Miniature Brains

Distinguishing scents at lightning speed or escaping nasty parasitic wasps: the comparatively simple nervous system of fruit flies is quite capable. And if necessary, they can even do without their heads.

Wissenschaftliche Betreuung: Prof. Dr. Björn Brembs

Veröffentlicht: 24.01.2026

Niveau: leicht

- Nur 250 Mikrometer lang ist das Gehirn der Fruchtfliege. Während das menschliche Gehirn 86 Milliarden Neurone umfasst, sind es nach Schätzungen im Fliegenhirn 100.000 bis 200.000.

- Das Gehirn von Fruchtfliegen ist unterschiedlich ausgestattet, je nachdem ob sich die Fliege noch im Larvenstadium befindet oder schon erwachsen ist.

- Das Zentralnervensystem der erwachsenen Fliege besteht aus einem Oberschlundganglion, einem Unterschlundganglion, einem ventralen Nervenstrang, und dem stomatogastrischen Nervensystem.

- Das Oberschlundganglion ist der größte Nervenknoten (Ganglion) des zentralen Nervensystems und wichtig für das Lernen. Es liegt über dem Schlund und entspricht in seiner Funktion etwa dem Gehirn bei Wirbeltieren.

- Die Netzhaut von Fruchtfliegen kann den so genannten e-Vektor von polarisiertem Licht ausmachen. Mit Hilfe des e-Vektors können die Fliegen sich an der Sonne orientieren.

- Fruchtfliegen können Luftströmungen wahrnehmen. Schwankungen in der Luftströmung am Geruchsorgan beeinflussen bei ihnen die Geruchswahrnehmung und helfen den Insekten möglicherweise, die Quelle von Gerüchen auszumachen.

- Mit Hilfe von chemosensorischen Rezeptoren der Antennen können Fruchtfliegen Kohlendioxid (CO2) wahrnehmen. CO2 ist einer der wichtigsten Geruchsstoffe, um Nahrungsquellen zu finden und Artgenossen zu warnen.

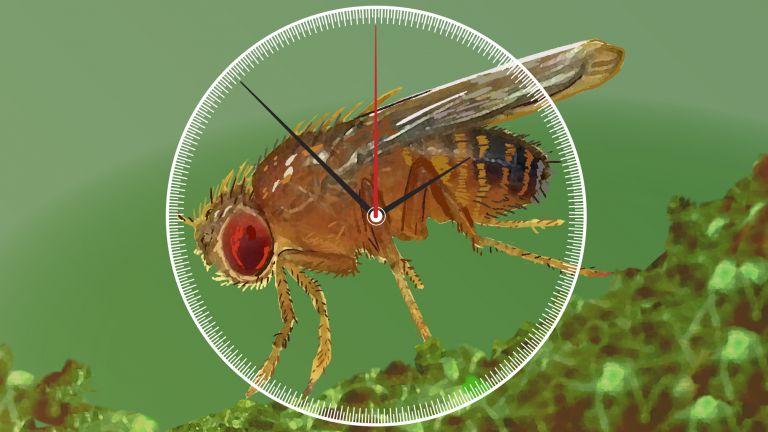

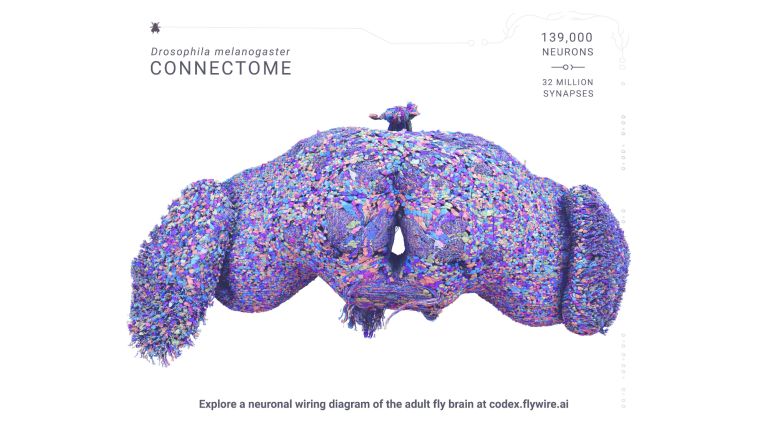

The fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster is a rather small creature, it usually grows to only two millimeters in size. And so, of course, its brain is also tiny; the side length is just a quarter of a millimeter, or 250 micrometers. The cell body of a typical neuron in the head of a fruit fly has a diameter of two to four micrometers. While the human brain contains 86 billion nerve cells, the fly brain was previously thought to contain 100,000 neurons, but more recent estimates suggest it could be 200,000.

