Learning on a Pinhead

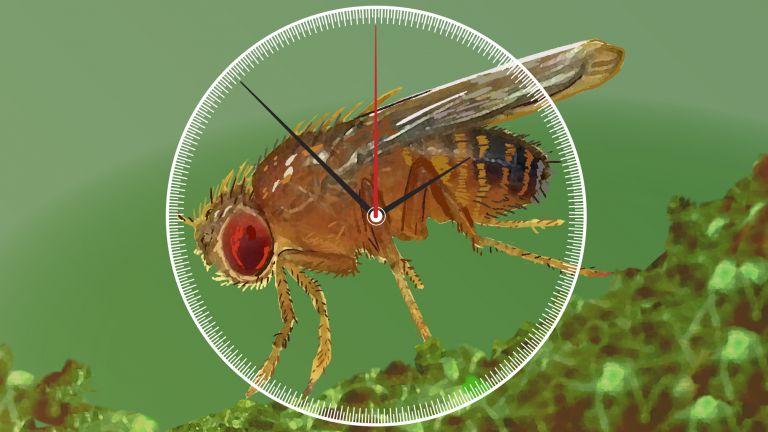

Their lives are short and their brains are tiny, but fruit flies still have enough brains to learn. And like humans, their ability also declines with age.

Scientific support: Prof. Dr. Björn Brembs

Published: 19.01.2026

Difficulty: easy

- Despite all their differences, humans and flies face similar challenges when it comes to foraging, reproduction, and danger.

- The olfactory system of Drosophila is similar in its general anatomical organization to that of vertebrates, but has significantly fewer cells.

- Fruit flies learn to associate odors with negative or positive stimuli via neurons in the mushroom body.

- There is also second-order conditioning, where already conditioned odors are linked to another odor.

- Fruit flies can also develop relief memory, for example, if a scent only appears when pain subsides.

- In old age, their brain apparently also attempts to compensate for declining memory.

The everyday lives of humans and the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster are fundamentally different. We go to work, meet friends in our free time, play sports, go on trips, and much more. The life of a fruit fly is more straightforward. They prefer to make themselves comfortable in overripe fruit, using it as a source of food or for laying eggs. Nevertheless, humans and flies face similar challenges: foraging, reproduction, and responding to danger require appropriate behaviors and quick decisions. This requires a complex nervous system, whose building blocks and basic processes are surprisingly similar in flies and mammals.

For the fruit fly, it can be vital to distinguish between scents that promise food or danger. The olfactory system of Drosophila is similar in its general anatomical organization to that of vertebrates, but has significantly fewer cells. This makes it an ideal model system for studying odor processing in the brain.

