Flies? Why flies?

Flies and humans are worlds apart. However, if you look at the brain and the genome of this tiny insect, you will see that many things work in a very similar way.

Scientific support: Prof. Dr. Martin Göpfert

Published: 17.01.2026

Difficulty: easy

- The fruit fly Drosophila is the superstar among laboratory animals: small, easy to care for, and prolific. A new generation of flies grows up in just 10 days.

- Many genes known today were first discovered in fruit flies. This works in screening tests in which, genetic mutations are induced and then the insects are examined for altered characteristics, which are described. Many of the genes found in this way also occur in a similar form in humans and function in a very similar way in our bodies.

- The structure and function of nerve cells, and even the structure of neural networks, are similar in humans and flies. And since flies can learn a lot and behave in many different ways, they are also well suited for investigating neuroscientific questions.

- Fruit flies are particularly accessible for experimentation. Their genes can be specifically activated, blocked, or altered in their function in individual tissue or cell types. The activity of individual cells or molecules can also be easily manipulated and observed in living animals. Flies are therefore well suited for the study of molecular and cellular mechanisms.

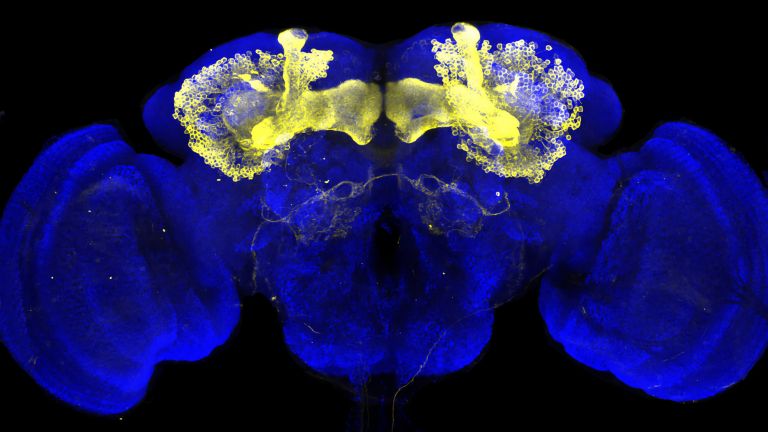

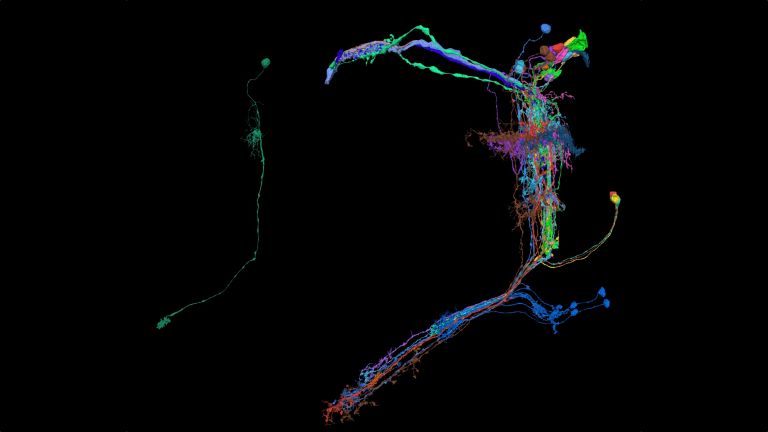

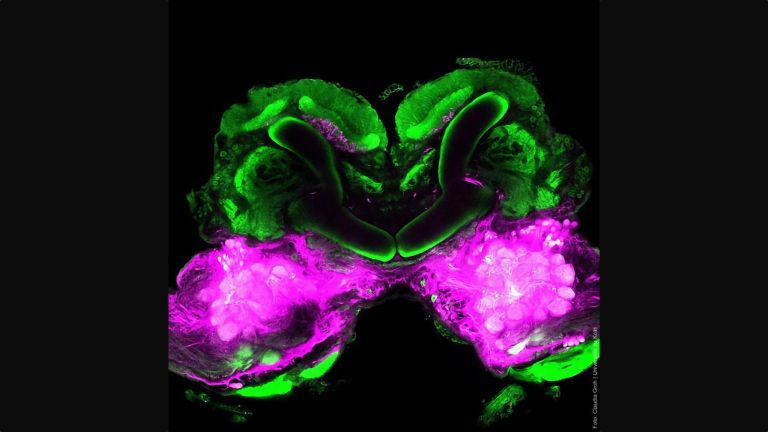

- In the fly's brain, the mushroom body combines important functions in a compact space that are distributed across different regions in the human brain: the integration of sensory impressions, the formation and storage of memories, and a decision-making center for behavioral control. The mushroom body is therefore particularly well suited for integrative studies of how molecules, nerve cells, and networks interact to produce situation- and experience-dependent behavior.

The list of experimental tricks that can be used to study Drosophila melanogaster is long and constantly growing. Here is a selection of the most popular techniques:

- Genetic screening Flies are genetically manipulated in a targeted manner and their offspring are examined for altered characteristics over several generations. Thanks to particularly stable inheritance and numerous marking options (e.g., eye color), the changes found can be assigned to specific chromosomes, chromosome regions, and very precise gene regions. This is possible because the complete genome of Drosophila melanogaster – the first animal ever – has been precisely sequenced.