What exactly the cells have to do depends on the stage of life the fruit fly is in. Is it still a larva or has it already transformed into a fly? "Despite having a relatively simple brain, the larva exhibits complex behavioral patterns," says neurobiologist Christian Klämbt from the University of Münster. "It doesn't have to find a mating partner, but it does need suitable food, of course." When the larva crawls through fruit pulp, it perceives its surroundings. Certain sensory cells trigger a specific escape response. This happens precisely when parasitic wasps approach, wanting to lay their fertilized eggs in the larvae.

From escape reflex to complex behavior

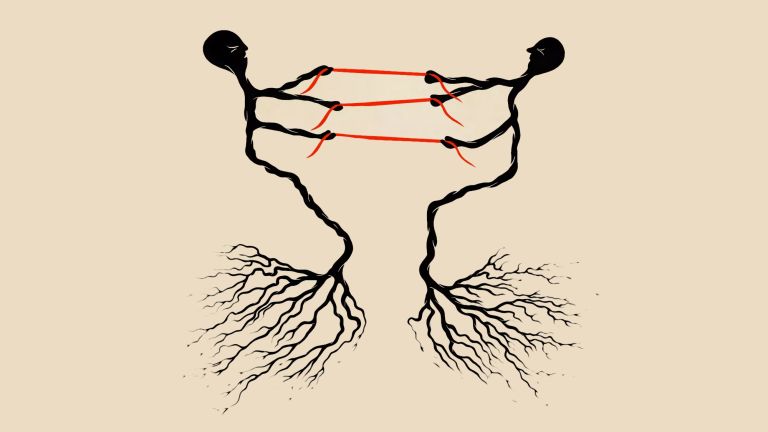

"When the larvae hear the wasp's wings beating and feel the sting on their skin, they roll sideways," reports Klämbt. This prevents the wasp from piercing the skin and injecting its egg into the larva. "The control of this escape reaction is hardwired into a simple circuit in the larva's brain," says Klämbt. An adult fly no longer exhibits this escape reflex. Instead, it simply flies away when threatened. "The neural circuits necessary in the larva are rebuilt during metamorphosis, and the neurons can be assigned to other tasks."

Larvae also have a memory and can learn. But unlike adult flies, the memory traces only need to be very short-lived, as the larval stages last only a few days. "The memory of the adult fly is more complex because it has to process significantly more sensory information," explains Klämbt. For example, the eyes are much larger, and the olfactory system is also more complex. The neural circuits that enable larvae to learn and store memories are somewhat simpler in structure than those of adult flies, but they work according to the same principles.