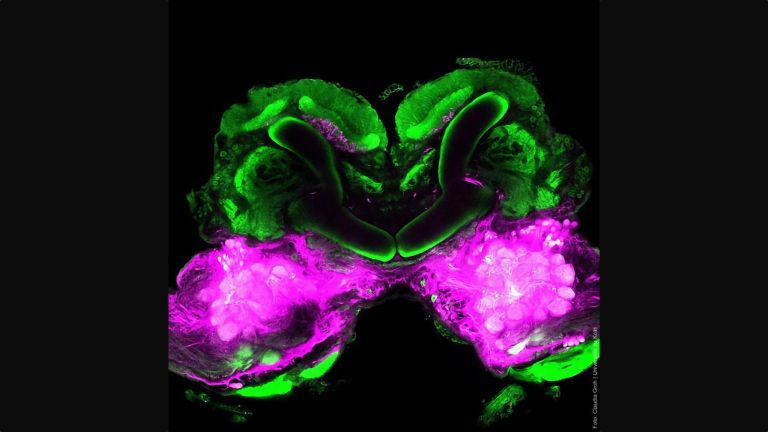

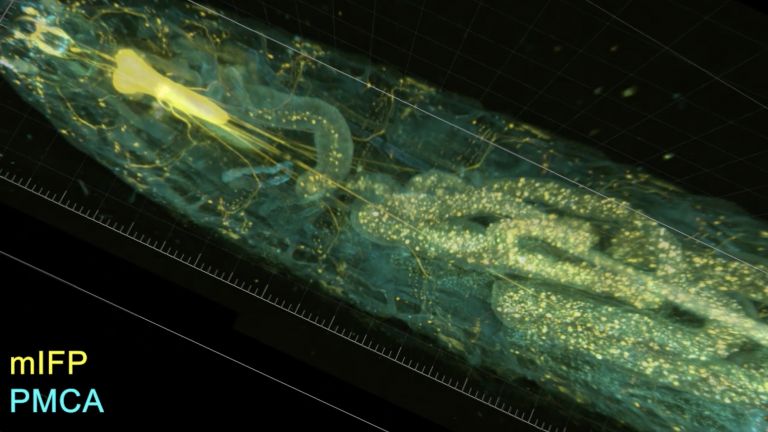

"When something is learned, the effectiveness with which synapses transmit signals changes," says neurobiologist and geneticist André Fiala from the University of Göttingen. "It becomes stronger or weaker." When a stimulus is processed, the synapses of entire networks of neurons change. For researchers like André Fiala, it is a challenge to examine a large number of synapses at the same time. In larger animals, millions of nerve cells are involved in processing a smell. Observing them all at the same time is almost impossible. "That's why we study fruit flies, which have comparatively few neurons," says Fiala.

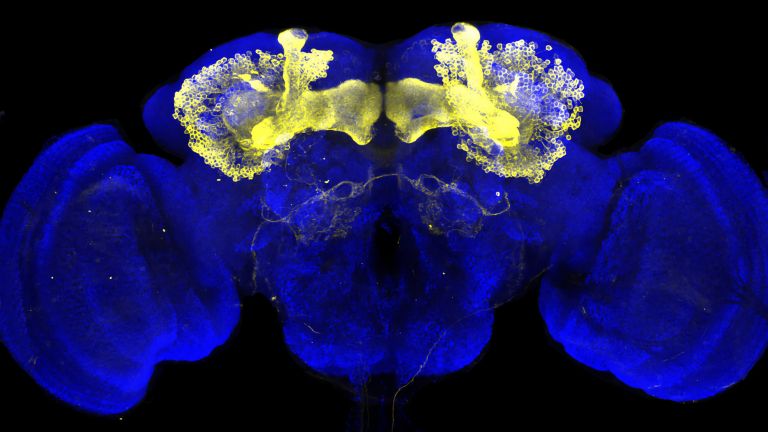

Fiala and his colleagues are interested in the phenomenon of conditioning – when the fruit fly learns to associate a smell with something positive or negative. Odor conditioning takes place in the fly's brain in what is known as the mushroom body. Its structure and connections are similar to higher brain centers in mammals. Odors are reflected in the activity patterns of Kenyon cells in the mushroom body. Just as in the mammalian brain, positive or negative stimuli activate neurons that release the neurotransmitter dopamine, thereby signaling reward or punishment. The combination of scent stimulus patterns and the release of dopamine causes the synapses of the Kenyon cells to change.

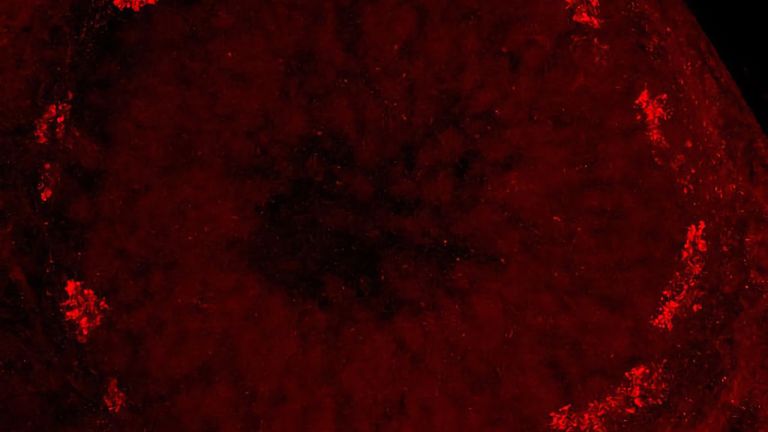

Sugar or electric shock

The researchers give the animals sugar as a positive stimulus – a reward. Small but unpleasant electric shocks serve as a negative stimulus – punishment. Fiala himself has discovered that during certain learning processes, coordinated patterns of synaptic activity diverge; in a sense, they no longer oscillate in unison. A downstream neuron that reads the activity of these synapses thus receives a weaker input. "When a scent is associated with a negative stimulus, the synapses that control a particular neuron become weaker," explains Fiala. Normally, this is a neuron that triggers an attraction to the scent. Since this neuron is now weaker, the animals are less attracted to the "negative" scent. Conversely, in reward learning, synapses connecting to neurons that trigger avoidance behavior are weakened. In this case, the animals are more attracted to the scent.

