Flies? Why flies?

Flies and humans are worlds apart. However, if you look at the brain and the genome of this tiny insect, you will see that many things work in a very similar way.

Wissenschaftliche Betreuung: Prof. Dr. Martin Göpfert

Veröffentlicht: 17.01.2026

Niveau: leicht

- Die Taufliege Drosophila ist der Superstar unter den Versuchstieren: klein, pflegeleicht und vermehrungsfreudig. Eine neue Fliegengeneration wächst in nur 10 Tagen heran.

- Viele heute bekannte Gene wurden zuerst in Taufliegen entdeckt. Das funktioniert in Reihenuntersuchungen, in denen man zum Beispiel genetische Mutationen hervorruft und dann in den Insekten nach veränderten Eigenschaften sucht und diese beschreibt. Sehr viele der so gefundenen Gene kommen in ähnlicher Form auch im Menschen vor und arbeiten auch in unserem Körper ganz ähnlich.

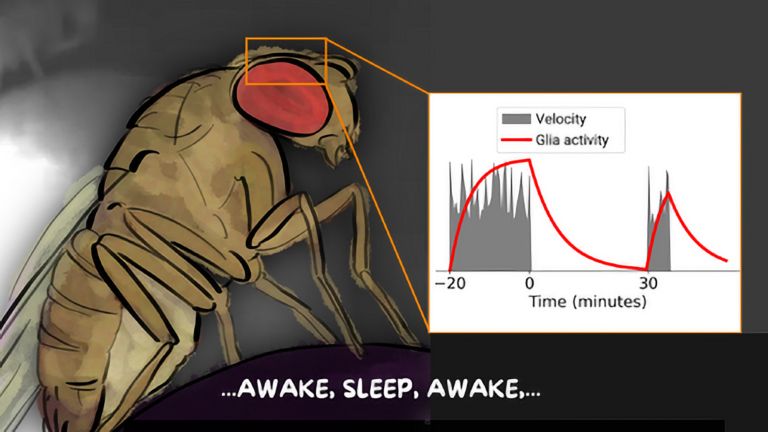

- Auch die Struktur und Funktion von Nervenzellen und selbst der Aufbau von neuronalen Netzwerken ähneln sich im Menschen und in der Fliege. Und da Fliegen einiges lernen und sich vielfältig verhalten können, lassen sich auch neurowissenschaftliche Fragen gut an ihnen untersuchen.

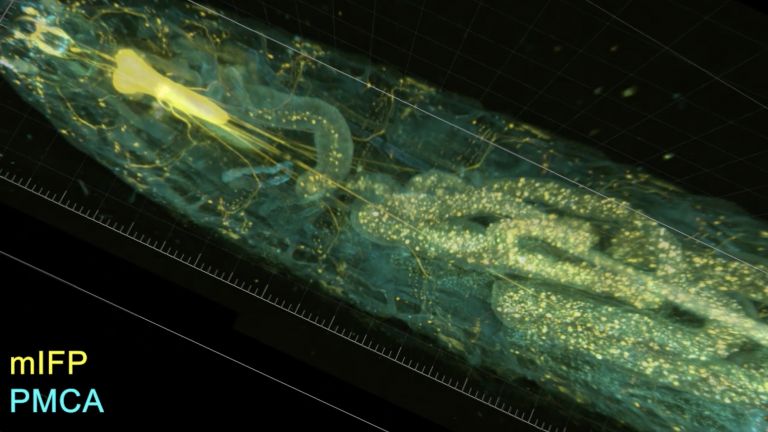

- Taufliegen sind experimentell besonders gut zugänglich. Ihre Gene lassen sich in einzelnen Gewebe- oder Zelltypen gezielt aktivieren, blockieren oder in ihrer Funktion verändern. Auch die Aktivität einzelner Zellen oder Moleküle lässt sich im lebenden Tier gut manipulieren und beobachten. Fliegen eignen sich daher gut für die Untersuchung molekularer und zellulärer Mechanismen.

