A human model of the blood-brain barrier

The brain is a special organ in our body and therefore particularly worthy of protection. With this in mind, the blood-brain barrier prevents potentially harmful substances from entering the brain from the bloodstream. Disruptions to this protective barrier contribute to the development of serious brain diseases such as stroke and Alzheimer's. Now, scientists at LMU Hospital in Munich led by Prof. Dr. Dominik Paquet and Prof. Dr. Martin Dichgans from the Institute for Stroke and Dementia Research (ISD) have succeeded in constructing a functioning human blood-brain barrier from human stem cells in the laboratory – and thus investigating disease processes. The results of the scientists, with first authors Dr. Judit González Gallego and Dr. Katalin Todorov-Voelgyi, were published in the renowned journal Nature Neuroscience.

Veröffentlicht: 16.12.2025

In recent decades, hundreds of drug compounds have shown such promise in animal experiments that they have also been tested in humans in extensive studies, for example against Alzheimer's dementia. However, only one has made it through and ultimately been approved for the treatment of patients. This modest success rate alone demonstrates how urgently drug development needs experimental models based on human cells that better reflect the effects and risks of potential new active ingredients. In addition, basic scientists at research institutions also rely on realistic models to decipher the genetic and molecular basis of brain diseases such as Parkinson's, Alzheimer's, or stroke.

One of the open questions, for example, is what role disturbances of the blood-brain barrier play in neurological diseases. This is a complex system of several cell types, primarily endothelial cells in the innermost layer of blood vessel walls, but also smooth muscle and glial cells. On the one hand, they form an almost impenetrable passive barrier and, on the other hand, they also actively ensure that substances important for the brain are allowed to pass through and potentially dangerous substances are excluded from the blood. “This barrier creates a very specific environment in the brain, without which the nerve cells would not be able to function properly,” explains Prof. Dr. Dominik Paquet, Professor of Neurobiology at the Institute for Stroke and Dementia Research (ISD) at LMU Hospital in Munich.

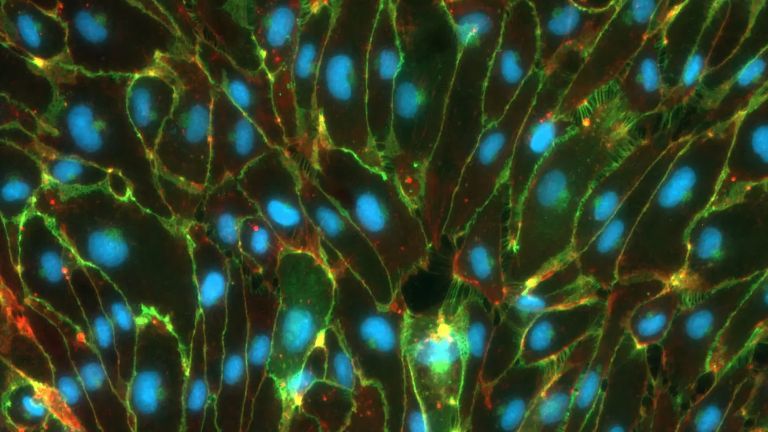

In 2018, his team began to recreate a model of the blood-brain barrier in the laboratory. This is based on so-called induced pluripotent stem cells (iPS) from humans. The experts at the Institute for Stroke and Dementia Research (ISD) used these to produce all the cell types necessary for a blood-brain barrier. Using a few tricks from molecular and cell biology, the researchers then managed to get these cells to form a functioning three-dimensional tissue in a gel-like matrix, which looks very similar to the blood vessels in the brain in microscopic images. “In close collaboration with Martin Dichgans' lab, we were also able to show that disease processes can be studied in this model,” Paquet continues. “For example, we have found that the blood-brain barrier no longer functions properly when a so-called risk gene, which frequently occurs in stroke patients, is altered in the endothelial cells,” says Prof. Dr. Martin Dichgans, Director of the Institute for Stroke and Dementia Research (ISD).

The experimental system is now available to scientists worldwide who want to investigate research questions related to the blood-brain barrier. “The system can be quickly established in any laboratory within a few weeks,” says Paquet. He hopes that the development of new therapies for neurological diseases will be accelerated with the model from Munich.

Original publication

González-Gallego, J., Todorov-Völgyi, K., Müller, S.A. et al. A fully iPS-cell-derived 3D model of the human blood–brain barrier for exploring neurovascular disease mechanisms and therapeutic interventions; Nature Neuroscience (2025).

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-025-02123-w