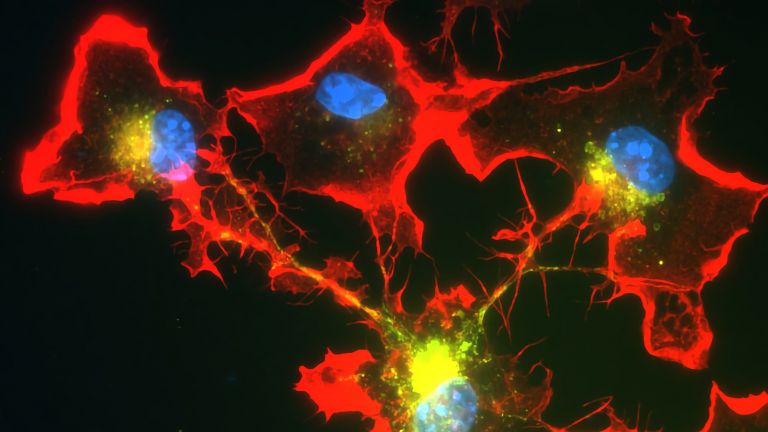

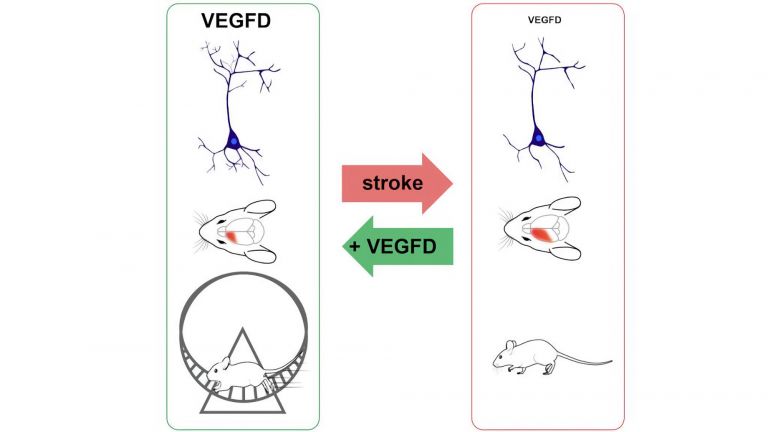

Like all cells, neurons have a cell body, which is responsible for metabolism (see information box). This cell body, also known as the soma or cytosoma, gives rise to neurites: usually one axon and one or more dendrites. Through these dendrites and axons, a cell can receive and transmit information. The axon functions like a cable, transmitting the neuron’s signals. It can extend over distances of up to a meter or more (e.g. the axon of a motor neuron of the sciatic nerve). When axons carry signals to the brain, they are referred to as afferent nerve fibers. Commands from the brain to the periphery, such as to muscles, are known as efferent nerve fibers.