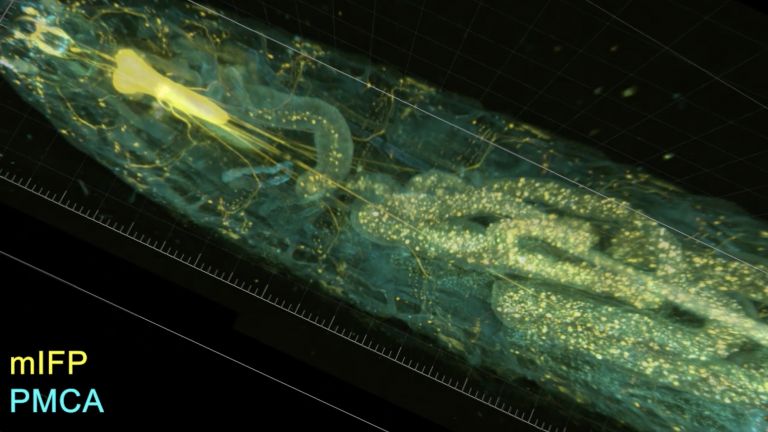

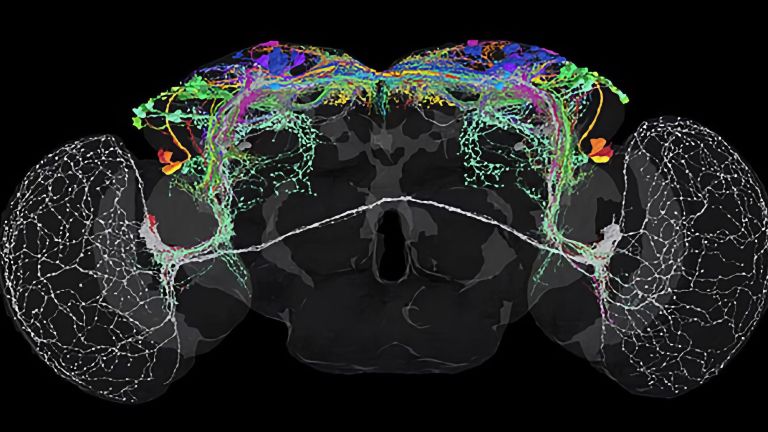

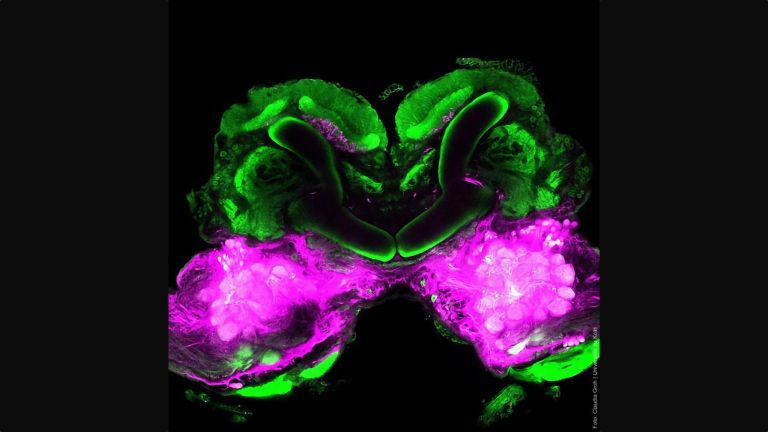

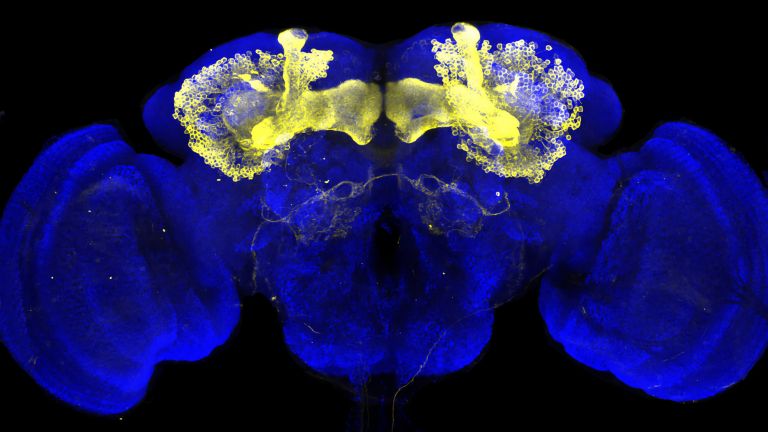

The central nervous system of the adult fly consists of a supraesophageal ganglion, a subesophageal ganglion, a ventral nerve cord, and the stomatogastric nervous system. The supraesophageal ganglion is the part of the central nervous system located above the esophagus, the largest nerve node (ganglion) of the central nervous system. Its function is similar to that of the brain in vertebrates and comprises three sections, including the protocerebrum. This is the processing center for all higher sensory functions and the decisive control center for most complex behaviors. The protocerebrum contains the two optic lobes, which are responsible for visual processing.

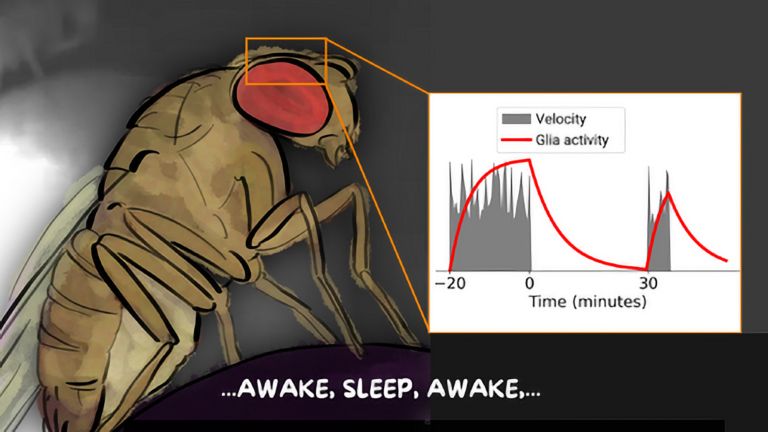

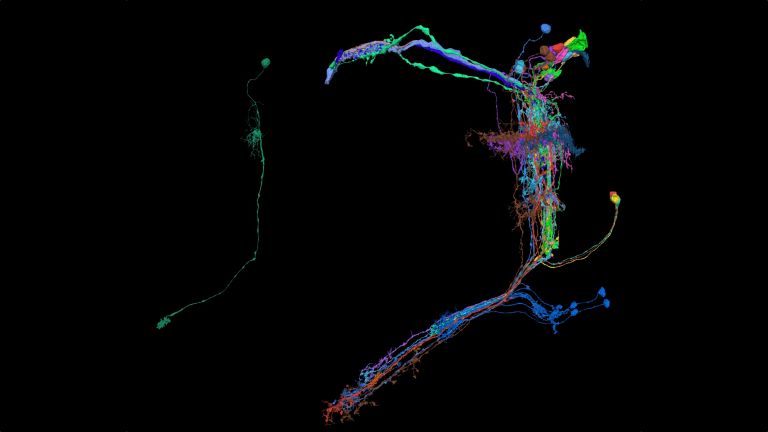

The protocerebrum is also the seat of the mushroom body, which is of particular importance for insects. "It has long been known that the mushroom body is important for scent learning," says physicist and neuroscientist Martin Nawrot from the University of Cologne. "What is new, however, is the realization that the mushroom body also plays a decisive role in translating sensory information into motor activity." This means that it is ultimately involved in deciding how an animal behaves. Sparse coding is very important for learning, especially "spatial sparsity," as Nawrot explains:

