“A kind of inflammatory slurry behind a closed curtain”

Inflammatory and neurodegenerative processes go hand in hand in MS, says neurologist Jürg Kesselring. In this interview, he explains how this finding could be used therapeutically.

Published: 09.07.2025

Difficulty: intermediate

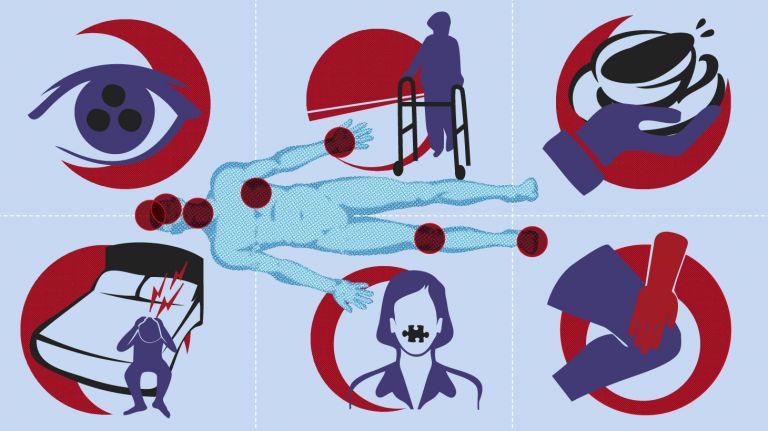

- For a long time, multiple sclerosis was thought to involve two independent chains of events: In the early stages, when MS occurs in episodes, inflammatory processes determine the course of the disease. In later stages, when the disease can progress, the degeneration of nerve cells prevails.

- However, based on current knowledge, the two processes cannot be strictly separated. Inflammation and neurodegeneration occur in parallel. Inflammatory processes clearly dominate in the early stages of MS. Although these processes subside in later stages, they continue to have a damaging effect.

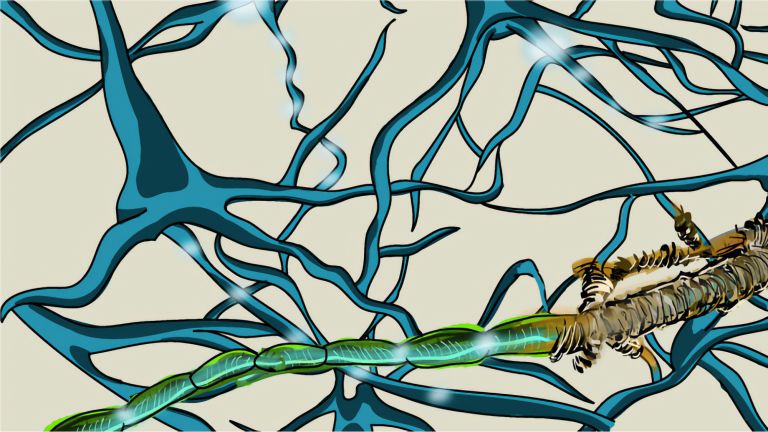

- In the early stages, immune cells from the periphery penetrate the blood-brain barrier and enter the brain, including inflammatory cells that scrape the myelin sheaths from the axons. This causes the nerve cells to degenerate.

- In later chronic phases, such inflammation continues to occur, but behind a blood-brain barrier that is once again intact.

- According to the latest findings, metabolic processes are also involved in the progressive degeneration of nerve cells. The mitochondria no longer adequately fulfill their function as energy suppliers to the cells.

Jürg Kesselring is a Swiss neurologist. Until his retirement in June 2025, he worked as chief physician for neurology and rehabilitation at the rehabilitation center in Valens. The trained physician has written specialist books on multiple sclerosis and rehabilitation.

Recommended articles

Prof. Kesselring, for a long time, multiple sclerosis was thought to involve two independent chains of events: inflammatory processes would transition into neurodegenerative processes. What do you think of this approach?

It was indeed believed that inflammatory processes and neurodegeneration could be strictly separated from each other. In the early stages, when MS occurs in episodes, inflammatory processes were thought to determine the course of the disease. In later stages, when the disease progresses, the degeneration of nerve cells was thought to predominate. This theory was based, among other things, on the fact that anti-inflammatory therapies are not very effective in advanced stages. However, a strict separation of immune response and neurodegeneration is probably neither possible nor sensible.

Why do you hold this view?

Professor Hans Lassmann, now emeritus professor of pathology at the Medical University of Vienna, and his colleagues, have, in my opinion, very impressively demonstrated that inflammation and neurodegeneration occur in parallel. According to current knowledge, it appears that inflammatory processes dominate in the early stages of MS and, although they decline in later stages, they still have a damaging effect.