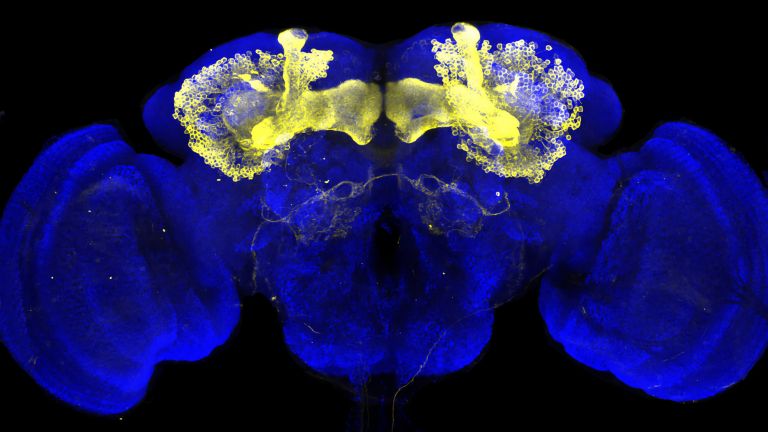

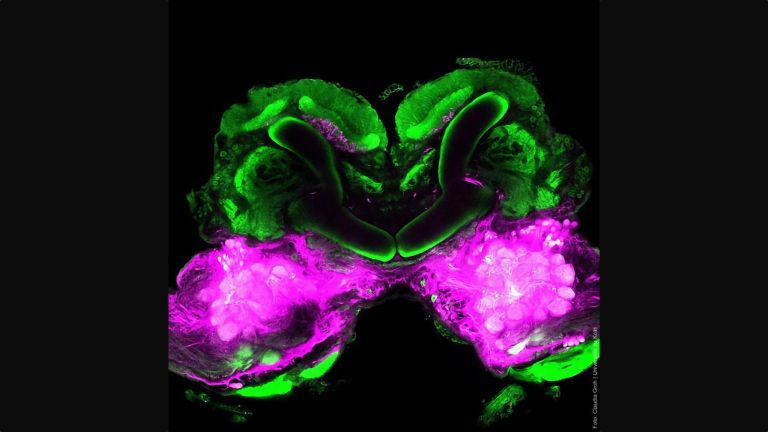

- Im Gehirn der Fliege vereint der Pilzkörper auf kompaktem Raum wichtige Funktionen, die im menschlichen Gehirn auf unterschiedliche Regionen verteilt sind: die Integration von Sinneseindrücken, die Bildung und Speicherung von Erinnerungen und eine Entscheidungszentrale zur Verhaltenssteuerung. Im Pilzkörper lässt sich daher besonders gut integrativ untersuchen, wie Moleküle, Nervenzellen und Netzwerke zusammenwirken, um situations- und erfahrungsabhängiges Verhalten hervorzubringen.

Die Liste der experimentellen Tricks, mit denen Drosophila melanogaster untersucht werden kann, ist lang und wächst ständig. Hier eine Auswahl der beliebtesten Techniken:

- Genetischer Screen Fliegen werden genetisch gezielt manipuliert und ihre Nachkommen über mehrere Generationen auf veränderte Eigenschaften untersucht. Dank besonders stabiler Vererbung und zahlreichen Markierungsmöglichkeiten (zum Beispiel Augenfarbe) kann man die gefundenen Veränderungen bestimmten Chromosomen, Chromosomenregionen und ganz genauen Genregionen zuordnen. Dies ist möglich, weil für Drosophila melanogaster – als erstes Tier überhaupt – das komplette Genom genau aufgeschlüsselt wurde.

- Gewebespezifische Genexpression Mit der Entdeckung von Transposons – Genabschnitten, die Proteine herstellen, mit denen sie sich selbst ausschneiden und an anderer Stelle im Genom wieder einfügen können – wurde es möglich, das Fliegengenom gezielt zu verändern. In einer beliebten Variante erhält eine Fliegengruppe ein Gen, dessen Protein die Transkription anderer Gene aktivieren kann, gekoppelt mit einer DNA-Sequenz, die nur in bestimmten Geweben zugänglich ist. Eine andere Gruppe von Fliegen erhält ein Gen, dessen Transkription von dem Aktivator der ersten Gruppe angeregt wird. Kreuzt man die beiden Gruppen entstehen Fliegen, in denen die Transkription des zweiten Gens nur in dem in der ersten Gruppe ausgewählten Gewebe aktiviert wird. So kann man ganz gezielt bestimmte Gene in ausgewählten Zellen, wie zum Beispiel ganz genau definierten Nervenzellen, zur Expression bringen.

- Gezielte Genveränderung Will man testen, ob ein bereits bekanntes Gen eine Rolle in bestimmten Prozessen spielt, kann man seine Funktion mit verschiedenen Methoden gezielt verändern und dann untersuchen, was in dem jeweiligen Prozess passiert. Die Veränderungen gelingt zum Beispiel mit der „Genschere“ CRISPR/Cas9 oder mit RNA-Interferenz, bei der das Gen selbst unverändert bleibt, aber die von ihm transkribierte RNA deaktiviert wird.