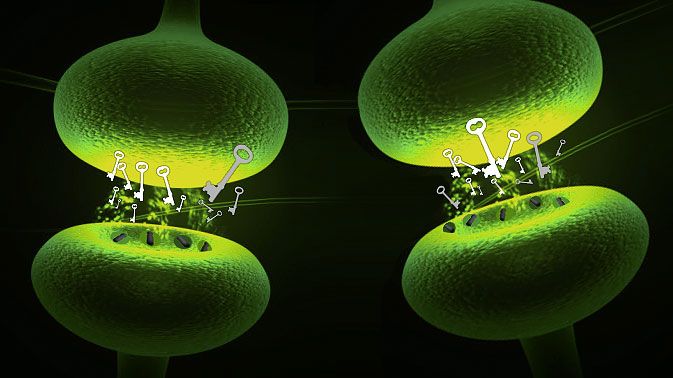

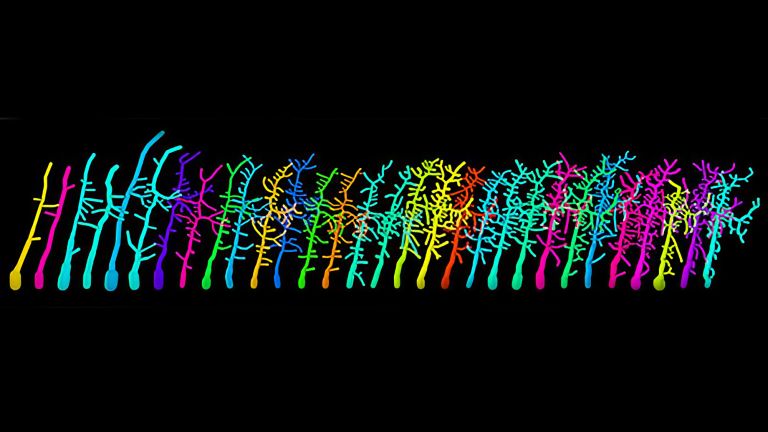

The dendrites, which are often highly branched, have small extensions called dendritic spines. These spines function like the antennas of a neuron: they connect to axons or neuronal cell bodies via synapses to receive incoming signals. A single cell body can have up to 10,000 dendritic spines. Because dendrites often extend into their surroundings like the roots of a plant, researchers also refer to them as "dendritic trees."

Different types of neurons

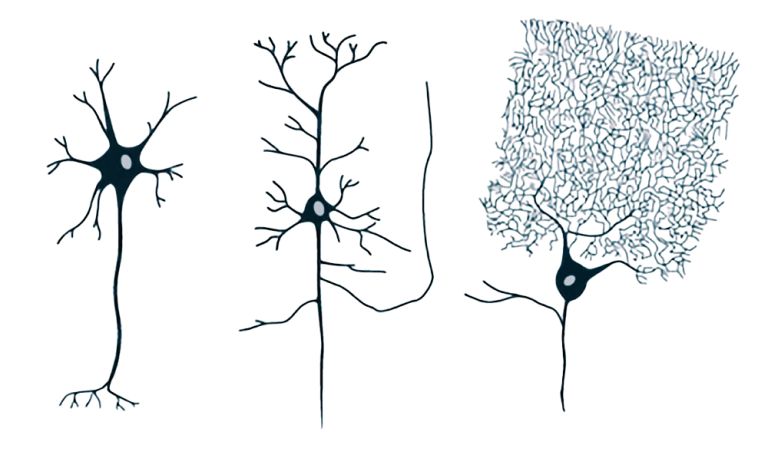

In neuroscience, various types of neurons are distinguished. These designations sometimes refer to the appearance, sometimes to the function, or the properties of the cell. As a result, a single neuron may fall into different categories, which, sometimes, can be quite confusing.

Here is an attempt to provide an overview:

One method of classification is based on the number of neurites of a neuron. Most neurons have many dendrites in addition to an axon. Therefore, they are referred to as multipolar. A bipolar neuron has one axon and one dendrite, whereas a unipolar neuron has only an axon but no dendrites. Another classification distinguishes between "spiny" or "non-spiny" neurons, depending on whether the dendrites exhibit small spines like a rose or not. These spines mostly form excitatory synapses.

The location within the body or the specific function of a cell can also be crucial for its designation. Neurons whose neurites are located on the sensory surfaces of the body, for example in the inner ear or the retina of the eye, are referred to as sensory neurons. They relay information to the nervous system. Motor neurons (or motoneurons) have axons that form synapses with muscles and trigger movements. Most neurons in the nervous system, however, are connected with other neurons. These are referred to as interneurons. These interneurons have only short axons and contact nerve cells in the immediate vicinity. Neurons that are in contact with other nerve cells but whose axons extend to distant brain regions are called projection neurons.

Another classification is based on the chemical properties of neurons. Cells that release the neurotransmitter acetylcholine at their synapses are referred to as cholinergic. Such cholinergic cells, for example, are involved in the control of voluntary movements.