- Tissue-specific gene expression With the discovery of transposons, gene segments that produce proteins with which they can cut themselves out and reinsert themselves elsewhere in the genome, it became possible to specifically modify the fly genome. In a popular variant, one group of flies receives a gene whose protein can activate the transcription of other genes, coupled with a DNA sequence that is only accessible in certain tissues. Another group of flies receives a gene whose transcription is stimulated by the activator of the first group. When the two groups are crossed, flies are produced in which the transcription of the second gene is activated only in the tissue selected in the first group. In this way, specific genes can be expressed in selected cells, such as precisely defined nerve cells.

- Targeted gene modification If you want to test whether a known gene plays a role in certain processes, you can use various methods to specifically modify its function and then examine what happens in the respective process. The modifications can be made, for example, with the “gene scissors” CRISPR/Cas9 or with RNA interference, in which the gene itself remains unchanged, but the RNA transcribed by it is deactivated.

- Optogenetics Here, a nerve cell or groups of nerve cells are equipped with a “switch” consisting of a transgene-expressed, light-sensitive protein. The result is a light-sensitive ion channel that can be quickly and temporarily activated or deactivated with a light stimulus. As a result, the switch turns the associated nerve cells on and off with light.

The techniques can be combined with each other.

The fruit fly is not the only animal that can be used to investigate exciting neuroscientific questions. The competition comes with its own strengths and weaknesses:

- The worm Caenorhabditis elegans means “elegant new rod” – a grandiose name for a threadworm that is only one millimeter in length. The worms are very easy to care for, easy to study and manipulate using molecular genetics, can be frozen, and have a precise number of cells with precisely defined fates from the outset. With a maximum of 385 neurons, the worm's nervous system is very manageable – but so is its behavioral repertoire.

- The sea slug Aplysia californica is known in English as the “California sea hare” and is about the same size as its land-dwelling namesake. Sea hares have particularly large nerve cells and a simple nervous system. Electrophysiological studies work very well, and Nobel Prize winner Eric Kandel used this to elicit the cellular and molecular basis of learning from the snails. Molecular genetic tools, on the other hand, are rather limited.

- The fish The zebrafish, Danio rerio, is the fruit fly of vertebrates. This model organism also comes with a well-stocked molecular biology toolbox, but the effort and time required per generation are much greater than with Drosophila. Zebrafish lay hundreds of transparent eggs, in which a fish larva grows within 24 hours. The entire development of the fish can be easily observed under a microscope, and Danio rerio is also well suited for more complex behavioral biology studies.