Once the flies have learned to associate a certain scent with an electric shock or sugar water, they can also link this conditioned scent with a second scent. "These second-order conditionings activate complex feedback loops in the fly's brain," says Fiala. "When the new scent is encountered, it is associated not only with the old scent, but also with reward or punishment."

Pain, pain, go away!

There's no question about it: punishment in the form of pain from an electric shock is an unpleasant experience at first. "But it can be nice when the pain subsides," says Bertram Gerber from the Leibniz Institute for Neurobiology. The reverse is also true: "It's nice to receive a reward, but it can be very frustrating when it ends." What exactly a fly learns in response to rewards and punishments is a question of timing. Let's put ourselves in the fly's shoes. "A stimulus such as a scent can only be considered the cause of punishment if it occurs before the punishment," says Gerber. "For example, if you present a scent to the animals and they then experience an electric shock, the animals interpret the smell negatively as the cause of the pain stimulus." However, it is different if the animals first experience the pain stimulus and are only presented with the scent once the pain subsides. "Then they rule out the scent as the cause of pain and interpret it positively." In this case, we speak of relief learning: the animals associate the scent with the "relief" of diminishing pain. The researchers can tell whether the animals interpret the scent positively or negatively simply by whether the animals flee from the scent or gravitate toward it.

As mentioned above, punishments and rewards are mediated by dopamine-releasing neurons. Gerber and his colleagues have now asked themselves whether, for example, the same punishment neuron can trigger both the usual negative punishment memory and the positive relief memory. The answer: it can. "If you present a scent and then artificially activate a punishing dopamine neuron, you get a negative punishment memory." If you reverse the order and activate the neuron before presenting the scent, you get a relief memory.

Recommended articles

Learning in old age

Furthermore, timing plays another crucial role in learning. The age at which a living being learns makes a big difference. Fruit flies have a lifespan of only two weeks to two months. And as they age, they are less and less able to form memories. Their memory performance declines after just 20 to 30 days. Geneticist Stephan Sigrist from the Free University of Berlin and his colleagues are investigating how the aging process is causally linked to the mechanisms of memory formation. This is not so easy, because a lot changes in the brain as we age. "And not everything is equally responsible for declining mental performance," says Sigrist. "Some processes could rather be the brain's attempt to counteract cognitive decline."

Sigrist and his colleagues are particularly interested in the output synapses of the mushroom body. These transmit the output signals of the Kenyon cells. The output synapses are in turn linked to neurons that presumably send the mushroom body's processing power directly to the premotor centers in order to trigger behaviors such as flight or approach.

Sigrist and his colleagues were able to show that presynaptic structures, structures that send signals to downstream neurons, enlarge in the course of aging. This plasticity is found both at the output synapses of the Kenyon cells in the mushroom body and throughout large parts of the fly brain. "The remodeling of the presynapses most likely changes the communication between the nerve cells," says Sigrist. Originally, he and his colleagues thought that this remodeling was responsible for fewer memory traces being created in old age. "We now assume that, on the contrary, the remodeling supports the formation of memory traces."

Compensating for declining memory performance

The researchers base their assumption on fruit flies that have been genetically modified so that they are no longer able to activate the plasticity of the presynapse. As a result, they found it difficult to form memory traces. "However, if a specific protein called Bruchpilot, which organizes the enlargement of the presynapse, is genetically upregulated in these animals, they begin to form memories very effectively again." Sigrist's hypothesis: "This plasticity of the synapse is a tool that the aging brain uses to get the formation of new memories back on track. It serves to compensate for declining memory performance." Does something like this also exist in humans? Given the many similarities, this cannot be ruled out – and it is another exciting lead that memory researchers could follow.

Further reading

- Bilz F et al.: Visualization of a Distributed Synaptic Memory Code in the Drosophila Brain. Neuron. 2020;106(6):963-976.e4 (full text). doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2020.03.010.

- Weiglein A, Thoener J, Feldbruegge I, et al. Aversive teaching signals from individual dopamine neurons in larval Drosophila show qualitative differences in their temporal “fingerprint.” J Comp Neurol. 2021;529(7):1553-1570 (to abstract). doi:10.1002/cne.25037.