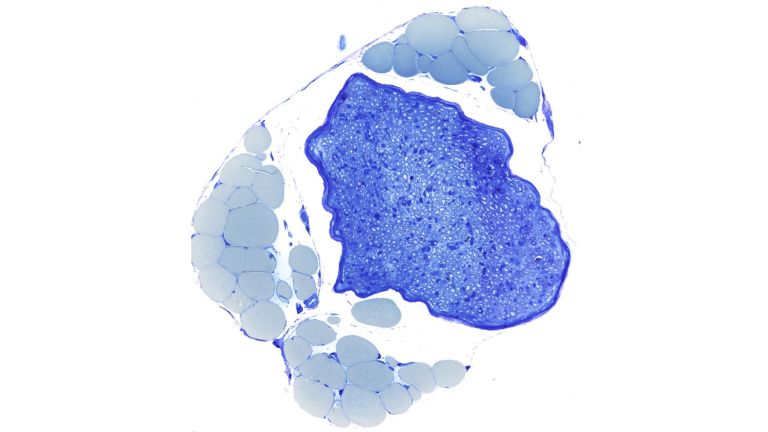

To add to the confusion, some neurons are also classified based on their appearance and the structure of their dendritic trees. For example, the cell body of pyramidal cells, which are relatively large with a diameter of up to 100 micrometers, resembles a triangle. Stellate cells, on the other hand, live up to their name. Granule cells have been named because they appear grainy in cross-sections of brain tissue. In contrast, Purkinje cells that can be found in the cerebellum are simply named after their discoverer.

Empfohlene Artikel

Glial Cells – more than “supporting glue”

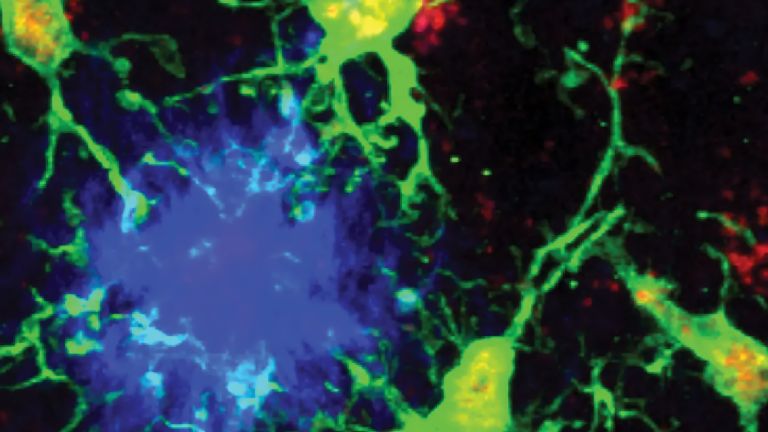

Despite contrary evidence, two persistent rumors exist about the second important cell population in the brain, glial cells. The first concerns their number: there are supposedly ten times as many glial cells as neurons. However, a study from 2009 suggests that there are probably as many glial cells as neurons. The second rumor relates to the origin of the cells' name: the Greek word "glia" means glue. For a long time, it was believed that the exclusive function of glial cells was to isolate, support, and nourish neighboring cells. Mark F. Bear illustrates this role in the book "Neuroscience" by stating: "If the brain were a chocolate-chip cookie and the neurons were chocolate chips, the glia would be the cookie dough that fills all the other space and ensures that the chips are suspended in their appropriate locations."