- Optogenetik Hier wird eine Nervenzelle oder Gruppen von Nervenzellen mit einem „Schalter“ versehen, der aus einem transgen exprimierten, lichtempfindlichen Protein besteht. Das Ergebnis ist ein lichtempfindlicher Ionenkanal der sich mit einem Lichtreiz schnell und vorübergehend aktivieren oder deaktivieren lässt. In der Folge knipst der Schalter die zugehörigen Nervenzellen durch Licht an- und aus.

Die Techniken lassen sich miteinander kombinieren.

Die Taufliege ist nicht das einzige Tier, mit dessen Hilfe sich spannende neurowissenschaftliche Fragen untersuchen lassen. Die Konkurrenz kommt mit jeweils eigenen Stärken und Schwächen:

- Der Wurm Caenorhabditis elegans bedeutet „eleganter neuer Stab“ – ein hochtrabender Name für den nur einen Millimeter kleinen Fadenwurm. Die Würmer sind sehr pflegeleicht, molekulargenetisch gut untersuchbar und manipulierbar, lassen sich sogar einfrieren und verfügen über eine exakte Zahl von Zellen mit von Anfang an genau festgelegten Schicksalen. Mit maximal 385 Neuronen ist das Nervensystem des Wurms sehr überschaubar – sein Verhaltensrepertoire aber auch.

- Die Meeresschnecke Aplysia californica heißt auf Deutsch „Kalifornischer Seehase“ und ist auch ungefähr so groß wie seine landlebenden Namensvetter. Seehasen haben besonders große Nervenzellen und ein einfach aufgebautes Nervensystem. Elektrophysiologische Untersuchungen klappen so bestens, und Nobelpreisträger Eric Kandel nutzte dies, um den Schnecken die zellulären und molekularen Grundlagen des Lernens zu entlocken. Molekulargenetische Werkzeuge gibt es hingegen eher wenige.

- Der Fisch Der Zebrafisch Danio rerio ist die Taufliege unter den Wirbeltieren. Auch dieser Modellorganismus kommt mit einem prall gefüllten molekularbiologischen Werkzeugkasten; Aufwand und Zeitbedarf pro Generation sind aber wesentlich größer als bei Drosophila. Zebrafische legen hunderte von durchsichtigen Eiern, in denen innerhalb von 24 Stunden eine Fischlarve heranwächst. Die gesamte Entwicklung des Fischleins lässt sich prima unter dem Mikroskop beobachten und auch für komplexere verhaltensbiologische Studien eignet Danio rerio sich gut.

- Die Maus Viele molekularbiologische und genetische Werkzeuge lassen sich auch bei Mäusen anwenden. Als Säugetiere sind sie uns Menschen deutlich ähnlicher als die meisten anderen Modellorganismen und versprechen so Forschungsergebnisse, die mehr mit dem Menschen zu tun haben, gerade auch, wenn es um komplexes Verhalten geht. Die Ähnlichkeit mit dem Menschen erschwert aber auch viele Untersuchungen. Die Entwicklung dauert länger und findet schwer zugänglich im Mutterleib statt. Aufgrund ihrer großen Empfindsamkeit gibt es zudem höhere Anforderungen an den Tierschutz

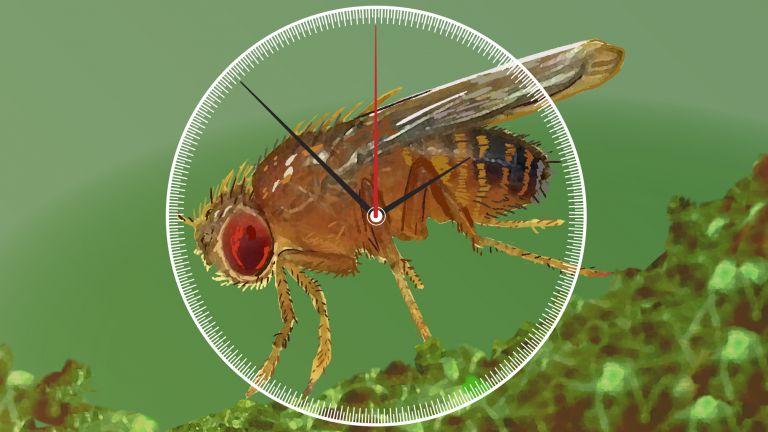

In Kurt Neumann's 1958 horror film The Fly, terrible things happen to a researcher after his body is accidentally fused with that of a fly in an experiment. In contrast, real research, which has revolved around the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster in many disciplines for more than 100 years, has so far remained free of gruesome side effects. However, reality is hardly inferior to the film in terms of vision: the small insect, also known to many as the fruit fly or vinegar fly, is expected to answer big questions and has already done so: How does a complex body grow from a fertilized egg cell? How do diseases develop? How does the brain learn?