- The mouse Many molecular biology and genetic tools can also be used on mice. As mammals, they are much more similar to humans than most other model organisms and thus promise research results that are more relevant to humans, especially when it comes to complex behavior. However, their similarity to humans also complicates many studies. Development takes longer and takes place in the womb, which is difficult to access. Due to their high sensitivity, there are also higher animal welfare requirements.

In Kurt Neumann's 1958 horror film The Fly, terrible things happen to a researcher after his body is accidentally fused with that of a fly in an experiment. In contrast, real research, which has revolved around the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster in many disciplines for more than 100 years, has so far remained free of gruesome side effects. However, reality is hardly inferior to the film in terms of vision: the small insect, also known to many as the fruit fly or vinegar fly, is expected to answer big questions and has already done so: How does a complex body grow from a fertilized egg cell? How do diseases develop? How does the brain learn?

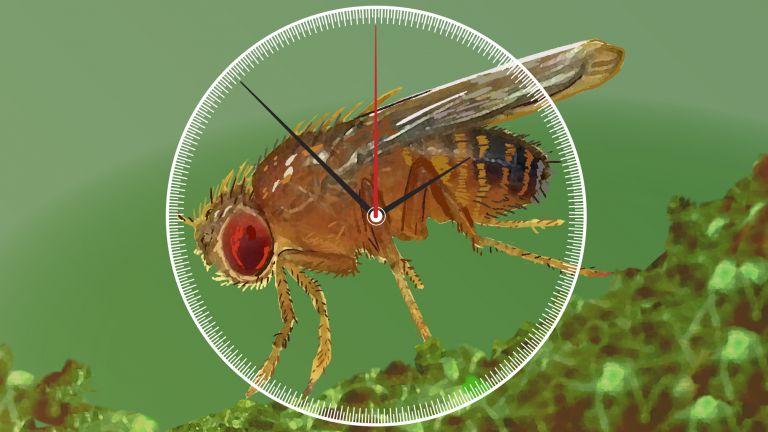

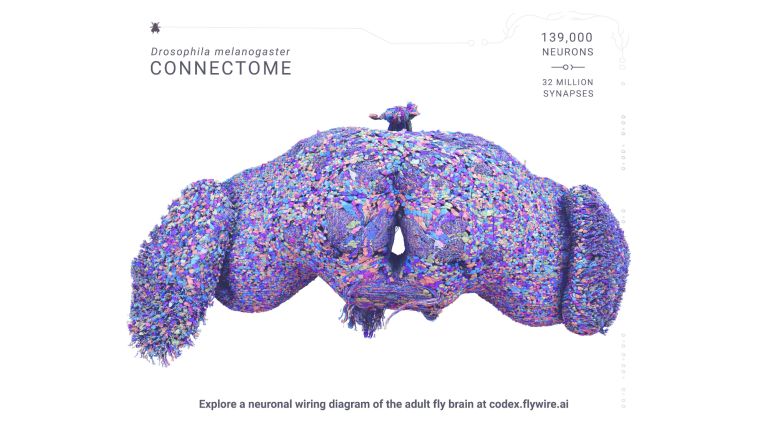

The last question in particular seems presumptuous. Only 100,000 neurons work in the Drosophila brain; in humans, 86 billion nerve cells are clustered together, almost ten thousand times as many. But what we know about the fly so far makes it clear that the modest fly brain can teach us a lot about learning. It is not without reason that Drosophila is the favorite laboratory animal in research. As early as 1910, the American zoologist and geneticist Thomas Hunt Morgan appreciated the advantages of the little fly for his pioneering work in genetics, for which he later received the Nobel Prize. Fruit flies are small, easy to care for, extremely fertile, and reproduce quickly.

A generation takes just ten days. In their “fly room,” a laboratory measuring just 35 square meters, Morgan and his team initially needed little more than ripe bananas, milk bottles, and magnifying glasses to observe how certain characteristics were passed on from generation to generation in thousands of flies.

