If I were a Zombie

We are all a bit like zombies. Much of what we do and perceive does not involve conscious thought. Christian Wolf finds this both frightening – and practical.

Scientific support: Prof. Dr. Georg Northoff

Published: 28.08.2013

Difficulty: intermediate

- Much of what we do, think, or perceive in life happens without our conscious awareness.

- Particularly well-rehearsed movements work better without conscious thought.

- Automated movements are based on what is known as procedural knowledge, a form of unconscious knowledge.

- Automated processes save time and energy.

- Unconscious processes can also be helpful when making decisions under certain circumstances. Intuitive decisions, for example, must be based on a great deal of experience in order to be good.

- Only a small portion of the visual information that bombards us reaches our consciousness.

In principle, it looks like you and me and doesn't behave much differently. If it cuts its finger, for example, it will cry out in pain like anyone else. But subjectively, it feels nothing at all. Because it has no consciousness. Zombies are not only found in horror movies, but also in thought experiments by philosophers.

They are mostly used as arguments against forms of philosophical materialism or physicalism. According to these positions, only material or physically describable things and events exist in the universe. According to Australian philosopher David Chalmers, proponents of these positions must ultimately assume that the existence of consciousness arises solely from the physical and functional description of a living being. The fact that zombies are conceivable, however, demonstrates that even a complete physical-functional description does not necessarily imply the existence of consciousness.

For the Austrian founder of psychoanalysis, Sigmund Freud (1856-1939), the unconscious is the fulcrum of his conception. Our consciousness is only the tip of the iceberg. Hidden in deeper layers is the unconscious, where the drives of the id, such as the sex drive, are concealed. From a psychoanalytical perspective, the unconscious does not simply encompass everything that is not conscious, but rather everything that is actively repressed by conscious thought. Freud saw the unconscious as a place for socially undesirable ideas, desires, and traumatic memories. Unconscious thoughts are not directly accessible to self-observation, but can be tapped into and interpreted through psychoanalysis, for example through free association or the interpretation of dreams.

Sometimes I feel like I'm on autopilot. I walk through the streets lost in thought and suddenly find myself at my front door. How did I get here, I wonder. Or I marvel at the rapid flow of words that pours out of my mouth without my conscious intervention. Much of what we do, think, or perceive in life happens without us– at least without our conscious awareness. Psychologists and brain researchers have clearly demonstrated this in recent decades. Unconscious processes often take over when our consciousness is overwhelmed or at least not very helpful. In such cases, we are a bit like zombies stumbling through the world in a daze.

I sometimes experience this when playing table tennis: when I don't think about it, the fastest rallies come easily, almost as if by themselves. If, for example, I were to ponder the angle at which I should hit the approaching ball, I would not only be too slow, but I would also feel a bit like the centipede in a fable by the ancient Greek poet Aesop: When asked by a frog how he coordinates his many legs, he inevitably loses his footing.

Consciousness hinders automated movement sequences

In fact, consciousness does more harm than good when it comes to well-rehearsed movement sequences. Psychological studies have shown that beginners improve when they consciously concentrate on the sequence of movements when learning a sport, for example. However, experts in a field perform worse when they pay attention to their movements. The same applies to playing an instrument. Conscious concentration on individual notes paralyzes pianists when playing fast, according to an example given by Canadian cognitive scientist Merlin Donald in his book “The Triumph of Consciousness.”

Well-practiced and automated movement sequences are based on what is known as procedural knowledge. This is created when a specific stimulus is linked to a specific response in the memory over time – unconsciously. For example, when I swing myself onto my bike, this triggers certain motor activities. This is implicit knowledge. You can do something without knowing exactly how you do it.

In his bestseller “Blink,” English science journalist Malcolm Gladwell reports on this phenomenon among top tennis players: they could never describe exactly what they do on the court outside of the tennis court. Many of their stories are simply not true. One world-class player claimed, for example, that he kept his eye on the ball right up until the moment he hit it. But according to Gladwell, this is impossible. “The ball is much too fast and too close: one and a half meters before the ball hits the racket, it disappears from the player's field of vision. The actual stroke is made blind.”

Advantages and disadvantages of unconscious processes

The advantages of automated processes are obvious: they save time and energy. I don't have to think too much about how to do something. What's more, I'm not subject to the capacity limitations of consciousness. Even though we would like to believe the opposite, studies on multitasking have proven that we cannot perform two processes that require consciousness at the same time. So, I can't listen to someone on the phone with full concentration and quickly type an error-free email at the same time. The brain's unconscious processing systems, on the other hand, can work in parallel.

Unfortunately, automated processes also have their shortcomings. They cannot be easily transferred to other tasks. The fact that I'm not bad at table tennis doesn't help me much when playing the piano. I'm pretty terrible at that.

Better to sleep on it?

Unconscious processes can also be helpful in some decisions. Conscious thinking is often overwhelmed when there is too much information and too many options available. Psychologists in magazines and on television therefore recommend that I “listen to my gut” or “sleep on it” when faced with complex decisions. Psychologist Ap Dijksterhuis, back then at Radboud University in Nijmegen, for example, advises reflecting unconsciously – while asleep, so to speak. In his experiments, the test subjects made the best purchasing decisions when they were distracted from consciously thinking about different options. So, if I want to invest the wealth I have accumulated from writing articles in my next house, should I rely on my subconscious instead of diligently gathering information about the property?