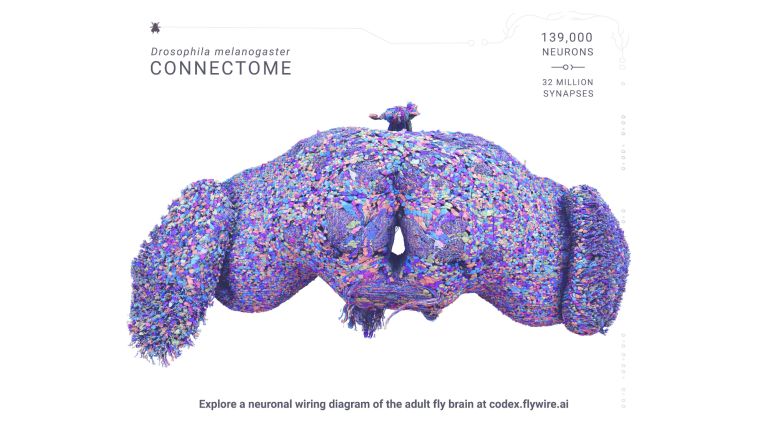

The last question in particular seems presumptuous. Only 100,000 neurons work in the Drosophila brain; in humans, 86 billion nerve cells are clustered together, almost ten thousand times as many. But what we know about the fly so far makes it clear that the modest fly brain can teach us a lot about learning. It is not without reason that Drosophila is the favorite laboratory animal in research. As early as 1910, the American zoologist and geneticist Thomas Hunt Morgan appreciated the advantages of the little fly for his pioneering work in genetics, for which he later received the Nobel Prize. Fruit flies are small, easy to care for, extremely fertile, and reproduce quickly.

A generation takes just ten days. In their “fly room,” a laboratory measuring just 35 square meters, Morgan and his team initially needed little more than ripe bananas, milk bottles, and magnifying glasses to observe how certain characteristics were passed on from generation to generation in thousands of flies.

It's all in the genes

It quickly became clear that flies were a stroke of luck for biological research in many other ways. The animals are extremely easy to study and manipulate, both genetically and in terms of cell and molecular biology (see box “The molecular genetics toolbox”). Morgan and many others who soon followed in his footsteps initially unlocked the secrets of Drosophila by exposing the animals to mutating X-rays or chemicals. They then studied the effects of these mutations in painstaking detail using so-called screens and assigned them to specific positions on the chromosomes.

Christiane Nüsslein-Volhard and Eric Wieschaus used this method in 1980 to characterize 600 mutations in 120 genes that alter the segment pattern of fly larvae – work for which they later also received the Nobel Prize. In doing so, they deciphered crucial mechanisms of embryonic development. And, as it later turned out, these genes also orchestrate development in many other animals, including humans, and are involved in disease processes – including in the nervous system.

The surprising similarity between fruit flies and other organisms that are only very distantly related to them has since been confirmed time and again. In 2000, the fly's genome was completely decoded; and a few months later, in 2001, the first, not yet complete sequencing of the human genome was published. Since then, it has become clear that many human genes have corresponding counterparts with similar structures and/or functions in the fly. This applies, for example, to 77 percent of the disease-relevant human genes known in 2001. The list is constantly updated in an online database called “Flybase.”

Highly capable of learning

The fly's brain is also more similar to the human brain than one might initially assume. Although it is only the size of a poppy seed, it accomplishes a great deal in this small space. For example, flies have a very good sense of smell and sight and constantly compare this and other sensory information with further details in order to make decisions, navigate through three-dimensional space, find food, avoid dangers, and charm or fight other flies. ▸ Smart flies

Only those who are capable of learning can develop such a complex behavioral repertoire. Flies learn, draw on memories, and forget some things, just like humans. Even though the everyday lives of Drosophila melanogaster and Homo sapiens are worlds apart, the basic challenges of survival are so similar at their core that proven learning mechanisms have been preserved throughout evolution ▸ Learning on a pinhead – just like the genes involved. As early as the 1960s and 1970s, US researcher Seymour Benzer discovered genes that affect the learning ability of flies. Genes with the evocative names dunce and rutabaga, for example, encode the blueprint for enzymes that play an important role in intracellular signaling cascades, which are essential for learning processes. Since then, researchers have identified human counterparts for these and many other neurobiologically relevant fly genes.