It's all in the genes

It quickly became clear that flies were a stroke of luck for biological research in many other ways. The animals are extremely easy to study and manipulate, both genetically and in terms of cell and molecular biology (see box “The molecular genetics toolbox”). Morgan and many others who soon followed in his footsteps initially unlocked the secrets of Drosophila by exposing the animals to mutating X-rays or chemicals. They then studied the effects of these mutations in painstaking detail using so-called screens and assigned them to specific positions on the chromosomes.

Christiane Nüsslein-Volhard and Eric Wieschaus used this method in 1980 to characterize 600 mutations in 120 genes that alter the segment pattern of fly larvae – work for which they later also received the Nobel Prize. In doing so, they deciphered crucial mechanisms of embryonic development. And, as it later turned out, these genes also orchestrate development in many other animals, including humans, and are involved in disease processes – including in the nervous system.

The surprising similarity between fruit flies and other organisms that are only very distantly related to them has since been confirmed time and again. In 2000, the fly's genome was completely decoded; and a few months later, in 2001, the first, not yet complete sequencing of the human genome was published. Since then, it has become clear that many human genes have corresponding counterparts with similar structures and/or functions in the fly. This applies, for example, to 77 percent of the disease-relevant human genes known in 2001. The list is constantly updated in an online database called “Flybase.”

Highly capable of learning

The fly's brain is also more similar to the human brain than one might initially assume. Although it is only the size of a poppy seed, it accomplishes a great deal in this small space. For example, flies have a very good sense of smell and sight and constantly compare this and other sensory information with further details in order to make decisions, navigate through three-dimensional space, find food, avoid dangers, and charm or fight other flies. ▸ Smart flies

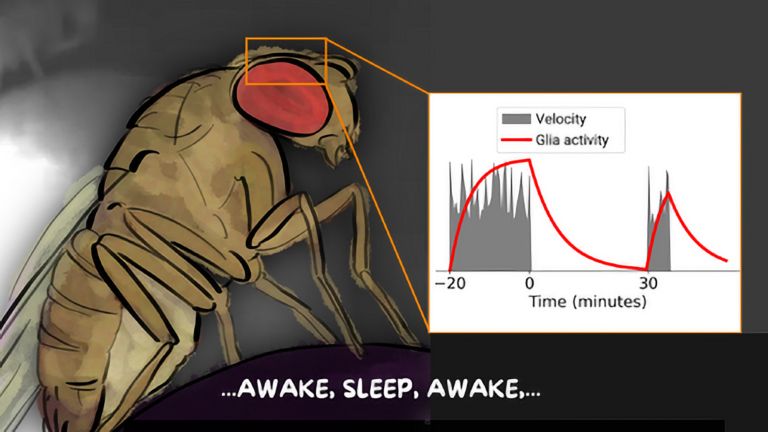

Only those who are capable of learning can develop such a complex behavioral repertoire. Flies learn, draw on memories, and forget some things, just like humans. Even though the everyday lives of Drosophila melanogaster and Homo sapiens are worlds apart, the basic challenges of survival are so similar at their core that proven learning mechanisms have been preserved throughout evolution ▸ Learning on a pinhead – just like the genes involved. As early as the 1960s and 1970s, US researcher Seymour Benzer discovered genes that affect the learning ability of flies. Genes with the evocative names dunce and rutabaga, for example, encode the blueprint for enzymes that play an important role in intracellular signaling cascades, which are essential for learning processes. Since then, researchers have identified human counterparts for these and many other neurobiologically relevant fly genes.

There are therefore fundamental similarities between Drosophila melanogaster and Homo sapiens. This makes it possible to use studies on flies to discover details relevant to humans about how experiences and learning processes, but also diseases, change the neural circuits that control behavior.

Fly research at the forefront

The fruit fly makes it easy for researchers to examine it experimentally and pursue questions that are difficult or impossible to investigate in humans or other laboratory animals. Experimental techniques for specifically manipulating the fly's genome have been around since the 1980s and are constantly being refined. Specific genes or gene segments can be selectively activated, blocked, or altered in their function in individual tissue or cell types, including through the addition of transgenes, i.e., gene segments from other species. Such changes can be permanent or designed to be switched on and off by specific signals.