Better not. Some other psychologists warn against overestimating the capabilities of the subconscious. Take Ben Newell from the University of New South Wales in Sydney, for example: In his laboratory, conscious deliberators found it easier than unconscious deliberators to choose the best car from a selection. However, this was on condition that they were able to study the information about the different vehicles at their leisure and think about it for a long time. The type of decision and the circumstances determine which form of deliberation should be chosen, explains Newell in a 2009 essay. Sleeping on a decision overnight can indeed be useful. Putting things aside and coming back to them later allows us to look at the decision again with a fresh perspective. However, this does not mean that the subconscious can “magically” solve things for us.

Recommended articles

Should we listen to our gut feeling?

Even with the widely praised gut feeling, it's not quite that simple. Malcolm Gladwell recommends the technique of making quick and intuitive decisions in his book. As an example, he cites a fire lieutenant who decided in a split second to evacuate a building – just before the living room floor collapsed, where he and his men had been standing just moments before. The firefighter had unconsciously processed a lot of information, such as the fact that the fire was not responding to the water being used in the kitchen and that the living room was so hot. In fact, the source of the fire was in the basement below the kitchen. “At that point, of course, the lieutenant couldn't have described the connections in this way,” Gladwell says. “The thought process took place behind the closed door of his unconscious mind.”

At first, this sounds perfectly plausible to me. But in his essay, Ben Newell teaches me otherwise. Of course, there are cases where quick thinking is appropriate, says Newell. However, this is only true if intuition is based on sufficient experience in the relevant field – as in the case of the firefighter. Some quick decisions that appear to be intuitive are in fact the result of years of reflection and the conscious acquisition of information.

Consciousness as a user interface

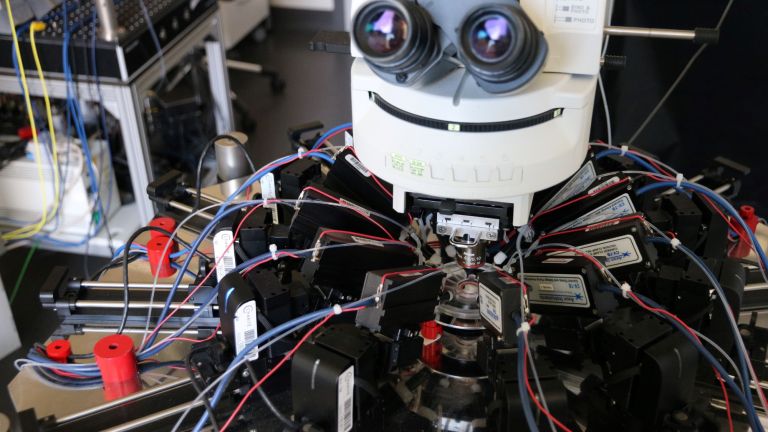

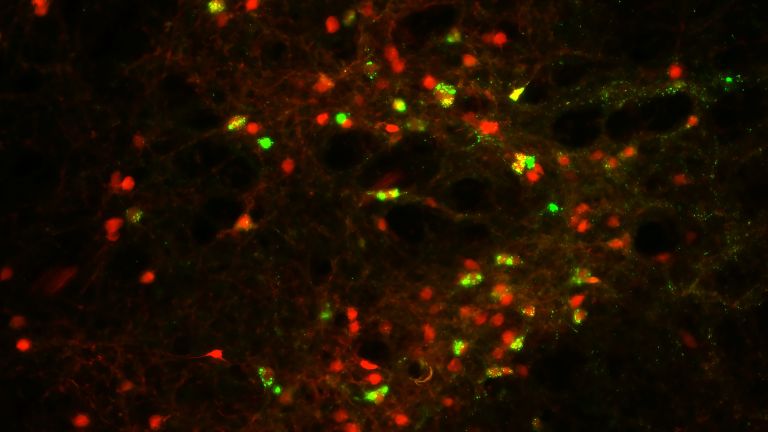

Despite these limitations, there is no question that unconscious processes play a major role in our decisions. And even in the case of perception, our conscious experience is only the tip of the iceberg. Not all the visual information that bombards me from my surroundings reaches my consciousness. If, for example, I were presented with a stimulus on a screen in a laboratory and then another one within a few milliseconds, I would not be aware of the first stimulus at all. My brain processes many stimuli – especially very short ones – without me noticing.

If the ideas of many scientists and philosophers are correct, then I experience only a simplified user interface, so to speak. In the background, my brain performs the complicated calculations. Not having full control sounds frightening, but it is also very practical. Just like with autopilot.

Further reading

- Newell, B.R. et al: Think, blink or sleep on it? The impact of modes of thought on complex decision making. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 2009; 62(4), pp. 702–732 (to the text).

First published on August 28, 2013

Last updated on June 13, 2025