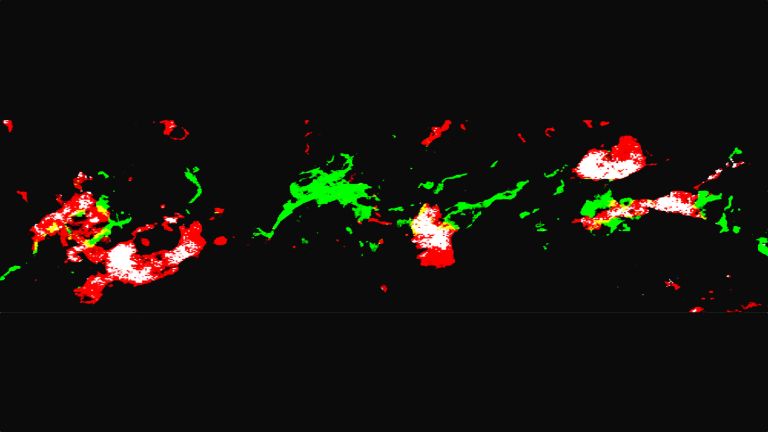

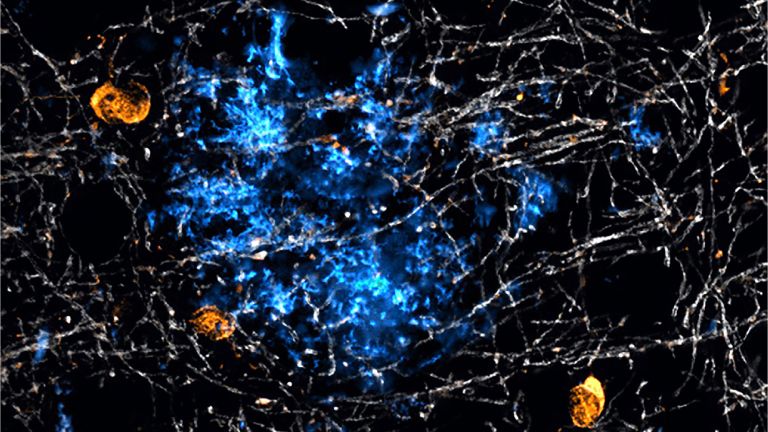

In the early 1980s, a German and an American neuroscientist independently discovered that the membranes of astrocytes, the most common type of glial cell in the brain, also possess receptors for neurotransmitters, allowing them to interact with other cells. In addition, astroglia, astrocytes, or spider cells in the central nervous system have the task of acting as traffic controllers and gatekeepers: they regulate the chemical environment in the extracellular space by absorbing potassium ions or even the neurotransmitter glutamate. This allows them to influence the functions of neighboring cells. They are also involved in the blood-brain barrier, which ensures that only certain substances can enter the brain (see info box) and in the glymphatic system.