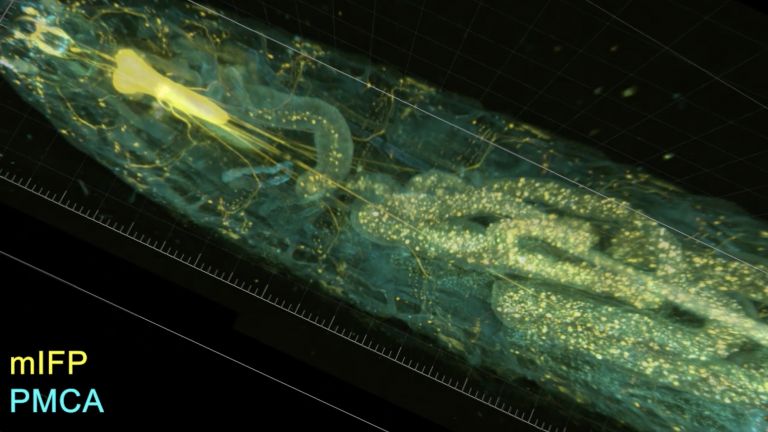

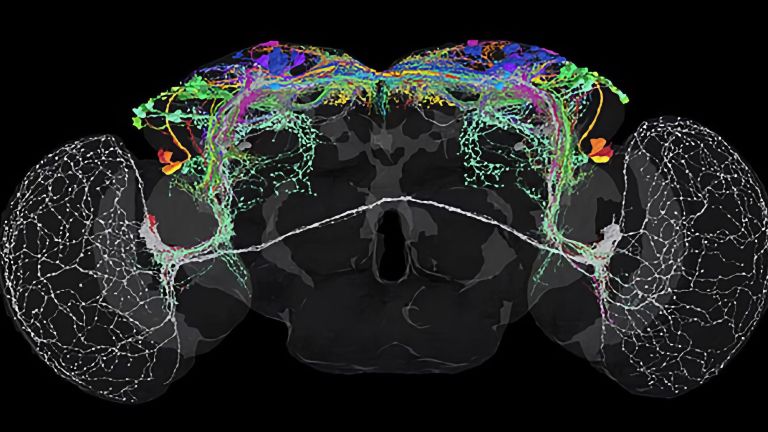

When investigating molecular and cellular learning mechanisms, the small size of the fly's brain also has a decisive advantage: “In mice, the cells and circuits that contribute to a particular behavior are so far apart that it is not possible to observe them at work simultaneously,” says André Fiala from the University of Göttingen. “In flies, on the other hand, we can look at the details of individual nerve cells with their synapses and at what is happening in the network at the same time.”