There are therefore fundamental similarities between Drosophila melanogaster and Homo sapiens. This makes it possible to use studies on flies to discover details relevant to humans about how experiences and learning processes, but also diseases, change the neural circuits that control behavior.

Fly research at the forefront

The fruit fly makes it easy for researchers to examine it experimentally and pursue questions that are difficult or impossible to investigate in humans or other laboratory animals. Experimental techniques for specifically manipulating the fly's genome have been around since the 1980s and are constantly being refined. Specific genes or gene segments can be selectively activated, blocked, or altered in their function in individual tissue or cell types, including through the addition of transgenes, i.e., gene segments from other species. Such changes can be permanent or designed to be switched on and off by specific signals.

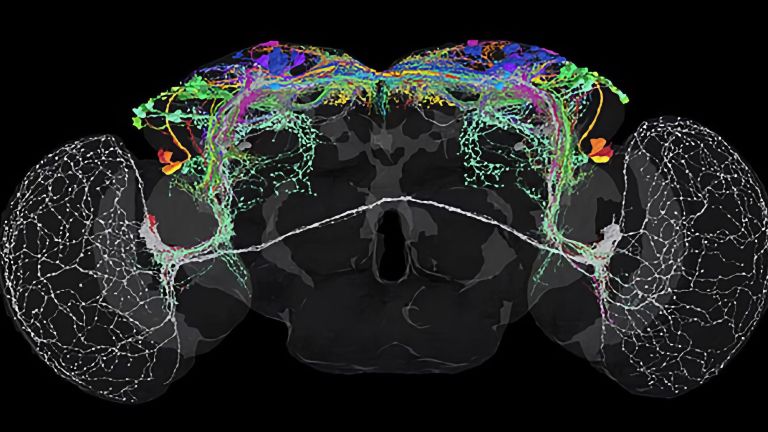

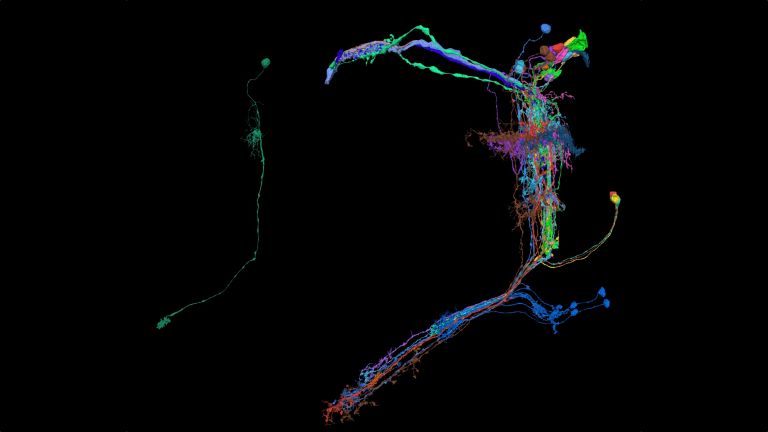

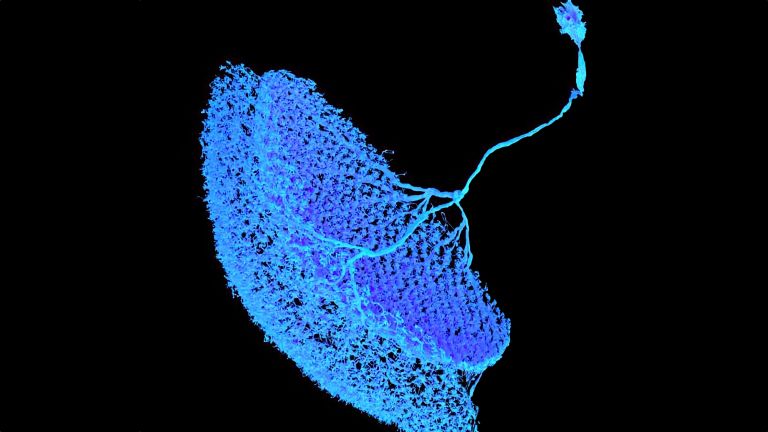

When investigating molecular and cellular learning mechanisms, the small size of the fly's brain also has a decisive advantage: “In mice, the cells and circuits that contribute to a particular behavior are so far apart that it is not possible to observe them at work simultaneously,” says André Fiala from the University of Göttingen. “In flies, on the other hand, we can look at the details of individual nerve cells with their synapses and at what is happening in the network at the same time.”