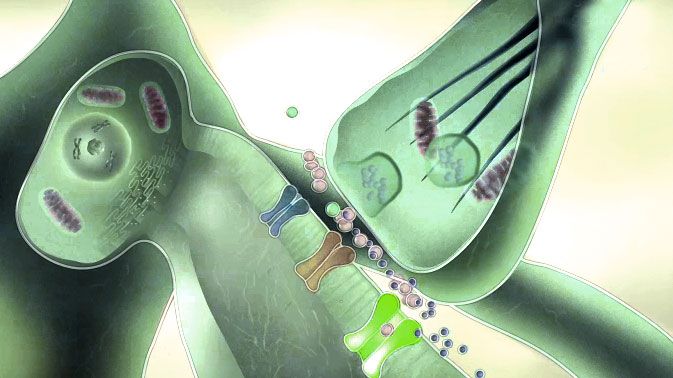

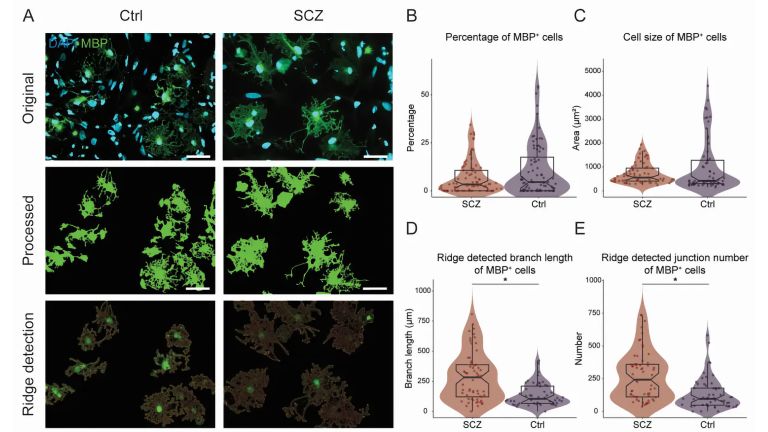

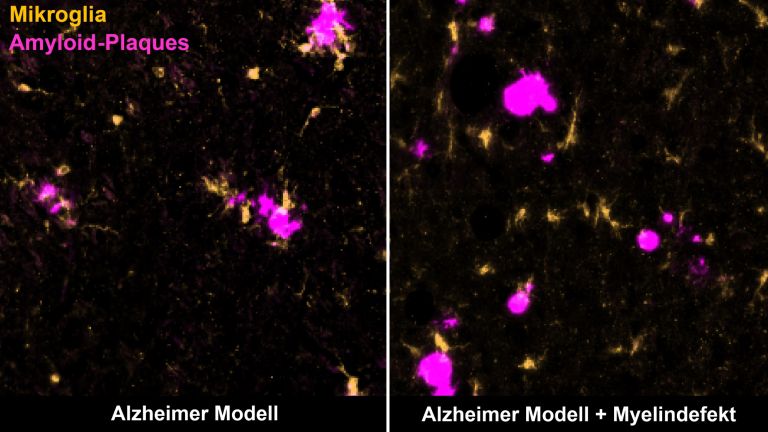

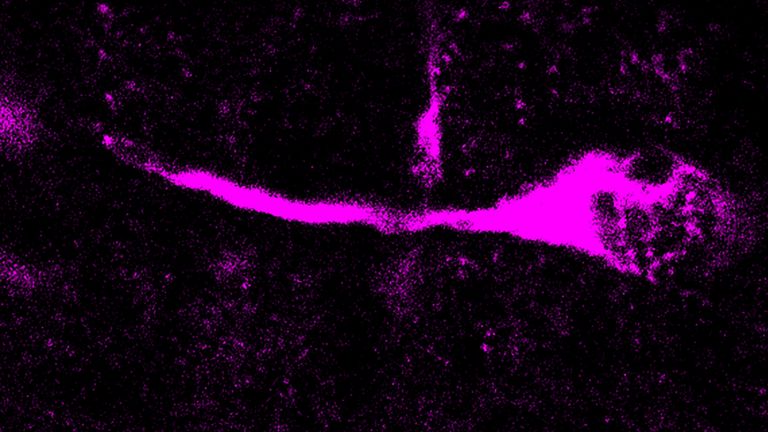

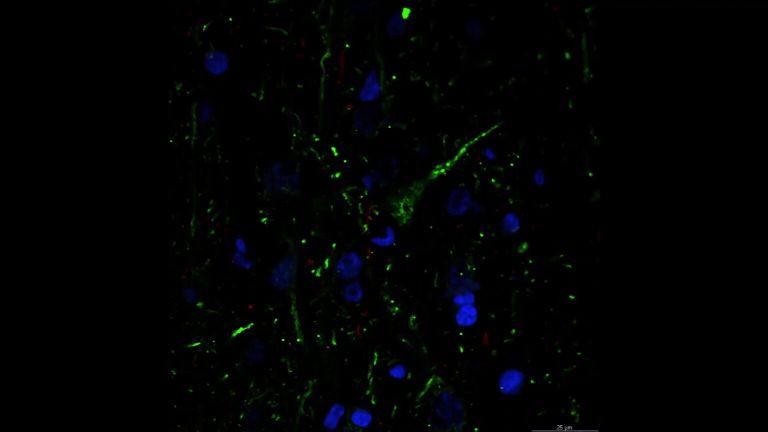

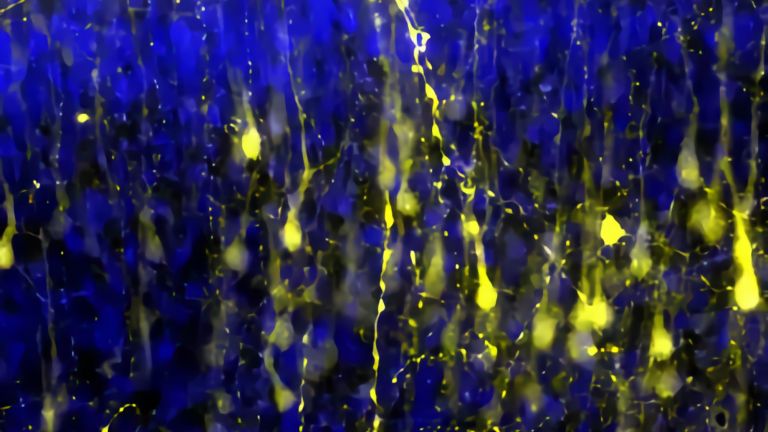

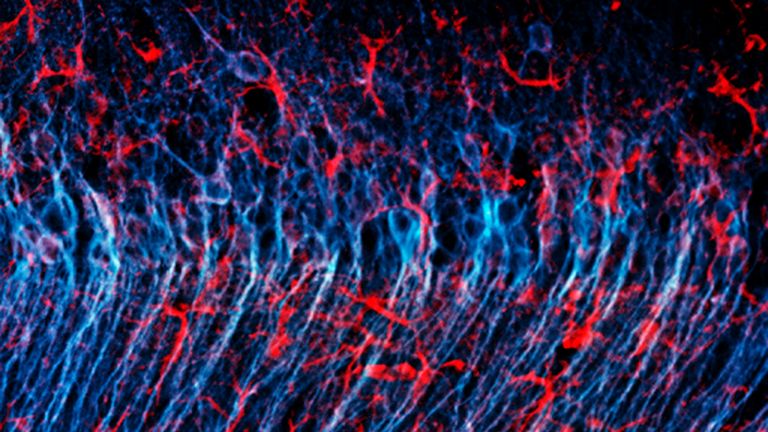

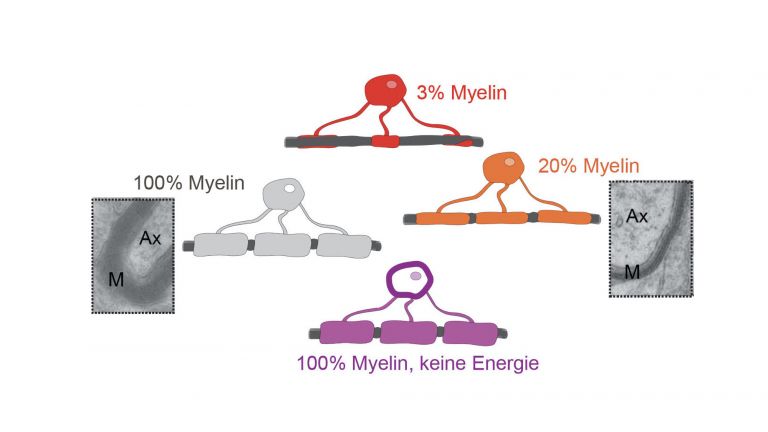

Rapid transmission thanks to myelin sheath

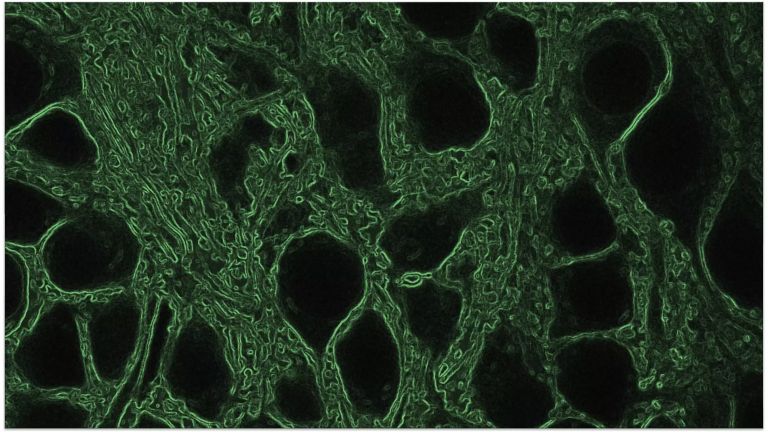

Oligodendroglias (also known as oligodendrocytes) in the central nervous system, as well as Schwann cells in the peripheral nervous system, perform a very special function. They form lipid-rich membranes, which they wrap around an axon in several layers to insulate it. This creates what is called a myelin sheath (myelin: Greek for ‘marrow’) around the axons. Since an axon encased in such a sheath resembles a sword in a sheath, scientists also refer to these sheaths as myelin sheaths.

The myelin sheaths accelerate the transmission of nerve impulses along the axons – thanks to the myelin sheath, they become true data highways. The trick is that the myelin sheath is repeatedly interrupted by small gaps called “nodes of Ranvier”. The transmission of impulses in the axon occurs via electrical impulses. However, since excitation cannot occur in the areas covered by the myelin sheath, the electrical impulse essentially jumps from one node of Ranvier to the next node of Ranvier. Researchers call this saltatory conduction. It makes the information transmission in our brain so rapid – and demonstrates how closely glial cells and neurons in the brain work together to enable us to do what we do every day.

First published on April 10, 2012

Last updated on July 7, 2025