Traumatic Brain Injury

An average woodpecker's skull hits the tree at a speed of 25 km/h. Twenty times per second and, during courtship, as many as 12,000 times per day. Each peck exerts a force of 1,200 to 1,400 g. This has worked well for woodpeckers for 25 million years because, over the course of evolution, they have developed impressive shock absorbers for their brains.

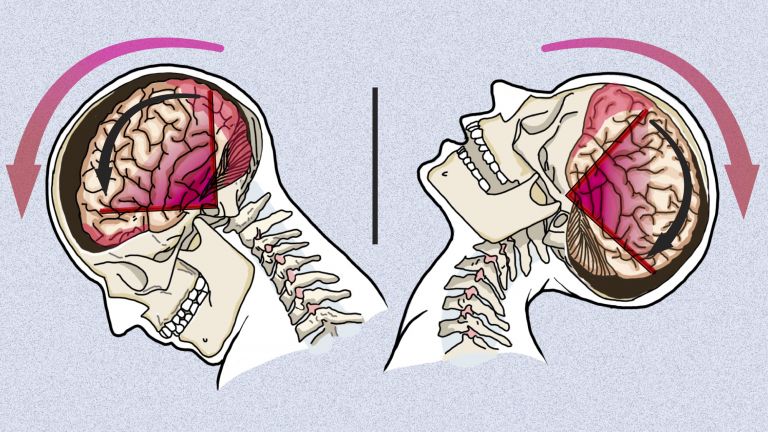

Other creatures also bump their heads. Accidentally their own, but animals such as bighorn sheep and musk oxen, or even Homo sapiens, deliberately bump the heads of others. In humans, this often occurs in "sports" such as boxing or American football. Contrary to the assessment of coaches and fans, the consequences are far less harmless than long thought. It is primarily the frequency, the sum total, that makes the difference between a concussion and a full-blown traumatic injury with subsequent dementia.

Big sports always mean big money. That's why the US National Football League reacted extremely late – not least because of the filmConcussionstarring Will Smith. Europe tends to play soccer. It's less dangerous, but by no means harmless. Some national soccer associations have therefore already banned header training for young people, but in general the danger is often ignored. Some players were back on the field 10 minutes after the blackout – and that is extremely dangerous.

This makes the issue all the more important to us, ranging from concussions and traumatic brain injuries to chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), also known as boxer's syndrome. Humans are not woodpeckers. And even in woodpeckers, a small study by researchers at Boston University School of Medicine in 2018 found an accumulation of tau proteins, which are typical of dementia.

Janosch Deeg provides an introduction to this topic in his article Damaged Athletes' Brains.