Let's stick with this early phase for now. Can you describe it in more detail?

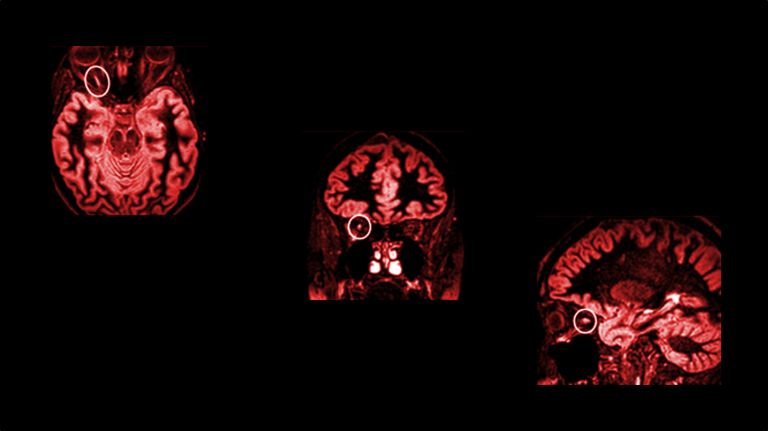

Normally, the blood-brain barrier separates the bloodstream from the brain and ensures that no foreign substances, pathogens, or toxic metabolites enter the brain. The barrier is therefore normally impermeable. In MS patients, however, it is open. This can be seen when a contrast agent injected into the patient's blood reaches the brain and can be visualized on an MRI scan. This can be observed very early on in those affected. The mechanisms that lead to the opening are not yet known in detail. However, the effect is clear: immune cells from the periphery penetrate the brain. This has been well documented for inflammatory cells such as T cells. In addition, other inflammatory cells such as macrophages are also found in the brain. As part of the inflammatory process, these can scrape away the myelin sheaths, the electrical insulation, from the axons – a process known as demyelination.

What effect does this have?

You can think of it like a tree. Without the bark, the tree trunk, or nerve extension, remains intact at first, but it will degenerate because it is no longer properly nourished. This, in turn, could lead to further inflammatory reactions, which are intended to remove the debris from the damaged nerve cells, but also further advance the disease.

And what happens in the later, chronic phases of MS?

Lassmann's team has described very impressively that inflammatory reactions continue to play a role even in chronic MS cases. The difference in these later stages of MS, however, is that the inflammation takes place behind a blood-brain barrier that has been restored, as the barrier repairs itself within four to six weeks after acute attacks.

Could the closed barrier be one reason why MS is more difficult to treat in the late stages than in the early stages?

As I understand it, this could indeed explain why anti-inflammatory drugs, which work quite well in the relapsing phase of MS, have little effect in the chronic form. My colleagues and I suspect that the drugs ultimately do not penetrate the blood-brain barrier into the areas of inflammation that are still present in the brain. Behind the closed curtain, there is a kind of inflammatory slurry that is probably composed of cells similar to those in the early phase.

Hans Lassmann and his colleagues also believe that in the later phases, a failure of the mitochondria, the powerhouses of the cells, contributes to the death of neurons.

Yes, exactly. This is a new branch of research that is certainly very interesting. However, I am not familiar enough with it. I am a clinician myself, but I am naturally interested in the findings of pathologists so that I can provide better care for my patients. However, we recently made a discovery that fits in with these findings. We were able to detect signs of spasmodic constriction of the blood vessels in our MS patients. This could explain why some patients complain of cold hands and feet. The role of metabolism in MS will certainly have to be investigated in more detail in the future.

Are there already ideas on how these new findings could be used therapeutically?

It would probably be necessary to get anti-inflammatory drugs across the blood-brain barrier. Either by developing new transport systems through the barrier or by injecting the drugs directly into the cerebrospinal fluid.

And how could neurodegeneration be stopped?

So far, there are few effective drugs available. Nevertheless, I would like to emphasize one thing. In the past, people used to say, “Yes, the tissue is degenerated – there's nothing you can do about it.” But today we know that even the adult brain remains plastic throughout life (a concept referred to as neuroplasticity) – and that still includes a brain damaged by MS. Based on such findings from basic research, we are confident that we can achieve regular and long-lasting improvements in our MS patients with chronic forms of the disease through appropriate training as part of neurorehabilitation.

Further reading

- Haider; L.: The topography of demyelination and neurodegeneration in the multiple sclerosis brain. Brain. 2016 Mar; 139(3): 807–815 URL: https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awv398 . [Full text]

First published on February 12, 2017

Last updated on July 9, 2025