Empfohlene Artikel

Flexible neurons

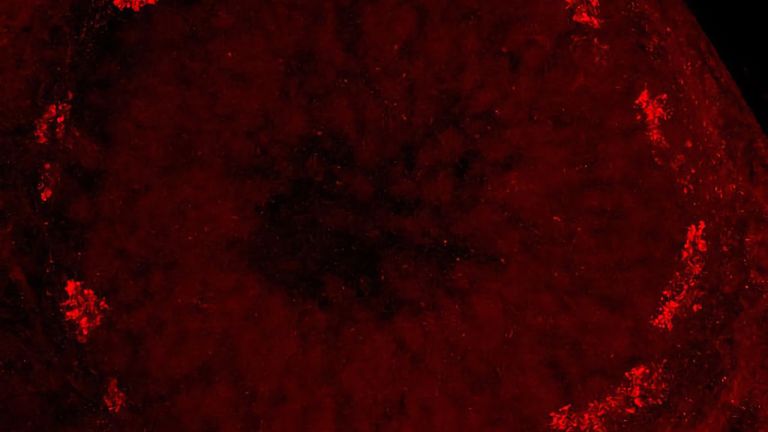

This shows that different synapses in the same cell are active to varying degrees depending on the odor – and that these activity patterns change when the fly learns to associate a scent with a negative stimulus, such as pain. The nerve cell passes these changes on to the neurons linked to the respective synapses, which now themselves respond differently to the stronger or weaker signals received at this synapse. What has been learned is thus fixed as a measurable memory trace. “It is interesting to note that memory is not encoded in whole cells, but in individual cell sections,” explains Fiala. His team is currently investigating how this section-by-section regulation of activity works at the molecular level. What changes at the level of molecules and circuits during complex learning processes?

There are many more unanswered questions about behavioral control that the mushroom bodies of the fly could help answer. For example, what changes when memory traces migrate from short-term to long-term memory? How exactly do you learn that certain foods were poisonous or spoiled if some time elapses between ingestion and unpleasant symptoms? How do learning processes in which a specific event is associated with a pleasant reward differ from those in which one “only” escapes an unpleasant situation? And what happens when aging or neurodegenerative diseases impair the function of cells and circuits involved in learning and memory?

With the help of Drosophila and a well-stocked molecular biology toolbox, answers can be found and translated into computer models that also allow predictions relevant to humans about how the spatiotemporal dynamics of molecules, cells, and networks in the brain affect learning processes and the control of behavior ▸ Fly brain in the computer. Such models could even be used in the field of artificial intelligence to enable machines to learn more effectively. It remains to be seen which findings from the world of flies will actually apply to humans.

To take what they have learned from flies to the next level, researchers also rely on other model organisms more closely related to humans, such as zebrafish and mice (see box “Which model organism is right for you?”), as well as studies with human cell cultures and tissue samples. Fortunately, there is no need for a human-fly hybrid creature like the one in Neumann's horror film to answer these questions.

Further reading

- Hales KG, Korey CA, Larracuente AM, Roberts DM. Genetics on the Fly: A Primer on the Drosophila Model System. Genetics. 2015 Nov;201(3):815-42. ( Full text )

- Bellen HJ, Tong C, Tsuda H. 100 years of Drosophila research and its impact on vertebrate neuroscience: a history lesson for the future. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010 Jul;11(7):514-22. ( Full text )

- Bilz, F., Geurten, B.R.H., Hancock, C.E., Widmann, A., and Fiala, A. (2020). Visualization of a distributed synaptic memory code in the Drosophila brain. Neuron, 106, 1–14. ( Full text )

- Fiala A, Kaun KR (2024). What do the mushroom bodies do for the insect brain? Twenty-five years of progress. Learn Mem. 2024 Jun 11;31(5):a053827. https://learnmem.cshlp.org/content/31/5/a053827

- Eric Wieschaus, Christiane Nüsslein-Volhard (2016). The Heidelberg Screen for Pattern Mutants of Drosophila: A Personal Account

- Berrak Ugur, Kuchuan Chen, Hugo J. Bellen (2016). Drosophila tools and assays for the study of human diseases

- A Complete Electron Microscopy Volume of the Brain of Adult Drosophila melanogaster