Recommended articles

Flexible neurons

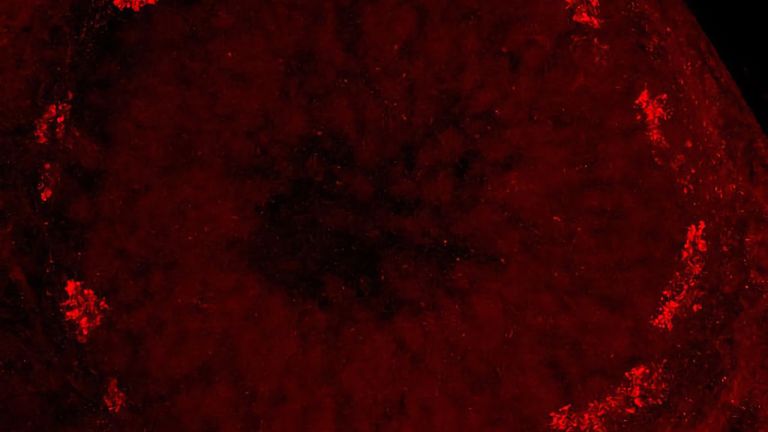

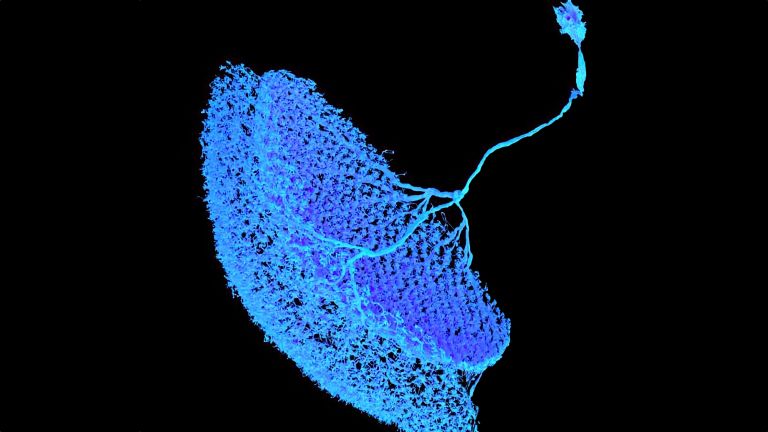

This shows that different synapses in the same cell are active to varying degrees depending on the odor – and that these activity patterns change when the fly learns to associate a scent with a negative stimulus, such as pain. The nerve cell passes these changes on to the neurons linked to the respective synapses, which now themselves respond differently to the stronger or weaker signals received at this synapse. What has been learned is thus fixed as a measurable memory trace. “It is interesting to note that memory is not encoded in whole cells, but in individual cell sections,” explains Fiala. His team is currently investigating how this section-by-section regulation of activity works at the molecular level. What changes at the level of molecules and circuits during complex learning processes?

There are many more unanswered questions about behavioral control that the mushroom bodies of the fly could help answer. For example, what changes when memory traces migrate from short-term to long-term memory? How exactly do you learn that certain foods were poisonous or spoiled if some time elapses between ingestion and unpleasant symptoms? How do learning processes in which a specific event is associated with a pleasant reward differ from those in which one “only” escapes an unpleasant situation? And what happens when aging or neurodegenerative diseases impair the function of cells and circuits involved in learning and memory?

With the help of Drosophila and a well-stocked molecular biology toolbox, answers can be found and translated into computer models that also allow predictions relevant to humans about how the spatiotemporal dynamics of molecules, cells, and networks in the brain affect learning processes and the control of behavior ▸ Fly brain in the computer. Such models could even be used in the field of artificial intelligence to enable machines to learn more effectively. It remains to be seen which findings from the world of flies will actually apply to humans.

To take what they have learned from flies to the next level, researchers also rely on other model organisms more closely related to humans, such as zebrafish and mice (see box “Which model organism is right for you?”), as well as studies with human cell cultures and tissue samples. Fortunately, there is no need for a human-fly hybrid creature like the one in Neumann's horror film to answer these questions.

Further reading

- Hales KG, Korey CA, Larracuente AM, Roberts DM. Genetics on the Fly: A Primer on the Drosophila Model System. Genetics. 2015 Nov;201(3):815-42. ( Full text )

- Bellen HJ, Tong C, Tsuda H. 100 years of Drosophila research and its impact on vertebrate neuroscience: a history lesson for the future. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010 Jul;11(7):514-22. ( Full text )

- Bilz, F., Geurten, B.R.H., Hancock, C.E., Widmann, A., and Fiala, A. (2020). Visualization of a distributed synaptic memory code in the Drosophila brain. Neuron, 106, 1–14. ( Full text )

- Fiala A, Kaun KR (2024). What do the mushroom bodies do for the insect brain? Twenty-five years of progress. Learn Mem. 2024 Jun 11;31(5):a053827. https://learnmem.cshlp.org/content/31/5/a053827

- Eric Wieschaus, Christiane Nüsslein-Volhard (2016). The Heidelberg Screen for Pattern Mutants of Drosophila: A Personal Account

- Berrak Ugur, Kuchuan Chen, Hugo J. Bellen (2016). Drosophila tools and assays for the study of human diseases

- A Complete Electron Microscopy Volume of the Brain of Adult Drosophila melanogaster