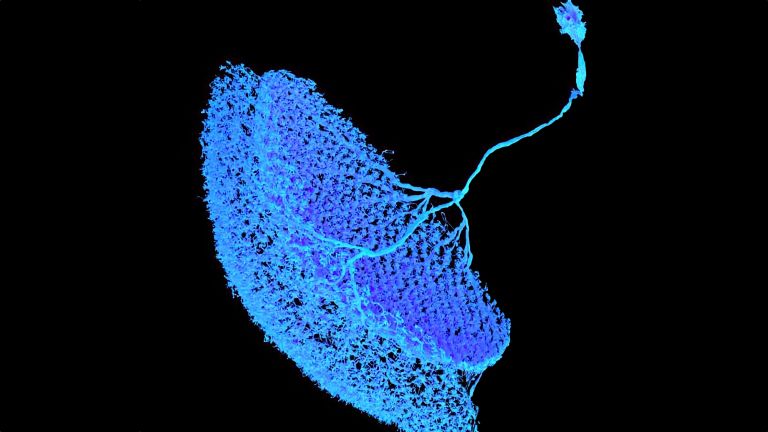

"The actual odor information is encoded in a few hundred neurons in the so-called antenna lobe, which all flash in response to the odor," says Nawrot. "This odor code is then projected into the mushroom body, where it encounters a total of 4,000 neurons, the Kenyon cells, but only a few of these become active for each odor." The Kenyon cells, which are important for learning smells, in turn form a large number of synapses with output neurons of the mushroom body. And these synapses change when, for example, a scent is followed by a reward such as sugar water. "Because certain subgroups of Kenyon cells are associated with a specific scent, individual scents can be learned very specifically and efficiently," says Nawrot.

Empfohlene Artikel

Distinguishing scents super fast

In addition to spatial sparsity, there is also temporal sparsity. While neurons in the antenna lobe need one to two seconds for scent coding, Kenyon cells are only active for around 50 to 100 milliseconds. And even then, only when the scent intensity changes, for example when the scent begins or becomes twice as strong. "This is an important adaptation to the environment," says Nawrot. When the fly flies through a cloud of scent, the individual scents in the cloud often only occur for 50 to 100 milliseconds. The Kenyon cells respond sparsely, with brief activity. It is sufficient for certain Kenyon cells to have responded once to a particular scent with an action potential in order to recognize it again after just 50 milliseconds the next time. This enables flies in nature to react very quickly to brief scent impressions and head straight for the right scent source, such as a banana. Martin Nawrot and his colleagues used a computer model to simulate how a fly flies through a cloud of scent. "Every scent pulse, no matter how short, that the animal encounters is recognized; an irrelevant scent, on the other hand, is ignored."

Acting headless

However, these small animals can also act headless in the truest sense of the word. Decapitated fruit flies can still walk and groom themselves. The reason for this is that the circuits of the so-called ventral nerve cord are sufficient to execute simple motor programs without brain control. Functionally, the ventral nerve cord corresponds to the spinal cord in vertebrates.

The only major component of the fruit fly's nervous system that is missing now is the stomatogastric nervous system. This is a system composed of ganglia and nerves. The parts of the stomatogastric nervous system are connected to both the brain and to each other. It supplies the oral cavity, foregut, and certain hormone glands. It is important for food intake and digestion.

As tiny as the fruit fly's nervous system is, it is certainly powerful. If necessary, even without a head.

Further reading

- Scheffer LK, Xu CS, Januszewski M, et al. A connectome and analysis of the adult Drosophila central brain. Elife. 2020;9:e57443 (full text). doi:10.7554/eLife.57443

- Raji JI, Potter CJ. The number of neurons in Drosophila and mosquito brains. PLoS One. 2021;16(5):e0250381 (full text). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0250381

- Fiala A, Kaun KR (2024). What do the mushroom bodies do for the insect brain? Twenty-five years of progress. Learn Mem. 2024 Jun 11;31(5):a053827. https://learnmem.cshlp.org/content/31/5/a053827

- Rapp H, Nawrot MP. A spiking neural program for sensorimotor control during foraging in flying insects. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117(45):28412-28421 (full text). doi:10.1073/pnas.2009821117